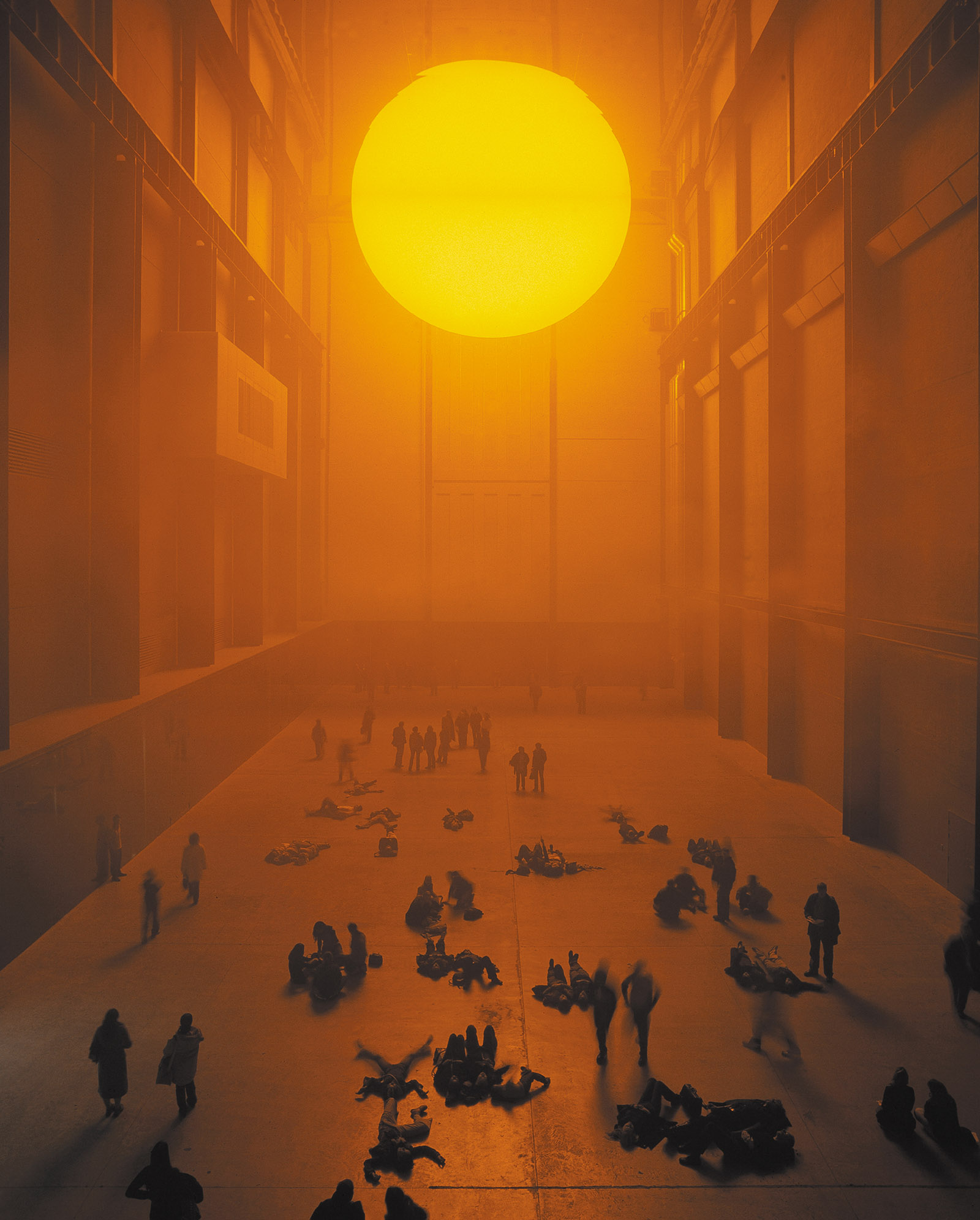

No one who saw it has ever forgotten it: a fat yellow sun hanging inside the colossal Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern gallery, glowing through clouds of swirling mist. Olafur Eliasson’s The weather project, which opened in October 2003, was a magical microclimate created at a moment when weather was on everyone’s mind: a hellishly overheated summer—an early harbinger of the ominous climatic changes to come—had begun at last to release its grip on Europe. If the air outdoors brought a welcome touch of autumn chill, the huge luminous circle of Eliasson’s indoor universe shimmered miragelike above a ruddy haze, making high noon on the south bank of the Thames feel almost like sunset on the veldt. The great sun’s monotone yellow stripped away the other colors, turning everyone and everything into tiny sepia silhouettes. People responded to their transformation in the most extraordinary ways: they lay down flat, flapping their arms and legs as if they could make snow angels on the Tate’s concrete floor, talking to strangers in the mist. No one was tethered yet to a little handheld screen; we were all in The weather project together, fellow participants in a miracle.

Anyone who looked carefully at the mechanics of Eliasson’s installation could see that it was all an illusion. The circular sun was really a semicircular screen, lit from behind by two hundred monofrequency lamps (the kind used for streetlights), reflected in a mirrored ceiling that completed its round outline and seemingly stretched the already grand dimensions of the Turbine Hall to dizzying heights. An upside-down airborne public mimicked the movements of the public below, with an effect as disconcerting as a funhouse, but carried out with simple elegance and on a magnificent scale. Knowing how The weather project worked did nothing to break its enchantment; the whole remained immeasurably, and unpredictably, greater than the sum of its parts. The Turbine Hall has never been as happy as it was in those five months from October 2003 to March 2004.

Eliasson was thirty-six, a Dane of Icelandic ancestry who had spent most of his summers exploring Iceland with his father, Elías Hjörleifsson, an artist who also worked as the cook on a fishing trawler. Their adventures traversing a harsh volcanic terrain and unpredictable seas left a lasting impact on the son. In Olafur Eliasson: Experience, the large retrospective catalog that chronicles Eliasson’s work to date (its cover is the same brilliant yellow as the catalog of The weather project), he recalls that his father and another artist, Örn “Gunnar” Gunnarsson, would

go out sketching and painting, and they’d talk about the moss and the stones and get lost in the various reds and browns and greens. Their artistic toolbox was often mythological and narrative-driven. They’d see trolls’ faces in the sides of the mountains.

At the age of twelve or so, Olafur painted a rocky gorge in which “all the stones had noses and mouths and eyes—to make my father and Gunnar happy, I guess. I grew up surrounded by art that embraced both abstraction and mythology and allowed plenty of space for imagination.”

He also grew up in a world of intense physical activity. At home in Copenhagen, he fell in love as a teenager with American-style street dancing and pursued it with characteristic intensity; his troupe, Harlem Gun Crew, won the Scandinavian breakdancing championship in 1984. Dance, he recalls in Experience, refined his sense of how his body moved through space and showed him how profoundly his awareness of his own placement in the world affected his other perceptions. A recent YouTube video records Eliasson dancing in baggy jeans on the roof of his studio, surrounded by the young people who work with him every day. In middle age, he moves carefully and economically, while they fling themselves into the crazy postures he took in his youth. Like the elderly Greek men who dance their zeibekiko with the ferocious concentration it takes to battle pain, he has reached the point where athleticism must give way to the pursuit of grace: no more stratospheric leaps and gripping tables in your teeth, just an ocean of feeling conveyed in small, deliberate movements.

After his triumph with Harlem Gun Crew, Eliasson entered the Royal Danish Academy of the Fine Arts in 1989. On graduating in 1995, he set up a studio in Berlin, the city where he continues to live and work, in a setting that still affords “plenty of space for imagination.” This summer, sixteen years after he transformed the Turbine Hall, Eliasson has returned to Tate Modern with a retrospective exhibition, “In Real Life,” that ranges from his student days to special installations tailored to the occasion. Rather than the epic immensity of The weather project, the effect of this anthology of an inspired career is almost intimate.

Advertisement

The exhibition’s earliest works are predictably low-budget. Window Projection, a student project from 1990, clearly grew out of his interest in the light experiments of American artists like James Turrell and Robert Irwin. A stencil placed over a projector casts an image on the wall that suggests, in a modest way, a paned window. In 1967, the year of Eliasson’s birth, Turrell was aiming a slide projector at a corner in a similarly low-tech attempt, called Afrum I (White), to wring three dimensions from light striking a planar surface. The result barely hinted at the marvels LED technology would enable him to achieve a few decades later.

Turrell would eventually hide the lamps that produced his intensely colored fields of shifting light. Eliasson, on the other hand, has continued to reveal his methods as an integral part of his artistry. Window Projection may be trying to fool us into thinking that sixteen oblongs of light are a window that looks out onto something (albeit a shadow-puppet version of a window), but the presence of the projector casting that light continues to remind us that the wall is a solid plane and the window is an illusion.

Wannabe (1991) is, if anything, a simpler affair. A spotlight in the ceiling presents viewers with a choice of how to behave in its presence: to step into the charmed circle, shun it altogether, or hover on the sidelines. These were choices Eliasson would soon be facing himself, “in real life,” as his own career took flight. What propelled his work from art-student cleverness to international standing was its ability to connect with profound human feelings. The Tate curator Mark Godfrey writes in the exhibition catalog:

In response to rampant capitalism, he felt it all the more urgent to reclaim wonder and beauty from commerce and, against the multicoloured techno-spectacles we find in urban shopping centres, to make a rainbow with little more than a punctured hosepipe and a spotlight.

Yet the most striking quality of Beauty (1993), the rainbow to which Godfrey refers, has less to do with light than with silence. The installation does indeed consist of a punctured hosepipe and a spotlight, ranged along the ceiling of a black-painted room to create a miniature shower of what the late German writer and poet Werner Bergengruen has called “drops lit up in color”: an ever-shifting rainbow mist. But a softly padded floor means that the only sound we hear inside that room is made by water, gently falling in perfect tranquility.

Another remarkable early work is Moss Wall (1994), a gigantic sheet of living Arctic moss, a lichen with a spongy, springy texture and a penetrating, herbal smell, durable enough for visitors to touch, a tapestry that continues to maintain its independent existence as an outpost of nature in the midst of art.

From the beginning, however, Eliasson’s search for simplicity always coexisted with an equal obsession with complex geometries, from the five regular polyhedra—the figures that fascinated both the ancient Greeks and the artists of the European Renaissance—to forms only truly imaginable in the computer age, such as fivefold symmetry and fractals, to the fathomless complexities of nature. For decades, he has photographed Iceland’s glaciers, volcanoes, coastlines, and natural marvels that defy classification, watching with dread as the familiar contours of his island, and our world, melt away with climate change. When The weather project went up in the Turbine Hall in 2003, the planet was already heating perceptibly, but the cascade of warming effects that troubles the Arctic’s fragile balance was nowhere near as tangible then as it is today.

To focus public attention on the present unfolding tragedy, Eliasson has created Ice Watch, blocks of eerily blue Greenland ice set out to melt, first in Copenhagen’s City Hall Square in October 2014, when the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued its fifth report; then in the Place du Panthéon in Paris for the UN Climate Conference of December 2015; and in London this past December as a prelude to his Tate retrospective. The installation brings a miniature version of Greenland’s catastrophic melt close enough to touch, and movingly, a photograph in Experience shows a woman in Paris huddled in the melting center of a block, hugging its frozen surface for dear life.

Model Room, the cabinet of wonders that opens the Tate exhibition, is a glass vitrine stuffed with models for Eliasson’s infinite variety of projects, in every medium and state of completion: folded paper, glass, stone, metal, and ceramic suggesting forms transparent, opaque, streamlined, and spiky—embodied thoughts that seem to have issued from the brain of Plato, or Leonardo, or some surreal space program. The assemblage gathered for Model Room stops in 2003, a watershed year for the artist’s career; in addition to installing The weather project in London, he represented Denmark in the Venice Biennale and mounted two other ambitious personal exhibitions, at the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid and the Kunstbau at the Lenbachhaus in Munich.

Advertisement

By this time, Eliasson’s work had turned into an intricate network of collaborations, with people to help him carry out his designs, refine his ideas, deal with logistics, or simply teach him what he wanted to know. In 2008 he moved his studio into a four-story brewery building, with five separate teams concentrating on design and production, research and communication, finance, exhibition planning, and design and architecture, and a communal lunch to bring them all together. He says in Experience that he is most present at the beginning and the end of a project, but he still carries the flame of a hands-on artist.

A set of recent watercolors on display last September–December in the Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in Los Angeles showed a sure, delicate touch in detailing color shifts through a series of elliptical forms—the twelve-year-old painter of troll faces has evolved, after forty years, into a painter who can invest abstract figures with literally colorful personalities. Another set of recent watercolors at Tanya Bonakdar resulted from an unusual collaboration: Eliasson and ice. The artist set small blocks of glacier ice on pigment over watercolor paper and let the melt-generated patterns flow freely. Two other paintings in this Glacial Currents series share space in the Tate exhibition with The Presence of Absence Pavilion (2019): a large bronze, cast in an oblong mold around a core of Greenland ice that melted away in the process. The empty space left by the receding ice is an ominously present absence: the reminder of similar events that are happening all over this warming globe.

The Tate show is effectively split by Din Blinde Passager (Your Blind Passenger; 2010), a long tunnel filled with dense colored fog that reduces visibility to about a meter. Some people find their way through the thick atmosphere by maintaining contact with a wall. Some proceed on tentative tiptoe, some forge ahead blindly, overshooting the limits of their own vision, which is by far the most fun—many of these more recent works suggest that parenthood has brought out the playful aspects of the artist’s nature. The fog begins in the intense shade of monofrequency yellow that has almost become Eliasson’s signature, but after a while the eye, a little bored with the monotony, begins to play tricks on itself in complementary purple. Closing your eyes while striding forth is the most fun of all, because blinking brings not darkness, but intense purple light. Eventually, the pervasive yellow gives way to the whitish color of dawn, and in turn dawn gives way to sky blue, the colors of normality that signal the approach of the exit door.

There seems to be a parent’s touch as well in the outdoor Waterfall (2019) that splashes merrily on the Tate’s grounds, a jerry-built affair of pipes and metal girders that calls attention to its artificiality even as it spills out one of nature’s most reliable marvels: cascading water. On a sunny day the droplets fall like tiny diamonds, and the fountain is a magnet for toddlers, who scream with delight at the noise and the colossal puddle that forms around the waterfall’s base.

From the beginning of his career, Eliasson’s fascination with geometry drew inspiration from the Icelandic architect-mathematician Einar Thorsteinn (1942–2015), who eventually became part of his studio. There are evident echoes of the geometric drawings of Renaissance artists like Leonardo and Piero della Francesca, and the finished works have an unmistakably Platonic feel to them. Huge spheres of glass or metal like Stardust Particle (2014) or faceted kaleidoscopes like Your Planetary Window (2019) exist both as objects in their own right and as cast reflections on, or of, their surroundings. In a famous passage from Plato’s Republic, Socrates compares normal human existence to a group of prisoners shackled in a cave who have never seen anything but flickering shadows of figures cast by a fire on the cavern wall, and asks:

If one of these people were suddenly released from bondage and forced to stand up, turn his head around, and walk out to look at the light, wouldn’t doing all these things be painful, and wouldn’t the glare make it impossible to see what had been visible in the shadows?… And if someone dragged him into the light of the sun, wouldn’t he suffer and complain about being dragged, and when he emerged into the light, with his eyes full of sunshine, wouldn’t he have trouble seeing a single thing that we regard as real?

One of Olafur Eliasson’s most salient tricks is to fill our eyes with sunshine.

How do works of art emerge from a studio that numbers around one hundred people? Five hundred years ago, Raphael ran what sounds like a similar industrial-strength operation, gathering a crowd of eager young people and older sages to help him explore the far reaches of what one word, disegno, “design,” might possibly mean, from God’s plan for human salvation to the contents of a sketchbook, firing the imaginations of everyone around him with his incandescent visions. Thanks to his energy, his perceptiveness, and his uncanny talent, the workshop throve under his direction; the greatest rebel against its strictures, Giulio Romano, was also, not surprisingly, the workshop’s most gifted participant, to whom Raphael, typically, granted immense responsibility.

Perpetually curious and phenomenally energetic, Eliasson has surrounded himself with cooks, scientists, and architects as well as artists, mechanics, and craftspeople, in the belief that every kind of human endeavor feeds into every other. For the duration of his exhibition, the café in the new Blavatnik wing of Tate Modern is serving vegetarian recipes from his own kitchen, prepared with minimum addition of CO2 to the earth’s already saturated atmosphere and served in the studio’s communal spirit. The Eliasson Studio has even published its own cookbook, Studio Olafur Eliasson: The Kitchen, with recipes calibrated for feeding a family or an army. The Tate’s café has been hung with Eliasson’s driftwood mobiles, all pointing in one direction: magnetic north.

The catalog that accompanies “In Real Life,” like Experience, contains a single essay about the artist’s work; the rest consists of his interviews with people who have inspired him, from the Danish chef René Redzepi to the climate activist Mary Robinson. His own language is clear and straightforward, and his partners in conversation respond in kind. The book is designed to take Eliasson’s art beyond the confines of the exhibition, and it becomes yet another extension of his perpetual curiosity, as well as a revealing image of his extroverted, inclusive idea of what art and artistry can be.

Great success has also brought great challenges. Eliasson has demonstrated his commitment to bridging the world’s gap between rich and poor with projects like Little Sun and Green light. Little Sun, unveiled at the Venice Architecture Biennale of 2012, is a solar-powered lamp that casts a particularly bright light and lasts for several hours, so that children without access to electricity can study at night. The lamp, in the shape of a yellow sunflower (and now in a smaller version that looks like a diamond), sells for a high price in the developed world so that it can be sold in developing nations for a fraction of that amount. Green light, shown at the Venice Biennale of 2017, provided a studio space where the refugees who have flocked to Italy could assemble light fixtures from recycled materials as they conversed with one another and with the public. In the same spirit, the Tate exhibition features a huge table of white Lego blocks so that people can build their visions of an ideal city. On the other hand, this onetime critic of capitalist spectacle has also created installations for the likes of the Fondation Louis Vuitton and BMW, and designed his first building for Kirk Kapital, a holding and investment company.

Despite all the difficulties and inconsistencies that surround an artist of such dauntingly public resonance, Eliasson continues to pierce through to the heart, of things and of the people who experience his work. His mobiles of driftwood and metal almost always contain a lodestone, to ensure that they point faithfully north. They inspire a similar confidence in the good faith of their creator, who knows how much childish fun there is in watching an errant fan swinging wildly from its cord like a rogue pendulum (Ventilator, 1997). What could be simpler than a lighted candle standing upright on a round mirror? This installation, I grew up in solitude and silence (1991), could be any one of us, burning with our private hopes and passions, and yet all around the silver circle we can see the reflections of the outside world, other people, and, in the candle’s mirror image, the steadfast support of a kindred soul. For the Venice Architecture Biennale of 2012, “Common Ground,” Eliasson fixed two Little Suns to a fan in a dark room, so that the pair of whirling lamps created a single ring of light, the Milky Way of their own miniature universe.

This Issue

September 26, 2019

Australia’s Shame

Brexit: Fools Rush Out

‘Ulysses’ on Trial