Khaled Khalifa is Syria’s biographer, much as Gore Vidal declared himself America’s. While Vidal gave fictional life to Aaron Burr, Abraham Lincoln, William Randolph Hearst, and other American deities, Khalifa avoids real names: no Assad, father or son, only “the President”; no Baath, only “the Party”; Alawis are “the other sect,” Sunnis “our sect.” Yet their presence dominates the lives of his imagined characters, as in the real Syria.

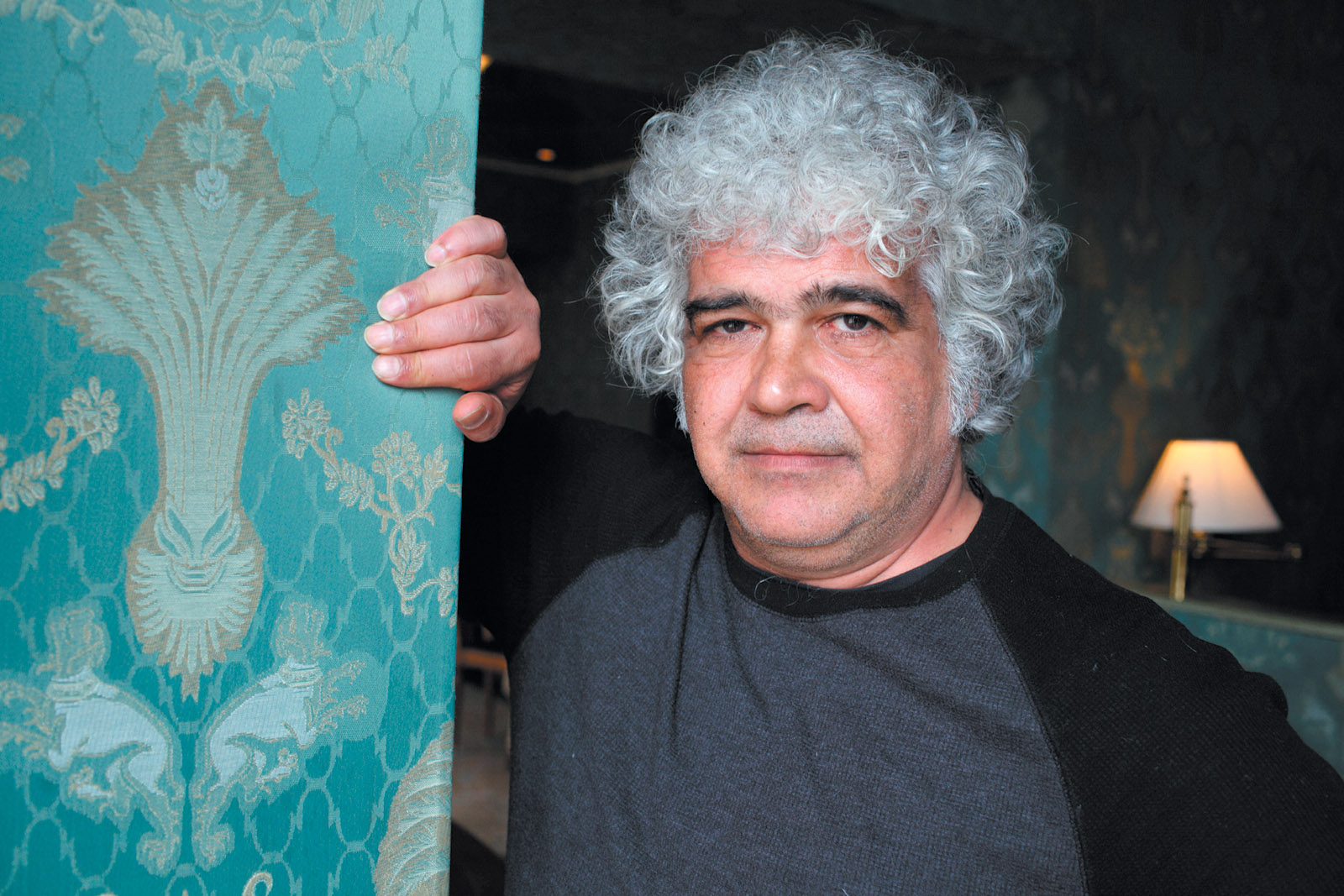

Known in the Arab world primarily as the author of scripts for television and film, the fifty-five-year-old Khalifa has published five novels in Arabic, three of which have been sensitively translated by Leri Price. The first to appear in English was In Praise of Hatred, a complicated García Márquez–like chronicle of an unnamed, decaying family with aristocratic pretensions enduring the clandestine war between security forces and Islamist militants that erupted in Aleppo in the late 1970s. With its labyrinthine souks, decrepit stone palaces, medieval monuments, and heterogeneous populace, Aleppo serves as an apt setting for In Praise of Hatred’s unraveling mystery.

The pride of the old city, largely demolished during the warfare of 2016, is the ancient stone bazaar that Arab and European travelers over centuries praised for its beauty and variety. Philip Mansel, one of many foreign writers to succumb to Aleppo’s Levantine allure, wrote of the souks in Aleppo: The Rise and Fall of Syria’s Great Merchant City (2016), “They stretched for twelve kilometres; through the souks of the rope-makers, the saddlers, the tanners or the spice-merchants, it was said that a blind man could make his way by following the smell of the merchandise.” Khalifa’s Blind Radwan does just that, navigating Aleppo’s physical and political pathways during a turbulent era. A parfumier and necromancer, the Tiresias-like Radwan is “tall and gaunt, clean-clothed, and his hands always smelled of the perfumes he traded in.” As the only male dwelling in the family house who is not a blood relative, Radwan is a sometime servant, occasional confidant, and part-time surrogate father. Among his tasks is guiding the women—three grown sisters and their niece—through the vaulted warren of souks to a weekly rendezvous in the Red Door hammam, the Turkish bath where they strip off the black hijabs that conceal their forms and faces, if not their scents, from the crowds of men they pass and occasionally lust after along the way.

Fragrance permeates Aleppo, the scent of apricot, almond, pistachio, cherry, and olive from the surrounding countryside occupying the city in parallel with peasants loyal to the Party who are colonizing the suburbs. Smell takes precedence among the senses from the opening sentence of the book, when madeleine-like it conjures memories and prompts a search for a lost past: “The smell of the ancient cupboard made me a woman obsessed with bolting doors and exploring drawers, looking for the old photographs I had carefully placed there myself one day.” The unnamed narrator-niece is a latter-day Scheherazade for whom Aleppo’s aromas are as much curse as consolation: perfumes and spices, but also feces, decomposition, and death. In Khalifa’s novels, the living dwell among corpses in ways reminiscent of Nathan Englander’s Poznan family in The Ministry of Special Cases (2007) during Argentina’s “dirty war,” which had much in common with Syria’s at roughly the same time.

Bodies, living and dead, play a central part in this sensual story. For the women of the family, flesh breeds as much shame as pride. When Aunt Maryam tells her niece that “the body was filthy and rebellious,” the pubescent girl reflects, “I obdurately hated my incipient breasts, their two brown nipples beginning to blossom.” Maryam meanwhile “lay in bed like a cold corpse waiting for salvation and the fever of a man.” The fever does not come for her, but marriage, which had already claimed her niece’s mother (who is mostly absent from the story), finds her younger sisters. Safaa weds a Yemeni named Abdullah, whose conversion from doctrinaire Marxism to fundamentalist Islam takes him to the holy war against his former comrades in Afghanistan.

The youngest sister, Marwa, suffers imprisonment in her grandfather’s house until Nadhir, a government death squad officer from “the other sect,” elopes with her. When jihadis attempt to assassinate “the President,” the President’s brother sends this death squad to murder hundreds of prisoners at the notorious Tadmor prison in the eastern Syrian desert—a historical event that Khalifa recounts in frightening detail. Nadhir renounces his fealty to the President rather than participate. One of the victims is Hossam, the brother of the narrator, who belonged to an Islamist assassination cell headed by their Uncle Bakr. The family, standing for Aleppo and the rest of Syria, is disintegrating.

Advertisement

Khalifa moves the saga forward with leaps back in time, pursuing tangents as tightly woven as the strands of a shroud. No peripheral character appears by chance. An artist whom the narrator’s grandfather had met while buying Persian carpets in Samarkand comes to Aleppo to paint the grandfather’s house. “The Samarkandi” moves to Paris, marries, and has a child, but he is not forgotten. His son arrives in Aleppo years later, and Aunt Maryam, a spinster who inherits her mother’s role as disciplinarian of her sisters and niece, becomes obsessed with the boy. Her passion, as with others in the story, goes unstated and unrequited. A chance encounter on another of the grandfather’s carpet-buying pilgrimages, between his servant and the promiscuous wife of their host at a wayside inn, has consequences for the whole family and the war in Aleppo. The daughter of that illicit union, Zahra, reappears to marry Uncle Bakr.

The narrator-niece matures into a woman through a succession of loyalties, first to the underground rebellion that murders neighbors loyal to the state, and later to the state when she denounces her former co-conspirators. When she reverts to jihadism as penitence for her betrayals, the authorities detain her. For years, she suffers the torture and rape that are the fate of most political prisoners throughout the Middle East. Disfigured physically and emotionally by her confinement, she eventually returns to her family. She remembers her last day in prison, when the sadistic warden issued her release papers and “reached out to shake my hand, so I reached out to transfer the poison of my hatred. I shook the hand of my enemy and looked into his eyes, and I knew that he was dead.”

The English edition of the book ends there. The Arabic and French versions include a final chapter. The niece studies medicine under a professor who smells of death and gropes her in his office. “He ground my breasts,” she says, “but I didn’t cry out, I was as cold as ice. Powerless to excite me, he hit me and told me to get out. I took pleasure in being hit by a frustrated man.” She then moves to London, where she practices medicine at a distance from the hatred and aromas that gave her life meaning in Aleppo. Hers is the safer, albeit hollow, fate of the exile, who reflects, “Night fell, a certain lethargy overtakes my body, I am alone and I forever seek faces and metaphors that change places with one another, such a hideous and virginal toad.” Khalifa told me that the last section’s excision by his English publishers infuriated him. The translator, Leri Price, addressed the issue on the ArabLit website: “The final cut was a very bold one, and certainly it meant that the published translation was very different from the original, although I still think that the underlying message was the same.” She did not, however, explain the rationale, and my inquiries to Transworld, publisher of the Black Swan imprint, whose editors removed the chapter, went unanswered.

The second novel by Khalifa to be translated into English, No Knives in the Kitchens of This City, returns to Aleppo and another eccentric family. It is again a first-person narrative, related by the older son of a family of four children whose aged mother prolongs her life beyond her children’s tolerance while dreaming of her many lovers. This family also flaunts past, if spurious, grandeur. Aleppo’s fragrances again powerfully evoke a neighborhood whose identity is being transformed by interlopers from the rural outlands, but sound has a new prominence in this novel. The younger son, Rashid, is a violinist who learns to play under the tutelage of his gay Uncle Nizar. Performing jazz, classical, and Arabic music in cafés and nightclubs releases the two musicians for a time from the oppression, personal as much as political, of life in a repressive and socially conservative country.

The nameless narrator-son writes unsentimentally of his father’s abandonment of his mother for an older American woman, the mother’s construction of a fraudulent genealogy to preserve the family’s status amid penury, and the ways his mother and her brother Nizar “brooded over a history which, for all its beauty, had granted them nothing but misery.” They hide the shame of having a mentally handicapped daughter, “sweet-natured Suad,” whose existence the mother denies to the point of avoiding the child’s funeral and burial.

Uncle Nizar’s love of wearing his sister’s clothes is a family secret that is, in fact, public knowledge and makes his brother Abdel-Monem hate him: he calls Nizar “a faggot who would pollute the family’s honor, and tried to incite [the narrator’s] grandfather either to kill him or throw him out.” Nizar’s homosexuality makes him a target for extremists and government informers alike. His gentleness and capacity for love do not spare him arrest and brutal rape by a fellow prisoner. On his release, he moves with his Christian lover, Michel, to more permissive Beirut, “cursing Aleppo, which he called a fortress of regret.”

Advertisement

Another source of shame is the narrator’s sister Sawsan’s affair with a Party apparatchik named Munzir, who takes her to Dubai as a disposable mistress and servant. When he refuses to marry her, she drunkenly accepts money to sleep with a tourist in a Dubai hotel. The authorities deport her for prostitution—a stain on her and her family’s reputation. Back in Aleppo, she seeks absolution through strict observance of Islam. Her brother observes:

She immersed herself in radicalism and fatwas day after day. She covered her face and began to avoid looking at the handsome men she used to adore watching and imagining in bed with her. She repented her daydreams, her fantasies, and her relationship with Munzir.

The closeted life proves too stifling and insufficiently redemptive: “Sawsan was dissatisfied with her hijab and heavy clothing…. She was trying to rid herself of the smells that still clung to her soul and her body: the odor of the Party, the paratroopers, and the past.”

By her thirtieth birthday, Sawsan is a government informer: “She wanted to erase her old image from her memory. Her reports weighted with slander had destroyed dozens in the interrogation rooms and wrecked the futures of many of her classmates.” Yet she loses faith in what she is doing, realizing “that the demands to ‘reform Party thought’ were no more than words, just like the ‘liberation of Palestine.’”

She seeks refuge with Jean Abdel-Mesih, her former French teacher, whose attentions she had rejected years earlier. He has been dismissed from his teaching post for refusing to sing Party songs and spends his time translating Balzac and caring for his elderly, doddering mother. The Christian Abdel-Mesih, whose family name translates as “servant of the messiah,” offers her sympathy but little else. His is a solitary life suited to liaisons with prostitutes, a function of living in a city whose inhabitants, Khalifa writes,

shared the air of that city but were afraid of each other; Christians afraid of Muslims, minority sects afraid of majorities, and the many afraid of the despotism of the few; races and religions and sects afraid of the President and his mukhabarat [security services]; the President afraid of his aides and his own guard.

When the President—Hafez al-Assad—dies, the narrator’s mother refuses to believe it. “The blood of his victims,” she says, “won’t allow the tyrant to just die.” Her violinist son Rashid can no longer bear the oppression. The narrator writes that Rashid “told me he wouldn’t wait until the grandson of the late President was ruling over us.” Rashid abandons his violin for a rifle and travels to Iraq on the eve of the American invasion of 2003 “to do his duty and defend the lands of Islam against the new crusaders.” After resisting American forces in futile combat at the Baghdad airport, where most of his Islamist comrades are killed, he shaves his beard, sells his rifle, and tries to escape back to Syria. The Americans arrest him as a “foreign fighter,” beat him, and imprison him for more than a year. His family believes he is dead. He convinces his interrogators through a Kurdish interpreter that he is a Christian. His musical expertise provides added evidence that he is not a jihadi, and he is released. On his arrival in Aleppo, he accuses the sheikh who sent him and his colleagues to Baghdad of betrayal. Yet the return does not end his torment:

Rashid deeply regretted returning from Baghdad. There, he had had the opportunity to be brave, to fight and kill in the name of an ideal he didn’t believe in but which gave him a sense of belonging in a group that felt no fear.

Sawsan on her fortieth birthday again seeks solace from Abdel-Mesih, who takes her to dinner at the well-known Wanis restaurant in central Aleppo. For the first time, they hold hands under the table like adolescents. Afterward, also for the first time, they go to bed. Sawsan’s company does not penetrate Abdel-Mesih’s isolation, and despite the earlier years of longing, he loses interest in her. She leaves, returning two months later to tell him she is pregnant. He does not want a child, indeed does not want anyone complicating his life. She refuses to let “her child slip into the sewer of some secret clinic.”

Sawsan seeks out her Uncle Nizar, who has returned from Beirut to Aleppo. His home city, he wrote to his former lover Michel in Paris, “had changed. Farmers no longer followed gay men around and threw stones at them; anyone could get lost in the crowds.” Michel visits Aleppo and, at Nizar’s urging, contracts a mariage blanc with Sawsan to legitimize her child. They move to Paris “as husband and wife to record the birth of Sawsan’s child.” Left behind with his fears and regrets, her brother Rashid hangs himself—his death, in the eyes of Uncle Nizar, who predicted it, “as simple and clear as pouring out a cup of water onto the parched earth.”

If In Praise of Hatred is Khalifa’s Trojan Women, Death Is Hard Work is his Odyssey. It begins with a young man named Nabil, whose pet name, Bolbol, means nightingale, in Damascus at the bedside of his dying father, Abdel Latif. He enjoins Bolbol to bury him in his native village of Anabiya, from which he had escaped years before: “After all this time, he said, his bones would rest in his hometown beside his sister Layla; he almost added, Beside her scent, but he wasn’t sure that the dead would smell the same after four decades.”

Like the paternal ghost’s command to Hamlet to “revenge his foul and most unnatural murder,” Abdel Latif’s wish plunges Bolbol into irresolute action that challenges his endurance. Along with his brother, Hussein, and his sister, Fatima, Bolbol undertakes a journey north with the shrouded and iced corpse in the rear of Hussein’s minibus. The drive to Anabiya should take about six hours in peacetime, but Abdel Latif dies at the height of the civil war that engulfed the country in 2011. Army checkpoints, jihadi marauders, blocked roads, and sporadic combat impede the siblings’ progress as Polyphemus, Scylla, and Calypso did Odysseus’s. Six hours become an interminable three days and nights fraught with danger, testing the ability of the siblings, who have not spent more than an hour together over the previous ten years, to bear one another at all.

Almost immediately, the catch-22 absurdity of wartime Syria presents itself when security forces at a checkpoint arrest Abdel Latif’s corpse, because it turns out that he had worked with rebels in a besieged village for two years. He is a wanted man, dead or alive. An officer demands certificates to prove that the old man is dead and no longer under suspicion, the rotting corpse being insufficient evidence for officialdom. Each checkpoint throws up similar inanity, usually resolved with bribes. The further Hussein drives from Damascus, the more reasonable, even sympathetic, the soldiers on roadside duty become. Yet with every hour in the heat, the body is deteriorating and smelling more rancid.

In a village that Khalifa calls only “Z,” Bolbol finds his Circe in the person of his lost love, Lamia. The Christian Lamia did not marry him years earlier to avoid angering “her kindhearted, simple country family.” (This is not unlike Khalifa’s own experience: I saw him in Damascus some years ago with a beautiful and sensitive Christian woman whom he loved but whose family resisted her union with a Muslim.) Lamia and her husband, Zuhayr, have turned their modest house into a refuge for six families, including thirty children, displaced by the war. They take in the siblings and put Abdel Latif’s corpse in a local morgue until the family is ready to leave with new documents to explain it. Lamia admires Bolbol’s father as “a great man, a martyr, and a revolutionary,” and she

rewrapped Abdel Latif’s shroud, removing the smelly blankets that were still soaked from the slabs of ice and replacing them with clean ones. She also placed sweet basil around the corpse’s head, perfumed him all over, and gave Fatima the large bottle of cologne to sprinkle on him from time to time.

It emerges that while Abdel Latif was heroic in his defense of the village of “S” where he had been a teacher and tended the martyrs’ graves, he had left Anabiya years before “after he had failed to support his sister Layla in her refusal to marry a man she didn’t love. Not even when she said, ‘I’ll set myself on fire before I marry a man who stinks of rotten onions.’” She carried out her threat on her wedding day, dousing herself in kerosene and setting herself alight. Bolbol, reflecting on his father’s shame, thinks, “Why, after you left it all behind—those cruel faces that knew no mercy—why would you want to be buried on their cursed land?” At every setback, Bolbol, Hussein, and Fatima question and regret their quest.

Leaving the government-held areas for back roads, the trio encounter Islamist militants, many of them foreign, who question and abuse them as severely as the government’s agents had. They too demand bribes. Extremists at a checkpoint north of Aleppo arrest Bolbol to reeducate him in Islamic fundamentals but allow Hussein and Fatima to proceed. The brother and sister reach Anabiya at midnight to find the village nearly abandoned. Their father’s eighty-year-old brother Nayif receives them without affection and tells his son, a bearded jihadi named Qasim, to bury Abdel Latif without ceremony.

Bolbol meanwhile is confined to a cell with twenty other inmates, forced to pray and to justify himself to a sharia court. Fearing execution, he is rescued by Uncle Nayif, who bribes the judge and takes his nephew to Anabiya, where he finds his father buried in a remote corner of the cemetery far from his betrayed sister Layla. What was that three-day ordeal for?

C.P. Cavafy’s advice to Odysseus in his poem “Ithaka” applies equally to Bolbol, whose arrival at Anabiya is more of an anticlimax than the Greek king’s return to his island home. It is not the destination but the journey that gives meaning:

Better if it lasts for years,

so you’re old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

Anabiya does not enrich Bolbol. His expedition, however, gives his life purpose and challenges his fears for a brief moment in the midst of a war he neither condones nor understands. His sole consolation is that Lamia did not believe, as he did, that he was a coward. Returning at last to his hovel in Damascus, he “felt like a large rat returning to its cold burrow: a superfluous being, easily discarded.”

In 1987 I interviewed the Syrian novelist Hani al-Raheb in Damascus. His books were more historical than Khalifa’s, treating World War I’s famine and chaos, in which his infant brother had died, and moving on to the rise of the military wing of the Baath Party in the mid-twentieth century. His novel The Epidemic (1981) dealt with the new ruling class, represented by a brigadier general who is in conflict with his worker brother. “In Arab society, this is important, because family bonds are sacred,” Raheb said. “The struggle goes on until the worker brother is killed at the hands of the secret police, who work for his brother the brigadier.” He had just published The Hills: “It’s about how near we in the twentieth century are to savagery.”

The Syrian Writers’ Union had expelled Raheb two years earlier, and he had lost his teaching post at the University of Damascus, but it surprised me that the censor had nonetheless approved his books’ publication. Raheb said book sales in Syria were so small—three thousand copies made a best seller—that the government could afford to be lax. He added:

The regime is confident that inside each one of us, there is that necessary policeman who works for the government and censors himself without government interference. We have been terrorized into growing this policeman within ourselves.

It turned out, when I met Khalifa years later, that Raheb had been one of his inspirations. “He was the best novelist of his generation,” Khalifa said. “The Thousand and Two Nights is a very important book.” His enthusiasm for the older novelist was such that he recorded nine hours of interviews with him that he used as the basis for a sixty-page profile, which appeared shortly before Raheb died, impoverished, in 2000—the same year as the death of Hafez al-Assad. Yet Khalifa has gone further than Raheb and his contemporaries dared: his books include explicit accounts of torture and murder committed by the government, admittedly balanced with descriptions of similar outrages by its enemies. Such occurrences are no secret in Syria, but they are rarely mentioned.

Khalifa took part in early demonstrations against the Assad regime, and security forces broke his arm in a scuffle. He laughed off the injury, but he has faced regular government interrogation and surveillance. Winning the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in 2013, being nominated for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction a year later, and stints at Iowa’s International Writing Program and Harvard have given him some, but not total, protection.

Khalifa’s fiction moves the Syrian novel beyond the postcolonial didacticism that afflicted previous generations of the country’s serious writers. Ideology is mercifully absent in it. Instead, his tales revolve around stronger motivating forces in Syrian life: hatred; love that excludes no expression of longing, whether heterosexual, homosexual, or asexual; and, most of all, fear. Rather than calibrate rights and wrongs or pit heroes against villains, Khalifa portrays with equal sympathy and equal blame those yearning for freedom, those clinging to security in the embrace of the state, and the rest seeking certainty in religious orthodoxy. He has said of his fellow Syrians, “I write for them, but I do not appease them.”

Khalifa is a hakawati, the storyteller on cold nights in the era before electricity and television who mesmerized fellow villagers with fabulous tales in which they were the principal, if barely disguised, characters. Like any good hakawati, as he surprises and shocks, he makes them laugh—and weep.

This Issue

December 19, 2019

No More Nice Dems

What Were Dinosaurs For?

The Master’s Master