In October 1922 Conservative members of Parliament voted to fight the next election as a separate party, calling time on their coalition with the Liberals, with whom they had governed Britain since 1915. David Lloyd George resigned immediately as prime minister, never to hold office again. Over the next twenty-four months, there were three general elections, four governments, and four prime ministers. So the recent turbulence of British politics, with its three elections and three prime ministers since May 2015, wasn’t unprecedented. In October 1924 the Conservatives under Stanley Baldwin swept away the first-ever Labour government in a landslide, and in December 2019 the Conservatives under Boris Johnson likewise routed the Labour Party. Baldwin was educated at Harrow and Cambridge and was at one time president of the Classical Association; Johnson went to Eton and Oxford and likes to parade the classics.

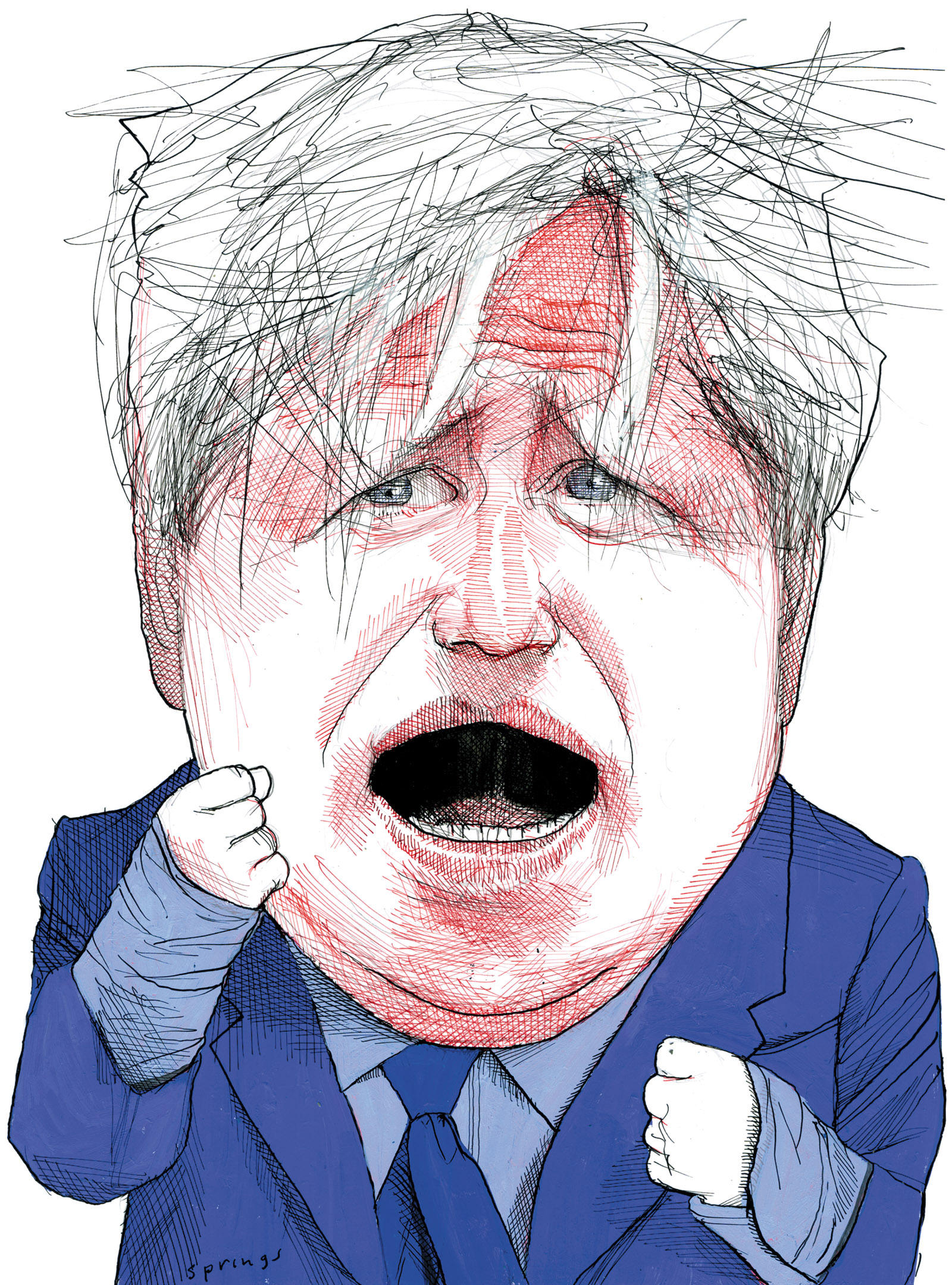

And there the comparisons end. Baldwin had damned Lloyd George—“A dynamic force is a very terrible thing; it may crush you, but it is not necessarily right”—in words that could apply to Johnson, who has been compared to Disraeli and even Churchill but may resemble Lloyd George more than either. “His rule was dynamic and sordid at the same time,” A.J.P. Taylor wrote of “LG”; “he repaid loyalty with disloyalty,” and, not least, he was “the first prime minister…since the Duke of Grafton [in the 1760s] to live openly with his mistress,” until now. “A very terrible thing” describes how his enemies and critics see Johnson, but he has certainly crushed them. By backing Leave in the 2016 referendum on British membership in the European Union, seizing the leadership of the Conservative Party last summer, precipitating an election, and then winning a large majority, he has achieved total command of domestic politics.

In October Johnson called for Britain “to be released from the subjection of a parliament that has outlived its usefulness,” which one commentator called “appallingly fascistic” words, but they worked. The parliamentary stalemate of the past three years is broken. Any forlorn hopes of somehow reversing the result of the referendum are finished, the Brexit legislation has been passed, and on January 31, after forty-seven years “in Europe,” the United Kingdom leaves the European Union.

How did this startling turn of events come about? In 2015 David Cameron and the Tories confounded the pundits by winning a parliamentary majority. As I wrote in these pages at the time, a real portent at that election was the rise of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), the right-wing Europhobic party led by Nigel Farage.1 UKIP has only ever elected one MP to Parliament, but in 2015 it won 12.6 percent of the popular vote, and its candidates ran second in 120 districts, forty-four of them held by Labour. Farage has never himself won a parliamentary seat, but he has some claim to being the most influential British politician of our time. Even so, the Parliament elected in 2015, like those elected in 2010 and in 2017, contained a clear majority of MPs who supported remaining in the EU, including most Tory members.

Before the 2015 election, Cameron had promised to hold a referendum on EU membership, as a tactical maneuver to neutralize UKIP and the noisy Europhobes in his party. In 1975 Harold Wilson had done the same: two years after the United Kingdom had joined the European Economic Community (EEC), he held, and easily won, a referendum to confirm its membership as a way of dealing with divisions in his Labour Party. In 2004 Tony Blair announced out of the blue and to the horror of his Europhile supporters that a referendum would be held on the new European Constitution. This was the result of a private deal he had made with the relentlessly Europhobic Rupert Murdoch, in return for the continuing support of Murdoch’s tabloid The Sun before the general election the following spring. When that election coincided with referendums in which the Dutch and the French rejected the constitution, Blair told the Commons that now “there is no point in having a referendum, because of the uncertainty it would produce,” and was reminded by the Tory MP Angela Browning of what he had told The Sun only weeks before: “Even if the French voted no, we would have a referendum. That is a government promise.”

Quite lacking Wilson’s sinuous guile or Blair’s shamelessness, Cameron set a trap and then walked into it himself. He may have thought that he could avoid keeping his promise like Blair, or that he could pull off a victory like Wilson. Had he, or his advisers, had the wit or knowledge, he could have quoted the two outstanding prime ministers since the war. In 1945 Churchill wanted to hold a referendum to extend his wartime coalition until the Japanese surrender but was told by Clement Attlee, still deputy prime minister in the coalition though soon to rout Churchill and the Tories in a historic election, “I could not consent to the introduction into our national life of a device so alien to all our traditions as the referendum, which has only too often been the instrument of Nazism and fascism.” And thirty years later, Margaret Thatcher agreed: “Lord Attlee was right when he said that the referendum was a device of dictators and demagogues.”

Advertisement

We don’t have fascism or dictators in England yet, but we have plenty of demagogues. The Leave campaign during the referendum was a display of naked and frequently mendacious demagoguery, quite possibly with Russian help, and Thatcher’s apprehensions have been amply justified by events. After losing any vote, it can be tempting to say, in Éamon de Valera’s deathless words, that although the people might seem to have declared their will, “they did not declare that will as we know it to be their will.” But referendums really are dubious, as Attlee and Thatcher said, not least because if you ask people a question about This, they may well give an answer to That.

In every opinion poll for many years past, “Europe” was far down the list of voters’ concerns. Very few cared about the European Court of Justice and the Brexiteers’ other bugbears; in one poll four years ago, barely one British citizen in a hundred thought membership in the European Union was the most important political question. But voting against “Europe” was an expression of the general and perfectly understandable resentment of so many people in postindustrial England who felt ignored and disdained by their leaders. The divisions exposed by the referendum were depressing and ominous. If the vote had been confined to those over sixty, Leave would have gained far more than 52 percent, but if confined to those under thirty, Remain would have won easily; nearly 70 percent of university graduates voted Remain, about the same percentage of those with minimal educational qualifications voted Leave, and that divide was reflected again at the 2019 election. The Oxonian Johnson could borrow the undereducated Donald Trump’s words: “I love the poorly educated.”

That’s not the only transatlantic echo. At the heart of the December election was the disastrous failure of Labour and its leader. Three years before, on the night the “firewall” states Hillary Clinton had neglected because they were so obviously safe—Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin—fell to Donald Trump, one of her team exclaimed, “What happened to our fucking firewall?” Labour supposed that its own “red wall” in the working-class Midlands and North was safe forever, and in the early hours of December 13, as seats held by Labour for more than seventy or eighty years fell to the Tories—Wrexham, Bolsover, Bassetlaw, Wakefield—someone at Labour headquarters likely asked a similar baffled question.

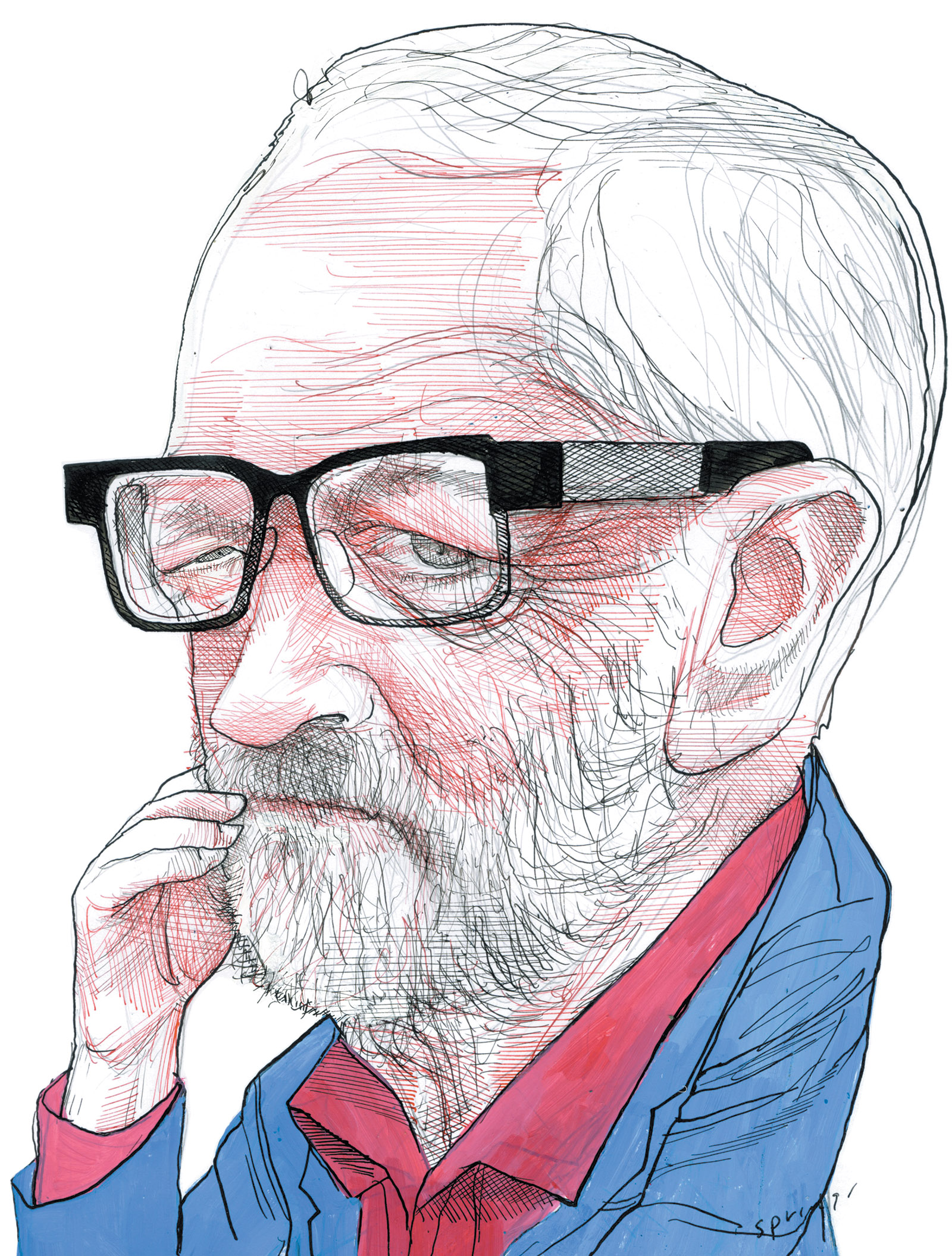

Only an accident of history had made Jeremy Corbyn Labour leader in 2015: Labour was demoralized after two defeats, Blair’s legacy was discredited by needless wars and personal greed, a change to party rules meant that anyone who paid less than the price of a pint of beer could join and vote for the party leader, and there was a sudden craze for a man most voters had never heard of. Corbyn had acquired a package of hard-left views and prejudices more than forty years before, and he has never since changed his mind, or seems to have thought very much, about anything. One of those views was that “Europe” was a capitalist conspiracy. Corbyn voted against EEC membership in 1975, opposed every European treaty since, and damned the single market as “free trade dogma.” His halfhearted, mumbled support for Remain in the referendum was unconvincing, Labour’s position was hard to discern, and many Labour districts voted Leave. Nonetheless, when Theresa May became prime minister after the referendum and Cameron’s departure, and then called an unnecessary election in 2017 in the expectation of increasing her majority, Labour enjoyed an unforeseen resurgence, rising from 30 percent of the vote in 2015 to 40 percent in 2017.

Then the bubble burst, and that vote now looks like what the stock market calls a dead-cat bounce. Although Corbyn has been an MP since 1983, few voters had any idea who he was when he became leader, but the more they learned about him the less they liked him. That package of views—his claim that the Falklands War was “a Tory plot to keep their money-making friends in business,” “anti-Zionism” that looked like anti-Semitism, support for the Irish Republican Army when it was killing the sons of working-class families—caught up with him. Corbyn claims not to be personally anti-Semitic, but the miasma of anti-Semitism in the Labour Party isn’t just a figment of critics’ fevered imaginations, and it did a good deal of damage. Polls had already shown Corbyn’s extremely unfavorable personal ratings, even before most Labour candidates during this election reported the voters’ sheer, acute dislike for him. The Labour vote fell back to 32 percent, and with 202 seats the party now has its smallest number of MPs since 1935.

Advertisement

But it won’t do to arraign Corbyn alone. If anything, more blame for the eclipse of Labour, and for Brexit as well, attaches to Blair, who wrote in The Sun on April 23, 1997, “On the day we remember the legend that St George slayed a dragon to protect England, some will argue that there is another dragon to be slayed: Europe.” That was a week before he won his first landslide election. He claimed to be a good European but was a false friend to Europe—always looking over his shoulder at the right-wing Europhobic press, rarely saying anything positive about Europe—before his participation in the catastrophic invasion of Iraq split Europe apart.

One of Blair’s worst mistakes concerned immigration. When the former Soviet bloc states in Eastern Europe, with their much lower wages, were welcomed into the EU in 2004, the principle of free movement was modified so that Western European countries could restrict for some years immigration from them. Germany and France took advantage of this; distracted by his great Levantine crusade, Blair did not. Soon there were a million Poles in England, and I’ve learned to say “mulţumesc” rather than “thanks” to taxi drivers, since so many of them in Bath, where I live, are Romanian. And immigration really was a concern of Labour voters who chose Leave, and then Johnson.

Quite possibly the Labour Party in its present form is finished—and is not alone in its plight. The right-wing press never ceased howling about the terrible threat from Corbyn, but no effusion was weirder than one from Allister Heath, the editor of the Sunday Telegraph: “Across the West, the forces of the extreme Left are on the march.” As anyone can see, across Europe the far left is everywhere in retreat, and the moderate left as well. Historic leftist parties—the French Socialists, the German Social Democrats, and others besides—reflect Labour’s grave condition. England today desperately needs an effective opposition party, which can’t be provided by Corbyn or any likely successor. And it desperately needs a serious radical party that can create an alliance between working-class and educated liberal voters. Corbynite Labour isn’t it, nor was Blairite New Labour, but something might yet arise from their ashes.

With all that, our latest political drama has one central character, and the name “Boris” screams from headlines in a London press that has surpassed itself in its hysterical adulation. For much of the last century, the Daily Telegraph was a bastion of respectable suburban conservatism. It was gray, even dull, but also conspicuously honest. When Lord Camrose owned the paper, from the 1920s to the 1950s, he made a cardinal principle of objectivity and would write sharp notes to the editor saying that his lead story read like a handout from Conservative Central Office.

Today’s Telegraph isn’t just a Johnson fanzine; it has a ring of the official journal of some third-world statelet or of a vast despotism worshiping the Great Helmsman or Dear Leader. “It’s time critics saw Boris for the Churchillian figure he is,” screeches Tim Stanley as he drools over “the blond magnificence.” “Boris’s win proves the soul of our nation is intact,” shrieks Allison Pearson. “Dear Boris, Hallelujah!” shouts Andrew Roberts, the (by his own account) “extremely right-wing” polemicist and historian. That comparison with Churchill is repetitiously made, along with endless invocations of 1940. Having acclaimed the Churchill biopic Darkest Hour as “splendid Brexit propaganda,” Charles Moore calls Johnson Churchill’s reincarnation, who “sees trouble coming from the European continent and risks his career on the point…unites country, wins.” Besides that, Moore says that Johnson “is one of the very few people I have ever met who can be described as a genius.”

Come to think of it, maybe there are comparisons with Churchill. In 1906, after he had bolted from the Tories to the Liberals and been rewarded with office, the High Tory National Review called Churchill “the transatlantic type of demagogue (‘Them’s my sentiments and if they don’t give satisfaction they can be changed’)…. It will be interesting to see how far a politician whom no one trusts will go in a country where character is supposed to count.” Three years later, Lord Knollys, private secretary to King Edward VII, said that, however Churchill’s conduct might be explained, “Of course it cannot be from conviction or principle. The very idea of his having either is enough to make one laugh.” And when in the early 1930s Churchill attached himself to the reactionary but sincere Tories who were fighting self-government for India, Lord Selborne, one of their number, said, “He discredits us; we are acting from conviction but everybody knows Winston has no convictions; he has only joined us for what he can get out of it.”

Words like “fascistic” don’t really explain “Boris.” If the only “ism” Hollywood understands is plagiarism, then the only “ism” Johnson understands is opportunism. Dominic Lawson is one more of the gaggle of Europhobic “calumnists or columnists” (Churchill’s phrase), but not stupid or unobservant, and he spells out a truth universally acknowledged that still deserves to be italicized: “Johnson was never in favour of Brexit, until he found it necessary to further his ambition to become Conservative leader.” The idea of Johnson having any conviction or principle is enough to make anyone laugh; he only joined Leave for what he could get out of it. But his support for Leave in the referendum was reckoned more important than anyone else’s, maybe even decisive, and so the course of our history has been drastically altered by a man who is at once ruthlessly ambitious and totally unprincipled.

That is not a unique opinion. Moore’s predecessor as editor of the Daily Telegraph was Max Hastings, who dismisses Johnson as a “charlatan and sexual adventurer.” Matthew Parris, a columnist with the Times and a former Tory MP and aide to Margaret Thatcher, defines Johnson’s career as “the casual dishonesty, the cruelty, the betrayal; and, beneath the betrayal, the emptiness of real ambition.” Ferdinand Mount, former editor of the TLS and also once an adviser to Thatcher, for whom he wrote the 1983 Conservative election manifesto, thinks Johnson “a seedy treacherous chancer.” More temperately, and quite correctly, Hastings says that “scarcely anybody who knows him well trusts him.” One of the more repellent sights of the past year was Tory MPs who to my knowledge don’t trust or respect Johnson at all nevertheless jumping on his bandwagon, and one or two newspaper editors as well. This isn’t written out of personal animosity. I’ve known Johnson for years, and when he was editor of The Spectator and I wrote for him, our dealings were perfectly cordial, but then I’ve dealt with plenty of affable rascals in my time.

Wherein can Johnson’s “genius” be found? He was of course a journalist before he was a politician, like Churchill and Mussolini. He thrilled Telegraph readers with his transgressive naughtiness, calling African children “piccaninnies,” gay men “tanktopped bum boys,” Islam “the most viciously sectarian of all religions,” and Hillary Clinton “a sadistic nurse in a mental hospital.” Most breathtaking of all, he denounced single mothers for “producing a generation of ill-raised, ignorant, aggressive and illegitimate children,” which really takes a prize for chutzpah in view of his own personal life. (Asked by an interviewer how many children he has, Johnson refused to answer, and to be fair he may well not know.)

Or is his genius found in his books? Fintan O’Toole has written in these pages about Johnson’s The Churchill Factor, which he wrote five years ago and which became a best seller.2 For Johnson, Churchill sometimes sounds “like a chap who has had a few too many at a golf club bar,” an enemy of his is an “ocean-going creep,” one of his friends is a “carrot-topped Irish fantasist,” Lord Halifax is “the beanpole-shaped appeaser,” one thing or another is “wonky…bonkers…tootling.” This is the Finest Hour as told by Bertie Wooster.

In 1940 Churchill criticized a Foreign Office draft that erred “in trying to be too clever” and was “unsuited to the tragic simplicity and grandeur of the times and the issues at stake.” What might he have said about the “genius” Johnson? But then maybe Johnson really is the man for our own age, an age incapable of tragic simplicity and grandeur. Orwell’s Newspeak was a language constructed so that it was strictly impossible to express any subversive sentiment. In Borispeak it’s equally impossible to say anything serious, and he may indeed never have said, written, or thought a single serious thing in his life.

Although he still leads the Conservative and Unionist Party of Great Britain, that’s now a misnomer. It was once a truly national party, throughout the United Kingdom, which could win a majority of seats in Scotland less than seventy years ago, and the right wing of the party always professed a loyalty to unionist Ulster. But the union has begun to fall apart. Johnson supposedly pulled off a coup by negotiating a new deal with Brussels, in which the EU (afflicted by its own Brexit fatigue) made a few slight concessions, but much the greatest capitulation was Johnson’s: he agreed that Northern Ireland should have a customs and regulatory regime different from Great Britain’s, avoiding a hard border with the Irish Republic while creating a border in the Irish Sea—the very thing the right-wing Tories and May’s Democratic Unionist allies had said would be intolerable.

True to form, Johnson followed treachery with mendacity, denying that he had done what he had done. But in December, for the first time, more nationalist and republican than unionist MPs were returned from Northern Ireland, and the Scottish National Party won forty-eight of fifty-nine seats in Scotland. Almost more startling, a poll last summer of Conservative Party members found that a majority wanted Brexit even if it meant Scotland and Northern Ireland leaving the Union. It is now in no sense a Unionist party—and barely conservative, either.

There was a time when the Tories supported not only the Union but the unity of Europe, and so did their newspapers. Sir Colin Coote, the editor of the Daily Telegraph from 1950 to 1964 and a veteran of the Great War, in which he had been wounded and decorated, was a strong advocate of British membership in the Common Market. One Conservative prime minister, Harold Macmillan, also a former infantryman wounded in the Great War, tried to join, and another, Edward Heath, a veteran of the next war, did so. Even Margaret Thatcher, for all her later battles with Brussels, campaigned to stay in 1975 and ratified the crucial Single European Act, which committed the European Community to establishing a single market.

“Yes, this is a right-wing coup,” Mount said when Johnson formed his cabinet, brutally ejecting his enemies, and that was before he purged dissident Europhile MPs from the party, among them two former chancellors of the exchequer, a former attorney general, and Churchill’s grandson. Every Tory candidate at the election had to swear to support Brexit, and Johnson now has behind him a parliamentary party as servile as the Supreme Soviet. Farage may never have been elected to Parliament, but it turns out he didn’t need to be: his UKIP has metastasized into the “Boris Tories,” an English nationalist party that has less affinity with continental Christian Democratic parties like Angela Merkel’s CDU than with the Rassemblement National (formerly the Front National) in France and Alternative für Deutschland.

Except in one respect: those European parties of the nationalist right are mostly critical of American power. By contrast, and to put it in the terms of the war they are always invoking, the Tories and the Telegraph are résistants toward Brussels, but pétainistes toward Washington. The Brexiteers’ favorite word of contempt has been “vassal” or “vassalage,” to describe Britain’s supposed subservience to the EU, but they never stop talking about the “special relationship,” or nowadays the “Anglosphere,” with Roberts insisting that “Britain will be better off as a junior partner of the United States than an EU vassal.” This is a tricky claim after we have seen what “junior partnership” means in practice: whatever else Brussels may have done, British troops have never been sent to the Middle East at the behest of Jacques Delors or Jean-Claude Juncker to fight in criminal and catastrophic wars. In fact, when Roberts says “junior partner,” he appears to mean “vassal.”

Now Donald Trump presents a grave problem for the Anglospheroids, and for Johnson, who desperately needs Trump’s goodwill for an Anglo-American trade deal but knows that the president’s very name is toxic here. As the luck of the calendar had it, the NATO conference in London took place just before the election, and it was most amusing to see the prime minister desperately avoiding any contact à deux with the president. Then came Trump’s assassination of Qassim Suleimani, and we could tell how important the “special relationship” still is from the fact that Johnson was the very first leader Trump chose not to inform of his decision. The crisis found Johnson sunning himself in the West Indies, and on his return, his government was at sixes and sevens. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called on Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab to repeat the president’s demand that America’s allies should renounce the Iran nuclear deal. Like a good vassal, Raab said that the government was “looking very hard” at the deal, but almost simultaneously Johnson spoke to Hassan Rouhani, the Iranian president, to stress his support for it. Then on January 14, Johnson turned around and said the earlier deal was “flawed,” and so “let’s replace it with the Trump deal.” But really, does “Brexit Britain” have any coherent foreign policy at all?

Amid those vulgar evocations of the war against the Third Reich, two splendid nonagenarian Englishmen who knew that war firsthand died in November: Field Marshal Lord Bramall, a former head of the British army, and Sir Michael Howard, the great historian, Regius Professor of Modern History at Oxford, and professor at Yale. In another life, both had won the Military Cross leading infantry platoons, Bramall with the 60th Rifles in Belgium, Howard with the Coldstream Guards at Salerno. Both were committed Europeans and Remainers, and there’s a bitter contrast between such men and the saber-rattlers of the Europhobic right, whose bellicose sub-Churchillian rhetoric is in inverse ratio to their experience of gunfire.

Not long after the referendum, I had lunch in a Berkshire pub with Michael Howard and Mark James, his civil partner. Michael raised his glass with the words, “To Hell with Brexit,” and he returned to the subject, as well as our new prime minister, when I last saw him, physically frail but completely lucid. Max Hastings was a close and loyal friend of Michael’s and was with him when he died, just after his ninety-seventh birthday. He has recorded one of the last things Michael said, about the “extraordinary bathos” with which his long life was ending. Michael’s earliest memory was of the general strike in 1926; he remembered the rise of Hitler; he was a schoolboy in 1940, a soldier two years later, before his illustrious career. And now his story was ending “under the prime ministership of Boris Johnson”—spoken with awed contempt. What can one add?

—January 16, 2020

-

1

“Britain: The Implosion,” June 25, 2015. ↩

-

2

“The Ham of Fate,” August 15, 2019. ↩