“Guys, I’m rich.”

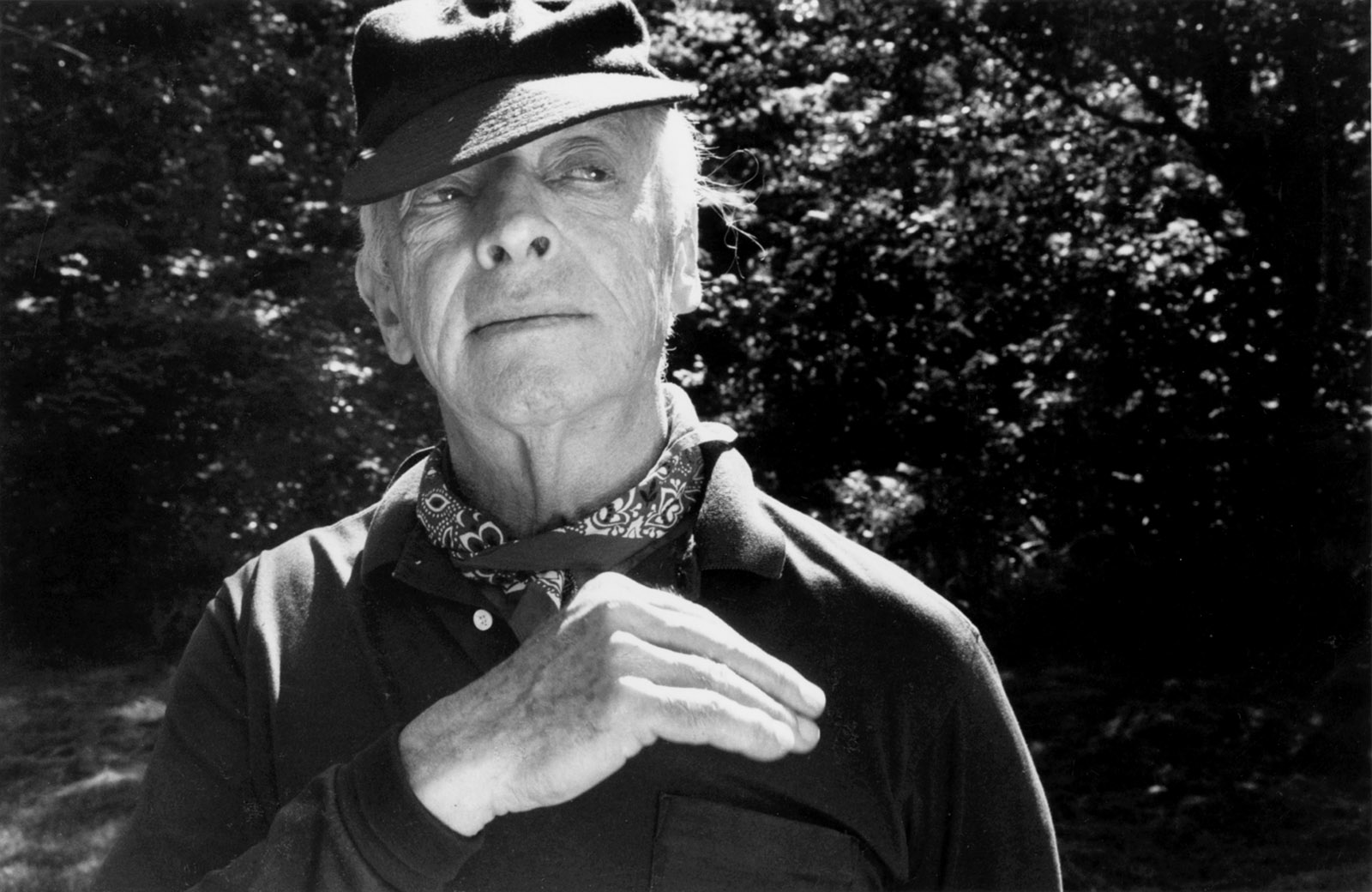

So begins the second volume of Zachary Leader’s Life of Saul Bellow, and so begins the second half of Bellow’s life. The publication of Herzog in 1964 had elevated a respected if underselling midcareer novelist to the status of publishing darling, national celebrity, golden-fingertipped literary divinity. Bellow’s income that year was the equivalent in today’s dollars of approximately $1 million. It was higher each of the next three years. He began to turn down lucrative awards and lecture fees to avoid the tax liability. “The earlier Saul had disappeared,” said his friend Mitzi McClosky, referring to the Saul who was tyrannized by his father and the financial success of his businessmen brothers, the Saul who hustled to secure time for his work amid low advances, grants, and teaching gigs, the Saul aggrieved by being pigeonholed as a “Jewish writer.” The new Saul had made it, all right. But he was no less besieged. If the great enemy of the writer was, as he often put it in speeches and essays, the “frantic distraction” that intruded on “the quiet of the soul that art demands,” that enemy now came swarming over the barricades.

It came in the form of family members hawking investment schemes in Miami real estate and Oklahoma oilfields; grifting accountants; literary agents touting stock tips; divorce lawyers (his third divorce, out of an eventual four, may have set the record for the most expensive in Illinois history); academic and literary institutions offering positions and prizes and other compensated entanglements; writers hoisting protest letters; invitations to judge the Booker Prize, the MacArthur “genius” award, and the Miss USA Beauty Pageant; and a new class of professional admirers (“career parasites,” he called them) who sought his mentorship, founded the Saul Bellow Journal, and proposed writing his biography. There were also the girlfriends, mistresses, and wives—and with them, the three sons, though these were more easily evaded (Bellow’s parental strategy, in the words of Adam Bellow, was “benign neglect until their minds had matured enough to be somewhat interesting”). But the incursion that most acutely tested Bellow came from the “great public noise”: the convulsive debates over race, war, gender, and inner-city crime that dominated American life in the decades following Herzog’s publication. Bellow reigned as the nation’s preeminent novelist during much of this time, a station that forced him, again and again, to confront the paradox that lay at the heart of his identity as a writer.

“It excites me, it distresses me to be so immersed,” wrote Bellow during this period. He was referring to a reporting trip to Jerusalem, but he might have been describing his new position in American culture: insisting on the writer’s need for independence from worldly affairs while throwing himself into them. Bellow was much closer to F. Scott Fitzgerald than Thomas Pynchon on the novelist-sociability scale. He joined boards, political committees, and neighborhood study groups. He developed an international reputation as a charmer at dinner parties; a predilection for alligator shoes, Savile Row fedoras, camel-hair overcoats, and bespoke suits in wool and shantung (“a king’s haberdashery would not have surpassed his wardrobe,” says the writer Dana Gioia, who met him in 1976 as a graduate student); and a wide, ever-growing circle of friends with whom he took pains to keep in touch.

His hostility to distraction was more figurative than literal. His working day ran from nine until noon or one, but it was not inviolable; Alexandra, his wife from Humboldt’s Gift to More Die of Heartbreak, an accomplished mathematician who required total isolation in order to work, reports with astonishment that when the phone rang, he “engaged in these very lively conversations, and then he’d go back to work with just as much energy and zest as before.” The afternoons left him plenty of time for his abundant correspondence (see Benjamin Taylor’s Saul Bellow: Letters), long walks, and his academic responsibilities, which he assumed with an enthusiasm that far outpaced financial need or professional obligation.

He taught university literature seminars for nearly his entire adult life. Between 1962 and 1993 he served on the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago, the august interdisciplinary graduate program that championed a wide reading of the fundamental works of Western thought. In 1970, at the height of his fame, he agreed to chair the committee, recruiting new appointments, quarreling with deans over bureaucratic demands, managing tensions between professors, and evaluating the academic achievements of art historians, philosophers, and political theorists—grueling, often dull work that might have cost him a novel’s worth of labor.

He came close to writing books about Hubert Humphrey and Robert Kennedy, and he wrote letters to the editor and published articles in the Chicago Sun-Times about student protests and the Johnson administration. He also attacked authors who wrote about “political campaigns, wars, assassinations, youth movements” instead of “private feelings, personal loyalties, love.” One thinks of Moses Herzog, swiveling in consecutive lines from Tolstoy (“to be free is to be released from historical limitation”) to Hegel (“the essence of human life [is] to be derived from history”). Bellow swiveled in just this way between engagement and disengagement, from jealous isolation to cocktail hour, morning to afternoon and back again.

Advertisement

If novelists have some responsibility to write about the political crises of their day, what is the appropriate register? And what form should such writing take? Bellow didn’t think highly of journalism. When Albert Corde in The Dean’s December is praised for being “a journalist of unusual talent,” he replies, “Don’t you believe it. There is no such thing. That’s just the way journalists pump, promote, gild and bedizen themselves, and build up their profession, which is basically a bad profession.” But Bellow was a dogged, deeply perceptive journalist, and for decades returned to the form when he wished to write about matters of urgent public interest. A family connection in Israel was struck by his reporting style: “He listened not only to the story, but beyond that: he listened with all his senses, to body language, to intonation, noticing all details thoroughly and in depth.”

The reported pieces in It All Adds Up, a collection of Bellow’s nonfiction reissued last year by Penguin Classics, flash with such sensual detail. A Spanish commandante in postwar Madrid, “lean, correct, compressed, and rancorous,” carries a black-market white loaf “under his arm like a swagger stick” (“Spanish Letter,” 1948); the bloated Egyptian dead in the streets of Sinai “resemble balloon figures in a parade” (“Israel: The Six-Day War,” 1967); the skyscrapers of downtown Chicago are “armored like Eisenstein’s Teutonic knights staring over the ice of no-man’s-land at Alexander Nevsky” (“Chicago: The City That Was, the City That Is,” 1983). In his nonfiction Bellow was often political. But he was rarely polemical. This got him in trouble. The more furious the political debate, the less tolerance for nuance, uncertainty, moral complexity. As his fame grew, Bellow came under increasing pressures to take a stand on the issues of the day. But he refused to be an activist, a refusal that was as artistically heroic as it was personally disastrous.

In 1965 he defied more than a dozen of the nations’ leading writers to attend a White House Festival of the Arts, after Robert Lowell had denounced the event in a letter sent to The New York Times. “Every serious artist,” wrote Lowell, “knows that he cannot enjoy public celebrations without making subtle public commitments.” Bellow disagreed. Despite publishing letters in the Times and the Chicago Sun-Times condemning the Johnson administration’s policies in Vietnam, he saw no reason to follow Lowell’s example. “The President intends, in his own way, to encourage American artists,” said Bellow. “I consider this event to be an official function, not a political occasion which demands agreement with Mr. Johnson on all policies of his administration.” He later called his decision to attend “foolish,” given the uproar, which made the possibility of a dignified ceremony impossible—an expression not so much of regret as disgust for the showmanship of the other writers.

This would be, in retrospect, a quaint prelude to the attacks Bellow would receive for To Jerusalem and Back, a portrait of Israel drawn from reportage, memoir, and, in the spirit of the Committee on Social Thought, a deep reading of philosophy, history, and literature, mixing his own observations with those of Stendhal and Sinyavsky and Sartre. “Perhaps to remain a poet in such circumstances is also to reach the heart of politics,” wrote Bellow, explaining his method. “Then human feelings, human experience, the human form and face, recover their proper place—the foreground.” He used the novelist’s devices of analogy, description, and deep questioning, always being careful to avoid the imperatives of activist writing. This enraged partisans and close observers of Israel. The Jerusalem Post attacked him for mimicking “Arab and left-wing propaganda against the State of Israel”; for Noam Chomsky, Leader writes, “Bellow’s book might have been written by the Israeli Information Ministry.” Both camps held Bellow guilty of humanizing the enemy.

“The Chicago Book,” as Bellovian scholars now refer to it, was to be a work of nonfiction in the mode of To Jerusalem and Back but was never completed. Bellow instead harvested the draft for use in lectures, essays, and The Dean’s December, in which the university dean Albert Corde invites personal and professional trouble by publishing in Harper’s two essays about the city’s criminal justice system and inner-city crime. The resentment stirred up by the articles—“Liberals found him reactionary. Conservatives called him crazy”—is the same Bellow anticipated he would receive should he publish the Chicago Book, and that he did receive when he let loose about Chicago in interviews and speeches.

Advertisement

Leader gives an agonizing account of Bellow’s two Jefferson lectures in 1977, sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Bellow delivered the second, more tendentious lecture in the Gold Coast Room of the Drake Hotel, before an audience of museum donors, university bigwigs, and arts club members. Insulting these paragons of American prosperity from the start, Bellow spoke of a feeling that “this miraculously successful country has done evil under the Sun, has spoiled and contaminated nature, waged cruel wars, failed in its obligations to its weaker citizens.” The audience also failed to be charmed by Bellow’s insinuation that wealthy Chicagoans were complicit in their city’s deterioration, immured in their Lake Shore Drive high-rises, in “strange isolation” from the reality of the streets below or, worse, had escaped to the suburbs, from which wafted the “dank and depressing odors of cultural mildew.” The hometown Nobel laureate was greeted with “muted applause” and largely ignored at the cocktail reception.

The response was not quite as decorous from students and faculty (“Bellow: False and Racist?” was the title of a protest letter in The Chicago Maroon, the University of Chicago student paper), who were shocked by Bellow’s depiction of neighborhoods that in his youth were inhabited by immigrants who “improved themselves and moved upward” and that now he described as dystopic, third-world, savage. In the inner-city schools, “76 percent black and Puerto Rican,” the children “are like little Kaspar Hausers—blank, unformed, they live convulsively, in turbulence and darkness of mind…. But they are unlike poor innocent Kaspar in that they have a demonic knowledge of sexual acts, guns, drugs, and of vices, which are not vices here.” A similar uproar followed the publication of The Dean’s December. It did not help that Bellow, in his defense, explained that he was speaking up “for the black underclass and telling the whites they’re not approaching the problem correctly.” A novel intended as a protest against “the dehumanization of the blacks in big cities” furthered the dehumanization.

Leader points out that racial injustice had been a dominant theme for Bellow since the beginning of his career. In the fragment “Acatla” (1940), an interracial couple is victimized by prejudice, and Bellow’s first completed novel, The Very Dark Trees (1942), was about a white man who wakes up black (after selling it to a publisher Bellow threw the only copy into a furnace). In essays written in the 1950s Bellow attacked depictions of black primitivism, later espoused most flagrantly by Norman Mailer in “The White Negro,” as dangerous, provoking “envious rage and murder,” and he supported the Congress of Racial Equality, for which he wrote the preface to a book to be titled “They Shall Overcome.” The essay attacked the rural white poor, whom he held responsible for much of the nation’s racial animosity and violence. “Rural America has had a long history of overvaluation,” he wrote, thanks to the mistaken notion that

everyone was better and sounder on the farm, in the woods and hills, less anomic, more self-reliant, fairer, more American. This is simply not so. In provincial America, North no less than South, lives the most unhappy, troubled and alienated portion of the population….The glamor of Confederacy and insurrection, of “tradition” and “gentility” has been laid in poster colors over provincial pride, backwardness, xenophobia and rage.

Such bona fides would win Bellow no public mercy, however, and his political statements brought increasing scorn in his final decades. What Adam Bellow called his “irreverent attitude toward reigning intellectual authorities” had been responsible for his singular voice—vernacular scrambled with elevated, crude with transcendent, Humboldt Park with Hyde Park. Carried into the political sphere, the same impulse translated into a lifelong aversion to ideological factions, with their enforced orthodoxies, slogans, and public mantras—any group in which “the emphasis falls on collective experience and not upon individual vision.” He would lecture his sons: “Don’t disappoint me, don’t be one of those people who just line up.” Bellow’s antipathy to just lining up derived from his view of what literature should be, and by extension, how artists should direct their energies, and it tended to overwhelm any political beliefs he held.

Broadly speaking, he was a young Trotskyite who migrated, in stages, to a fuddy-duddy conservativism. But even the slightest scrutiny revealed inconsistencies that would alienate any natural ally—what he called his “obstinacy to mark my disagreement with all parties,” and what Leader sees, more decorously, as a compulsion “to wound, to force his listeners and readers to face what they have chosen not to face.” The force of Bellow’s opposition to the Vietnam War and US nuclear policy was matched by his opposition to the civil disobedience of their youthful protesters. If Bellow was so antiwar, an earlier biographer wondered, “why then was he embattled with anti-war people when they met?” Bellow voted for Adlai Stevenson but hated “Stevenson people,” which Leader translates as “liberals interested in political personalities and electoral politics.” He ridiculed women’s liberationists and hippies but supported George McGovern against Richard Nixon in 1972. In the 1970s and 1980s he joined a series of conservative foreign policy groups, only to resign from each in turn when they issued statements in his name with which he vehemently disagreed.

His reputation as a conservative grew after a 1988 New York Times Magazine profile of his friend Allan Bloom, which quoted Bellow’s remarks mocking a student movement at Stanford to cancel a Western civilization class on the grounds that it was racist, remarks that to this day haunt his ghost: “Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus? The Proust of the Papuans? I’d be glad to read them.” When he was asked by a Washington Post interviewer about his unflattering portrayal of a female character in his story “What Kind of Day Did You Have?,” a woman who is “old-fashioned and sexually enslaved without a mind of her own,” Bellow responded, “Well, I’m sorry girls—but many of you are like that, very much so. It’s going to take a lot more than a few books by Germaine Greer or whatshername Betty Friedan to root out completely the Sleeping Beauty syndrome.” Bellow nevertheless considered himself “some sort of liberal,” despite his distaste for the left’s “taboo on open discussion.”

He violated a major taboo on the right, however, when he suggested in Ravelstein (2000), his fictionalized eulogy for Bloom, that his late friend was a homosexual who had died of AIDS. Bloom’s friends had known of his homosexuality but kept it private out of fear that the revelation would destroy his reputation in conservative circles. “They see themselves as having a special pious duty to protect Bloom,” Bellow told the Times, once again forced to defend himself. “I can understand that, because for them it’s not just a friend, it’s a movement.” The piece was titled “With Friends Like Saul Bellow” and illustrated with an image of a dagger; a Wall Street Journal article about the controversy was accompanied by a drawing of a man being stabbed in the back.

“I couldn’t be both truthful and camouflaged.” Bellow meant true to the requirements of fiction, which demands that any believable character must be full of contradictions, secrets, regrets. For Ravelstein to succeed as fiction, it required “the elasticity provided by sin.” Absent disclosure of Bloom’s secret life, the character would be false—a two-dimensional public figure instead of the private person, who was the only one worth writing a novel about.

There were two kinds of writers, Bellow said in a 1975 interview: “great-public writers” and “small-public writers.” The second category was typified by the modernists, who emphasized stylistic artistry over social protest: Flaubert, Joyce, and Baudelaire. The great-public writers, who had largely fallen out of fashion, “thought of themselves as spokesmen for a national conscience. They addressed grand issues of social justice and political concern.” He cited as examples Dreiser, Dickens, Zola, Upton Sinclair, and Sherwood Anderson—and himself. Bellow did not, in the interview, acknowledge that he had started out as a small-public writer. Dangling Man, The Victim, The Adventures of Augie March, Seize the Day, and Henderson the Rain King, though wildly divergent in sensibility and plot, shared a narrative emphasis on the forging of an identity and, for Bellow himself, the forging of a personal style. Later in life he regretted, as the narrator of The Bellarosa Connection (1989) puts it, “snoozing through” the Holocaust. But he went great-public with Herzog for good; like the Romantic scholar Moses Herzog, Bellow became the author of a “new sort of history…personal, engagée.” In the later novels, Bellow achieved what he could not do in his essays, speeches, and reportage: he allowed the great public noise of his age into the innermost reaches of his characters’ thoughts and feelings. He made the public personal.

These novels perform a double trick. They dramatize Bellow’s own struggle to connect the outer world with his inner world; and, in so doing, they provide a model for how to pursue what Charlie Citrine and Artur Sammler call “higher consciousness” without fleeing society and joining a monastery. “The practical questions have thus become the ultimate questions,” says Moses Herzog. “To live in an inspired condition, to know truth, to be free, to love another, to consummate existence…is not reserved for gods, kings, poets, priests, shrines, but belongs to mankind and to all of existence.” The path to enlightenment lies not in renouncing the world but in seeing it more clearly.

So we get Sammler emerging at night onto Riverside Drive, its urine-soaked phone booths lit bright by the streetlamps: “All metaphysicians please note. Here is how it is. You will never see more clearly. And what do you make of it?” Citrine seeking transcendence in daily ephemera: “Often I sat at the end of the day remembering everything that had happened, in minute detail.” And Albert Corde throwing himself headlong, heedlessly, into a painful scrutiny of the Chicago Criminal Courts Building and Cabrini Green: as long as “the spirit of the time” doesn’t “come to us with some kind of reality, as facts of experience, then all we can have instead of good and evil is…well, concepts. Then we’ll never learn how the soul is worked on.”

Edward Shils, a don of the Committee on Social Thought with whom Bellow fell out late in their lives, condemned Bellow’s refusal to “take sides.” A “great novelist,” groused Shils, “has to have some moral sense. That has been Bellow’s blind spot.” Shils cited Bellow’s “self-indulgent” characters and Bellow’s own self-indulgence, “as he floated from one woman to the other.” Leader is unstinting on Bellow’s personal moral failings—the infidelities and cruelties to the women who loved him, the high-handedness with close friends who asked for favors, professional underlings (his agents nicknamed him “God”), and his sons. But the novels themselves do articulate a consistent moral vision. They reveal how the soul is worked on by an age of radical social upheaval—and how the soul must respond.