1.

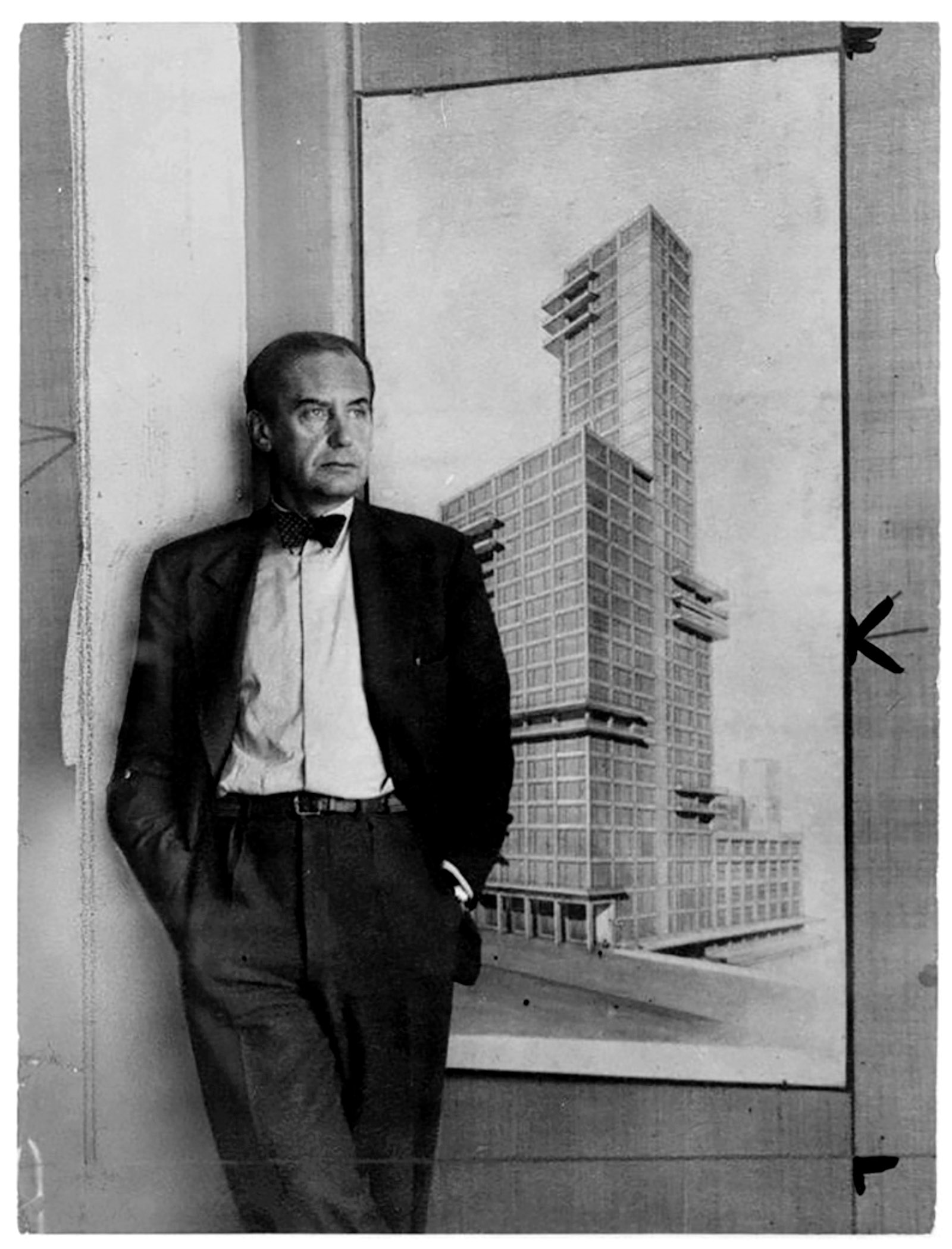

Whatever else one might think of Walter Gropius—the pioneering German architect who founded the Bauhaus a century ago this year and thereby earned an irrevocable place in the pantheon of Modernism—it is hard not to be impressed by his most salient talent: survival. He escaped misfortunes that included being buried alive for three days while a front-line officer in World War I; the narcissistic manipulations of his first wife, Alma Mahler; the barbarism of Hitler, which imperiled his more sympathetic second wife, who was Jewish, and forced the couple to flee their homeland; the philistine indifference to Modernism in interwar Britain, their first refuge from Germany; and the intrigues of academic politics that repeatedly enmeshed him. Yet after each new somersault of fate he somehow landed on his feet and emerged undeterred.

Gropius died half a century ago this summer at age eighty-six, six weeks before the somewhat younger Ludwig Mies van der Rohe; both were posthumously hailed as among the foremost architects of the age. Before World War I, they had worked together as assistants in the Berlin atelier of the master builder and industrial designer Peter Behrens, where another employee around that time was the twenty-something Le Corbusier. Mies would go on to become the last of the Bauhaus’s three directors and, like its first, enjoy a highly successful late career in the United States.

But in notable contrast to Mies—whose bare-bones, steel-frame, glass-curtain-wall formula provided the basic template for postwar high-rise construction worldwide—Gropius’s longest-lasting impact came from the innovative pedagogical principles he championed as head of the most influential art school since the École des Beaux-Arts was established in Paris more than two and a half centuries earlier.1 The architectural historian Bernard Michael Boyle has summarized this revolutionary repositioning of design education:

Gropius came to the Bauhaus from a career in architecture, and in fact he viewed all design as architectonic in basic character. With this understanding, Gropius approached all design problems as basically similar, and thus considered it necessary for all designers to have the same basic education…. Gropius’s modern architectonic art included all artistic activity as well as all design problems: “What the Bauhaus preached in practice was the common citizenship of all forms of creative work, and their logical interdependence on one another in the modern world”; and the educational program was intended to remove the academic distinction between the so-called fine arts and the so-called applied arts or crafts.

Two of Gropius’s early German buildings still regularly appear in architectural history surveys: his and Adolf Meyer’s Fagus shoe factory of 1911–1913 in Alfeld (which drew on humble vernacular industrial forms but raised them to the level of high art) and his Bauhaus of 1925–1926 in Dessau (a work of propagandistic genius with which Gropius did for the Modern Movement roughly what Bernini had done for Counter-Reformation Catholicism). At the Bauhaus, Gropius was an ideal administrator, with his calm but firm personal demeanor and intentionally conventional affect: he dressed not like a bohemian but like a bank manager, in striped pants, black coat, white shirt, and bowtie.

This protective coloration allowed him to act as a buffer between suspicious local authorities who grudgingly financed this unprecedented educational experiment and the avant-garde artists he employed as instructors, whom conservative commentators considered degenerate madmen. Simultaneously, at his new laboratory for artistic exploration, Gropius acted as a veritable lion tamer who kept the supremely gifted but eccentric faculty in line, while allowing them and their eager young charges maximum creative freedom.

It was a balancing act of extraordinary deftness that only someone with strong self-discipline and steely ambition could pull off. Yet history has not dealt kindly with Gropius, especially after Tom Wolfe’s ignorant anti-Modernist diatribe From Bauhaus to Our House (1981), which mercilessly lampooned him as the chief perpetrator of a hopelessly inhumane mode of architecture and an insufferable prig to boot. Wolfe was certainly not alone in his ad hominem animus. The architectural historian Joseph Rykwert has described Gropius “as a man [who] seemed to have fewer redeeming features than many of his kind…. His pinched humourless egotism was unrelieved by sparkle.” That assessment is supported by the critic Brian O’Doherty’s interview with Gropius for Boston public television during the early 1960s (available on YouTube), in which the charming young host’s suave blandishments contrast starkly with the gruff responses of this dour-looking, near-octogenarian head of a worthy but unexciting New England architectural office with a specialty in school design.

The British art and design historian Fiona MacCarthy met the architect in the late 1960s, was deeply impressed, and has admired him ever since. In Gropius: The Man Who Built the Bauhaus, she valiantly attempts to elevate his professional reputation as well as rehabilitate his personal image. Yet try as she might, he fails to come alive, either as a captivating personality or as a creative force. What stands out most clearly is his undeniable proficiency as a promoter—of himself, of the Bauhaus, of the cause of Modernism in general, but a promoter nonetheless.

Advertisement

Despite her advocacy, MacCarthy does not suppress her sharp insight into why Gropius is now accorded comparatively lower status among the titans of his profession and offers a convincing explanation for the strange but unmistakable lack of character that plagues so many of his otherwise expertly conceived buildings:

The working methods he first evolved with Adolf Meyer amounted more or less to the modus operandi that Gropius developed into a philosophy. This was a slow process of Gropius outlining his ideas for Meyer to interpret on the drawing board, a toing and froing of creative input that would form the basis of Gropius’s evolving theories of architectural co-partnership. The sharing out of responsibilities is arguably the reason why Gropius’s buildings lack the sometimes transcendent personal qualities of architecture by his contemporaries Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe.

2.

Walter Adolph Georg Gropius was born in 1883 to an upper-bourgeois Protestant Berlin family, the son of a civic building official and an artistically inclined mother. As the historian Peter Gay noted, the young Walter “had Kultur in his bones.” His great-uncle was the eminent architect Martin Gropius, the codesigner of the city’s Applied Arts Museum of 1877–1881, an imposing neo-Renaissance structure now used as a kunsthalle and known as the Martin-Gropius-Bau. During young Walter’s classics-oriented secondary education, he became fascinated by Julius Caesar’s detailed description of one of the wooden bridges he ordered built for Roman troops to cross the Rhine, and made a scale model of it. Just before he turned twenty he entered the Technical University of Munich but was soon called up for compulsory military service, after which he resumed his studies at Berlin’s Royal Technical University.

The aspiring architect got some early practical experience by erecting farm structures on an uncle’s estate in the German (now Polish) province of Pomerania and designing a country house in the vicinity for family friends. Interestingly for a future educator, he never finished his university studies and took off instead for a Wanderjahr in Spain. Upon his return to Berlin, he joined the Behrens firm but left it in 1910 to set up an independent office with Meyer as his assistant. The other momentous event for Gropius that year was meeting Alma Mahler, the wife of the renowned Austrian composer and conductor.

At thirty, Alma was already considered the femme fatale of the Vienna art world because of her many heartbroken suitors. She began a flirtation with the four-years-younger Gropius while her worshipful husband was mortally ill with the heart ailment that would kill him several months later. The architect’s tempestuous five-year courtship of Alma was interrupted by her amour fou affair with the Expressionist artist Oskar Kokoschka, who, after she dumped him, commissioned a Munich doll maker to create a life-size sex doll made in her image, which he photographed and painted several portraits of before he destroyed it in a drunken rage several years later.

Despite her premonitions of doom—she wrote of Gropius that “this person is not what my life is about” and “he is just tepid, and I am not—that will never work”—they wed in 1915. During their miserable five-year marriage, she gave birth to their daughter, Manon (whom Alma vengefully did everything possible to keep away from her adoring father), and a son, Martin, named after Gropius’s famous relative. Unfortunately, everyone in Vienna except Gropius was sure that the boy had been sired not by him but by Alma’s latest lover, the writer Franz Werfel. The hydrocephalic Martin died in less than a year, the couple divorced in 1920, and Alma married Werfel nine years later.

Gropius had better luck with his second wife, whom he wed in 1923 and stayed with for the rest of his life. Fourteen years his junior, she was born Ilse Frank, but he more poetically called her Ise. If Alma was the prototype of the modern celebrity-seeker, then Ise was the traditional wifely flame-keeper, an exemplar of the protective, nurturing, self-sacrificing artist’s helpmeet who served at once as muse and advocate. She also became Gropius’s indispensable public relations agent, a new but crucial task prompted by the twentieth century’s rapidly changing modes of mass communication.

The couple, although devoted to each other, abjured middle-class notions of conjugal fidelity, and each pursued extramarital dalliances. But they also established a warm and mutually supportive home life, strengthened when in 1936 they adopted Ise’s ten-year-old orphaned niece, Beate—known as Ati—who in effect was the substitute for Manon, who had died of polio the year before at age eighteen. (Ati Gropius became an accomplished graphic designer and married the American Brutalist architect John Johansen, an early student of her adoptive father’s at Harvard.)

Advertisement

Gropius’s hopes for a thriving architectural practice in England—where in 1934 he partnered with the younger British architect Maxwell Fry—resulted in the execution of only two houses in London and a much-praised village school in Cambridgeshire. The frustrated émigré quickly comprehended that he would not have the same opportunities to build there that he did in Germany and began to think about resettling in the United States, which was more hospitable to the new architecture and its foreign-born practitioners. Encouraged by the successful transition to America of his old Bauhaus colleagues Josef and Anni Albers, who for three years had been teaching at North Carolina’s Black Mountain College—the closest thing to the Bauhaus that has ever existed in this country—in 1936 he accepted the offer to become chair of the architecture department at the newly created Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD).

MacCarthy’s tendency to take Gropius’s side in virtually every conflict is least justifiable in her depiction of his fraught relationship with Joseph Hudnut, the first dean of the GSD and the man who made possible the most important affiliation of the architect’s American period. What Hudnut did not anticipate when he offered Gropius the job was the exile’s determination to replicate the Bauhaus curriculum in Cambridge—a wholly unrealistic agenda for the GSD, which is a professional architecture school, not an arts-and-crafts academy, and required far more complex offerings than the back-to-basics Bauhaus Vorkurs (preliminary course) that remained Gropius’s persistent obsession.

Nor did Hudnut foresee the extent to which the man whose career he saved was from first to last an arch-opportunist who would attempt to undermine his superior’s authority and usurp his position at every turn, especially when it came to his fixation on the Vorkurs. Never mind that Hudnut went along with Gropius’s urging that he employ several of his old European colleagues, including his star Bauhaus student Marcel Breuer and the city planner Martin Wagner—eminently qualified professionals to be sure, but a considerable Bauhaus reunion nonetheless. The dean’s feelings of betrayal are not difficult to fathom. Furthermore, Hudnut was far from the “fuddy-duddy” that MacCarthy alleges him to have been. No less a maverick than Frank Gehry, who briefly studied city planning at Harvard during the mid-1950s, has spoken appreciatively about Hudnut’s taking his classes on field trips to local buildings that he particularly esteemed, a strikingly hands-on departure from the GSD’s sometimes overly intellectualized approach to architecture.

Oblivious to the fact that he had lost his battle with the well-connected Hudnut, Gropius was dumbfounded when in 1948 Harvard’s president, James B. Conant, informed him that he would be retired the following year, contrary to the architect’s assumption that he possessed lifetime tenure. He got a four-year reprieve by pleading poverty, but after budget cuts possibly intended to speed his exit, he quit in disgust in 1952 and returned to full-time architectural practice.2

3.

Apart from Harvard, the defining factor in Gropius’s late career was his nearly quarter-century association with the Architects Collaborative (TAC), the Cambridge-based cooperative started in 1945 by eight partners—four of them husband-and-wife practitioners. Gropius, more than three decades older than them all, was recruited as primus inter pares. The firm’s generalized name presaged the now-prevalent tendency for high-style architectural offices to devise a separate corporate identity that does not derive from the names of the principals, as did McKim, Mead & White or Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). However, just as present-day clients reflexively think, for example, of Rem Koolhaas rather than his Office for Metropolitan Architecture, so most potential patrons of TAC identified it with Gropius, which is doubtless just as the partners intended.

Today Gropius’s generously collegial approach is more valued than ever as an early departure from the long-dominant Great Man conception of architecture as the product of a single creative figure. TAC is now seen as a precursor of the current trend toward nonhierarchical and gender-equal architectural practice. (A quarter of its founding partners were women, a remarkable ratio for that time.) However, in recent decades the growing insistence on a more egalitarian architectural workplace has superseded the TAC model, most conspicuously at the Oslo-based firm Snøhetta, which since its founding in 1989 has applied a team methodology throughout the entire design development process and has moved well beyond TAC’s formula of having individual partners draw up schemes that were then presented to the entire office for group critique and modification.3 (MacCarthy is mistaken in claiming that TAC was ever “the largest architecture practice in America,” a distinction held throughout TAC’s fifty-year existence by SOM, which in 1952 had a thousand employees.)

TAC’s most prestigious early project—a direct result of Gropius’s academic affiliation—was the Harvard Graduate Center of 1948–1950. But this bland assemblage of five mid-rise International Style residence halls, the first example of modern architecture on the university’s campus and now officially known as the Gropius Complex, barely ascends to the quality of even middling postwar American university architecture. It comes nowhere close to his crisp and dynamic Siemensstadt workers housing of 1929–1931 in Berlin. Today, the main interest of TAC’s Harvard buildings derives from their site-specific artworks, which Gropius commissioned from his friends the Alberses, Jean Arp, Herbert Bayer, Joan Miró, and Richard Lippold—a remarkable array of talent for such a relatively small project.

Maquettes for them were included in “The Bauhaus and Harvard,” a rich and instructive exhibition of almost two hundred pieces by more than seventy artists, almost entirely from the Busch-Reisinger Museum in Cambridge—the biggest Bauhaus collection outside Germany—which was on view earlier this year at the Harvard Art Museums. It focused on works in a wide variety of mediums by artists associated with Gropius at the Bauhaus (among them Marianne Brandt, Marcel Breuer, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, Oskar Schlemmer, and Gunta Stölzl), as well as by students who trained at the Bauhaus or at the GSD. Harvard’s extraordinary postwar commitment to design was signified by two rare surviving examples of the plaid cotton bedspreads that Anni Albers created for the new dormitories.

Another high-profile TAC commission that derived from Gropius’s star status was the American embassy of 1959–1961 in Athens, part of the US State Department’s idealistic postwar initiative to engage this country’s most talented architects to represent America abroad. Regrettably, the scheme for the Greek capital—a rectangular white-marble-clad, colonnaded structure with a flat projecting roof—brings to mind not its intended local model, the Parthenon, but instead the lookalike shoebox pavilions being cranked out at that time by Edward Durell Stone and Minoru Yamasaki.

TAC’s one offbeat touch was to position the Great Seal of the United States in the second of the street façade’s nine bays rather than the central one, perhaps a belated nod to the Bauhaus preference for asymmetry but scarcely a provocative gesture. Kitschy though Stone’s US embassy of 1956–1959 in the Indian capital of New Delhi might now seem—with its pierced wraparound jali screens more evocative of Miami Beach than the Mughals—it is at least an entertaining exercise in midcentury American architectural statecraft (and stagecraft), unlike TAC’s turgid Athenian composition.

The most visible and dubious project of Gropius’s late career was the Pan Am Building of 1958–1963 in New York, a fifty-nine-story Brutalist skyscraper he created with Pietro Belluschi (then dean of architecture at MIT) and the firm of Emery Roth & Sons. Named for its major tenant—Pan American World Airways, at that time the largest international air carrier—this 2.8-million-square-foot structure with a flattened octagonal footprint looms athwart Park Avenue. Its vast bulk blocks vistas uptown and downtown that previously had been interrupted only by the picturesque and lower New York Central Building of 1927–1929 by Warren & Wetmore, the same firm that created the glorious Grand Central Terminal of 1903–1913, just south of the Pan Am Building.

No less pronounced than its claustrophobic effect on the surrounding streetscape—quite a feat in densely built-up Manhattan—is the plethora of individually defined windows: nearly eight thousand of them, framed by thick mullions, on the forty-five-story shaft that rises above the fourteen-story base. No wonder this busy façade was instantly likened to an upended IBM keypunch card. Although a 1987 New York magazine poll named the Pan Am Building the structure that city residents would most like to see demolished, a new generation of architecture aficionados has been more accepting of the long-despised Brutalist style, which inarguably conveys a solidity lacking in the currently fashionable biomorphism known as blobitecture.4 Thus MacCarthy is likely not alone in her enthusiasm for this behemoth, which she lauds as Gropius’s “most resplendent postwar building.”

The increasing sclerosis that set into Gropius’s late work is illustrated by contrasting the very finest of all his buildings, the Bauhaus in Dessau, with his far less satisfactory Bauhaus Archive of 1964–1979 in Berlin. As opposed to most of Gropius’s oeuvre, the Bauhaus building—actually a conjoined complex of three wings organized in a rectangular pinwheel pattern—is at once propulsive and disciplined. Each increment of the flat-roofed, tripartite composition is different from the other two. The art studio/workshop segment is clad in a glass curtain wall, although one gray stucco corner is emblazoned with the institution’s name spelled out vertically in projecting sans serif white letters designed by Bayer. (However, the Bauhaus does not have “prefabricated concrete walls,” as MacCarthy writes; the structure’s reinforced concrete framework was poured on site.)

The six-story dormitory wing, a bit taller than the others, is surfaced in white stucco, with each dwelling unit sporting its own small balcony. Both the classroom wing and the two-story office bridge that links the entire ensemble are wrapped in the continuous, horizontal ribbon windows that Le Corbusier deemed essential elements in his canonical “Five Points of Modern Architecture.” Gropius’s composition looks markedly different from every angle as one walks around it, and yet its diverse and asymmetrical elements always complement each other so harmoniously that one forgets the tenet of Beaux-Arts architecture that bilateral symmetry is the wellspring of all beauty.

That is not at all the case with Gropius’s Bauhaus Archive, the building that he designed to memorialize his greatest achievement and that was only completed in 1979, a decade after his death, by his former TAC colleague Alex Cvijanovic and the Berlin architect Hans Bandel. Many alterations to Gropius’s original scheme had to be made before it was realized, but his primary organizational motif—two parallel rows of white-walled, windowless galleries surmounted by half-barrel-vaulted skylights in a rounded sawtooth pattern—was executed largely as he had envisioned it. Stiff and frontal where the original Bauhaus was loose and multidirectional, the Berlin depository sums up what went wrong with its principal designer’s career.

Gropius’s death neatly coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of the Bauhaus, as well as the 1969 publication of Hans Maria Wingler’s monumental monograph Bauhaus: Weimar, Dessau, Berlin, Chicago, which has now been reissued in its original slipcased, near-folio-sized format to mark the school’s centennial.5 This physically commanding but critically uninformative tome is primarily useful for its complete roster of the school’s matriculants, a coterie often as inflated as the purported passenger list of the Mayflower. But even after a century, the undimmed glamour of the Bauhaus makes it understandable why so many people in the heyday of Modernism wished they had been aboard it, too.

This Issue

September 26, 2019

Australia’s Shame

Brexit: Fools Rush Out

‘Ulysses’ on Trial

-

1

See my “The Powerhouse of the New,” The New York Review, June 24, 2010. ↩

-

2

A far more evenhanded analysis of the Gropius–Hudnut tug-of-war can be found in the architectural historian Anthony Alofsin’s authoritative study The Struggle for Modernism: Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and City Planning at Harvard (Norton, 2002). ↩

-

3

See my “The Risk of Being Too Nice,” The New York Review, February 7, 2013. ↩

-

4

See my “The Brutal Dreams That Came True,” The New York Review, December 22, 2016. ↩

-

5

See Peter Lloyd Jones’s review of the original, The New York Review, January 1, 1970. ↩