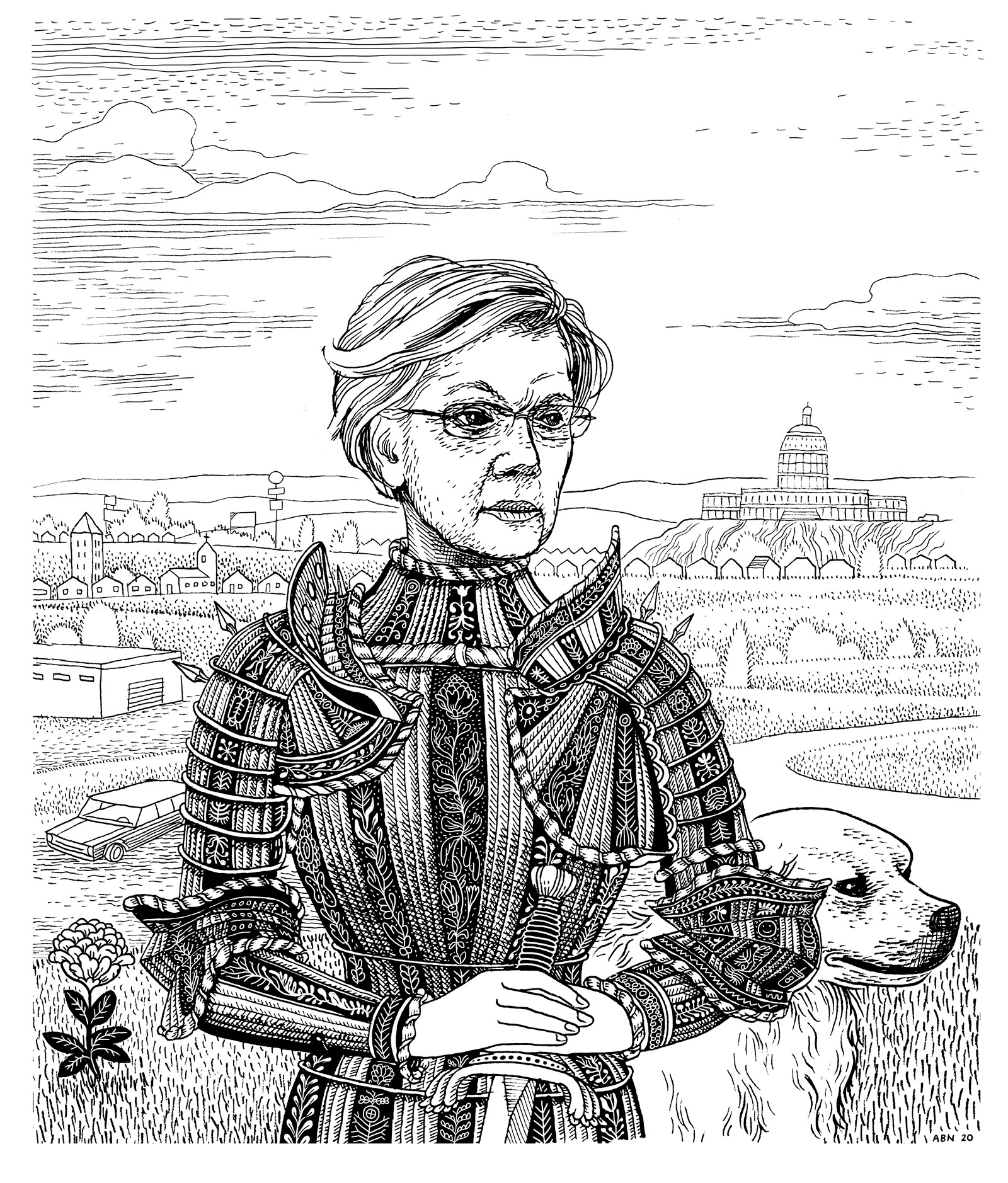

Since Elizabeth Warren’s formal announcement of her candidacy on February 19, 2019, the narrative about her has had little to do with her actual qualifications. From initially low poll numbers, she rode a brief upswing in October to the top of some national polls, immediately drawing a backlash, in part over concerns that her Medicare for All plan was too far to the left. After the debate on January 14, 2020, when Bernie Sanders denied having told her, at a private meeting in 2018, that he did not believe a woman could be elected, it was clear that the issue of “electability” swamped all else.

To anybody paying attention, however, that issue has been central since the beginning. In Warren’s rhetoric, in the media, and in voters’ reactions to her, perceptions of her have always been driven by gender. Again and again, in books, in stump speeches, and in response to voters’ repeated queries, she has emphasized that her qualifications as a “fighter”—she is constantly casting herself as one—were earned in the trenches of the gender wars.

In nearly 250 years of American history, a woman candidate has come this close to the presidency exactly twice, and in both instances, the woman has been running against Donald Trump. Given that Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by nearly three million votes in 2016 and still lost the election, the anguish in Democratic circles over a woman’s “electability” is legitimate, even as it’s deepened by atavistic fears. Yet Warren’s approach to handling blatant misogyny as well as the bias cloaked in pollsters’ lingo—“authenticity” and “likability” are among the terms—has lacked force and clarity. Although she was late to formulate her controversial support for Medicare for All, she has famously had a plan for just about everything: a wealth tax, student loan debt forgiveness, gun violence, criminal justice reform, climate change. But she seems not to have had a plan for tackling a form of bias entrenched for centuries. Indeed, at times, she has appeared to be running two races simultaneously—the real one, involving her actual positions, and an amorphous one involving an obsession with women’s gender differences.

In 2016 Clinton struggled to respond to charges that she was “cold,” “aloof,” and not “authentic,” bigoted code for being different, as in not male. This time around, Warren had a chance to shift the debate by comprehensively rejecting such coded language, challenging voters to confront the history, costs, and consequences of prejudice.

Briefly, she appeared to recognize the opportunity. When the issue broke out into the open in January, she said, “It’s time for us to attack it head on.” But she didn’t, instead employing a superficial zinger about having won every election she’s been in, unlike the men on the stage. Since then, she has insisted that “this is not 2016,” citing the women’s march and the 2018 midterms, in which women in both parties did, in fact, outperform men. But presidential elections are different, and between the January debate and the New Hampshire primary—and throughout her candidacy—Warren chose not to tackle the topic of sexism in any substantive way.

Warren’s personal story is a potent one, and, as with Hillary Clinton, her professional qualifications are not in question. Born in Oklahoma City, she grew up in poverty, won a debate scholarship to George Washington University, married at nineteen, and put herself through law school while raising two children, subsequently teaching at Rutgers, the University of Houston Law Center, and the University of Texas at Austin. She now lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is a national expert on bankruptcy and commercial law who has held endowed chairs at the University of Pennsylvania Law School and Harvard Law School. In the 1990s she became for a time the highest-paid professor at Harvard. She has two grown children from her first marriage and is on her second, to Bruce Mann, also a Harvard law professor. From 2010 to 2011, she served as special adviser to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, an agency she proposed under Obama, and was elected to the Senate in 2012, beating the popular Republican incumbent, Scott Brown.

Yet criticism of Warren, from tabloids to newspapers of record, is often ad hominem, referring not to her experience but to her manner. Despite her solid support in Massachusetts, and the enthusiasm engendered by her willingness to take selfies with long lines of fans and her surprise phone calls to voters, the Boston Herald has criticized her “self-righteous abrasive style” and “scolding self-righteousness.” When Warren appeared at the top of the polls, Bret Stephens, the New York Times Op-Ed columnist, enthused over a less popular woman candidate, Amy Klobuchar, finding Warren “intensely alienating” and a “know-it-all.”* At the same moment, David Brooks, another Times Op-Ed writer, said he’d hold his nose and vote for Warren if he had to, but found her “deeply polarizing.” A grown billionaire has wept over her vilification of deadbeat tycoons. (Warren responded by selling mugs emblazoned with the slogan “Billionaire Tears.”)

Advertisement

As its columnists dallied with retrograde attitudes, the Times newsroom reported on a range of biased responses in its coverage of electability, addressing issues of appearance (height and weight) and documenting the history of distaste for female voices. Early broadcast mikes, the paper noted, were designed for male voices and distorted the female voice so profoundly that women learned to alter their speech by lowering the tone, something Margaret Thatcher apparently did to project authority. More flagrantly, so did Elizabeth Holmes, former CEO of Theranos, the now defunct blood-testing start-up, whose siren call to the elderly white men she drew to her board of directors (George Shultz, Henry Kissinger, James Mattis, David Boies) involved pitching her speaking voice freakishly low. The majority of listeners complaining to NPR about newscasters’ voices are complaining about women and people of color.

Trump has a bizarre fixation on women’s mouths that seems related to this contempt for women’s speech, and it gives off a distinctly demeaning vibe. Since 2016, he’s been saying of Warren, “She’s got a fresh mouth,” a “big mouth,” and a “nasty mouth.” He expanded the preoccupation to Nancy Pelosi, claiming that her teeth “were falling out of her mouth and she didn’t have time to think!” He’d certainly like to close those mouths, and judging by the sexual assault allegations and defamation lawsuits against him, his orifice-related remarks are just one way of attempting to do so.

If you’re a woman, whatever your voice or appearance, you qualify for special forms of intolerance. Klobuchar plaintively compares herself, at five foot four, to James Madison (the same), because “height bias” is still a thing, with 58 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs topping out at six feet or over. As of 2019, thirty-three women led Fortune 500 companies—6.6 percent of the total. At Davos, women are sparse, and the World Economic Forum estimates that at current rates it would take 257 years to achieve gender parity in “economic participation.” There’s “second generation bias” in the workplace, reflecting a range of ways people unintentionally reward masculine traits (such as assertiveness) or networks, and “maternal wall bias”: a 2007 American Journal of Sociology study found that companies are significantly less likely to hire a woman who is a mother than a man or a childless woman. If they do, she’s likely to be offered $11,000 less than a childless female with similar qualifications. Progress has been so slow that California (among the most progressive states when it comes to diversity) recently enacted a law requiring public companies in the state to place at least one woman on their boards.

Warren reached the height of her popularity last fall, when she also pulled ahead of Biden in Iowa, a feat attributed in part to Biden’s weaker Iowa ground game and to a sense that she represented a sensible progressive alternative to Sanders. Roundly attacked by rivals in the October debate for not having a health care plan, Warren was preparing to announce her Medicare for All policy, costing $20.5 trillion over ten years. Even some of her supporters were taken aback by the plan’s daunting cost and legislative prospects, and she eventually refrained from referring to it in her speeches.

But in September, at the crucial moment of her greatest popularity and before the Medicare policy was announced, the Times and the Siena College Research Institute conducted the most extensive poll since the 2016 campaign of the six critical states carried by the president in 2016 (Arizona, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin) and found a seemingly unshakable prejudice against female candidates, held by men and women alike. In the November 5 episode of the Times’s podcast The Daily, Nate Cohn, a politics correspondent focusing on demographics, said that one reason for the poll was to correct for the kind of flaws that occurred in 2016, when Hillary Clinton was consistently found to be ahead. Trump, this later poll found, was still very competitive in those states, and Cohn was surprised to find that among frontrunners, Warren faced the most deficits:

Her results were worse than I thought they would be. The president led her in five of the six states. He led her in North Carolina and Florida by comfortable margins. He led in Michigan by a comfortable margin, even though Bernie Sanders was ahead there. She only led the president among registered voters in Arizona. And even that dissipated when you looked at the likeliest voters. So overall, she trailed by two points across these states among registered voters. That’s the same as Hillary Clinton’s performance. So if the election were held today, and if these results are right, Elizabeth Warren would lose to the president.

Not only were Warren’s left-of-center views and progressive support for Medicare’s expansion dismaying to voters. The poll examined underlying reasons, as Cohn described:

Advertisement

Six percent of voters told us that they would support Joe Biden against the president but would not support Elizabeth Warren in a head-to-head match-up against Donald Trump. And that 6 percent is going to be hard for her. We asked every one of these voters whether they agreed with the statement that Elizabeth Warren was too far to the left for them to feel comfortable supporting her, and a majority of them said they agreed with that statement. We also asked all of these voters whether they agreed with the statement that most of the women who run for president just aren’t that likable. And 40 percent of them said they agreed with that statement.

Such voters, the poll found, “have an unfavorable view of Warren by about a two-to-one margin.” One woman polled in Florida said:

“There’s just something about her that I just don’t like. I just don’t feel like she’s a genuine candidate. I find her body language to be off-putting. She’s very cold. She’s basically a Hillary Clinton clone.” And when asked about the women running for president more generally, she said, “They’re super unlikable.” So it actually turns out that among persuadable voters, women are a little likelier than men to say they agree that most of the women running for president are unlikable.

Anyone looking to understand why women may be more apt to discount candidates of their own sex need look no further than FiveThirtyEight’s “When Women Run,” a compilation of prejudices faced by more than ninety politicians. Knocking on doors, women candidates have repeatedly been asked, by other women, Who’s taking care of your kids? How can you run and take care of your family?

Acknowledging doubts about her “electability,” as Warren tentatively began to do after the January debate, does not appear to help. Deborah Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers, told the Times that doubt has now become “a self-fulfilling prophecy.” A woman knitting a pussy hat at a Warren event told a Washington Post reporter, “I love her, but she doesn’t really have a chance”; a man outside a Warren event (his wife and daughter were supporters) said he couldn’t imagine her on stage with the president, “as slightly built as she is, compared to a 245-pound Donald Trump,” as if debating were sumo wrestling. The success in New Hampshire of Sanders, a socialist, suggests that it’s not Warren’s left-of-center policies that are off-putting to voters.

In Rebecca Solnit’s endorsement of Warren’s candidacy in The Guardian, she claimed that Warren has “overcome misogyny,” praising her “Big Structural Mom Energy” (a play on Warren’s calls for “big structural change”) and “radical compassion.” But any overcoming has so far been limited by the all-too-evident glass ceiling. If you’re cooking up some “mom energy,” you can expect it to be spat out by a significant portion of the electorate.

That’s why nothing you read about Elizabeth Warren is really about Elizabeth Warren, including her own books about herself. In order to figure out who she really is, it helps to examine the relentlessly upbeat tenor of a self-image she has developed in reaction to low expectations. Her 2014 autobiography, A Fighting Chance, and recent stump speeches are festooned in pep club spirit and folksy blandishments, cloying bits of business that have attached themselves to her life story. Like Elizabeth Holmes’s voice alterations, these mannerisms are the product of long-fought constraints, suggesting the boxes that generations of women have found themselves in and the contortions adopted as a result, trying to appear smaller, less likely to offend, less likely to attract male disapproval and censure. What’s more: the linguistic stress positions that women have assumed to survive in a harsh environment are also meant to evade the concurrent shaming of women by women.

Female shaming, and accommodations made to it, lie at the center of Warren’s life. The facts are stark. She grew up in Oklahoma, a state synonymous since the Dust Bowl with rural desperation and poverty, something that would be, as Warren later put it, “a constant presence” in her parents’ lives. Donald Herring and Pauline Reed, his girlfriend, were both from Wetumka, a tiny town in east-central Oklahoma. Donald’s family owned the local hardware store and disapproved of Pauline, who was thought to have Native American ancestry on both sides of her family, a common (if largely untested) assumption among many in the state after its divisive history as Indian Territory. The two eloped in 1932 to a neighboring town, causing a permanent rift between the families.

By 1945, the Herrings had three boys, with Donald serving as a flight instructor at the army air fields at Muskogee; he later sold cars, carpeting, and fencing. Elizabeth, or Betsy as she was called, was born in 1949, and the family settled in Norman, south of Oklahoma City, taking out a mortgage on a small house in a new subdivision on the prairie. From the second grade, Betsy wanted to be a teacher, a goal her mother, a stern believer that women should be homemakers, strongly discouraged. When her daughter was eleven, Pauline convinced her husband to move to Oklahoma City so Betsy could attend a better high school, not for scholastic benefit, but so she could meet a middle-class boy to marry. On the strength of his Montgomery Ward sales job, Donald bought a second car, a used station wagon, for his wife.

Within a year of the move, disaster struck. Donald, at fifty-four, suffered a heart attack, and after hospitalization and weeks of recovery, demotion. The station wagon was repossessed, and Betsy watched as her parents began drinking, arguing over Donald’s inability to support the family. One day, as her daughter watched, Pauline, who had never worked outside the home, wrestled herself into a girdle and a black dress and walked to Sears, scoring a full-time, minimum-wage job taking catalog orders, saving the family from true privation.

In high school, Betsy began calling herself Liz. From the age of thirteen, she had been earning money babysitting and waitressing on weekends and summers in a restaurant owned by one of her mother’s sisters, Alice Reed, who lived in the back. “I saw first-hand the kind of commitment and energy it takes to launch a small business and to keep it going,” Warren would say later, noting that her aunt did everything from cooking to fixing appliances. “On the seventh day,” she recalled, in what was surely meant as a contrast with the Lord’s full day off, “we scrubbed floors on our hands and knees and got ready for the next week.”

Tensions between Liz and her mother exploded after her father’s health crisis. Excelling on the largely male debate team (while still scoring highest in her school on a test for the Betty Crocker Homemaker of Tomorrow), Liz wanted to apply to college, but her mother was vehemently opposed, denouncing her selfish ambition: “Why was I so special that I had to go to college? Did I think I was better than everyone else in the family?” Years later, Warren recalled retreating into silence, staring at the floor, trying to hide in her bedroom. Her mother followed, and the girl shouted to leave her alone. Pauline struck her in the face.

Throwing clothes in a bag, Liz ran to the bus station, where her father found her and sat with her, sharing his own struggles. Quietly, he took his daughter’s hand and told her to persist. “Life gets better, punkin,” he told her. She wrote later:

I carried that story in my pocket for decades. It was how I made it through the painful parts. Divorce. Disappointments. Deaths. Whenever things got really tough, I would pull out that story…. I’d hear my daddy’s voice, and I’d always feel better.

Running for president, Warren has pulled the story out of her pocket repeatedly, using her mother’s minimum wage job as an example of an era when Americans could support families on such an income. She has purged it of her mother’s defeatism, but those resentments still make themselves felt. In speeches, in a mawkish practice carried over from her autobiography, she constantly and warmly refers to “my daddy,” with the twang of a country singer. By comparison, Pauline Herring is referred to stiffly as “my mother,” and only rarely as “my momma.” While her affection for her father is clear, the unconscious animus toward her mother begins to establish another, distracting agenda.

She often introduces herself, as she did at Grinnell College in Iowa last November, by revealing that “I am what used to be called a late-in-life baby.” She stays with it, insisting that in her family, her brothers were always called “the boys,” but “my mother always just called me ‘the surprise!’” It’s her idea of a laugh line, and the audience does laugh, a little. But there are layers of discomfiture here. Aside from its irrelevance, the confession plays into yet another form of bias, the perception that women aren’t funny—because this isn’t funny. It’s more Sally Field than Fleabag, a plea for sympathy in which Warren compares herself with “the boys,” perpetuating a veiled sense of gender resentment. This too is an unforced error, and a minor one compared to the unfortunate Medicare roll-out or the completely avoidable claims to Native American heritage, which touched off Trump’s “Pocahontas” frenzy. But it’s too bad, since she’s capable of coming up with a deadpan comeback. (Asked how she’d reply to an “old-fashioned” supporter who favored marriage between a man and a woman, she said, “I’m going to assume it is a guy who said that. And I’m going to say, ‘Well, then, just marry one woman. I’m cool with that. Assuming you can find one.’”) Yet on the chaotic, inconclusive night of the Iowa caucuses, she was still playing the Okie card, declaring that “as the baby daughter of a janitor, I’m so grateful to be up on this stage tonight,” asking voters to overlook a Harvard career and lifetime of experience, and instead see her as daddy’s little girl.

“Fight” is a word she employs with numbing regularity. She used some version of it in her announcement speech twenty-five times. To donate to her campaign, text “FIGHT.” Her book titles sound like college football fight songs—A Fighting Chance and This Fight Is Our Fight. But for Warren, especially when it comes to sexism, talk of fighting has taken the place of actually fighting, which would mean confronting misogyny directly. When Barack Obama, arguably one of the most nimble and preternaturally gifted presidential candidates in American history, attacked racism in his pivotal speech in 2008, he took it seriously, analyzing it incisively and at length. The fight against misogyny will take far more than lip service or pinky promises or the use of slogans such as “Women win!”

Warren appears to fear what former Obama strategist David Axelrod calls her “lecturing,” said to be objectionable to white voters without a college education, and thus spends less time deploying her teaching skills and more indulging in cheerleading, couched in the apologetic, accommodationist pattern of women’s speech. This can be heard when she mentions her divorce and remarriage. Channeling Dr. Seuss, she calls her husbands H1 and H2, saying “Bruce, known as H2, I’ve held on to him and he’s a good guy! You bet!” But the pep rally vim only underscores the awkwardness professional women feel in trying to ingratiate themselves, struggling to be likable.

Warren is reportedly gifted at one-on-one meetings, and her legendary selfie lines are proof of the physical stamina and emotional flexibility that Sanders and Biden lack. But presidential campaigns are overwhelmingly public performances in which candidates must convincingly assume the mantle of leadership, working the levers of inspiration, excitation, and, on occasion, mass delusion. In that arena, Warren’s personal and autobiographical speeches contrast sharply with the brisker, policy-driven pitches of her male rivals. Springing to the podium to Dolly Parton’s “Nine to Five,” she’s the spunky gal from 1980s send-ups of sexism, recalling the day when her first teaching contract was not renewed when she became “visibly pregnant,” a line that elicits sympathetic groans from the audience. (It also inspired right-wing taunts and claims of exaggeration.) Her shorthand reference to her next pregnancy—“baby on hip, three years of law school, graduated visibly pregnant”—likewise harks back to the “barefoot and pregnant” tropes of an earlier time, inviting commiseration but not action.

Amy Klobuchar, whose campaign unexpectedly leapt ahead of Warren’s in New Hampshire, has argued the issue more effectively. She describes what she did in response to similar discrimination, citing her 1995 maternity ward ordeal, when she was asked to leave the hospital after twenty-four hours in compliance with insurance rules, even as her baby was suffering complications. A few months later, she brought six “visibly pregnant” friends to a Minnesota state hearing, successfully lobbying to end the hospital-stay limit.

Warren’s experiences are recognizable—no woman who remembers the 1970s could question them—and, for a certainty, her campaign is being held to a different standard. When a black man whose middle name is shared by a notorious despot ran for president, he too had to run an almost impossibly disciplined and flawless race. Whatever woman is going to win the highest office will have to display the same “ruthless pragmatism,” as Obama put it, that he brought to the job, the unswervingly calm, eloquent, uncompromising leadership that lays doubt to rest. The few women who have held on to long-term power across the centuries, from Elizabeth I to Margaret Thatcher and Nancy Pelosi, have always wielded that ruthlessness. When you’re in a knife fight, you don’t ask to be liked.

—February 13, 2020

This Issue

March 12, 2020

Foolish Questions

A Very Hot Year

Serfs of Academe

-

*

I was unable to find any instance in which Stephens referred to a man as a “know-it-all.” ↩