In 1694 a young Scotsman convicted of murder in London fled to the Continent. Two decades later he turned up in Paris, where he founded a national bank and headed a company that incorporated all of France’s overseas trading monopolies and absorbed the country’s entire national debt. The bank’s new paper notes replaced the old currency of gold and silver. The company’s stock soared extravagantly in value. The erstwhile fugitive was appointed finance minister, becoming the most powerful subject in Europe and possibly the richest man who ever lived. Daniel Defoe, a sharp observer of stock promoters (or “projectors,” as they were commonly known), expressed incredulity: in order to rise in this world,

the Case is plain, you must put on a Sword, Kill a Beau or two, get into Newgate [jail], be condemned to be hanged, break Prison, if you can,—remember that by the Way,—get over to some Strange Country, turn Stock-Jobber, set up a Mississippi Stock, bubble a Nation, and you may soon be a great Man….

Yet by the time these words were published in early 1720, the bubble was on the verge of collapse. Not long after, its creator found himself once again in exile and nearly bankrupt.

For nearly three centuries John Law, who was born in 1671 and died in 1729, has eluded biographers. The distinguished American economic historian Earl J. Hamilton reportedly spent fifty years working on a life but produced only a few papers on the Mississippi bubble. The editor of Law’s collected works, Paul Harsin, also promised and failed to deliver a scholarly biography. There have been several popular biographies—most recently Janet Gleeson’s The Moneymaker (1999)—that are rollicking reads, but all suffer from a tendency to conflate fact with legend.

The Irish historian of economic thought Antoin E. Murphy produced a detailed academic analysis of Law’s ideas and career in his biography, John Law: Economic Theorist and Policy-Maker (1997), but gave little sense of Law’s character or the times in which he lived. For years the most thorough and accessible account of this elusive Scotsman had been La Banqueroute de Law (1977) by the French politician and essayist Edgar Faure. James Buchan’s John Law: A Scottish Adventurer of the Eighteenth Century is the first English-language biography that is comprehensive, scholarly, and also readable.

One can see why the wait was so long. Little is known of Law’s early life or of his rakish sojourn in London, which ended with the young Law, then known as “Jessamy John,” killing another dandy, “Beau” Wilson, in a duel that took place in mysterious circumstances in April 1694. Law was sentenced to death but escaped from jail with help from high-placed friends. Details of his subsequent peregrination across Europe, with sojourns in The Hague and Genoa, are also sketchy. According to Buchan, Law vanished without trace between 1695 and 1700, and again in the early 1720s.

Law’s Continental life requires of any biographer a grasp of several European languages, including French, Italian, German, and Dutch. Buchan, who knows them all, did research in some thirty archives across Europe, from Genoa to Edinburgh. He does not always bear his learning lightly. At one point, Buchan states that Law could not possibly have attended Edinburgh High School, a top grammar school, on the grounds that “in his writings in French, Law makes small mistakes that he would not have made had he known the Latin grammar underlying the language.” This overconfident assertion reveals more about the author’s own erudition than it does about Law’s education.

There are several minor revelations about his life. Law appears to have earned money in Genoa victualing British troops in Catalonia during the War of the Spanish Succession. Buchan also reveals the Scotsman’s close relations with the exiled Stuart court of the Old Pretender (or James III, as Buchan styles him), whom Law supplied with money. More importantly, Buchan’s archival research provides a richness to Law’s life that is lacking in earlier biographies. He has a novelist’s eye for curious details, from the heraldic devices decorating the doors of the coach in which the British ambassador Lord Stair entered Paris to the music played at a ballet lesson of Law’s son, William, in preparation for a performance with Louis XV, the boy king.

Law was an economic visionary with a novel idea of money. The conventional view in his day, and for long afterward, was that the value of money derived from the precious metals, commonly gold, silver, or copper, from which it was fashioned. John Locke’s advice in the 1690s on the English currency stated that “silver is the instrument of commerce by its intrinsic value.” Law dismissed such notions. Silver, said Law, received much of its value from its use as money. As for money, it was merely an abstract yardstick intended to measure the value of other things. As Law expressed it in his 1705 tract, “Money and Trade Consider’d”: “Money is not the value for which goods are exchanged, but the value by which they are exchanged.” Law’s clever switching of the prepositions amounted to a monetary revolution. Once it was recognized that money held no intrinsic value, it followed that the coinage no longer needed to be backed with precious metals. This opened up the possibility of manipulating the money supply and interest rates in order to boost trade.

Advertisement

Law’s financial ideas were not entirely original. As Defoe pointed out, any stock-jobber at the time knew that paper credit could be used as money. The young Law would have learned as much from his father, a goldsmith who was also a banker to the Scottish nobility. Law’s proposal in “Money and Trade” for a land bank—which would issue notes backed by property collateral—was similar to a number of other land bank schemes, the first of which dated to the time of Cromwell’s Protectorate. Law’s plan for a national bank whose capital would be supplied by investors exchanging government debt for bank shares was modeled on the Bank of England (established in 1694) and on the South Sea Company (founded in 1711). Law was also influenced by Genoa’s Bank of Saint George, where he maintained an account and which in the early fifteenth century had sold the city’s public debt in exchange for dividend-paying shares. Law’s Mississippi Company and Royal Bank were not short of precedents.

Still, as Joseph Schumpeter wrote, Law “worked out the economics of his projects with a brilliance, and, yes, profundity, which places him in the front ranks of monetary theorists of all times.” His true genius lay in absorbing the ideas of the age and having the boldness to put them into practice. In the 1920s, Keynes would still be railing against gold-backed currency—yet for a few months in early 1720 Law succeeded in banishing that “barbourous relic” from France. By doing so, he anticipated the demonetization of gold that followed the collapse in 1971 of the Bretton Woods currency system, which had required participating countries to partially back their currency with gold.

Law was fortunate that France had come under the rule of the open-minded and easy-going regent Philippe d’Orleans, who was prepared to try anything to restore the nation’s finances, which had been ruined by the Sun King’s endless wars. In 1716 Law was granted permission to open France’s first joint-stock bank, known as the General Bank. A few years later this institution was transformed into the country’s first central bank, whereupon it was renamed the Royal Bank.

In 1717 Law founded the Company of the West to acquire the land and trading rights to Louisiana, a territory then comprising around half the landmass of the contiguous United States. Soon after, the Company of the West merged with France’s other overseas trading companies—the Senegal Company, whose main trade was in gum arabic and slave labor for the American plantations, along with the East India Company and the China Company—and was renamed the Company of the Indies, although it was known popularly as the Mississippi Company. The company also acquired the rights to France’s tobacco monopoly, the Royal Mint, and collection of taxes; and finally, in exchange for an annual cash payment, it took over all of the French king’s debts, a sum roughly equivalent to the country’s annual national income.

Law needed a high share price in order to persuade the holders of government debt to exchange their securities for company stock. He employed a variety of tricks to this end. At one stage, Law personally offered to buy large numbers of shares of the company at a higher price than the market rate (in financial terminology, he was buying call options). He made a large public bet with Lord Londonderry that the Mississippi Company’s shares would outperform those of the English East India Company (this wager eventually cost Law much money and trouble).

As more shares were issued, down payments were lowered—only 5 percent of the total price of a share was required for those issued in July 1719. To be eligible to subscribe, investors were required to hold shares from earlier issues—the first generation of shares were known as mères, followed by the filles and petites-filles. Law increased the dividends paid by the company (it is arguable whether these payments were covered by profits) while simultaneously bringing down interest rates. His intention was to make the shares appear a more attractive investment than government securities.

Advertisement

More than by any of these measures, the bubble was inflated by Law’s banking operations. When the General Bank was nationalized in late 1718, it had around 40 million livres of notes in circulation and the company’s share price was trading below 500 livres. By the following summer, ten times as many notes circulated and the share price had doubled. The newly printed banknotes were loaned to speculators to buy shares. The company also borrowed to buy back its own shares—toward the end of 1719, Law opened a bureau d’achat et de vente for this purpose. The bank’s note issue at the time approached one billion livres, and the share price was close to 10,000 livres: a twenty-fold increase in a year. To put that in perspective, this stratospheric price rise exceeds that of bitcoin during its heady 2017 climb. Whereas the peak value of the total amount of bitcoin surpassed that of the Toyota Motor Corporation, by January 1720 the Mississippi Company was worth twice France’s GDP. By comparison, Buchan says, “Apple Inc is a rag-and-bone shop.”

The social and political background to the Mississippi saga is particularly well handled by Buchan, whose deep understanding of this aristocratic age is displayed through a quite remarkable ability to place almost every one of the numerous characters who appear in the narrative. If the book has a hero, aside from Law, it is the Duc de Saint-Simon, the gossipy courtier (and ally of the regent) upon whose memoirs Buchan copiously draws. Buchan shares Saint-Simon’s obsession with social rank. As a result, he is able to convey the interconnectedness of the upper strata of European life, which transcended national borders and even religious denomination.

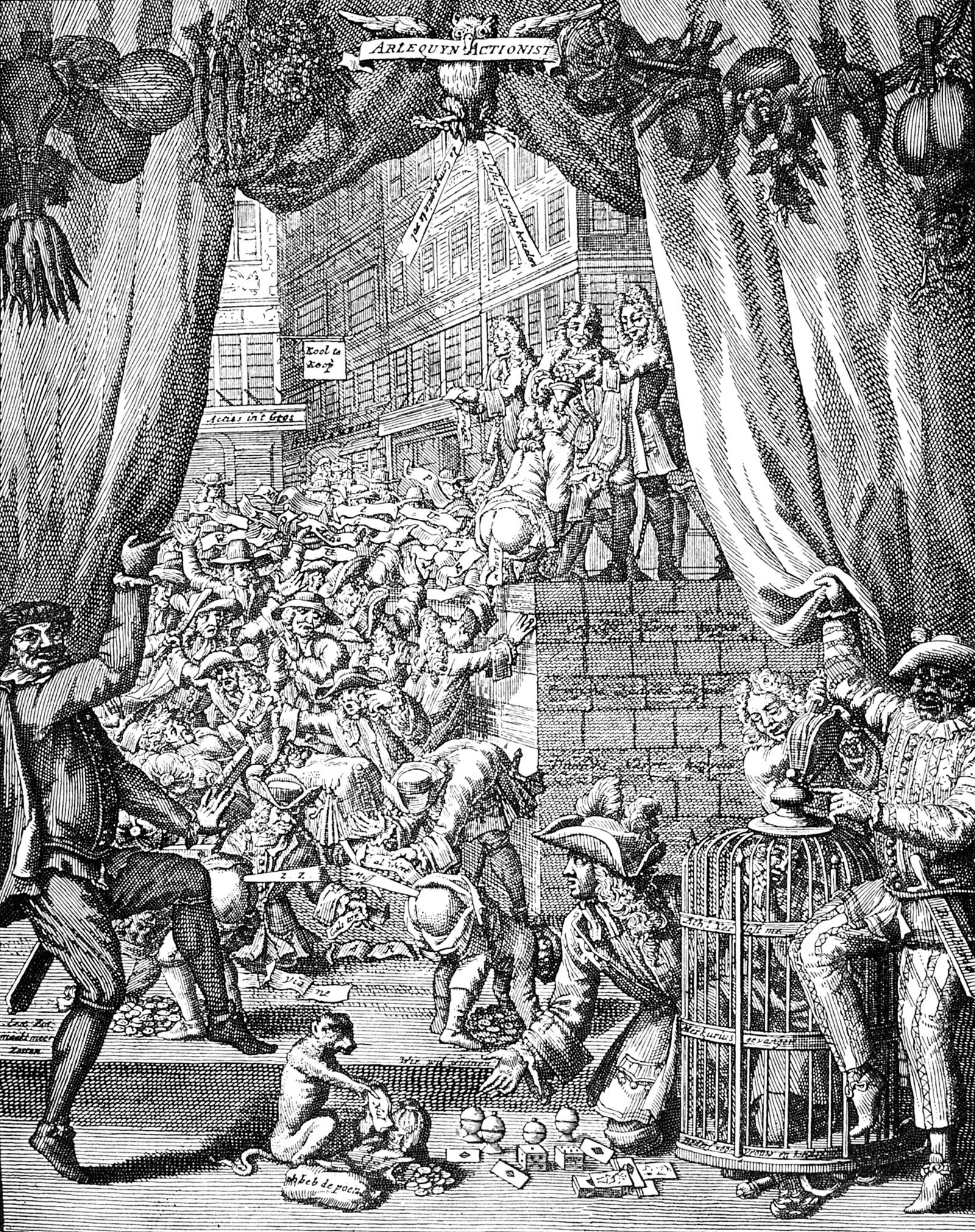

It is clear from this account that Law’s initial success was due to the support, assiduously cultivated, of the aristocratic elite whose members were among the most ardent Mississippi speculators. The real mania was not the trading of shares in the stock market in the rue Quincampoix (later moved to the Place Vendôme and then to the Hôtel de Soissons) but in the frenzied struggle for access to Law’s person, since it was he who controlled the distribution of shares. There were numerous stories, both true and false, of people debasing themselves to gain the great man’s favor. As the regent’s mother, Elisabeth Charlotte, dowager duchess of Orleans, known at court as Madame, wrote in a letter to the Princess of Wales, if duchesses were prepared to kiss Law’s hand, what parts must other ladies have to kiss? In a subsequent letter, Madame was more explicit: “If Mr Law so desired, the French ladies would be happy to kiss—pardon my French—his arse.”

The Mississippi scheme earned political support because its effect was to transfer wealth from rentiers—the holders of government annuities, of which the largest group were religious houses—to speculators, many of them of noble birth. Law’s project began to fail when the great nobles, among them the Duc de Bourbon, started to realize (one of the era’s neologisms, along with the word millionaire) their profits, thereby reversing Law’s alchemy of turning gold into paper. It is no coincidence that the greatest architectural legacy of the bubble, in Buchan’s view, are the stables of Chantilly, the Grandes Écuries, which were built by the Duc de Bourbon with his Mississippi profits and once housed more than two hundred horses and twenty-three coaches. Law vainly attempted to stop speculators from cashing out and taking their profits abroad but only succeeded in antagonizing his former supporters.

Historians often depict Law’s system as a failed attempt to introduce the techniques of what was called “Dutch finance”—which in Holland and England comprised credit money, a government debt funded with taxes and supported by a national bank, and joint-stock companies whose shares were traded on the stock exchange—into ancien régime France, with its rickety revenues derived from farming out the collection of taxes and selling public offices and expensive annuities. The bubble’s collapse left the French with a lasting distrust of modern finance, putting the country at a disadvantage with its great rival England, whose government was able to borrow at lower cost throughout the eighteenth century.

It was clear to several contemporaries, including Saint-Simon, that Law’s efforts were doomed from the start. Credit and all the other trappings of modern finance require trust, which in turn depends on freedom from arbitrary state intervention. France’s monarchy, unlike England’s after the Glorious Revolution, remained absolute. Law’s mistake was to use these absolutist powers to force his system upon the nation. On several occasions he altered by decree the value of gold and silver to make his banknotes more attractive, and when things started falling apart in early 1720, he went so far as to ban the possession of precious metals. In the end, Law’s tyrannical, and at times whimsical, measures undermined confidence in his paper currency. The Mississippi Company was only ever a “brat of the state,” said Defoe, adding famously that although Law might have paid off the French king’s debts, it was preferable to be “a free nation deep in debt rather than a nation of slaves owing nothing.”

Law’s character also vitiated his chances of success. He was undoubtedly a man of immense charm. Several accounts suggest that even at the height of his greatness, his head was not turned by fame or fortune. But he was an inveterate gambler, always restless and often reckless. According to Buchan, Law “hated to delegate and then, when he did so, employed desperadoes,” such as the brutish Edouard de Rigby, who had been cashiered from the Royal Navy for buggery and was put in charge of managing the Louisiana trade. Despite having a brilliant head for figures (to which he owed his gambling fortune), Law paid little attention to the management of what was, in market value and economic reach, the largest corporation in history. The huge vessels ordered by the company at top price from British shipyards were hastily constructed and sailed badly.

Buchan quotes an insightful comment by a Lyonnais official, Laurent Dugas, to a cousin who in the summer of 1719 was considering an investment in the company:

Whatever Mr. Law’s genius, it was impossible for a single intellect to be strong enough to conduct a trade that embraces both East and West where every part requires infinite pains and limitless foresight…. For the project to succeed, its author would have to be immortal and for ever sure of enjoying the same confidence of his prince.

After his departure Law made an extraordinary confession in a letter to the regent that he had “always hated work.” Besides, his patron’s support was only ever provisional.

The frail monetary foundations of the system proved Law’s undoing. Owing to the bank’s extravagant printing of banknotes in 1719, France’s money supply doubled. As a result, commodity prices started to soar and the currency collapsed on the foreign exchanges. By early 1720, Law faced a dilemma: he could either continue printing money to maintain the company’s share price and risk galloping inflation and a currency crisis, or he could withdraw the excess of notes from circulation, thereby deflating the bubble. In the end, Law chose the second option. As the bubble burst—the Mississippi stock lost around 80 percent of its value between May and December—riots broke out in Paris and Law’s carriage was smashed to pieces by the mob.

In early 1721, less than a year after being appointed controller-general of finance—in effect, prime minister of France—Law was in exile, traveling under an assumed name across Germany, separated forever from his wife and daughter and fortune (he took his son William with him). He eventually washed up in Venice, paying his way by gambling but with less success than in the past, hoping that the French monarch would restore some of his wealth, plagued by lawsuits, and a curiosity to visitors such as Montesquieu, whose verdict was that Law had been more in love with his ideas than with money. In February 1729, after dining with the British minister resident during Carnival, Law caught pneumonia. He died the following month, aged fifty-seven.

Buchan, a former Financial Times journalist, has no trouble keeping track of the complexities of Law’s financial arrangements. Yet although he is the author of an earlier treatise on money, Frozen Desire (1997), Buchan has little interest in analyzing the economic flaws of Law’s system. This is a pity, since there are lessons here for the current day. As Antoin Murphy recently suggested, Law can be seen as the father of modern central banking.1 The policy of quantitative easing pursued by the Federal Reserve in the aftermath of the global financial crisis—which involved acquiring US treasuries and other securities using newly created money—was first elaborated in theory and put into practice by Law in Regency France.

Law was an advocate of low interest rates, which he believed would help revive the French economy. His system succeeded in reducing the cost of government borrowing from about 8 percent during the reign of Louis XIV to 2 percent by 1720. In recent years, the Federal Reserve has pushed interest rates even lower. One of the consequences of depressing interest rates has been an inflation of asset price bubbles, from the unicorns of Silicon Valley to apartments in Manhattan. The US stock market is today more expensive, valued on its dividend yield, than the Mississippi Company at its peak (dividends for the Mississippi Company were 2 percent in 1719; the S&P 500 Index currently yields around 1.8 percent).

Buchan signals his lack of interest in the economics of Law’s system when he makes an offhand reference to the Irish-born Parisian banker Richard Cantillon, whom he describes as a person who “went on to write a work of political economy.” This is a gross understatement. Cantillon’s Essai sur la Nature de Commerce en Général is widely considered the first great systematic work of economics.2 Cantillon was a partner of Law’s in the Louisiana settlement but later had his doubts about the system and speculated against the French currency on the foreign exchanges. His Essai, written in the late 1720s, still provides the best critique of Law’s monetary experiment.

In the short term, Cantillon concluded, a national bank could force interest rates down by printing banknotes to purchase government bonds. But such operations were dangerous. The economy would prosper only as long as the extra banknotes were kept within the financial system, not used “for household debts” or “changed for silver.” Once those excess notes escaped into the economy at large, inflation would break out. Cantillon identified another problem. It was all very well for a national bank to buy debt securities in a rising market. But to whom would it sell them in a falling one? “If the Bank alone raises the price of the public stock by buying it, it will be so much depressed when it resells to cancel its excess issue of notes.”

After a decade of monetary easing following the subprime crisis, central bankers today find themselves in a similar position to Law in the spring of 1720. They can choose to keep interest rates low and continue taking on debt. Such a policy would probably maintain asset prices at an elevated level, but at some stage old-fashioned inflation is likely to return with a vengeance. Or they can reverse course. The Federal Reserve has already taken tentative steps toward this end by raising short-term rates and reducing its debt (what’s known as “quantitative tightening”). Law’s failure to withdraw the excess banknotes without collapsing the bubble suggests that this latest attempt to escape from a bold monetary experiment could prove difficult.

Buchan can be forgiven for not dwelling on such dismal concerns. He has produced the most complete account of Law’s turbulent career and times. This work adds to, rather than competes with, Murphy’s earlier analytical biography. It is a further bonus that Buchan writes so elegantly. As the three hundredth anniversary of the Mississippi Bubble approaches, John Law, the greatest projector of what Defoe called a “projecting age,” finally has the life he deserves.

-

1

Atoin E. Murphy, “John Law: A Twenty-First Century Banker in the Eighteenth Century,” speech to the Fondazione Banco di Napoli, June 2017. ↩

-

2

Cantillon introduced the word “entrepreneur” into economics, outlined how imbalances in trade affected domestic prices through international movements of bullion (an idea that David Hume later borrowed without attribution), and showed how an increase in the circulation of money affected some parts of the economy before others (what is still known as the “Cantillon effect”). ↩