In the late 1820s a Mughal scholar named Khair ud-Din, who was working for the East India Company at its opium factory in Patna, began work on a monumental history. The Book of Cautionary Tales attempted to explain how a handful of traders from the furthest rim of Europe, “men who had yet to learn to wash their bottoms” and who worked not for a nation-state but for a mere corporation based in a small office five thousand miles away in London, had managed, in less than half a century, to conquer the richest empire on earth—that of the Great Mughals of India. Khair ud-Din writes:

From Babur [the conqueror] to the Emperor Aurangzeb, the Mughal monarchy of Hindustan had grown ever more powerful, but then there was war among his descendants, each seeking to pull the other down…. Disorder and corruption no longer sought to hide themselves, and the once peaceful realm of India became the abode of Anarchy. Soon, there was little substance left to the Mughal realm: it had faded to a mere name or shadow or dream.

By 1803, when the East India Company captured the Mughal capital of Delhi and the blind monarch Shah Alam, sitting strangely poised and dignified in his ruined palace, it had trained a private security force of around 200,000—twice the size of the British army—and marshaled more firepower than any nation-state in Asia. In just over forty years, a small group of businessmen had made themselves masters of almost all the subcontinent, succeeding an empire where even minor provincial nawabs and governors ruled over areas both richer and larger in size and population than the biggest countries of Europe.

But what looked like the end of civilization in Delhi looked quite different in other parts of India, as a century of imperial centralization under the Mughals gave way to a revival of long-dormant regional identities, states, and forms of governance. Between the beginning of the collapse of the Mughal Empire at the death of the Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707 and the final victory of the East India Company and its nationalization in the mid-nineteenth century, the decline and disruption of the Mughal heartlands around Delhi were matched by astonishing growth, prosperity, and rebirth in the peripheries.

In the center of India, the city of Pune and the Maratha hills, flush with loot, entered their golden age. For Jaipur, Jodhpur, Udaipur, and the other great Rajput courts, this was an age of resurgence as they regained their independence and began building many of their most magnificent forts and palaces. To the east, in Awadh, the baroque towers of Lucknow rose to rival those built by the Nizam in Hyderabad to the south. The Rohilla Afghans, the Sikhs of the Punjab, and the Jats of Deeg all began to carve independent states out of the cadaver of the Mughal Empire. In Tanjore in the far south, Carnatic music received enlightened and transformative patronage from the Maratha court, which had just seized control of that ancient center of Tamil culture.

Most unexpectedly of all, at the other end of the subcontinent, the remote Punjab hill states of the Himalayan foothills entered a period of astonishing creativity. Mountain fortresses suddenly blossomed with artists, many of whom had been trained in the now-defunct Mughal ateliers, each family of painters competing with and inspiring one another in a manner comparable to the rival city-states of Renaissance Italy: small but wealthy centers of courtly civilization ruled by discriminating aristocrats and intellectuals with an unusual interest in the arts extended lavish patronage to a select group of utterly exceptional artists. Some of them painted images that were not only of extraordinary beauty but also explored mystical and philosophical concepts that have rarely been expressed in painting before or since.

The revival and flourishing of these different painting ateliers has been the focus of much recent art historical attention, and this year two remarkable books have shed fascinating new light on this age of anarchy and reinvention. Manaku of Guler: The Life and Work of Another Great Indian Painter from a Small Hill State, by India’s leading art historian, B.N. Goswamy, accompanied an exhibition in Chandigarh, and has completed his lifetime of research on the most talented of all the families of artists then at work. The book completes a diptych Goswamy began in 1997 with Nainsukh of Guler: A Great Indian Painter from a Small Hill-State. Karni Jasol’s Peacock in the Desert: The Royal Arts of Jodhpur, India tells the story of the arts of one of the foremost Rajput courts in Rajasthan and accompanies a wonderful exhibition organized by Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts in collaboration with Mehrangarh Museum Trust in Jodhpur. These two exhibitions and their accompanying books do much to illuminate this politically disrupted but artistically creative period of South Asian history.

Advertisement

It was in Guler, one of the smallest and most obscure of Rajput states, that came to flourish arguably the most talented of all Indian painter families of the eighteenth century. The patriarch of the clan was a Brahmin named Pandit Seu. His youngest son, Nainsukh, emigrated to another small principality, Jasrota, where his close relationship with the ruler, a foppish young aesthete named Raja Balwant Singh, produced some of the most intimate and celebrated painting of his day. Nainsukh brought together all the precision, humanism, realism, and detail of the Mughal tradition, the bright colors of Rajasthani painting, and the bold beauty of early Pahari art. To this he added humor, refinement, and, above all, a precise, sharply observant eye. He broke free from the formality of Indian court art to explore quirky human reality, stripping down courtly conventions to create paintings full of living individuals.

Nainsukh’s brilliance has done much to eclipse the other members of his family, but for the last twenty years Goswamy, who first cataloged and defined his work, has been working on the more philosophical and religious output of his shadowy but no less accomplished elder brother, Manaku. Goswamy, now in his mid-eighties, has given detail, texture, and individual character to an anonymous group of artists originally known only by place-name and school. Manaku of Guler, which tentatively ascribes a huge corpus of previously unknown and unrecognized masterpieces to Manaku, is a revelation.

If Nainsukh relished observing the secular world of the court and recording the intimate habits and routine of Balwant Singh, his brother’s thoughts dwelled on the more abstruse and abstract world of Hindu philosophy, mythology, and devotional poetry. Unlike the artists of Mughal India, Manaku showed little interest in portraiture, history, or memoir. Instead his life’s work was devoted to giving visual form, in many cases for the first time, to some of the greatest works of Indian philosophical speculation.

The earliest works we possess that are possibly from the hand of Manaku are a few large-format illustrations of a single episode of one of the two great Indian epics, the Ramayana. These concern the section of the story in which the hero, Lord Ram, is besieging Lanka, the island fortress of the demon Ravana, in order to retrieve his abducted wife, Sita, the Helen of Troy to this Indian Iliad. The rest of the surviving images from the series appear to be in the hand of Manaku’s father, Pandit Seu, and Goswami concludes that it marks Manaku’s apprenticeship.

Manaku progressed to illustrating Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda, a twelfth-century devotional text that records the passionate erotic adventures of the irresistible cowherd-god Krishna, as he pursues his loves on the banks of the Yamuna, and particularly his stormy affair with the beautiful Radha. The explicitly sensual epic culminates in the final union of the divine lovers after cycles of separation, longing, and despair. The world Manaku sets out to illustrate was, according to Goswamy, “idealized, lyrical, soaked in real passion but in so many ways other-wordly at the same time.” “Intense colours mark his work,” yet “there is great precision in the way he draws…. Trees and leaves in his hand take on a life of their own…now to shield the lovers from public gaze, now to separate episodes, now to merge with the lovers’ bodies or to pick up their various hues.”

Manaku’s masterpiece, however, is a long and unfinished cycle of illustrations of the Bhagavata Purana, “works of great brilliance…breathtaking in their range and energy,” which must have taken years of labor and perhaps included several hundred individual folios of paintings. Fragments survive of an earlier cycle of illustrations, but Manaku’s work here, produced at the peak of his power, perhaps in the 1740s, is far more sophisticated and contains some of the most astounding images in Indian art. One especially powerful sequence shows the cosmic war against evil waged by the boar avatar of Vishnu, Varaha: “One can almost sense the very heavens shake and tremble with sounds that fill all quarters, and a shower of weapons falls from the sky,” writes Goswamy (see illustration at top of article).

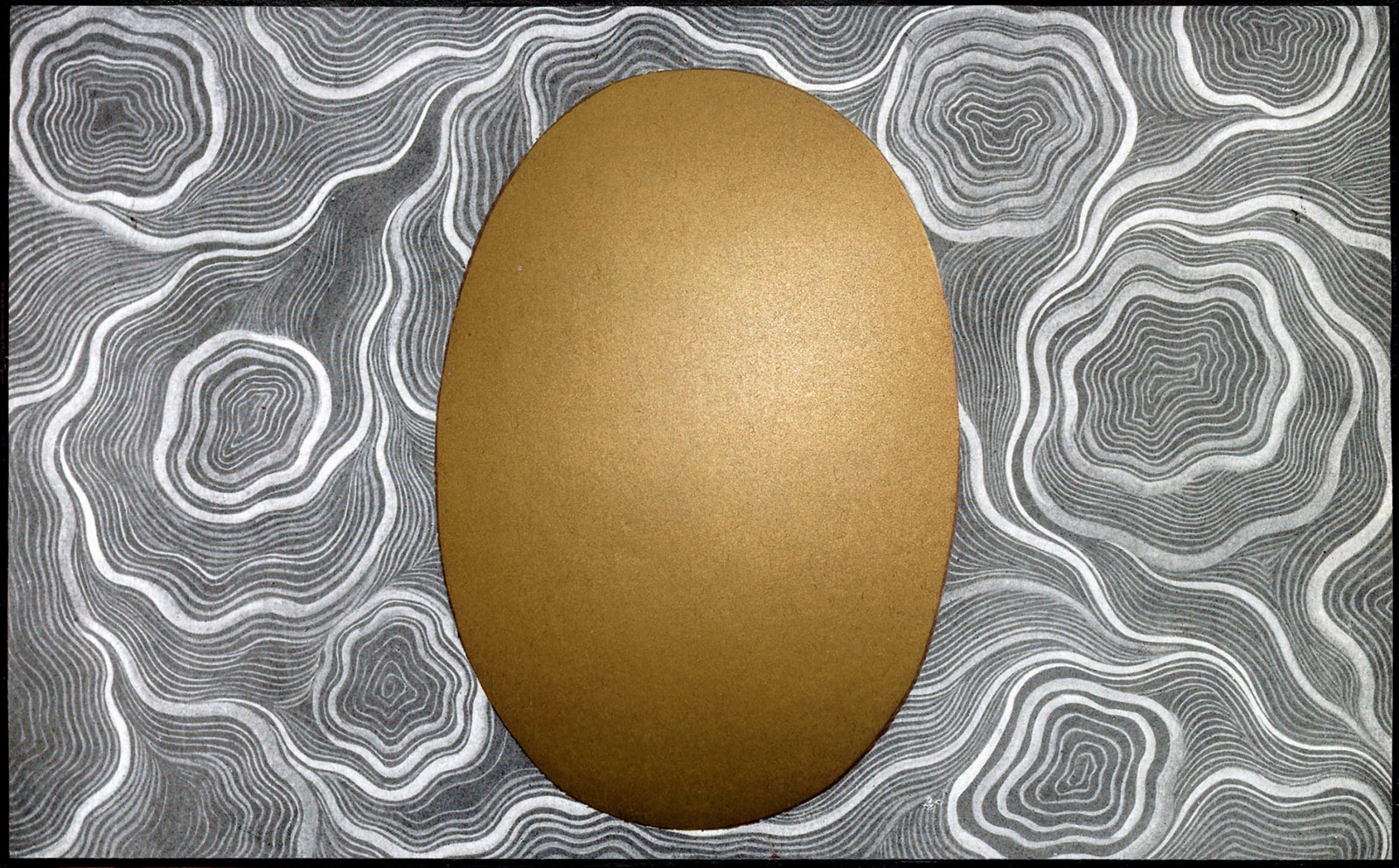

Perhaps the greatest of all is the image of Hiranyagarbha, a form beyond sense, the “golden womb” or cosmic egg that in the creation myth of the Bhagavata Purana “was present at the beginning…upholding heaven and earth… by whom the sky was made profound and the earth solid, by whom heaven and the solar sphere were fixed, who was the measure of the water in the firmament.” To illustrate this concept, Manaku painted an image stunning in its abstraction and simplicity: a single vast, golden, gleaming egg, floating over “concentric whirlpools and eddies, like giant rings of time on timeless waters.”

Advertisement

The collapse of Mughal authority that gave the Punjab hill courts their freedom also liberated the ancient Rajput states of Rajasthan. Almost all these courts, as well as many of the smaller durbars of the village-level thakurs—squires—went on to produce quite distinct schools of painting, but perhaps the most dazzling was that of Jodhpur.

Jodhpur was far more central to the Mughal empire than the obscure hill states of the lower Himalayas, and the Rathores of Jodhpur were leading allies of the Mughal emperors, connected to them by a cat’s cradle of marriage alliances, until 1586, when a Jodhpur princess married Akbar’s son Salim, the future emperor Jahangir. The son of this union was the emperor Shah Jahan, the builder of the Taj Mahal, during whose reign Jodhpur princes held senior posts at the imperial court. They appear in positions of great prominence in the durbar scenes depicted in what is perhaps the most ambitious of all Mughal manuscripts, the Padshahnama, some of whose pages—the apogee of Mughal artistic achievement—have been lent to the “Peacock in the Desert” exhibition from the Royal Collection in Windsor Castle.

The earliest painting that survives from Jodhpur shows the unmistakable stamp of Mughal realism and artistic refinement. This only intensified during the period of Mughal collapse, as the courts offered generous patronage to painters left unemployed at the Mughal court, in several cases luring artists from Delhi: artists working in a Mughal style were often paid more for their painting than local painters. In 1719, after the death of his patron, the emperor Farrukh Siyyar, the imperial artist Bhavanidas shifted from Delhi to the Rajasthani court of Kishangarh, just beyond Jaipur; but under Rajput patronage, the painting of Bhavanidas and his family underwent a profound change, as they took Mughal traditions of portrait realism and used them to illustrate Hindu devotional subjects in a palette supercharged with the brilliant pigments of Rajasthan.

A son of Bhavanidas, Rai Dalchand, moved on to Jodhpur. Dalchand’s Mughal training is shown in the control, delicacy, detail, and psychological realism he manages to evoke in each of his intensely realized portrait heads; yet there is an extravagant mannerism at work as he shows his subjects in court sitting with expanded chests and arched backs, which somehow adds to the feeling of aloof courtly grandeur. Two of his greatest masterpieces are on view in the exhibition. One is An Evening Performance for Maharaja Abhai Singh (circa 1725), in which the maharaja sits back on his throne to watch a lively troupe of female musicians sing, dance, pirouette, and play as moonlight and candelabras illuminate the white marble of the palace in the encircling gloom.

Abhai Singh’s troublesome and scheming brother, Bakhat Singh, was also a great patron, but employed a very different set of local artists who were trained in the indigenous artistic traditions of Rajasthan rather than those of Mughal Delhi. Maharaja Bakhat Singh first appears in a sub-Mughal double portrait with the father he had murdered, Maharaja Ajit Singh. As part of the assassination plot, Bakhat Singh’s elder brother succeeded to the throne, but the patricide took possession of the desert fort of Nagaur. This he turned into his artistic laboratory, where he gave his court artists free range to develop a new hybrid Nagaur style.

Bakhat occupied Nagaur just as the Mughal empire was beginning to collapse and the kingdom of Marwar was beginning to reclaim Jodhpur’s independence from Delhi. But far from depicting himself as some anti-Mughal freedom fighter—the way some patriotic Rajasthani textbooks still like to commemorate him—he chose to represent himself as a sensual hedonist. Amid the scented gardens of the great pleasure palace of Nagaur, Bakhat appears to have pursued his pleasures with impressive single-mindedness: one of the restorers has estimated that the murals he commissioned for the palace contain images of four hundred beautiful women—alongside only three images of men and five of babies.

Paintings from Nagaur at this period are almost entirely filled with depictions of the maharajah surrounded by his women: they fill his pools and bedrooms, fan him with peacock feathers, and entertain him with their sweet singing and dancing and sarangi playing. Some of the images show bacchanalian parties degenerating into full-scale orgies, with the nearly naked Bakhat Singh splashing in a pool filled with his concubines. To the left and right, bedrooms are prepared for the athletics of the night to come.

Bakhat’s successor, Vijay Singh, had more interest in religion than his hedonistic predecessor. Many of the images commissioned by Vijay illustrate the great narrative Vaishnavite epics, especially the Ramayana and the Krishna Lila, and interestingly are almost exact contemporaries of the images produced in a very different style by Manaku in Guler. The huge poster-sized leaves of these manuscripts were probably brought out and pointed to by bards as they told the great Hindu epics to rapt audiences in the court, and can be seen as precursors to the televised Hindu epics that still hold India in thrall.

The tale of Lord Ram’s exile, struggle, and redemption is told through a series of images whose teeming narrative energy seems somehow to tap into the vivid, larger-than-life power of the epics: groups of meditating sages with their hair woven into beehive topknots and dreadlocks sit in wooden huts with thatched roofs, meditating and performing their austerities, while Krishna’s gopis, or female cowherds, search for their lost clothes and the palace ladies lounge amid the fountains of their zenanas. Out on the bare hillsides and deep in the jungles, peacocks and white herons flit between mango orchards and banana plantations, while exultant elephants cavort in the monsoon rain beneath mountains of lightning-emblazoned purple clouds.

The most extraordinary images are those that show the Durga Charit, a text that celebrates the martial exploits of the Rajputs’ principal female deity and commemorates her great victory over the buffalo demon. Here for the first time we see a brilliantly innovative abstraction, which a generation later became the hallmark of the Jodhpur style, as the artist fills the page with silver-black waves in his attempt to depict the cosmic vacuum left by the sleep of the great god Vishnu. Amid this cosmic chaos, two hideous dog-headed demons emerge from nowhere to challenge the unprotected creator god Brahma, as Vishnu lies asleep under his canopy of cobra heads. It was under Vijay’s eventual successor Man Singh that this style of dreamy abstraction became fully formed, and the Jodhpur atelier came into its own.

At first, it seemed very unlikely that Man Singh would ever come to the throne. An ambitious uncle, Bhim Singh, had driven the young prince from Jodhpur and brutally slaughtered all his male relatives. By the beginning of the hot summer of 1803, the usurping uncle had succeeded in surrounding and besieging his nephew in the desert fortress of Jalore. As the siege wore on, the beleaguered young prince found solace in the teachings of an esoteric yogi, Dev Nath, who lived within the fort.

The Naths were a sect of wandering monks and ash-smeared mystics who had invented the techniques of hatha yoga seven hundred years earlier. Their exercises and breathing techniques were believed to give them great supernatural powers: to heal the sick, to fly, to see into the future, and to hear and see over vast distances. Indeed, if followed to the end, their techniques were said to turn devotees into immortal beings, or mahasiddhas, who had powers greater than the gods.

Just as the fugitive was about to surrender to his murderous uncle, Dev Nath approached him with what he said was a divine message: if the prince could hold out until the autumn festival of lights, Diwali, he would not only keep the fortress of Jalore but regain the whole of his father’s kingdom. On hearing this, Man Singh seems to have undergone a conversion:

With his heart and breath he continuously worshipped Nathji at the incomparable Nath temple in the fort. He cared neither for himself nor for worldly affairs as the greatness of Nathji enveloped his heart.

A few days later, the uncle suddenly died, and his principal general promptly declared his support for Man Singh. They marched on Jodhpur, where Man Singh’s coronation was celebrated in January 1804. Shortly afterward, the new maharajah was initiated into the Nath order, and the Nath yogis became the effective rulers of the kingdom, advising the maharajah on policy and taking over from hereditary nobles every senior administrative post. Man Singh threw himself into a life of pleasure—in “Peacock in the Desert” we see him taking on a team of Jodhpur princesses at polo, while giving the reins of the administration to the Naths.

It didn’t take long for the Naths to begin abusing their new power: they kidnapped women and men to induct forcibly into their order and seized property and land for themselves. The thirty years of Nath supremacy in Jodhpur are not remembered as a happy interlude in the history of the kingdom of Marwar. But they were a golden age in the history of its painting.

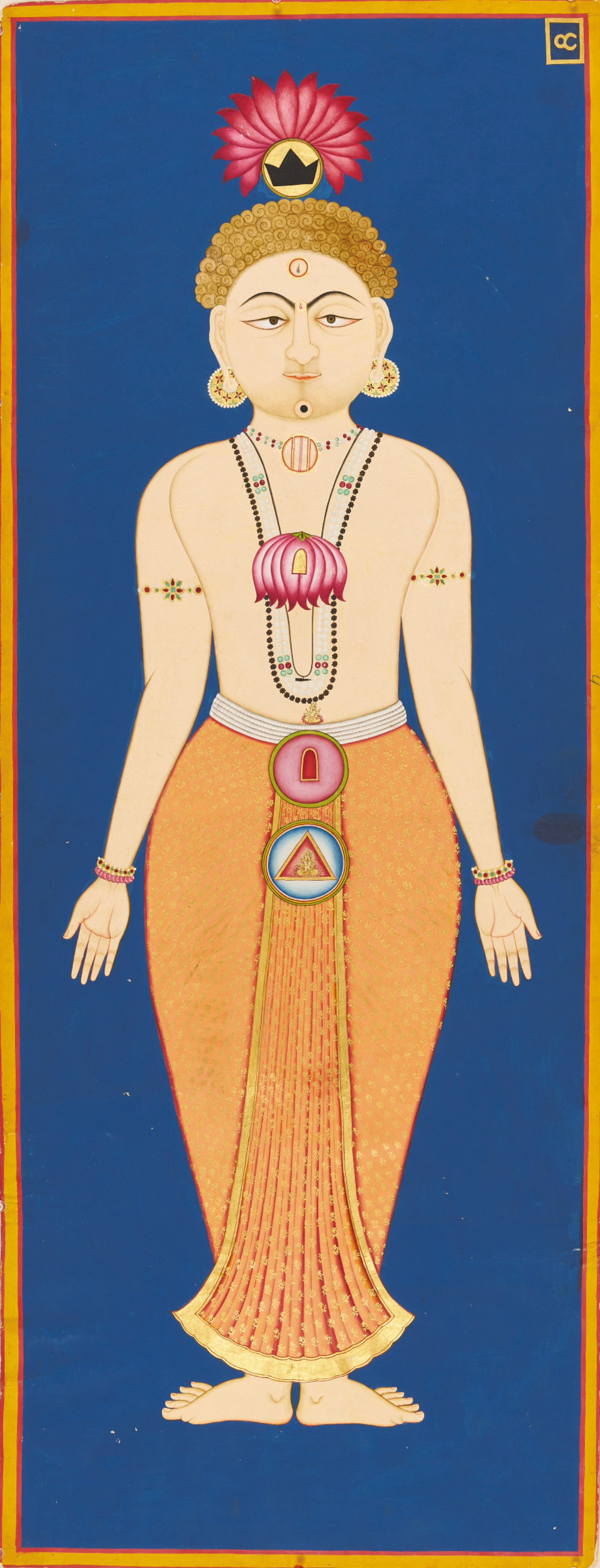

There are sadly only a limited number of Man Singh–period images on view in “Peacock in the Desert,” but they are among the glories of the exhibition. The highlight is a magnificent Cosmic Body, called Chakras of the Subtle Body. Drawing on Jain precedents, the Naths believed the universe was held within the giant body of a cosmic man. For them, it was not just that the universe was shaped like a huge body; the self and the universe were one. Heaven and hell, the cosmos, the physical world—all these were perceived as existing inside the transmuted and perfected yogic body. The Chakras of the Subtle Body illustrates this idea. Wearing only an orange lungi, a nearly lifesize yogi stands with his palms extended in yogic posture, with different chakras spaced out over his face, feet, arms, and torso.

It was under the joint rule of Man Singh and the Naths that Marwari painting reached heights of Rothko-like abstraction and mystical strangeness. Esoteric ideas take wing in sublime forms of fabulous, dreamlike intensity. They illustrate a different philosophical world from the heroism of the great epics, taking us far above the jungles and palaces of the Ramayana to the higher spheres of mystical yogic speculation: cosmic oceans lap against figures incarnating divine principles such as Purusha (Consciousness) and Prakriti (Matter). Plains of unbroken gold represent the essence of nothingness or the formless absolute that preceded the beginning of the universe. These are images that do not tell religious stories so much as attempt to reflect on eternity and address the great mysteries of human existence: What are we doing here? Who created us? Where are we going?

Perhaps the most spectacular of these was painted by a remarkable Muslim artist named Bulaki, who seems to have stood out among the largely Hindu artists of the Jodhpur atelier and was sometimes simply known as the “Musslman chitara”—the Muslim painter. Like Manaku attempting to paint the Cosmic void, Bulaki set himself the impossibly difficult task of visualizing the origin of all existence and the void that preceded it. Bulaki’s daring solution is seen in a masterpiece entitled Three Aspects of the Absolute, which sadly is not included in “Peacock in the Desert” but was shown in an earlier Jodhpur exhibition, “Garden and Cosmos,” at the Freer Sackler in Washington, D.C., in 2008. The image is a triptych of three large squares. One is filled with a pure, shimmering undifferentiated field of gold, representing Brahma, the abstract, formless “supreme, transcendent, immeasurable” Absolute. In the second frame a Nath siddha appears: the perfected being of Nath mysticism hovering in space. The third frame shows a silver light emerging from the body of the Nath siddha, so bringing matter and hence consciousness into being.

The story of the growing arrogance of the Nath order, which brought about their fall, is well told here. In the early paintings, Nath yogis are shown closeted in their monasteries. Later they emerge to take over the kingdom. In one image, the immortal ascetic Jallandharnath is depicted blessing a bowing Maharajah Man Singh. In another, Man Singh’s guru Dev Nath is shown in durbar wearing the king’s own costume, an unmistakable declaration that he is the co-ruler of Marwar, not just adviser but spiritual preceptor and lord of the domain. Finally, in a last act of folie de grandeur, the Naths are shown displacing the gods themselves: in Three Aspects of the Absolute, the Nath siddha precedes Brahma, the Creator.

Such overconfidence and self-aggrandizement had fatal consequences. Dev Nath was assassinated in 1815. By the late 1830s, the nobles were petitioning the British, who were beginning to extend their influence into Rajasthan, to suppress the order. In 1840, when Man Singh found he was unable to protect the Naths from their enemies, now backed by the East India Company, he stepped down from the throne to live in self-imposed penance as a naked Nath ascetic until his death. The British, as was their practice, placed a puppet ruler from the royal line on the throne, who acted as their proxy.

The rise of British cultural influence in the end brought about the demise of this entire artistic tradition, not just in Jodhpur but across India, as rulers came to believe that their patronage should be showered instead on Western painters working in oils and, later, photographers. But as these two books amply demonstrate, like an oil lamp flickering most brightly just before it gutters, the century leading up to the British conquest was culturally and artistically one of the most dynamic and inventive periods in all Indian art history.