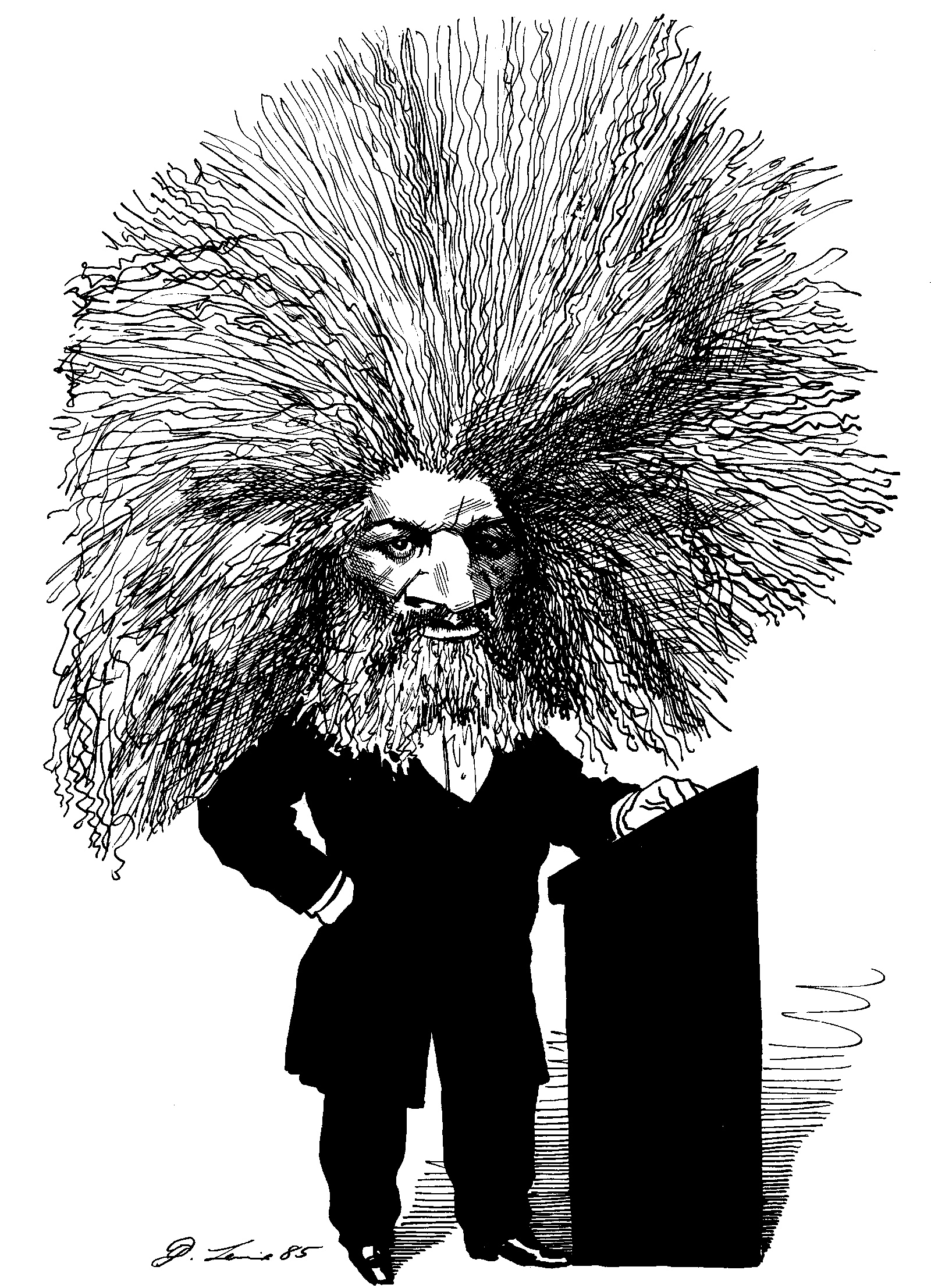

Were the Founding Fathers responsible for American slavery? William Lloyd Garrison, the celebrated abolitionist, certainly thought so. In an uncompromising address in Framingham, Massachusetts, on July 4, 1854, Garrison denounced the hypocrisy of a nation that declared that “all men are created equal” while holding nearly four million African-Americans in bondage. The US Constitution was hopelessly implicated in this terrible crime, Garrison claimed: it kept free states like Massachusetts in a union with slave states like South Carolina, and it increased the influence of slave states in the House of Representatives and the Electoral College by counting enslaved people as three fifths of a human being. When Garrison finished excoriating the Founders, he pulled a copy of the Constitution from his pocket, branded it “a covenant with death and an agreement with hell,” and set it on fire.

Garrison was one of the most unpopular men in nineteenth-century America, and this performance did little to improve his standing with the moderates of his time. Today’s historians are more sympathetic to his argument that the Constitution made possible the expansion of slavery in the early United States. According to Ibram X. Kendi, author of the National Book Award–winning Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (2016), the Constitution “enshrined the power of slaveholders and racist ideas in the nation’s founding document.” David Waldstreicher, in Slavery’s Constitution (2009), charges that the Founders produced “a proslavery constitution, in intention and effect.”

Their bleak assessments are grounded in the many protections for slaveholding agreed on at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Beyond the three-fifths rule, the international slave trade was exempted from regulation by the federal government, which otherwise oversaw foreign commerce. Congress was banned from abolishing the trade until 1808 at the earliest. The federal government was prevented from introducing a head tax on slaves, and free states were forbidden from harboring runaways from slave states. The Founders obliged Congress to “suppress insurrections,” committing the national government to put down slave rebellions. The abolitionist Wendell Phillips, an associate of Garrison’s, summarized the work of the Founders in 1845: “Willingly, with deliberate purpose, our fathers bartered honesty for gain, and became partners with tyrants, that they might share in the profits of their tyranny.”

The effectiveness of constitutional protections for slavery can be measured in the growth of the institution between the formation of the federal government in 1789 and the secession of South Carolina in 1860. Across these seven decades, the number of enslaved people in the United States increased from 700,000 to four million. The dispossession of Native Americans and the violent seizure of northern Mexico created a vast cotton belt that stretched from the Atlantic to the Rio Grande. Although Congress opted to abolish the international slave trade at the earliest opportunity in 1808, a vast domestic trade—expressly permitted by the Constitution—relocated more than a million enslaved people from upper southern states like Maryland and Virginia to the cotton fields of the Deep South. Unspeakable crimes were committed against African-Americans; countless lives were broken or ended. While individual slaveholders bore their share of responsibility, the Constitution allowed proslavery forces to use the power of the federal government to support appalling measures. With the Dred Scott decision of 1857, which denied the possibility of black citizenship in America and invited slaveholders to take their property into any state of the Union, slavery’s domination of national politics seemed absolute.

Sean Wilentz’s No Property in Man concedes the horrors of slavery and acknowledges that the Constitution benefited slaveholders. For Wilentz, though, fixating on the Constitution’s proslavery effects or racist underpinning overlooks a “crucial subtlety” at the heart of the 1787 Constitutional Convention: while the delegates in Philadelphia encouraged and rewarded slaveholders, they refused to validate the principle of “property in man.”

Most books about the Constitution, even the ones that largely ignore slavery, acknowledge that the Convention walked a difficult line on the question. By 1787, in five of the original thirteen states, the legislature had outlawed slavery or the state supreme court had ended it. Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Connecticut had passed gradual emancipation bills, which ensured that slavery in those states would survive into the nineteenth century. In New Hampshire and Massachusetts, legal challenges under the new state constitutions brought slavery to a sudden end. New York and New Jersey had already started debating emancipation before the Constitutional Convention. They finally opted for their own gradual schemes in 1799 and 1804, respectively.

Economic and demographic developments encouraged the view that slavery was in retreat in the 1780s. In Virginia, which had more slaves than any other state throughout the antebellum period, soil exhaustion and trade disruption persuaded many white planters to shift from tobacco to less labor-intensive wheat farming. Virginia’s legislators made it easier for individual slaveholders to manumit their slaves. Throughout the upper South, writers and activists disputed the idea that the region’s future depended on the perpetuation of slavery. The holdouts in this fragile antislavery moment were the Deep South states, principally Georgia and South Carolina. Even here, white voices were raised against slavery, but the political elite was deeply committed to the persistence of human bondage. “If it is debated, whether their slaves are their property,” one South Carolina politician had warned the Continental Congress in 1776, “there is an end of the confederation.”

Advertisement

If eleven of the thirteen states were antislavery or skeptical about slavery’s future, why were Georgia and South Carolina given so much leeway in the Constitutional Convention? Wilentz offers a familiar answer: had any plan for emancipation been discussed, “the slaveholding states, above all the Lower South, would have never ratified such a Constitution.” There’s a comforting finality about the logic of this: the delegates at Philadelphia did the best they could, but it was simply impossible to craft a strong central government in 1787 without sweeping concessions to slavery.

Wilentz’s book has little to say about two questions that would illuminate what is often called the “paradox of liberty”: Were threats of disunion from South Carolina and Georgia credible? And might the Virginia delegation, under the enlightened leadership of James Madison, have led the upper South (and the nation) toward a happier future? Instead Wilentz focuses on the ways in which the Deep South delegates, occasionally (but not always) supported by their fellow slaveholders in the upper South, were frustrated in their efforts to obtain an even more proslavery Constitution. Rather than viewing the Philadelphia delegates as pusillanimous on the slavery question, Wilentz sees them playing a long game: by consciously and doggedly affirming “no property in man,” the Founders insisted that freedom, rather than slavery, was the principle at the core of the new nation.

Wilentz admits there are problems with this argument. It’s easy to understand why historians believe that slaveholding interests triumphed at Philadelphia, “because in several respects they did.” He does not dispute that slavery emerged intact from the 1787 Convention, but insists that “the Constitution’s proslavery features appear substantial but incomplete.” There is a surreal quality to some of his counterfactuals in this respect. (What if the Deep South had forced the delegates to pass a five-fifths rule?)

But for the most part he looks to later developments. The exclusion of “property in man” became “the Achilles’ heel of proslavery politics.” It offered a critical opening to subsequent generations of antislavery campaigners and politicians, who could—and eventually did—point to the absence of absolute constitutional guarantees of slavery’s legitimacy. Most notably, Wilentz suggests that the Republican Party of the 1850s used the Constitution as “the means to hasten slavery’s demise.” By declining to make an explicit declaration in 1787 that slavery was a foundational principle of the United States, the Founders had brilliantly facilitated the later Republican cry of “Freedom National, Slavery Sectional.”

Our view about whether the Constitution hastened abolition may depend on how we understand slavery’s effects in the seventy-five years between the Constitutional Convention and the Emancipation Proclamation. As Calvin Schermerhorn argues in Unrequited Toil (2018), his recent book on the development of slavery in the United States, the expansion of the institution under the provisions of the Constitution did incalculable damage to African-Americans, while hugely increasing the wealth of white people. By 1860, enslaved people counted for nearly 20 percent of national wealth and produced nearly 60 percent of the nation’s exports. Historians and economists debate the centrality of slavery to the emergence of modern American capitalism, but few dispute that the gains of slavery—through shipping, banking, insurance, and commerce—were distributed nationally.

Wilentz writes that the exclusion of an explicit guarantee of property in man was not just an accident or “technicality” at the Constitutional Convention. The delegates “insisted” on it, he claims, and he offers a line from James Madison to prove his point: it would be wrong “to admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men.” This quotation is so perfect for Wilentz’s argument that he could not have invented better evidence in support of it.

But there is some doubt as to whether Madison actually used those words in Philadelphia. The debates at the Convention were held in secret, and the only person who kept substantial notes on what had been said was Madison himself. The legal historian Mary Sarah Bilder won the Bancroft Prize in 2016 for Madison’s Hand: Revising the Constitutional Convention, a brilliant study of just how extensively Madison reshaped the story of what happened at Philadelphia over his long lifetime. On the subject of slavery, she believes that Madison tinkered with the transcript of 1787 to make himself seem more righteous than he actually had been; she suspects that the specific reference to “property in men” was added at a later date. This doesn’t destroy Wilentz’s argument that “no property in man” was a discrete principle with political power, especially in the nineteenth century. But the notion that Madison and his colleagues planted antislavery language in the Constitution for Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass to discover in the 1850s is more exciting than convincing.

Advertisement

Madison is a tantalizing figure for Wilentz. The disputed quotation decrying “property in men” appears half a dozen times in his book, with Bilder’s qualms relegated to an endnote. Wilentz explains sympathetically that when Madison declared during the Virginia ratification debates that the Constitution provides strong protection for slavery via the fugitive slave clause, the Founder was “stuck in a dilemma that made candor impossible.” When evidence of antislavery intent dries up, Wilentz tells us that Madison was taking an influential stand against property in man even if he “could not or would not admit [it], not even, perhaps, to himself.”

Madison failed to free any of his slaves during his lifetime, supported the extension of slavery into the West during the Missouri crisis of 1819–1821, and ended his life as president of the American Colonization Society, an institution dedicated to the permanent relocation of African-Americans to another continent. Like Thomas Jefferson, his friend and predecessor in the White House, Madison balanced a watery (and usually private) antislavery sentiment with a profound squeamishness about living alongside black people in freedom. (In his 1785 Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson insisted that American abolition would require a double effort: black people should be freed from slavery and then “removed beyond the reach of mixture.”)

The intellectual and political limitations of these antislavery slaveholders became even clearer after 1815, when the rise of cotton offered fretful planters in Virginia a lucrative alternative to manumitting their slaves or persuading them to settle in Liberia or Haiti. Between 1820 and 1860, for every African-American colonized in Liberia nearly one hundred were driven from the Upper South to the cotton and sugar fields of the Deep South. Madison and Jefferson, who had specified that enslaved people be colonized as a condition of their emancipation, remained adamantly theoretical in their antislavery convictions. Both men clung to colonization throughout their long lives—Jefferson died in 1826, Madison in 1836—despite clear evidence both that American slavery was expanding and that African-Americans would not consent to their expatriation. Jefferson, who owned more than six hundred people across his long life, freed only five slaves in his will. (Two of those were his sons.) Madison freed none.

In making the case for an antislavery Founding, Wilentz misses the most obvious and historically plausible defense against the charge that the Founders facilitated the full horrors of US slavery. In 1787 white Americans could still indulge in the belief that the historical tide was turning against human bondage. The cotton gin had not yet been invented, and the cotton belt remained in the possession of its Native American inhabitants. In the 1780s, a chorus of international antislavery activists—such as Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce, Phillis Wheatley, Olaudah Equiano, Anthony Benezet, and Jacques Pierre Brissot—believed that the force of public opinion could overturn the power of the slaveholders. Britain and the United States seemed poised to ban the slave trade; these activists predicted that, without new arrivals from Africa, slavery would wither and die. Every delegate in Philadelphia should have known that the Constitution’s protections for slavery would slow this antislavery tide; but many might have told themselves that they were only delaying the inevitable.

This interpretation may be overly generous to the Founders, many of whom had already concluded that racial coexistence after emancipation would be as great a challenge for prejudiced white people as ending slavery. But the argument that the Founders couldn’t foresee the horrors of the cotton belt seems more convincing than the suggestion that James Madison slipped in antislavery language for Abraham Lincoln to use during the 1860 presidential race. So why is Wilentz so interested in a form of antislavery originalism? The answer, I think, lies in politics rather than history. No Property in Man began as a series of lectures at Harvard in 2015. That year, Wilentz got into a spat with Bernie Sanders after the presidential candidate told an audience in Virginia that the United States “in many ways was created…on racist principles.” Wilentz, in a New York Times Op-Ed, dismissed “the myth that the United States was founded on racial slavery” and accused Sanders of “poison[ing] the current presidential campaign.” To describe the Founding as racist was, Wilentz wrote, to perpetuate “one of the most destructive falsehoods in all of American history.”

Wilentz has long been a liberal activist. For more than a quarter-century, he faithfully supported Bill and Hillary Clinton. During the Lewinsky scandal in 1998, he warned Congress that “history will track you down and condemn you for your cravenness” if Bill Clinton was impeached. In a 2008 editorial in The New Republic, he accused Barack Obama and his campaign team of keeping “the race and race-baiter cards near the top of their campaign deck” during their battle with Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination. He has been a particularly sharp critic of those who’ve rallied behind candidates to the left of the Clintons. In a recent article lamenting the Sanders phenomenon, Wilentz accused the left of being irresponsible in its economic promises, solipsistic in its embrace of identity politics, and disrespectful toward the achievements of the liberal tradition. Trashing the Founders is, for Wilentz, another sign of progressive immaturity.

At a public event in Florida last spring, the distinguished historians Joseph Ellis and Gordon Wood also criticized what might be called the Bernie Sanders view of the Founding. Ellis complained that college professors were now telling students that the Founders were “the deadest whitest males in American history.” Instead of learning about the nation’s many accomplishments, students were getting “anti-history,” in which slavery and Native American dispossession had been placed at center stage by reckless educators. “Those are storylines worth exploring,” Ellis conceded, “but for that to take the form it has taken, it means young people coming into College don’t learn about the Revolution, the Constitution, the coming of the Civil War.” No Property in Man, with its forceful insistence on the Constitution’s antislavery position, is a perfect response to the “anti-history” produced by a younger generation of scholars.

Do we weaken our politics when we argue that the Founders protected slavery or that they struggled to see people of color as equals? Wilentz thinks so, and he has a powerful figure to help him make the case. Frederick Douglass became an international celebrity on the abolitionist lecture circuit in the 1840s. Working alongside William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips, he at first embraced Garrison’s view that the Founders were fatally compromised by their protections of slavery. “The identical men who…framed the American democratic constitution,” Douglass told a crowd in London in 1847, “were trafficking in the blood and souls of their fellow men.” This, he said, was a stain on everyone in the United States, not only southerners: “The whole system, the entire network of American society, is one great falsehood, from beginning to end.”

The Garrisonians believed that the northern states had a duty to secede from the South, and that participating in elections would dignify a system that was rotten to the core. In the 1850s, Douglass broke with this strategy. He began to argue that the Constitution was a “glorious liberty document” that, despite its proslavery effects, contained “principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery.” His old ally Phillips had scoffed at “this new theory of the Anti-slavery character of the Constitution.” Wilentz, however, praises Douglass for realizing that an antislavery understanding of the Founding might have more political traction than the theatrical recusals of the Garrisonians. When Wilentz discusses the Garrisonians’ righteous fury at the constitutional “compromise” on slavery, it’s hard not to think about Sanders and his supporters: “For the Garrisonians, morality dispelled context and bred certitude; anything short of revulsion at that compromise, rendered as condoning evil for the sake of commercial profit, signified grotesque complicity in slavery.”

Wilentz casts the Garrisonians as naive dreamers whose ideological purity stymied their political influence. But No Property in Man has a narrow understanding of antislavery politics, focused principally on Congress and debates among white elites about the propriety of slavery’s expansion. There’s no room in Wilentz’s account for the men and women, black and white, who struggled to establish pathways out of slavery via the Underground Railroad, or who waged battles in statehouses, in courts, and on the streets to establish the rights of black people within the United States. (Martha S. Jones’s revealing new book Birthright Citizens, which explores many of these aspects of antislavery politics, marks a whole field that entirely escapes Wilentz’s gaze.)

Then there’s the unfortunate fact that many of Wilentz’s antislavery activists—whom he loosely describes as “abolitionists”—were actually advocates of colonization. The project of removing black people from the United States drew adherents from the North and upper South until the 1840s and beyond, a fact that appalled the Garrisonians and supported their belief that slavery and racism were national rather than regional crimes. If we accept, as Wilentz argues, that northerners, along with some sympathetic or unconsciously radical Virginians, essentially doomed slavery by denying property in man in 1787, we indulge a familiar story in which the racial sins of the United States effectively become sins of the South. Garrison and his followers were ruthless in dismissing that convenient fiction. “Slavery is not a southern, but a national institution,” wrote Garrison’s newspaper in 1843, “involving the North, as well as the South.” That this was a hard truth for many northerners to hear—then and now—makes it no less important as a political insight.

Although the subtitle of No Property in Man promises that the book will explore “slavery and antislavery at the nation’s founding,” it will not convince historians of the early republic who have struggled to find antislavery sentiments in the Founders’ intentions. The book is more interesting on the efforts of legislators, reformers, and radicals to work out the implications of “no property in man” through debates over territorial expansion in the following decades, and on the fissure over principles and political participation in the abolitionist activism of the 1840s and 1850s. Wilentz falls short of his central goal: to persuade readers that the Founders planted an antislavery seed that bore fruit in 1860. His book succeeds when it demonstrates that the political abolitionists of the 1850s creatively refashioned the founding story for their own ends. In doing so, they were acting not as historians but as activists; and it’s no surprise that Wilentz, while approaching us as the former, is as much the latter as any of his subjects.