For many who look at Europe from afar, its politics seem interesting only when conceived as a Trumpian spectacle: strongman blowhards attacking hollow liberal elites, a migration crisis at the border, a seemingly unstoppable right-wing international at the gates of power in capitals across the continent. In the months leading up to the elections for the European Parliament in late May, this was the narrative that purported to explain the stakes of the vote. “The European Union, a unique, shared project underpinned by peaceful cooperation, is under threat from forces who wish to destroy what we have achieved together,” read the official EU announcement of the vote. Add a cameo appearance by Steve Bannon, and the all-too-familiar plotline begins to write itself.

On one side, there is the self-appointed defender of the citadel: Emmanuel Macron, the young, photogenic French president, who dons an armor of crisp white shirts and spotless navy suits to tilt at the windmills of nativism and nationalism. Macron’s weapons of choice in this fight tend to be literary allusions—to Julien Benda’s La Trahison des clercs, a favorite, or Hermann Broch’s The Sleepwalkers. One or the other is cited in nearly every speech he gives on Europe, the message of which is invariably that we are all sleepwalking to our doom, and no one—except Macron—is saying anything. Guy Verhofstadt, the Belgian leader of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe, is something of his Sancho Panza, tweeting feel-good platitudes about the European project, sometimes with the flexed bicep emoji, sometimes with the heart-eyed smiley face.

On the other side of this seemingly epic battle for the “soul” of the continent, there is the rowdy trio of transnational nationalists—Italy’s Matteo Salvini, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, and France’s Marine Le Pen. They ramble on about migrants who “say they have escaped from war and then go around…with a baseball cap and a cellphone and sneakers to sell drugs in the parks” (Salvini), about a “Soros empire” run by a Jewish billionaire apparently keen on destroying “Christian Europe” (Orbán), and about “taking back power” for “the people” (Le Pen). Like all the best cartoon villains in public life, they see themselves as world-historical. I spoke with Le Pen shortly after the parliamentary elections, and she assured me that the results were tantamount to “the recomposition of political life.”

The irony is that both the globalists and the nationalists have sought to portray European politics as a Manichaean struggle that ultimately becomes a yes-or-no question. “The question to ask is whether you are a globalist or not, whether you are for borders or not, whether you are for the regulation of international finance or not,” Le Pen told me. “That’s the fundamental choice.” Macron and his allies framed “the fundamental choice” in the same way. “Retreating into nationalism offers nothing; it is rejection without an alternative,” Macron wrote in his official campaign pitch, published in early March in numerous European newspapers. “And this is the trap that threatens the whole of Europe: the anger mongers, backed by fake news, promise anything and everything.”

But this narrative—reductive, binary, emotional—more aptly evokes Europe the musical than Europe the real political entity. The European Parliamentary elections represent the second-largest democratic exercise on earth (after the Indian elections), and the largest in transnational democracy: approximately 510 million citizens are eligible to vote, and 751 deputies are chosen—a number that will fall to 705 once Britain finally leaves the European Union. What is on display in this unique political theater encompassing multiple regions, traditions, and languages is not one narrative but many. Of course the results are inscrutable: in a system of proportional representation, that is precisely the point: no faction decidedly wins or totally loses. One definition of Europe is thus the conversion of cacophany into compromise, however intractable.

In the elections, candidates from national parties campaign as part of pan-European political movements, such as the European Peoples Party (EPP), a group of center-right and Christian democratic parties, or the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), a coalition of social democratic parties. Despite the handwringing about Europe’s being on the brink of apparent disaster, these two mainstream factions remain after this year’s elections the largest and most powerful two groups within the European Parliament—although they lost the overall majority they had enjoyed for decades. In the end, the standoff between Macron and the “populists” was merely a subplot. Despite the headlines, the continent turns out to be one of the only places on earth where ordinary liberals still fare rather well.

The European Parliament is a bizarre legislative body that has emerged gradually and largely outside of public view. Its official seat is Strasbourg, in eastern France, where twelve sessions are held every year, but all other sessions are held in Brussels, the capital of the European Union. That confusion is perhaps inevitable for a body that has never had a clear charter and has always been an afterthought in an organization whose purpose was economic—and not political—integration. There was no provision for a multinational parliament in the 1950 Schuman Declaration, in which French foreign minister Robert Schuman announced that France and Germany would unify their coal and steel industries, and which first established the contours of the European Union. For years the various multinational assemblies that ultimately evolved into the European Parliament were not even allowed to call themselves a “parliament,” a title that was only officially granted in 1987.

Advertisement

Most importantly, there is also the issue of sovereignty, or lack thereof. For decades, the European Parliament—whatever it was called—had no power to make law; that was acquired progressively and often in conflict with national parliaments. The turning point came in 1979, the first year its members were directly elected, which put an end to its being merely a group of national parliamentarians dispatched to a powerless supranational assembly. To this day, the Parliament still cannot introduce legislation of its own: it can only reject or amend proposed laws. These are meant to be drafted by the European Commission, the European Union’s equivalent of an executive branch, although the Parliament can ask the Commission to introduce particular laws, which implies a certain de facto power.

Nevertheless, direct elections have meant that the Parliament is the primary stage for an inchoate but implicit European citizenry. The laws that ultimately emerge from this seemingly arcane body matter: in the soon-to-be twenty-seven member states (once Britain leaves), EU laws take precedence over national laws in the event of a conflict between the two. And they can have effect on a global level. A recent example is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which took effect in May 2018 and has arguably changed the way international corporations use consumers’ personal data more than anything else since the emergence of the now ubiquitous tech conglomerates.

If in the past these elections have sometimes failed to interest many eligible voters and have largely served as occasions for protest votes by those fed up with politics at home, 2019 was different. Voter participation was at its highest in twenty-five years—roughly 51 percent, according to a European Parliament spokesman, although that was not a huge increase over previous years. In any case, the outcome was not nearly as dramatic as those on either side of the manufactured narrative had hoped.

It is undeniable that the fiercely xenophobic, anti-immigrant right-wing parties once confined to Europe’s political fringes now fare better than ever. No national party won more seats than the Brexit Party of Nigel Farage, even if this was something of an outlier: the UK, which is leaving the EU, only decided to hold elections at the last minute, and Farage’s party was the only one to mount a real campaign. In Italy, Matteo Salvini’s Lega won the largest share of the vote, 34.3 percent; in France, perhaps the contest most closely watched, Le Pen’s recently renamed Rassemblement National—led by the charismatic twenty-three-year-old Jordan Bardella—took 23.3 percent. This was a decline from the party’s result in 2014, and it will lose a seat in the new European Parliament that convenes in early July. The outcome was not quite a victory for Macron, who did not receive the resounding endorsement he had sought: his party will have the same number of seats as Le Pen’s.

Still, this was not the populist wave that had been dreaded for months. Salvini had vowed to join forces with Le Pen and others to create a powerful right-wing bloc that could disrupt the European Union from within. But it remains to be seen how these factions intend to exert any real pressure within the complicated system of the European Parliament. They do not all belong to the same pan-European alliance, and Salvini’s ambitions have likely been foiled before the new session has fully begun.1

Orbán still technically belongs to the center-right, pro-EU EPP, although his own party, Fidesz, was suspended from the EPP in March for presiding over flagrant rule-of-law violations in Hungary. But almost immediately after the election, Orbán rebuffed Salvini and tried to appease the EPP, seemingly for a simple reason: within the Parliament, the EPP means power, and Salvini does not. Orbán’s chief of staff said in late June that he did not envisage “much chance for cooperation on a party level or in a joint parliamentary group” with Salvini. Poland’s Law and Justice Party, which won a staggering 45.34 percent of the national vote, has refused to be part of Le Pen and Salvini’s Identity and Democracy alliance, largely because of its support for Vladimir Putin’s Russia. The Brexit Party, whose raison d’être is orchestrating Britain’s departure from the bloc, has also refused to work with Le Pen and Salvini. The right-wing international may have more of a microphone, but this is nowhere near the “Stalingrad” scenario that Bannon predicted before the vote.

Advertisement

The fundamental inadequacy of the globalist–nationalist dichotomy to explain the full complexity of European politics has no better example than the rise of the Greens, who performed significantly well in the more affluent countries of Northern and Western Europe. They took second place in Germany and third place in France, and their relative success should undermine the narrative of Europe as engaged in a Manichaean struggle. If this is not quite the “Green Wave” that some left-leaning commentators have described, it does reflect a fundamentally pro-European strand of the electorate that sees the continent’s traditional center-left and center-right parties as agents of an unacceptable status quo that has failed not only to take climate change seriously but also to address economic inequality, which has risen sharply since 1980, even though Europe remains the most egalitarian region in the world.

“The idea that people like Macron had was to present the choice as if between two options—either the nationalist retreat behind your own walls, or embracing globalization,” Philippe Lamberts, a co-chair of the European Parliament’s Greens alliance, told me after the vote. “We flatly refused,” he said, noting that after Macron’s election, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, a previous Green leader (and “Dany le Rouge” of May 1968 fame), had reached out to the party to try to convince it to join forces with Macron. “Yes, in a way the nationalist populist forces are an alternative of neoliberal globalization. But so are we,” Lamberts told me. “You can have another form that doesn’t respond to globalization with a nationalist approach, but one that aims to put human dignity rather than the maximization of profits at the heart of everything we do.”

The Greens believe that Europe’s traditional center-left parties have discredited themselves, abandoning age-old commitments to social justice in order to win elections, whether by adopting increasingly hard lines on immigration or pursuing market reforms to stimulate sluggish national economies. But the Greens cannot be seen as Europe’s “new left,” either. There were regions—notably Southern Europe, and especially the Iberian Peninsula—where the continent’s traditional center-left performed better than ever. In Spain, the parliamentary elections followed a decisive win for Pedro Sánchez, the country’s Socialist prime minister, in a snap election in late April: framed as a referendum on Sánchez’s handling of the Catalan independence crisis, most voters went to the ballot box to voice their support for the young prime minister’s commitment to reducing the austerity measures put in place by the conservative government of Mariano Rajoy. The European parliamentary results were similar: Sánchez’s Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party won 32.8 percent of the vote, the largest share. The same frustration with austerity was expressed in Portugal, where the Socialist Party won 33.4 percent.

In short, these are results that defy facile explanation: they are at once local, regional, and national. If they fit into any narrative, it is one of increased political fragmentation, which was already underway within individual EU member states and is now affecting the EU’s only directly elected institution to a greater degree than ever before.

The cacophony of the parliamentary elections is a sign that politics are increasingly vital in Europe at a supranational level, which befits a region increasingly compelled to act as a transnational entity. First, there is the paradox that the anti-Brussels far right—with its insistence on posing questions about the future and purpose of Europe—has in fact stimulated some degree of pan-European sentiment among voters. This has been true even among the far right’s own supporters: the embarrassment of Brexit Britain has discredited any serious talk elsewhere of leaving the EU. But there is also the deeper reality that the principal challenges Europe has faced in the last decade could not be addressed at the level of the nation-state, which has been rendered powerless by the Eurozone crisis, the migrant crisis, the aftershock of the Brexit referendum, the presidency of Donald Trump, who has already upended much of what was called “the postwar order,” and, perhaps most importantly, the imminent disruptions of climate change.

Each of these crises left Europe with no choice but to take impromptu political action in emergency scenarios that the EU’s founders likely never anticipated. Tracking the evolution of what Luuk van Middelaar calls “events-politics” is the project of his book Alarums and Excursions: Improvising Politics on the European Stage, a brilliant series of case studies that illuminate different points in the creation of a new European political theater unscripted by the innumerable treaties and rules that created the EU as we know it today. Van Middelaar, a former speechwriter for and adviser to the president of the European Council and currently a professor of political theory at the University of Leiden, recounted the history of the European Union in The Passage to Europe (2009). Alarums and Excursions is not about how the EU came to be but about how it will be forced to continue. “Since 2008, crisis after crisis has undermined its foundations, its self-image, its existence,” Van Middelaar writes. “Although as a rule-making factory it had little experience of acting, circumstances left it with little choice. Action was required. Often the Treaty said ‘no’ or ‘not permitted,’ but doing nothing was clearly not an option.”

There was never a single moment that marked the definitive establishment of the European Union, which—as both vision and entity—has continued to define itself since World War II. But the major turning points have all been quiet steps on the way to further economic integration while preserving national sovereignty. Today there is only an incomplete monetary union without a real political contract to manage it—a fragile reality the economist Ashoka Mody has recently called the “EuroTragedy.”2

There was the Schuman Declaration in May 1950. There was the Treaty of Paris in April 1951, when the so-called Inner Six—France, West Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg—expanded the Schuman Declaration by establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). There was the Treaty of Rome in March 1957, when the original six went further, establishing the European Economic Community (EEC), which created a customs union and abolished certain trade barriers. There was the establishment of the European monetary system in March 1979, when French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing convinced his skeptical German counterpart, Helmut Schmidt, to commit to fixed exchange rates. Finally, there was the Maastricht Treaty in February 1992, when the EEC’s twelve member states—the original six plus Spain, Portugal, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Denmark, and Greece—established the European Union as we know it today, promising the introduction of the single currency in 1999 and announcing the fiscal requirement that member states keep their deficits below 3 percent of GDP.

Politically, what emerged was a bureaucratic apparatus designed to ease these ambitious economic transformations but whose real nature—and actual authority—has always remained opaque. The Treaty of Paris had established a “High Authority” in 1951, but the Treaty of Rome nullified that body because member states felt it would potentially supersede the authority of their own national parliaments. What the Treaty of Rome established instead was the first iteration of the European Commission, an executive institution intended to implement Europe’s many treaties with some 32,000 unelected bureaucrats under the charge of an unelected president.

Technocracy has its limits. Toward the beginning of Alarums and Excursions, Van Middelaar recounts an amusing anecdote about a master class he gave for mid-career EU officials in Brussels in the autumn of 2015, when the number of migrants entering Europe by land and sea had reached record levels. The objective of the seminar was to compare the EU’s internal market rules created by former European Commission president Jacques Delors in 1985 to the pressing (and human) challenge of the day, which no treaty had anticipated. “It seemed obvious to me that, 30 years on, Europe now found itself in a different world,” Van Middelaar writes. “From the perspective of Brussels, this proved difficult to see…. At least half of the course participants were unconvinced.”

But a new European politics is nevertheless emerging, Van Middelaar insists, even if its form is not yet fixed. And the migrant crisis is one of his most illuminating case studies: an unanticipated and obviously pan-European problem that had to be addressed in an entirely improvised manner, and through a stronger, or at least more public, executive. “Visibility is a precondition of political authority,” he writes, advancing his theater metaphor. “Democracy demands individuals who publicly take personal responsibility for decisions and who embody institutional responsibility, if necessary attaching their own political survival to it.”

In the migrant crisis of 2015–2016, that individual was German chancellor Angela Merkel, who had already staked her political future on welcoming one million migrants and refugees into Germany. At the time, this was a German decision—an embrace of Willkommenskultur that was not at all shared by neighboring countries such as Austria and Hungary. Those regional tensions began to erupt in August 2015 as the migrant crisis worsened following Merkel’s initial decision: millions of Syrian refugees had been displaced, and in October 2015 as many as 200,000 arrived in Greece alone. Donald Tusk, the president of the European Council, told an emergency summit that autumn, “The greatest tide of refugees and migrants is yet to come. Therefore we need to correct the policy of open doors and windows. Now the focus should be on the proper protection of our external borders.”

Protecting Europe’s external borders while simultaneously preventing migrants from passing through Greece to other EU member states would come close to jeopardizing the promise of borderless, visa-free travel, one of the foundational principles of the bloc. But in March 2016 Merkel, along with Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte, reached a compromise with Turkish president Recep Erdoğan. In a one-for-one exchange, Turkey would accept all the asylum seekers who landed in Greece if the EU relocated Syrian refugees from camps along the Turkish border. The number of new arrivals began to fall, but what price had Europe paid? Officials had no way of knowing whether Erdoğan was actually sending refugees back to war-torn Syria instead of housing them, or whether the blockade in the Aegean Sea led migrants to try the more dangerous Central Mediterranean route to Europe via Libya, where some have reportedly been sold as slaves. “I would like to recall that the main goal we decided on was to stem irregular migration to Europe,” Tusk said in April 2016.

The politics of improvisation is not always pretty. The migrant resettlement scheme was also a moment when, as Van Middelaar notes, Europe “was forced to close borders, disavow principles, get its hands dirty.” But this was ultimately a decision that clearly represented the emergence of something new in Europe, often dismissed as a byzantine bureaucracy that Henry Kissinger could never figure out how to reach by phone. Here was realpolitik on the fly, a necessary—and even urgent—tactic for a political entity with collective problems to solve.

The recurring question is how many European citizens actually feel implicated in these new collective politics and to what extent there is a demos, a body politic that sees itself as European. One concrete plan to “democratize” Europe—to stimulate a more active European citizenry—is the proposed Treaty on the Democratization of the Governance of the Euro Area, or T-Dem, included in the collection How to Democratize Europe. Devised by the French economist Thomas Piketty and a number of prominent European intellectuals in 2017 and 2018, the treaty’s aim is to create—somehow within the purview of existing European legislation—a separate parliamentary body, four fifths of which would be drawn from national parliaments, with the remaining fifth coming from the existing European Parliament.

T-Dem is essentially a version of the blueprint spelled out by the former German foreign minister Joschka Fischer in a speech he gave at Berlin’s Humboldt University in 2000, in which he argued that the “completion of European integration can only be successfully conceived if it is done on the basis of a division of sovereignty between Europe and the nation-state.” By “division of sovereignty,” Fischer meant the establishment of a two-chamber European Parliament that represented both a “Europe of the nation-states and a Europe of the citizens.”

Piketty et al. call this second—and predominately national—chamber the Parliamentary Assembly of the Euro Area, which their treaty presents as a crucial mechanism to uphold “a truly democratic system of governance for the euro area.” The only way to democratize Europe, they insist, is through the embrace of the national parliaments in each respective capital:

Because they remain closely connected to political life in the individual member states, national parliaments are the sole institutions with sufficient legitimacy to democratize this mighty intergovernmental network of bureaucracies that has emerged over the past decade.

And yet this draft treaty never actually explains a crucial question, which is why the European Parliament, either in its current form or some revised form, is inherently less democratically legitimate than all the individual national legislatures. Members of the European Parliament are directly elected by European citizens from Dublin to Warsaw. Why should smaller bodies have a greater intrinsic value?

The Piketty proposal stumbles further in its attempts to respond to austerity politics, ultimately describing a new representative body with specific left-wing policy outcomes in mind, which, as reasonable as they may be in certain cases, undermine the democratic nature of the European Assembly that the authors propose. In the words of the French economist and former Macron adviser Shahin Vallée, who criticized T-Dem immediately upon its publication in French in 2017, “A cardinal principal is that institutional reform is acceptable only if it can be conceived under a ‘veil of ignorance,’ that is, if it is not intended to give power to a particular political group.” T-Dem fails that test.

This is most true in Article 12, which would allow the Assembly to mutualize public debt exceeding 60 percent of a given member state’s GDP. There are also provisions that would permit the new Assembly to confront rising social inequality, by monitoring “tax justice and political voluntarism in the regulation of globalization,” which, the introduction to How to Democratize Europe states, “will achieve substantial and tangible progress in that direction.” These are partisan goals, and they would be better left to members of this theoretical European Assembly to achieve.

But the authors of T-Dem are right to draw attention to the democratic deficit in the European Union, in which member states like Greece, which have received financial assistance from the bloc, are almost entirely deprived of their own economic sovereignty by its terms. “It’s a little bit like complaining when on the moon that there is a deficit of oxygen. There is no oxygen,” said Yanis Varoufakis, the leftist economist who served as Greece’s finance minister during the height of the country’s debt crisis until his resignation in July 2015. “There is zero transparency in Europe and no democratic accountability.”

As for the European Parliament, he insisted that its lack of sovereignty says it all. “When they created the European Parliament, in the 1950s, it was as a way of legitimizing this vacuum of democracy,” Varoufakis told me. Like Piketty, he, too, has a proposal to further democratize Europe—the “Democracy in Europe Movement 2025,” or DiEM25, which aims, among other things, to reinvent Europe’s electoral system to allow for transnational party lists and, in theory, a robust transnational politics.

On a much more concrete level, one relatively simple means of simulating—if not necessarily installing—more European democracy was abandoned altogether: the Spitzenkandidaten, or “lead candidates,” method of choosing the next European Commission president. Favored by the European Parliament and Germany in particular, this would have allowed the European party with a majority governing coalition to see its lead candidate become commission president—pending approval from the European Council (the group of member state heads) and confirmation by Parliament. Manfred Weber, the German politician who was elected as the EPP’s Spitzenkandidat in November, in theory should have been nominated. He wasn’t, having faced strong opposition from European leaders—and especially Macron—for his refusal to expel Orbán from the EPP. Instead the council nominated German defense minister Ursula von der Leyen, a conservative from Merkel’s center-right party. To appease Macron, Christine Lagarde, France’s former finance minister, was nominated to run the European Central Bank. Both were clearly credible—and even historic—choices, but both were entirely dictated by the squabbles of national governments and in disregard of parliamentary preferences.

Despite these problems, the trouble with representative democracy in Europe is not, as Piketty’s proposal assumes, that there can by definition be no genuinely European demos. If one does not quite exist today, the reason could be that there was never a serious attempt to create one, either from the institutions of the European Union that evolved gradually, and sometimes undemocratically, or from the national leaders who came to fill them. “If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere,” said outgoing British prime minister Theresa May at the Tory Party conference in 2016, amid the enthusiasm over the Brexit she ultimately failed to deliver. But these words are nothing but a self-fulfilling prophecy for those who wish them to be true.

For all the criticism directed at Brussels, a reasonable observer could look at the history of postwar Europe and see that its various peoples have grown remarkably closer, not farther apart. The European Union now has open borders, a single market from Portugal to the Baltics, and more or less monthly meetings of member state leaders. What’s more, those member states are now closer to each other than they are to the United States—a reality that would have seemed utterly inconceivable when the Berlin Wall fell thirty years ago. And again, this transformation has occurred informally and organically, within an economic union that never sought to subvert national sovereignty or even to create European citizens. One wonders what might happen if European institutions were recast to instill that sensibility.

With or without EU reforms, the 2019 parliamentary elections show that robust supranational politics are taking root in Europe, which may be more significant than any proposed reform. “Democracy is a way of making social and political conflicts visible,” Van Middelaar writes. “A Union with more commotion and noise, more drama and conflict,” he insists, may help strengthen “the conviction that what unites us as Europeans on this continent is bigger and stronger than anything that divides us.” But this may in fact be the European Union that already exists.

—Paris, July 18, 2019

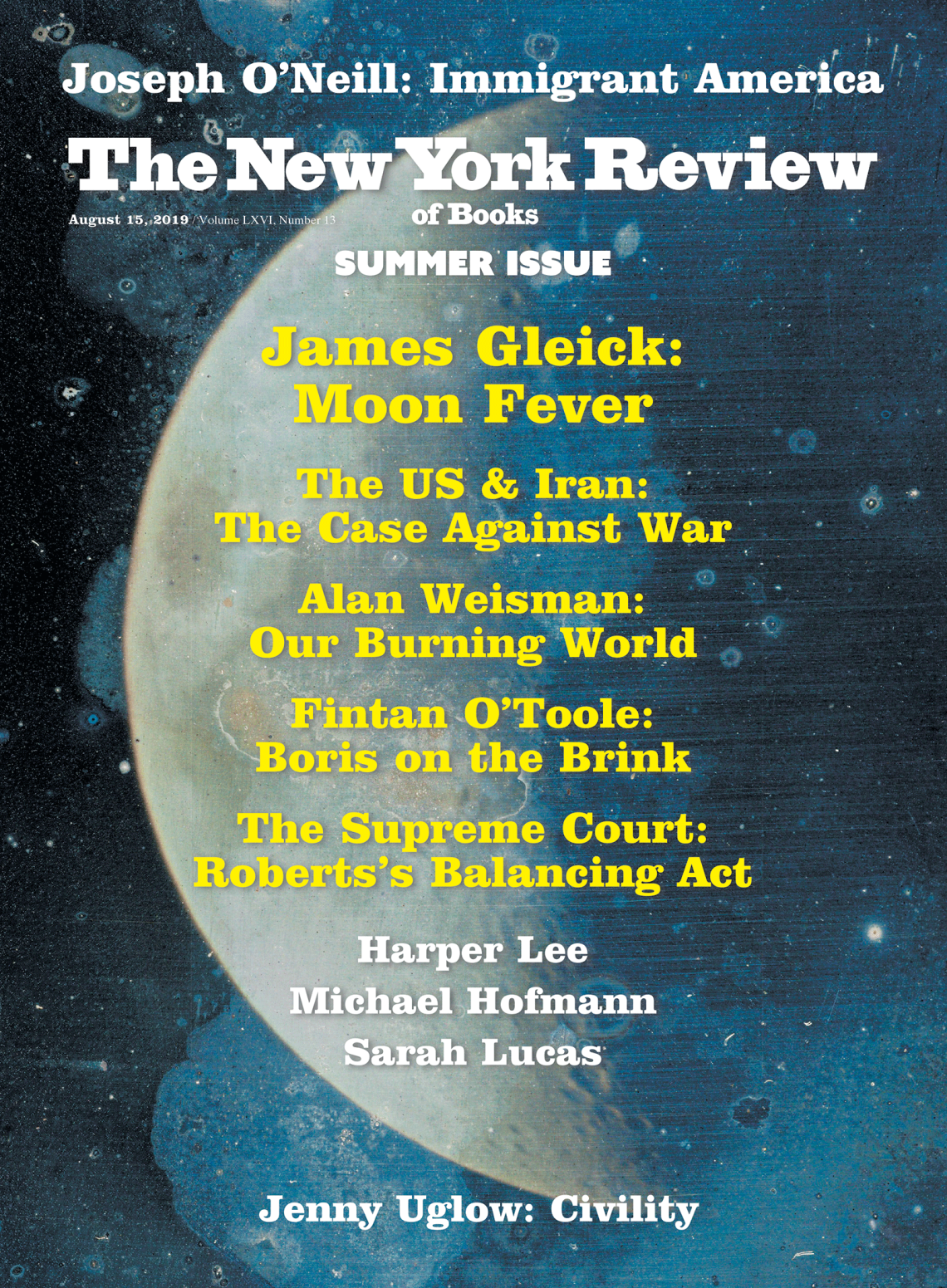

This Issue

August 15, 2019

The Ham of Fate

Burning Down the House

Real Americans

-

1

Salvini’s political standing in Europe has been further diminished following devastating revelations from Buzzfeed, which obtained a tape of Gianluca Savoini, one of his close aides, soliciting Russian oil money in Moscow for Salvini’s party in October 2018. “A new Europe has to be close to Russia as before because we want to have our sovereignty,” said Savoini. Italian electoral law bans large foreign donations and, following the Buzzfeed report, public prosecutors are now investigating. See Alberto Nardelli, “Revealed: The Explosive Secret Recording That Shows How Russia Tried to Funnel Millions to the ‘European Trump,’” Buzzfeed, July 10, 2019. ↩

-

2

See Mody, EuroTragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts (Oxford University Press, 2018). ↩