It is 1348. Berna has stolen a book from her father’s library, and now she is getting the gardener to cut her a rose from the grounds of their manor house in Gloucestershire. These crimes, she explains to her cousin Pogge, are nothing compared to the one she had been planning, which was to take her own life by throwing herself into the moat. “Your moat’s not profound enough for drownage,” her cousin points out drily. And anyway, she has a new plan, to which the book and the rose are accessories. Her father is forcing Berna, who is fifteen, to marry a man of fifty. In exchange, Berna’s father will be gifted the groom’s daughter as his new young wife. But Berna won’t be sold. She has read the allegorical poem Le Roman de la Rose, or part of it, and she recognizes true love in the form of the real-life Laurence Haket, a young squire in the king’s army who, like the Lover in her stolen book, has been pierced by Love’s five golden arrows. More prosaically, Haket has distinguished himself at the Battle of Crécy, two years earlier, and been granted land in Calais as a reward. Berna is determined to elope with him to France. She has not yet communicated this information to Laurence Haket.

Meanwhile, in another part of the garden, eighteen-year-old Will Quate (who cut the rose for Berna) is bargaining for his freedom with Berna’s father, the lord of the manor. Will’s father, who was killed at Crécy, was a free man, but his mother is bound. Will doesn’t know his own status—bound or free—and as Berna points out to her cousin, this uncertainty is a deliberate strategy: “My father prefers him to be unsure. He tells him he’s at liberty, then offers him villain land to farm.” Now the manor is required to provide an archer to defend the garrison at Calais, and Will agrees to go in exchange for his deed of freedom, to the disappointment of his fiancée, Ness, a farmer’s daughter, who wants to get married right away. Will is a catch—good-looking and sweet-natured—but strangely behind-hand when it comes to courting. This reluctance may or may not have something to do with his friendship with Hab, the pigboy. In an attempt to egg him on through jealousy, Ness herself has been dallying, with unfortunate consequences. She has recently returned from a visit to an apothecary in Bristol, where she has managed to get rid of the baby she was carrying by Squire Haket. No one has yet communicated this information to Berna.

So the journey from Gloucestershire to Calais begins as true love, individual will, and uncertainty take to the road in James Meek’s freewheeling, exhilarating novel To Calais, in Ordinary Time. “You ne understand allegory,” says Berna to Pogge, in one of several winks to the reader early on, letting us know what kind of journey we are in for. There is an infectious energy to the whole complicated set-up. For a start, we encounter this fourteenth-century drama through a trio of bespoke languages, designed to capture differences of social status. Berna’s tale is told in a slightly elevated English studded with French coinages that have not yet settled into modern usage (so Pogge’s “profound” means physically, not metaphorically, deep). The narrator who relates Will’s story appears to be one of his fellow villagers, who speaks a language almost untouched by French or Latin. Here he describes the villagers preparing Will for the journey: “We cleaned his shoon, that he’d bett with thick leather under-halves for a far fare, and we thrang into church.” Here is the reaction of the villagers to traveling friars selling images of the virgin to ward off the plague:

Most folk, out-take Nack, reckoned the qualm was a tale the priests wrought up to wring out our silver. We ne thought us Christ so stern as to slay us by sickness when he took so many in the great hunger thirty winter before. But we wouldn’t that the priest weened we unworthed him, so we bought likenesses.

Meek explains in a note that he researched his various Middle English dialects with the help of the OED. Initially I read the villagers’ narrative voice as largely invented. So, for example, “out-take” is a lovely rendering of what a Gloucestershire serf might say if he didn’t have access to the word “except.” It turns out it is also real Middle English. The negative “ne,” which everyone in the book uses, puzzled me. It seems an obviously French borrowing, so why are the serfs so familiar with it? But it turns out that “ne” was common in Old English, as well as a host of other languages, so use of the word doesn’t tag someone as educated or elite. Who knew? Such are the pleasing rabbit holes that Meek’s thickly textured language led me down.

Advertisement

The third voice is in the first person. It belongs to Thomas Pitkerro, proctor of Avignon—where the pope had his seat through much of the fourteenth century. Thomas has been sent on papal legal business to Malmesbury Abbey in Wiltshire but—though the job is over and there is nothing to keep him in Malmesbury—he is reluctant to head back home. There are practical difficulties with undertaking the journey, as he explains in the account he writes in precise, fussy, Latinate diction: “It is impossible to be a solitary traveller in these times. I must find company for the journey, yet the roads to the southern ports, previously dense with viators, lie vacant.” But the greater problem is his fear of what he will find when he arrives. He last heard from his household four months earlier, when his servant wrote to explain that “the pestilence” had overtaken the city.

The Black Death was brought into Europe by ship from Central Asia in late 1347 and traveled quickly northward through Italy, Spain, and France. Thomas doesn’t know, but we can easily Google and find out that the death toll in southern France is estimated to have been as high as 75–80 percent. He fears, and we assume, that his friends are dead. In writing to them, he resurrects them: “In perscribing this commentary I create a substitute for my faith in the continued existence of home.”

Thomas’s narrative, written in snatches to his servants Marc and Judith, is part philosophical treatise (he nods to Aquinas, for example), part confession and self-examining autobiography (Augustine), part a record of the experiences, stories, and crimes of the archers with whom he travels to Calais. He is like Chaucer in his tales, a clerk recounting travelers’ adventures, some of which touch on brutal rape and murder, and here Thomas becomes Dante, stepping into the underworld.

Berna, Laurence Haket, Will Quate, and Hab the pigboy think they are in a different book altogether. Their genres are medieval romance, pageant, battle-epic, adventure, pastoral eclogue, and the kinds of fairy tales in which serfs get to bed queens. As they travel from Gloucestershire to the ship waiting for them at the Dorset port (picking up Thomas and the band of archers on the way), they meet giants, cloven-headed men, Welsh bards, a wise boar, and evil men keeping captive damsels in distress. The sheer brio with which Meek introduces yet another literary convention, stock character, or unlikely scenario into his still-somehow-realistic story is thrilling.

At the center of the book is a beguiling tale of lovers mistaking and finding each other in the forest, complete—thanks to two identical wedding dresses—with Shakespearian cross-dressing. At one point, Berna plays herself being played by Hab the pigboy’s sister, who herself is played by Hab, in a kind of triple or quadruple cross. And at this point readers—particularly those familiar with Meek’s political commentary on Brexit in the London Review of Books, his book about the privatization of public services in Britain (Private Island, 2014), his work as the Guardian’s Moscow correspondent (one source for his prize-winning novel The People’s Act of Love, 2005), or his novel about a journalist in Afghanistan after September 11—may be wondering whether there are two James Meeks. Or they may simply be wondering, Why this project? By quite explicitly flagging Le Roman de la Rose as a “key” to the novel, Meek forces us to ask, If this is an allegory, what is it an allegory of?

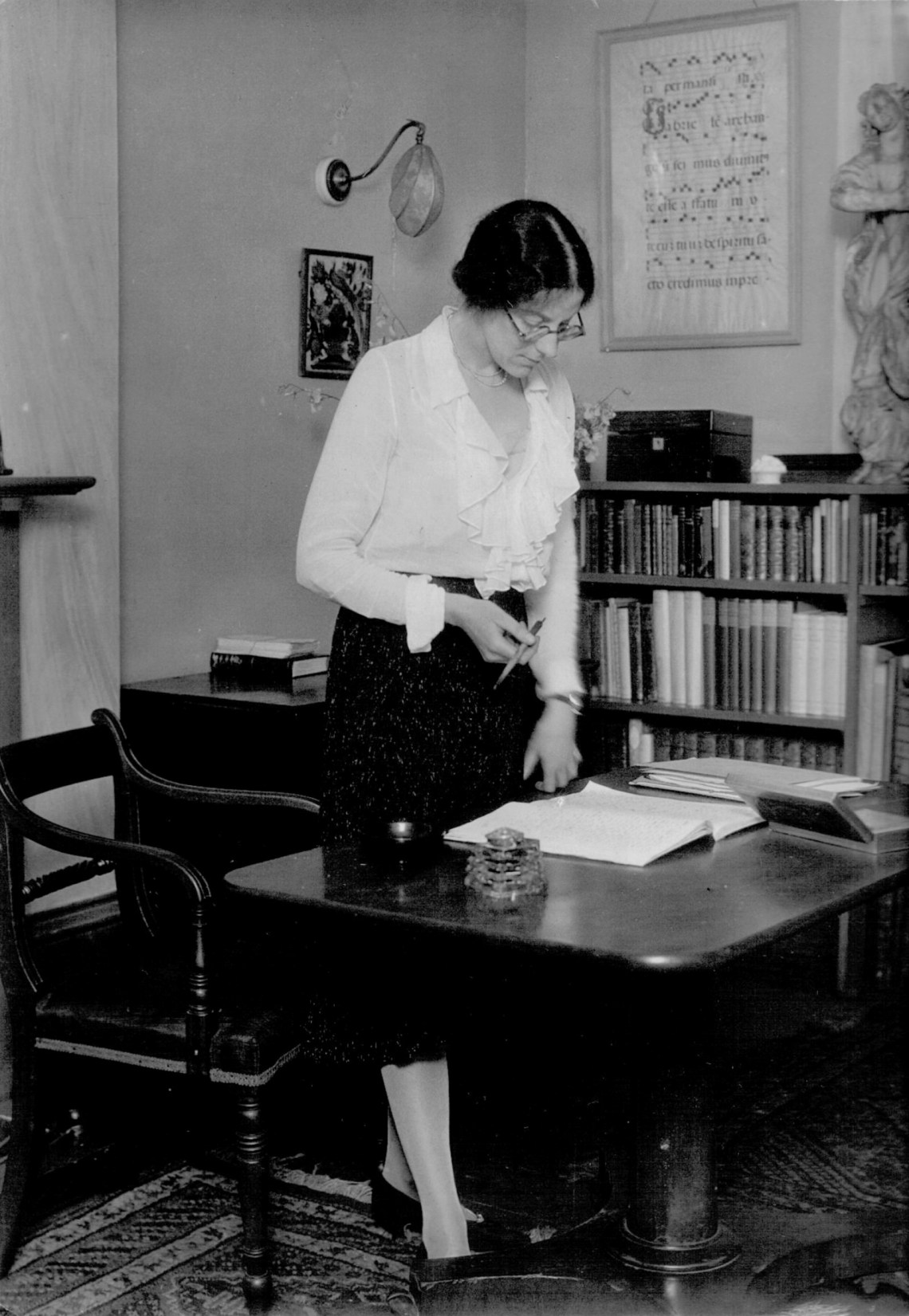

There is a small but highly respectable tradition of English novelists turning to medieval and quasi-medieval worlds in times of crisis. Tolkien’s story of Middle-earth, like the Arthurian romance in T.H. White’s The Once and Future King (based on Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur), was largely written during World War II. Sylvia Townsend Warner’s novel set in a fourteenth-century nunnery in the Fens, The Corner That Held Them, just reissued by New York Review Books, was written between 1941 and 1947, in rural Dorset. Arguably in all three cases the Middle Ages offered respite from the contemporary “pressure of reality” (as Wallace Stevens put it in 1942) while at the same time holding a mirror up to the warring world.

All historical fiction necessarily reflects on the present, but by placing the problem of allegory center-stage (you ne understand allegory?), Meek teases us. He isn’t offering a historical parallel but inviting us to consider how the people of medieval England were encouraged to think about their world, about good, evil, love, desire, and morality, and so to consider the differences—and similarities—between then and now. But he is also asking us to think about how we interpret stories. Allegory is a mode of interpretation as much as it is a genre of literature—so, for example, the Bible can be, and has been, read literally, allegorically, analogically, or morally. One of the things Meek’s novel reminds us is what fun it is to puzzle out hidden meanings, and how important it might be to get your reading right. It’s a bit like the way we take on the role of the detective when we read detective fiction. It is pretty clear what Will stands for—it’s in his name. But we are given work to do in figuring out his fellow travelers. There are plenty of clues that the leader of Meek’s band of archers, for example, stands for more than an individual in a novel, but what exactly? He might be God, or he might be the Devil, and not surprisingly the correct interpretation turns out to matter quite a lot to Will, and therefore to us too.

Advertisement

What these novels by Meek and Townsend Warner share is an ambition to touch and taste the world of the 1300s. They are both works intensely interested in what it means to use fiction to understand human nature in history. “A good convent should have no history,” Townsend Warner writes. “Its life is hid with Christ who is above.” She lays down the challenge for herself, and her reader, early on in The Corner That Held Them. The principal storyline of the novel begins where Meek’s ends, in the late 1340s, as the Black Death courses through southern England; it draws to a close in the early 1380s, in the aftermath of the Peasants’ Revolt. But it takes place inside an inconsequential convent established in a leaky manor house, situated in a marshy, out-of-the-way corner of England—when the villagers there talk about the past, they argue over how far up the local river the Vikings got. “I still incline to call it People growing Old,” wrote Townsend Warner to a friend about her work in progress. “It has no conversations and no pictures, it has no plot, and the characters are innumerable and insignificant.”

Prioresses come and go, novices prove better or worse bets, there are squabbles over dowries and inheritances, laborers’ wages soar in the aftermath of the plague, and the masons leave the new chapel spire unfinished. The account books tally wages along with butter and prunes and tallow and cattle drenches. Outside the walls of the convent, the villagers suffer the impact of the wars in France in taxes and levies, and the nuns are powerless to act for or against anything. For a start, they lack the funds to assuage the anger of the peasants: “Food, clothing, new thatching, the gleaning bell rung an hour earlier, a remission of dues—there is no way of pleasing people that is not costly.” In the end, the main effect of the Peasants’ Revolt on the convent is the loss of its silver altar ware. The nuns bury it to save it from being pillaged, and then can’t remember where they hid it. They end up having to use pewter. Their task is to continue to sing the unchanging chant of the office, as English rural life transforms around them.

About two thirds into the novel, Townsend Warner seems to have lost faith in her plotless, inconsequential story, and felt it necessary to weave in some drama. The thwarted desire of a nun to become an anchorite, or recluse, for example, or a pious nun taking murderous revenge on a fornicating priest and his lover—it’s not that these events are too remarkable to have taken place in the convent, but that they linger too long in the narrative and bear too much significance in the minds of the nuns themselves. Years later, they are still of consequence. It is as though Townsend Warner wanted the convent to have its own history after all, to weigh in the balance against the Hundred Years’ War and the Peasants’ Revolt. But the novel is most successful when it resists significance. Its real subject is indeed people growing old, and facing the fact of their own ordinariness:

And here am I, she thought, fixed in the religious life like a candle on a spike. I consume, I burn away, always lighting the same corner, always beleaguered by the same shadows; and in the end I shall burn out and another candle will be fixed in my stead.

Years later, another cloistered woman experiences much the same feelings of insignificance: “Even her melancholy had forsaken her. She was a quite ordinary nun, who would lead an ordinary nun’s life, no better than the others and no worse, and dying would suffer the ordinary pains of purgatory, no sharper and no lighter.” Townsend Warner’s tone is often arch, and she has a sharp eye for the capacity of the women in this community to bicker and delude themselves. But there is no mistaking her empathy for them as they struggle with their own mortality. Human nature doesn’t change much, she implies, and she clearly has no time at all for the idea that modern subjectivity came into being with the Renaissance. She creates an interior voice that speaks across the centuries.

“Ordinary time” is that part of the liturgical calendar, between Easter and Advent, when nothing much happens. But ordinariness also stands for life lived under temporal constraints, for the commonplace experience of being human. Questions of free will and the shape given to private thoughts and desires hover at the margins of both of these novels. And it cannot be a coincidence that in both novels those questions are posed by a clerk who takes on the role of a priest, without having the authority to administer the sacraments or to shrive sins. In The Corner That Held Them, the false priest is Ralph Kello, a clerk who turns up at the convent gate in 1349, claiming to be a priest because he is hungry, and who becomes trapped by his lie for thirty years. In To Calais, it is Thomas, a religious scholar but not an ordained priest, who is forced by circumstance to hear the last confessions of dying victims of the plague. In the act of confessing to the living, rather than to God, whose pardon is required? In the absence of the sacrament, the confessions are nothing but stories—nothing more or less than a means for people to ask forgiveness of one another, and to give it. In this scenario confessing is like talking, or thinking, and the basis of enlightenment measured on a human, and ordinary, scale.

Some reviewers have suggested that Meek’s novel offers parallels with life today under Brexit. To back this claim up they have not only Meek’s book Dreams of Leaving and Remaining, published earlier this year, which anatomized the “dream visions” powering opposing views of Europe in Britain, but also the fact that Edward III’s wars with France were a struggle for control of European cultural capital, with Calais the gateway to power. Then there is the role of language in class difference and the ways language affects notions of “country” or “nationhood.” The novel prompts its readers to think about community and defense and violence, not least the idea of “pestilence” coming from across the Channel. Some have argued that the book is about environmental catastrophe, and they can point to Meek’s own comment that he began writing it in 2013 as a novel about climate change—the Black Death an allegory for near-total human destruction. Both these readings seem to me to be true-ish but not true enough. The trouble with them is that they assume the various love stories woven through the novel are vehicles for weightier subjects. But at its heart this is a book about the transformative power of love.

Meek has a lot of fun with “romance” in the novel. There are moments, as Berna and Laurence spar with each other, when we could be reading Jane Austen or Muriel Spark. Berna’s stolen book, Le Roman de la Rose, provides the template for a series of dressing-up and gender-bending plot twists—and I am being careful here not to reveal too much—but it also lays the ground for a debate on the true nature of love: “the very mystery is that there is only one Love. Where does he have his habitation?” Is true intimacy grounded in friendship or in sex, and is it possible to have both?

It is in these debates that Meek’s contemporary commentary becomes clearest. He offers us a fourteenth-century typology of love and fear, and asks us to confront it, and the parts of it that we still live by, with a more challenging typology of love’s forms and possibilities for the present moment. He is writing about characters who leave home to make new lives—migrants, in fact. These travelers are English migrants crossing the border into new worlds on the continent. As Thomas reflects, there are men who travel in order to come home again (the man whose “concept of liberty demands his ability to enjoy it on his native terrain”). And there are those who travel in order to change themselves. The word “imagination,” with its French root, is not known to the archers or to the Gloucestershire villagers Will and Hab. Berna explains that “it is the sleight of mind that gives the speed to know things not as they are, but as they might be, were God or man to work them otherwise.” The novel has its share of haters as well as lovers, but Meek is unequivocally on the side of those who embrace dreams, desire, and hope in all their uncertainty, simply for the chance that things might be otherwise.

This is a novel in praise of the courage of the young, whose hunger for freedom and connection may be all that will save Europe, if not the world. It does not seem fanciful to imagine the young people currently sailing the earth to summits on the environmental crisis as characters in Meek’s book. But the voice that stayed with me belongs to Thomas—middle-aged, regretful, and piercingly honest about his own past failures of imagination. His account of his journey, punctuated by his series of confessions to his servants, becomes a love letter written too late—in effect a letter written only to himself, in which he unravels the nature of the self-deceptions that have kept him imprisoned, fearful of his own desire. He has behaved well, and generously. He has understood himself and others. But he has not lived, because he has not truly loved, and he knows it.

And on the other side of love: “unmitigable loneliness.” Sometime in the 1350s, Dame Alicia, one of Townsend Warner’s beleaguered Norfolk prioresses, makes a bid for friendship with the nuns in the community. She is worried about the convent’s finances, and she decides to take the sisters into her confidence. They offer no response at all, and she is overwhelmed by a feeling of isolation:

There can hardly be intimacy in the cloister: before intimacy can be engendered there must be freedom, the option to approach or to move away. She stared at their faces, so familiar and undecipherable. They are like a tray of buns, she thought.

The last sentence is typical of Townsend Warner—with a sudden telescoping of perspective, we are inside Dame Alicia’s weary worldview, shaped by years of keeping going in the same domestic, constricted sphere. All the women have come out of the same oven: “One hand pulled them apart from the same lump of dough.” Thomas Pitkerro also knows there is no intimacy without freedom, and no transformation without love. But Meek’s strange novel about a young man named Will suggests that for those with the courage to take it, freedom is possible and may change the world.

This Issue

January 16, 2020

The Designated Mourner

Is Trump Above the Law?

It Had to Be Her