In response to:

The Great Divide from the May 23, 2019 issue

To the Editors:

James Oakes writes, “It is a commonplace among historians that…in his early career [Lincoln] was something of a Whig Party hack” [“The Great Divide,” NYR, May 23]. I find this statement amazing. How in the world do those words apply to the brave, eloquent, and politically costly words and actions undertaken by the first-term congressman Lincoln in opposition to James K. Polk’s mendaciously undertaken war of conquest against Mexico?

Congressman Lincoln was lonely and indefatigible in his defense of both Congress’s role in the decision to go to war and in attempting to hold Polk accountable for the lies he told to justify the conflict. Rarely has any representative risen to such heights of eloquence as when Lincoln accused the president of having

trusted to avoid the scrutiny of his own conduct by directing the attention of the nation, by fixing the public eye upon military glory—that rainbow that rises in showers of blood—that serpent’s eye that charms but to destroy; and thus calculating, had plunged into this war, until disappointed as to the ease by which Mexico could be subdued, he found himself at last he knew not where.

Warned by his closest political advisers that he was risking his career in doing so, Lincoln persisted:

Allow the President to invade a neighboring nation, whenever he shall deem it necessary to repel an invasion, and you allow him to do so, whenever he may choose to say he deems it necessary for such purpose—and you allow him to make war at pleasure. Study to see if you can fix any limit to his power in this respect.

Given the jingoistic times, his views proved so unpopular with his constituents that he decided to forego a campaign for reelection, and so retired from Congress. In his 1858 debates with Stephen Douglas for the Illinois senate, the latter tried to mock his opponent by accusing him of trying “to dodge the responsibility of [the Republican Party] platform, because it was not adopted in the right spot.” He teased him as “Spotty Lincoln.” Douglas also deployed the same tactics that Polk would use against his critics: insisting that Lincoln had “distinguished himself by his opposition to the Mexican war, taking the side of the common enemy, in time of war, against his own country.” Douglas said it “is one thing to be opposed to the declaration of war, and another thing to take the side of the enemy against your own country, for the war commenced and our army was in Mexico at the time.”

If this is Mr. Oakes’s view of hackery, I say this country could surely use more such hacks as Congressman Abraham Lincoln.

Eric Alterman

CUNY Distinguished Professor of English

Brooklyn College

Brooklyn, New York

James Oakes replies:

I assure Mr. Alterman that I admire Lincoln’s stance against the Mexican-American War as much as he does. But when historians speak of Lincoln as a Whig Party hack in his early years, the years they refer to are the four terms he served in the Illinois legislature beginning in 1834. Though he had few legislative achievements, Lincoln nevertheless earned a reputation as a brutal partisan attack dog. He published pseudonymous letters and anonymous editorials satirizing the religious convictions of his opponents or belittling their manhood. Worst of all was Lincoln’s penchant for race-baiting. He implied that Democrats would give blacks the vote and that Illinois would “be overrun with free negroes.” He described Martin Van Buren’s running mate as “the husband of a negro wench, and the father of a band of mulatoes.” He published fake letters endorsing Democrats in “negro dialect.” That’s the early Lincoln who was, by my standards at least, a partisan hack. The Lincoln who went to the House of Representatives in 1847 was a very different man. In addition to his courageous criticism of Polk’s war, Lincoln voted repeatedly for the Wilmot Proviso, which would have banned slavery from all the territory snatched from Mexico. He also drafted the first statute I know of that would have abolished slavery in Washington, D.C.

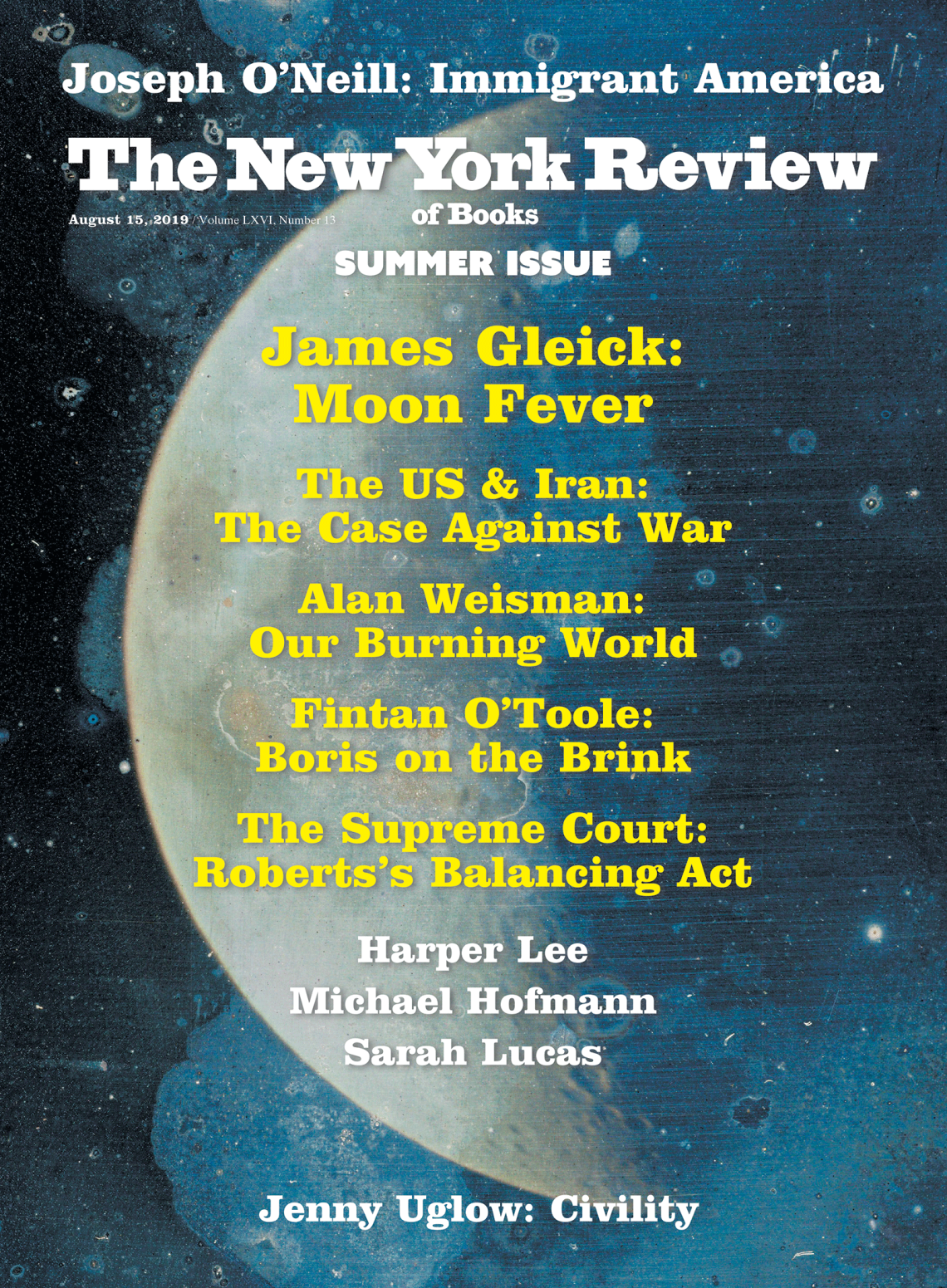

This Issue

August 15, 2019

The Ham of Fate

Burning Down the House

Real Americans