Nelson Algren arrived in Hollywood on January 26, 1955. He had spent the previous year rewriting a book he couldn’t stomach and running from a wife he didn’t love. He was agonized by the State Department’s refusal to issue him a passport—they distrusted his leftist political views—and he had wandered from state to state, from bus stop to cheap motel, desperate to find a place where he might be at peace to write the way he wanted to. He knew Hollywood was no place for authors of distinction but couldn’t argue with a thousand a week. He was soon in the company of the Austro-Hungarian director Otto Preminger, who had bought the rights to his novel The Man with the Golden Arm (1949) and wanted him to write the screenplay. Bringing Algren down Wilshire Boulevard in his red Cadillac, Preminger chose the worst first question to ask his new collaborator. (He just wasn’t sure where to begin with Chicago’s answer to Dostoevsky.) “How come you know such terrible people you write about?” he asked.

People who expect contempt can spot it at five hundred yards. Within a few days, Algren had written a film treatment full of compassion for the prostitutes, junkies, Polish immigrants, and workers in his novel, and Preminger threw it in the trash. “He had showed what he thought of me and my people,” Algren later said, “and I showed him what I thought of him and his people.” He did this by refusing to write the screenplay Preminger expected. From first to last, Algren was an author who hated schlock, who avoided happy endings and disdained binary narratives about good and evil, and the film that eventually emerged, starring Frank Sinatra, made his blood run cold.

Algren’s conscience was trailed by the FBI. The reasons weren’t very complicated. He was a writer out of the Depression who felt that America should be judged by how it treated its poorest citizens. As an artist, he had a special vision and a singular prose, and he used them to see behind the billboards and the newsreels, beyond the lipstick, beyond the fear, into the lives of people left stranded by the American dream. He offers a lesson in what it means to be a writer in a society that believes commerce is virtue. More than Walt Whitman or John Steinbeck, more than F. Scott Fitzgerald or Dorothy Parker, he reveals the essential loneliness of the serious writer, never fooling himself with baubles and status, but staying with his subjects, the forgotten in society and his own alien self. All great writers are self-harmers—they have to be, if they’re doing it right—and Algren lived the second half of his life in a miasma of chaos and disappointment, having failed some test of worldliness. But with Colin Asher’s brilliant new biography, Never a Lovely So Real, and Algren’s major books back in print, his time has arrived. Amid the alarm bells of 2019, when immigrants and the poor are under attack, we find the humane lights of a forgotten writer shining for a new audience.

“Our practice of specializing our lives to let each man be his own department,” he wrote in his book-length essay Nonconformity,

safe from the beetles and the rain, is what is really meant by “a professional, artistic point of view.” For it is not a point of view at all, but only a camouflaged hope that each man may be an island sufficient to himself. Thus may one avoid being brushed, even perhaps bruised, by the people who live on that shabby back street where nearly all humanity now lives.

A view that betrays an uneasy dread of other men’s lives; a terror, bone-deep yet unadmitted, of the living moment.

There’s a certain weight on the word “lives”: writers always have a problem to face, about how people live and how they will be represented in their pages. It’s a nineteenth-century kind of problem, in the sense that Victorian writers, the better ones, never stopped thinking about it, and often made masterpieces from the challenges of what makes a society, and what makes a person. This requires a writer to go outside occasionally and perhaps to visit a factory, a prison, a bar, or a street corner. American letters is full of democratic vistas and their manifold constraints, but the great and original voices, from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Toni Morrison, rise from the plains of want and perdition to demonstrate the truths of human interaction. Algren goes far. He shows the lowest in society fighting the biggest odds for the smallest rewards, but he raises them all—pimp, junky, and bellhop—into standards of American reality.

As a young man, Algren saw fear in a swirl of dust. Disliked by his mother and sometimes distant from his father, he was born in 1909 and ended up on Chicago’s North Side. In time, he turned his back on the family garage business and took up with Marcus Aurelius. He graduated from the University of Illinois with a degree in journalism and started hopping boxcars to the South, spending a full year and a half looking for work, odd-jobbing at carnivals for hot dogs and beer, seeing emptiness all around and a rising tide of vagrancy. “By the winter of 1933,” writes Asher,

Advertisement

he had become convinced the meritocratic ideal was a fraud, that everyone who placed their faith in it had been fooled, and that he was obliged to reveal that deception. “Everything I’d been told was wrong,” he said. “…I’d been assured that it was a strive-and-succeed world…. But this was not what America was. America was not socialized and I resented very deeply that I’d been lied to.”

Through a publication called The Anvil, he got involved in the proletarian literature movement. He joined the Communist Party—to “fight Fascism,” as they say, but also for the prestige—and published work in Story magazine, which drew the attention of a New York publisher. But he still lived like a drifter as he dreamed about the book he was writing. After hopping another freight train and landing in Alpine, Texas, he stole a typewriter and ended up in jail.

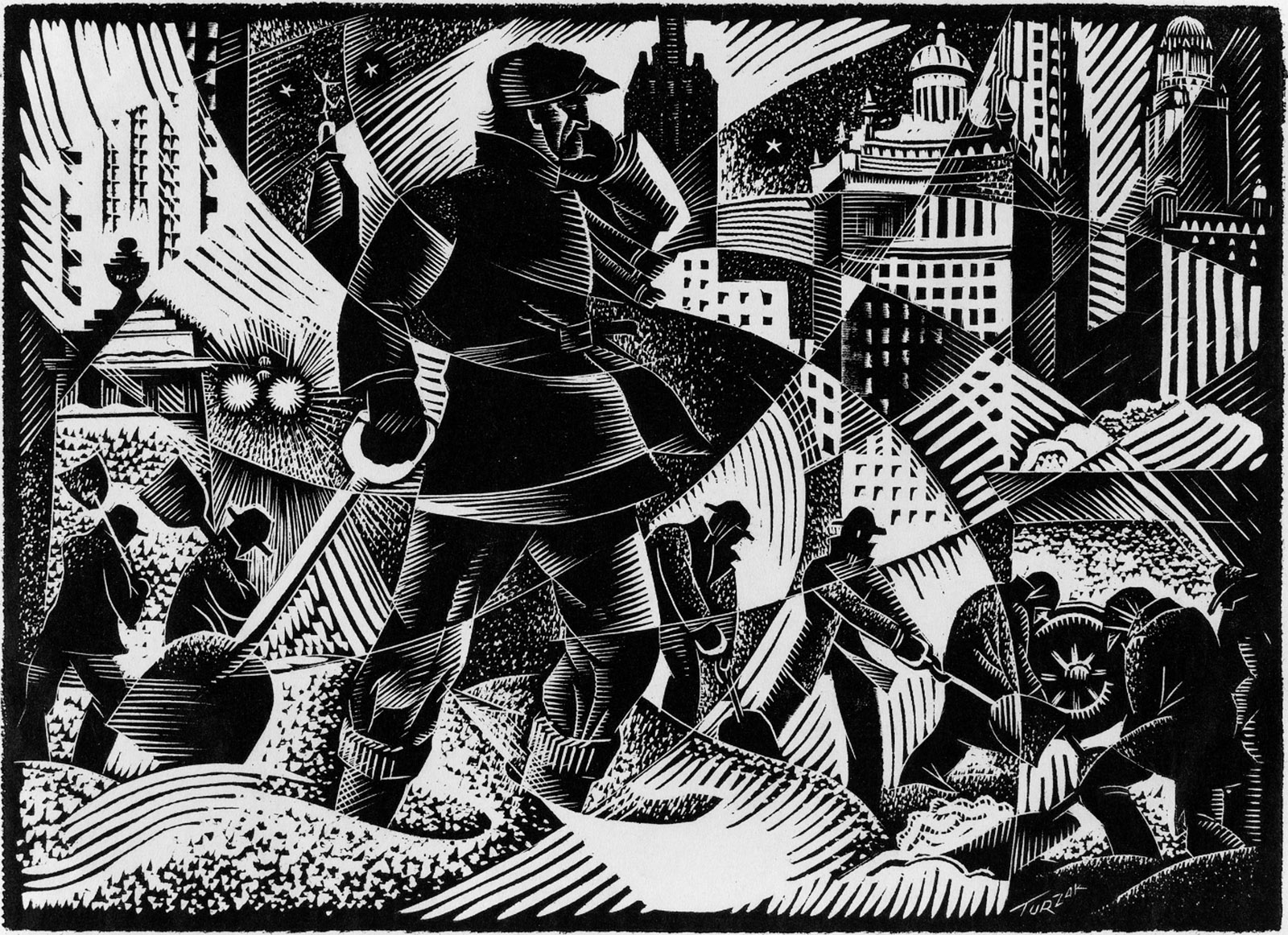

Back in Chicago, “he visited brothels and flophouses, walked through the parks, listened to barkers calling outside dime burlesques.” He moved into two rooms on West Evergreen Avenue, ground zero of Polish Chicago, with the tracks of the El at the end of his block, and he got down to work. In his years with the John Reed Club and the various proletarian writers’ magazines and projects, he had been carving out a place of supreme separation, a place from which to imagine. He had encouraged his friend and fellow Chicago writer Richard Wright, and given him a title, Native Son. When Wright’s book came out, it was a sensation and encouraged Algren to dig deep. The challenge for him was to find sentences in the neon wilderness outside his window, filled with the shadows and manipulations you get out there, the dependencies and the emotion and the testosterone. It was night-time in America, and nobody had really walked those new streets before. How does a novelist bring grace and beauty to the handling of brutality and ugliness?

Somebody in Boots (1935) was Algren’s first novel, the one he was reworking into A Walk on the Wild Side the year he fell foul of Hollywood, but the book that really shows the Algren style in its first great flourishing is Never Come Morning (1942). It’s the story of Bruno “Lefty Biceps” Bicek, a seventeen-year-old boxer from those places around Chicago’s so-called Polish Triangle. Wearing charity clothes and filled with dread about fitting in, Bicek gets into a heist with a local thug named Casey and becomes dependent on the protection of Bonifacy the barber. Steffi, the boxer’s girlfriend, is raped by other boys with his “permission,” then he attacks one of them, a Greek, out of rage and hatred of his predicament. Bicek is caught in a spiral of crime and punishment, and so is Steffi, who ends up in a brothel, but the dream of redemption and of his success as a boxer and a life together never leaves them.

Every corner of the city and every corner of their minds—as well as their dialogue, the sounds they make—are alive in the sentences Algren was able to write. His words embody his people, they orchestrate and report on them, not only with a beautiful accuracy and a perfect rhythm of movement, but with the force of poetic myth. Not every biographer of a writer knows how to locate the source of his subject’s creative impulses, but Asher does. “The book makes no concessions to genre,” he writes of Never Come Morning, “and when it evokes clichés, it does so only to subvert them. Its locale suggests it will be a naturalistic novel, but its narrative voice is tender and personal instead of distant and coldly observed.”

So how did Algren get his style? “He is a philosopher of deprivation,” Donald Barthelme wrote, “a moral force of considerable dimensions and a wonderful user of the language.” The young Algren was excited by nineteenth-century Russian prose writers and motivated by people he met through The Anvil, edited by Jack Conroy, a man who became his mentor. Algren learned a great deal from those in the John Reed Society, from contributors to New Masses, and from members of the Communist Party, and he was moved by the fierce, art-as-weapon work being done by Herman Spector, Josephine Herbst, Mike Gold, and James T. Farrell—stalwarts of the movement and the struggle.

Advertisement

But his style rises, quite separately, from a moral acuity about the real substance of the United States. He caught it on the wind, the half-empty, half-bustling sound that blows through the stories of Jack London; the same one that whistles through the songs of Woody Guthrie and provides the grace notes in Fitzgerald, and he married that music to a sociological interest in the people of Chicago. For Algren, a tireless reporter’s job had to be done on the people he saw every day, but he didn’t stop there: he reimagined their world as poetic literature, a form of high-style witnessing. He liked to quote Conrad: “A novelist who would think himself of a superior essence to other men would miss the first condition of his calling.” That’s the Algren hallmark. He lived at the center of his material.

Given how naked his books are, how revealing, there was something terribly private about Algren. He kept his life to himself and simply watched the people he wrote about—a writer who “sees scarcely anyone except other writers,” he wrote, “is ready for New York”—and he often fell out with his friends. He never really forgave Simone de Beauvoir (with whom he had a long and torrid affair) for spilling the beans on their sex life in her novel The Mandarins (1954), which is dedicated to him. He just didn’t want publicity. He wanted sex and he wanted sales and he hated being hoodwinked over money, but he was always liable to suffer for the depth and constancy of his identification with the deprived, just as Fitzgerald suffered from too much identification with the swells. Kurt Vonnegut called him “the loneliest man I ever knew,” and the move toward exile—as for Samuel Beckett—was a natural-seeming one, kindling to the work if hard on the soul.

“No American author had written a novel about opiate addiction,” Asher writes,

and the subject was likely to turn readers off….[He] attached himself to [a] drummer from Arkansas and followed him through the city as he bounced between bars and cafés, looking for a dealer. The drummer’s quest stretched on into the small hours of the morning, and eventually Nelson became tired and irritable. I want to go home, he said. “Well, you don’t know what it’s like to have a monkey on your back,” the drummer snapped.

Then someone agreed to inject himself while Nelson observed and took notes.

Even today, The Man with the Golden Arm has enough vernacular energy to power Illinois. The story is of army veteran Frankie Machine and his dog-stealing friend Sparrow, their hoodlum world, their cunning dreams, working for Zero Schwiefka and his backroom poker game. The novel is lit through with particularly American anxieties about “making it”: every character is disabled by that need, by the need for one another, or for somebody he’s never met. Frankie’s addiction leads to murder and jail and broken promises everywhere, and seventy years later it feels familiar. American prisons are full of poor people like that with nowhere to go.

“Nelson Algren comes like a corvette or even a big destroyer when one of those things is what you need,” Hemingway said, “and need it badly and at once and for keeps.” He wrote inside his own copy of The Man with the Golden Arm, “OK, kid, you beat Dostoyevsky. I’ll never fight you in Chicago. Ever.” This was a time when every young male novelist—Norman Mailer, James Jones—wanted the big man’s imprimatur. It was Algren who got it, and he got it for making every sentence count and every comma speak. And yet a certain failure was written into the contract for Algren from the very beginning. Fame didn’t suit him, money was scarce, love left him lonely, and his publisher would eventually walk away from him, refusing to publish his excoriating essay Nonconformity, and later taking a pass on his novel A Walk on the Wild Side. He called himself “the tin whistle of American letters,” while knowing he was a “platinum saxophone.”

But anger and refusal can go a long way toward destroying a first-rate writer’s ability to function. The House Un-American Activities Committee fandango touched him personally: he was presented with a subpoena in 1955 and said he couldn’t afford to go to D.C. He then reached out to Doubleday, his publishers, hoping their lawyers might get it rescinded. “The fact that Nelson received this subpoena has never been widely reported,” Asher writes in a footnote, “mostly because he tried to hide it. He spoke about it on the record only once, in an interview with two student journalists.” Algren felt spied on, held back, denied, and undermined. It mortified him to be denied a passport, not least because it barred him from going to Paris to pursue his relationship with Beauvoir. He felt resistance from every other quarter. The New York intellectuals didn’t love him, and what they admired in E.M. Forster or Henry James they loathed in Nelson Algren: his social intelligence, the dark, organic wealth of his perception. His shirt collar was simply too frayed for the likes of Lionel Trilling. Algren countered with Zola and Chekhov. “The business of writers is not to accuse,” he quoted from the latter, “not to persecute, but to side even with the guilty, once they are condemned and suffer punishment.”

By the time he wrote A Walk on the Wild Side (1956), the mark was on him. It is Asher’s contention, reliably supported with new documents from Algren’s FBI file, that his career was ruined by J. Edgar Hoover as much as by Norman Podhoretz. In some ways, those two arch-critics and twentieth-century conformity-touts had a project in common—and Algren may have riled the FBI by placing the names of two horrible ex-Communist informers, Louis Budenz and Howard Rushmore, into the pages of The Man with the Golden Arm. But it was the reviewers who wore down his spirit. In The New York Times, Alfred Kazin accused him of “puerile sentimentality”; in The New Yorker, Podhoretz decried him for suggesting that “bums and tramps are better men than the preachers and the politicians.”

Yet the Podhoretz and Kazin position—that Algren’s stock-in-trade was to glorify prostitutes and vagrants at the expense of more respectable people—trashes a fundamental tenet of American literature. He didn’t glorify them, he included them, believing that a literature without them was insubstantial. “American writing,” Algren wrote, “will remain without vigor until it draws upon the enormous reservoir of sick, vindictive life that moves like an underground river beneath all our boulevards.” As late as 1990, nine years after Algren’s death, his work was being belittled by Thomas R. Edwards in these pages for being too political and too natural. “Social realism needs art, too,” Edwards wrote; “it needs to find formal and vocal ways of making its truth reasonably coherent.”

That’s how it rolls: if the characters are poor, it’s “social realism.” If their lives are described and their hardships revealed, it’s “merely real.” And if the writer of these books has not experienced every ounce of it himself, “he did not exactly live it.” Like earlier critics, Edwards was issuing political objections masquerading as literary judgments. The “unliterary” nature of Algren’s interests—the lowlife characters he so thoroughly pitied—put him on the wrong side of those who believe, not always without political motivations, that the job of literature is to elevate the reader. When Algren said he was a reporter, he was merely reflecting the reality of his creative life, that what he imagined had first to be observed. Truman Capote and Tom Wolfe would later make the effort fashionable; Joan Didion would make it personal. “You might call it emotionalized reportage,” Algren wrote, “but the data has to be there.”

By the time he finished A Walk on the Wild Side, he had been on the move for almost two years and had stayed in over a dozen different buildings. “I think the farther away you get from the literary traffic,” he said, “the closer you are to sources. I mean, a writer doesn’t really live, he observes.” His editor at Doubleday turned the book down. Asher sees its faults, feeling that its tone is bitter, cynical, and incoherent, with a naive central character who has “no personality to speak of.” One of the strengths of Asher’s vivid, vastly insightful book is its joy at the achievements of its subject, so he has earned a few doubts, and, indeed, A Walk on the Wild Side lacks the literary texture of Algren at his best. It offers much more than the details of a wastrel’s journey, however. In advance of the 1960s, it provides a picture of a drifter’s resistance to the meritocratic lie surrounding him, and is a jazz-like, spontaneous rejoinder, asking what we wish for when we wish to be entertained. The book’s sing-song lament and day-glo descriptions are sui generis:

There were stage shows and peep shows, geeks and freaks street. It wasn’t panders who owned the shows…. There were creepers and kleptoes and zanies and dipsoes. It was night bright as day, it was day dark as night, but stuffed shirts and do-righties owned those shows.

For a Do-Right Daddy is right fond of money….

When we get more houses than we can live in, more cars than we can ride in, more food than we can eat ourselves, the only one way of getting richer is by cutting off those who don’t have enough. If everybody has more than enough, what good is my more-than-enough? What good is a wide meadow open to everyone? It isn’t until others are fenced out that the open pasture begins to have real value.

In a letter to his friend Max Geismar, Algren wrote, “I made myself a voice for those who are counted out,” and his effort still stands. Asher’s biography makes clear the extent to which Algren became a victim of the paranoia of his times. “He never knew how many of his friends and professional contacts the bureau had spoken to,” Asher writes,

or how closely they were watching him, so when publishers began distancing themselves from him, he assumed his work simply wasn’t wanted or wasn’t good enough. He blamed himself for the resulting anxiety and depression, and when he discovered he couldn’t concentrate well enough to write the way he once had, he attributed his trouble to personal weakness—when, in fact, the truth was far more complicated.

He went mad, he nearly drowned, and, in later life, he became a kind of hack and a clownish shadow of his genius self. “He had been promised one world and then found himself in quite a different one,” Beauvoir said of him, “a world directly opposed to all his convictions and all his hopes.”

Novelists made their way to Algren. He is a premier conscience in American letters and an assurance that style matters. Don DeLillo turned up to see him and found he was without a typewriter, so he loaned him one. Thomas Pynchon, Terry Southern, Russell Banks, and Cormac McCarthy all felt they owed him something. Algren himself liked to quote the baseball player Leo Durocher, who titled his memoirs Nice Guys Finish Last. He had come to feel that his writing wasn’t wanted. “I don’t have the belief,” he said. But reading the best of Algren is an experience in having one’s beliefs replenished. He may have lost himself in the effort to be true, but on the page he’s as fresh and alarming as this morning’s news. In his last years, people would often see him walking in the old neighborhoods of Chicago, before he moved to Sag Harbor, stopping to sit on the pavement and watch the world go by. He said he felt the world was watching him go by, but that fear was generously misplaced, for Nelson Algren is a permanence, and his ideal of compassion may be a force of resistance in all we survey.

This Issue

November 7, 2019

The First and Last of Her Kind

A Heritage of Evil