The French Revolution of 1789 astonished the world, and then came Napoleon Bonaparte, one of those rare historical figures who defined an epoch. The cascade of events between 1789 and Napoleon’s final defeat in 1815 gave birth to much of what we know as modern politics: revolution as a leap into the future, “right” and “left” as political markers, the notion of universal human rights, the extension of voting rights to most men, the “emancipation” of the Jews, the first successful slave revolt and the first abolition of slavery, not to mention the use of terror as an instrument of government and guerrilla warfare as a tactic of resistance, along with the police state, authoritarianism, and the cult of personality as ways of circumventing democratic aspirations.

Those are just the obvious political consequences of these upheavals. A dangerously unstable element was added in 1792: warfare that continued with little respite for twenty-three years. The fighting eventually touched virtually every continent and sea, took the lives of at least four million people and upended the existence of millions more, redrew national boundaries, led to the creation of new states, and struck fear into the hearts of every traditional ruler from New Spain (Mexico) to Java. France’s war with most of Europe unraveled the fragile democratic promise of 1789, as national security undermined rights at home and French aggrandizement abroad undercut any notion of liberating other peoples.

It is no wonder, then, that so many have tried to decipher the meaning of these events and that consensus about them remains elusive. Unlike its counterpart across the Atlantic, the first French republic has not attracted warmhearted biographies of its founding fathers because no one seems to fit the description. The French hero of the American War of Independence, the Marquis de Lafayette, at first supported the revolution but forsook his command of one of the French armies in 1792, then spent five miserable years in Prussian and Austrian prisons. The ardent republican Maximilien Robespierre argued against the death penalty and the practice of slavery and then justified the use of the new killing machine, the guillotine, against supposed enemies of the people whom he defined in ever broader terms. Napoleon, Corsican by birth and allegiance, established many important French institutions, from the Bank of France to the Legion of Honor, yet in the end he was forced to abdicate by his own handpicked officials.

While George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson all died in their beds, Robespierre was outlawed by his fellow deputies and guillotined, and Napoleon expired in exile more than four thousand miles from France. Lafayette survived to lead another revolution in 1830 against the restored Bourbons but was more celebrated in the United States than at home. Some seventy US cities and townships are named after him, yet the most impressive monument to him in France, located originally in the gardens of the Louvre but later transferred to a park along the Seine, was paid for by American donations and sculpted by a Connecticut-born artist at the beginning of the twentieth century. Napoleon considered Lafayette a “simpleton” who was “not at all cut out for the great role that he wanted to play.”

Rather than a scene of patriotic storytelling, the historiography of the French Revolution and Napoleon has been itself a battlefield. Constitutional monarchists and liberals favored the aspirations of 1789 and lamented the violence that came with the republic after 1792; socialists and then Communists focused more on 1792–1794, where they sought the sources of their movements; and after World War II, anti-Communists combed over the period 1789–1794 in order to show how democracy ended in totalitarianism.

A surprisingly large number of histories, from Jules Michelet’s seven volumes, published between 1847 and 1852, to Simon Schama’s nine-hundred-page Citizens of 1989, cover only the period from 1789 to 1794, as if the fall of Robespierre marked the end of what mattered and the five years that followed were somehow only a prelude to Bonaparte. Since Bonapartism had its own separate history in the nineteenth century, appealing neither to royalists nor republicans, it is perhaps not surprising that for many generations the history of Napoleon’s reign attracted an entirely different group of scholars who focused mainly on the man and his army.

A New World Begins by Jeremy Popkin and The Napoleonic Wars by Alexander Mikaberidze aim to break these molds by highlighting the connections between the French Revolution and Napoleon and by avoiding political partisanship. They succeed in bringing to bear a wealth of new scholarship to demonstrate, often in novel ways, the lasting significance of these episodes. A renowned expert on the history of the press and on the slave revolt that led to the creation of the new state of Haiti, Popkin incorporates the latest research on women, empire, plantation slavery, and the slaves themselves. Mikaberidze is better prepared than most to put the Napoleonic Wars into a truly global setting because he developed his fascination with Napoleon while growing up in the Caucasus and has written extensively about the Russian army during this period.

Advertisement

The two books dovetail with surprisingly little overlap because they concentrate on different periods. Popkin tells the story from the 1770s to December 1804, when Bonaparte crowned himself Emperor Napoleon, officially ending the republic. Stopping there means that Bonaparte has a peculiar status in Popkin’s account. He is in some ways just one of a multitude of riveting figures, and the wars that bring him to power are only one of many crises facing the revolutionary government. Popkin’s title suggests his focus on the revolutionary principles of the 1790s; the hope for a new world died a slow death as Bonaparte steadily dismantled liberty and equality in the name of order and stability. For Mikaberidze, Bonaparte is the main figure, and the years that precede his coup in 1799 serve as prologue. In this telling, the domestic politics of France take a back seat to international diplomatic and military challenges.

Both authors aim for balance when judging the actions of individuals. Mikaberidze necessarily highlights the decisions made by Napoleon, since the participants in the seven different coalitions against the French constantly shifted. He explicitly considers Napoleon a genius, and the word “dictatorship” hardly enters into his account. He argues that Napoleon’s seizures of territory resembled those of his opponents (Austria, Prussia, and Russia had not hesitated to annex portions of Poland between 1772 and 1795) and that his notorious blockade of the Continent to hobble British commerce followed from common eighteenth-century practices, including Britain’s barricade of all the major French ports between 1793 and 1799. He insists, in addition, that Great Britain bore just as much responsibility as Napoleon for the continuation of war after the brief peace of 1802.

The question of balance is trickier for Popkin because he has so many more characters to consider. He takes his motto from Louis-Antoine de Saint Just, the fiery young comrade-in-arms of Robespierre who was guillotined alongside him: “The force of things has perhaps led us to do things that we did not foresee.” Popkin applies the line to all sides, not just to the radical revolutionaries. He portrays Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, for example, as motivated primarily by their devotion to maintaining traditional institutions. The king’s greatest failing, it seems, was that he wanted to be loved by his subjects, and so in moments of crisis, he backed down. He could have ordered the deputies of the Third Estates arrested on June 23, 1789, when they refused to disperse on his order, but he did not. He could have more thoroughly fortified Paris with foreign regiments to prevent the uprising on July 14, but he stopped short. Instead, he went to Paris on July 17 and assured the people, “You can always count on my love.”

Right up to the end, Louis kept hoping that if he gave the impression of acceding to the deputies’ demands, he could carry on until they fell to squabbling among themselves and then gather up the pieces and rebuild monarchical authority. During the royal family’s flight to the northeastern border in June 1791, the king repeatedly stepped out of his carriage because he assumed that among the people far from Paris he would find countless loyal supporters. His dawdling proved fatal to the escape plan. Finally, in April 1792, he agreed to declare war on Austria, the land ruled by his brother-in-law, in the anticipation that even if the revolutionary armies prevailed, they would then follow their aristocratic commanders, march on Paris, and arrest the radicals.

There are no heroes or villains in Popkin’s narrative. The revolutionaries articulated enduring principles of liberty, equality, and democracy, but found it necessary to undertake draconian measures to defend them. Ordinary people could be roused to take extraordinary risks, such as storming the Bastille prison on July 14, 1789, but they could also vent their vengeance in horrific fashion, as they did in the September 1792 prison massacres in Paris. More than a thousand people were slaughtered, many of them hacked to death after summary judgments delivered by local militants. In the western region of France known as the Vendée, resistance to conscription and the reorganization of the Catholic Church ignited a civil war that pitted bands of peasants, sometimes led by nobles and aided by British money, against republican officials and soldiers. The rebels besieged towns and did not hesitate to kill, but in the end they had to retreat to a guerrilla-style conflict as government armies torched their fields and massacred entire villages in retribution.

Nowhere was “the force of things” more evident than in the colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), which in 1789 produced half the world’s supply of sugar and coffee with the labor of 500,000 slaves (at the time, the United States had 670,000). When the slaves revolted in 1791, the French first tried to repress the revolt, but they could no longer rely on the free blacks or mixed-race population, which was clamoring for rights, or even the white planters, who threatened to declare independence and align with France’s enemies.

Advertisement

The former slave Toussaint Louverture soon emerged as the rebellion’s military leader and signed up as a general for the Spanish when they promised freedom to those who helped them against the French. Louverture disapproved of the execution of Louis XVI and the attacks on the Catholic Church, yet he changed sides when the deputies in France finally agreed to the abolition of slavery in February 1794. The abolition had been declared by the commissioners originally sent to suppress the uprising when they saw that they could no longer maintain any semblance of French authority otherwise. In agreeing, the deputies in France were torn between fears that abolition was part of a British plot to destroy French commerce and hopes that abolition might encourage the slaves in the British colonies to rebel as well.1

Popkin’s invocation of the force of things is meant to circumvent the most partisan interpretations: that the slave revolt in Saint-Domingue was directed by abolitionists in Paris, that democracy in France was inherently totalitarian, or that the republic carried out a deliberate genocide against its own people in the Vendée. Popkin does not explicitly confront such polemics; he does not even hazard an estimate of the number of those who died in the Vendée rebellion, a subject of much heated discussion (the best estimates are 250,000 insurgents and 200,000 republicans). The artfulness of his narrative strategy militates against this kind of analysis. With amazing economy and grace, he interweaves all the various strands into one coherent story, including the revolt in Saint-Domingue, France’s war against much of Europe, political struggles in Paris, and a succession of uprisings not just in the Vendée but also in multiple places, from Caen in the north to Lyon and Toulon in the south. The reader therefore gets a remarkably clear sense of how events unfolded and of how unpredictable outcomes repeatedly changed the options available for everyone involved, even, and perhaps particularly, for Bonaparte.

By its very nature, however, a seamless storyline tends to obscure the joints that hold it together. Popkin ends up facing the same predicament that bedevils the people whose stories he tells; he sees how each major episode ineluctably shapes those that follow, but he cannot stand far enough back to detect the causes that drive the flow of events. The most glaring example of this is the weakness of the republic and its final collapse, which occurred in 1800, when Bonaparte established his supremacy, and not in 1804, when he declared himself emperor.

The fragility of the republic was preordained. The republic of the United States was feeble in the beginning, too, but it benefited from many advantages compared to its French counterpart: distance from Europe, no resident nobility, a ready refuge for dissenters in Canada, and an absence of alternatives. The French republic was surrounded by monarchs who were happy to sit by as thousands of French noble army officers crossed the border to organize a counterrevolution. The Vendée peasants who resisted conscription had no place to go, so they stayed and fought back. With centuries of royal rule etched in everyone’s memory, moreover, the republic could not erase the past just by devising a new calendar or changing names, especially since half of the population could not read newspapers or government decrees.

In this parlous situation, the army turned out to be the most effective school of republicanism in the short term, and it generated a series of outstanding officers in an astonishingly short period of time. But the more time the armies spent away from France between 1792 and 1799—in Belgium, Holland, the German and Italian states, Egypt and the Middle East, and colonies in the Indian Ocean and Caribbean Sea—and the more they relied on local goods and cash, the less loyalty they felt to the republic at home with its repeated rewriting of the constitution and constant upheavals in leadership. The soldiers’ allegiance shifted from the republic to the army and its commanders.

Although Popkin cannot stop his narrative long enough to provide explanations for the weakness of the republic or the involvement of the army in alternately forging and undoing it, he succeeds brilliantly at showing how the actual collapse was far from predestined. Bonaparte’s eventual co-conspirators would have preferred another, more pliable general, and when he secretly abandoned his army in Egypt and raced back to Paris in 1799, members of the government considered having him arrested. Then, on the decisive day in November, when he tried to bully the deputies into giving in to him, he swooned when he heard cries of “Down with the dictator!” and had to be saved by his brother Lucien. As president of one of the legislative assemblies, Lucien was able to convince the soldiers posted outside to intervene. Similar uncertainties shadowed the crucial months that followed, in which Bonaparte consolidated power that no one expected him to get. When it comes to showing how events can scramble the prospects of even the most determined plotters, Popkin has no equal, and readers will find in his pages a deeply satisfying account of the inevitable messiness of rapid change.

Since Mikaberidze’s focus is on war, it might be expected that he would devote much more space than Popkin does to the structures and practices of the French armies. In fact, neither of these excellent historians has much to say about military organization or battlefield strategies, much less about the experience of ordinary soldiers. Mikaberidze demonstrates the incredible reach of the Napoleonic Wars but does so by concentrating primarily on the diplomacy and geopolitical calculations that preceded and followed overt hostilities, rather than on the combat itself. He is determined to write a truly global history, and the Napoleonic Wars certainly lend themselves to that. Yet because he feels it necessary to give the back story of every theater, from the Americas to Asia, he must devote many pages to more general histories of the European great powers’ interactions with one another, with their colonies, and with non-European powers from Iran and the Ottoman Empire to China and Japan.

Many historians have been drawing attention to the global ramifications of the Napoleonic Wars, with much attention given recently to the formation of the state of Haiti and its consequences for the rest of the hemisphere. Mikaberidze builds on this work to offer his own reading. Napoleon only gradually came to support the reintroduction of slavery in what was then Saint-Domingue, but by 1802 he was ready to send off an expeditionary force to reestablish control that eventually numbered 40,000 men alongside two thirds of the ships of the French navy. Louverture was captured and sent to prison in France, where he died not long afterward. Despite using appallingly brutal tactics, the French forces could not overcome local resistance, and yellow fever carried off even the French commander, Charles Leclerc, a brother-in-law of Napoleon. As the French effort unraveled, Napoleon decided to sell the Louisiana Territory to the United States in order to keep it out of British hands. The size of the United States doubled, slavery expanded, and Native Americans faced even more catastrophic uprooting. The success of the Haitian rebels terrified slaveholders in the Caribbean and the United States, and in response white planters did everything they could to reinforce their domination.

Such entanglements, with their unintended consequences, could be found in every part of the globe, and Mikaberidze overlooks none of them, from the Latin American independence movements that were made possible by Napoleon’s invasion of Portugal and Spain in 1807–1808 to the less significant Nagasaki affair of the same period, in which a British frigate disguised as a Dutch trading ship penetrated the Bay of Nagasaki in an attempt to capture Dutch traders. The British captain forced the local Japanese to provision his vessel, thereby prompting, Mikaberidze argues, the effort of the Japanese to learn more about the outside world.

In this instance, Mikaberidze overreaches in his eagerness to show the influence of the Napoleonic Wars. While it is no doubt true that the British captain was pursuing British war aims by targeting Dutch traders (at the time, the Kingdom of Holland was ruled by Napoleon’s brother Louis), the impact of his intrusion was largely negative, because it strengthened Japanese determination to keep out foreigners. Japanese resistance to Western influence predated the Napoleonic Wars and lasted long after they were over; Commodore Matthew Perry did not sail into Tokyo Bay to force the opening of trade with the United States until 1853. The Napoleonic Wars did not cause everything that happened at the time or afterward.

Those wars did change many things for many people, however, and Mikaberidze’s well-informed and evenhanded account makes a truly impressive case for the extraordinary range of global disputes set in motion by them. It is perhaps understandable, then, that he leaves aside some big questions about Napoleon’s military leadership, the changing composition of the armies, and the underlying reasons for French dominance on the Continent over two decades. He concludes his brief description of the Battle of Austerlitz of 1805, at which the French defeated a Russian and Austrian army, with the assertion that it was “the masterpiece of Napoleon’s military strategy” but has little to say about that strategy. He mentions the innovations that are commonly cited: the corps system bringing artillery, cavalry, and infantry together in self-contained units that could move quickly on their own; the concentration of military and political authority in one man; and the establishment of a general staff to coordinate every aspect of a campaign. But it is the man who matters most; Mikaberidze does not hesitate to assert that the hero of his youth was “arguably the most capable human being who ever lived.”

The socially challenged young artillery captain did enjoy a meteoric ascent after reaching a low point in September 1795, when he was briefly removed from the list of officers for refusing to take up a post. As a scion of a minor Corsican noble family, he would never have been named commander of an army at age twenty-six under the former regime, and he was hardly alone in benefiting from the new order. More than two thousand men held the rank of general in the French armies during the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars; at the beginning of the war in 1792, nine out of ten generals were aristocrats, but by 1794 only two in ten were. Joachim Murat, the future king of Naples and brother-in-law of Napoleon, was the son of an innkeeper; Michel Ney, made a duke and then prince by the grateful emperor, was the son of a cooper; André Masséna, later made prince of Essling, was the son of a shopkeeper. As marshals of the empire, they had won fame and fortune because of their military prowess. Mikaberidze recounts their participation in various battles but says nothing about what their careers meant for them or for the army.

The French were able to maintain dominance on the Continent (the seas were another story) for three main reasons: their enemies failed to unite against them until 1813, Napoleon developed a successful diplomatic and military strategy of divide and conquer, and as commander-in-chief he kept the officers, in particular, on his side through an adroit use of propaganda, patriotism, and rewards, both monetary and honorific. Mikaberidze offers a very convincing account of the division of the allies and of Napoleon’s diplomatic skills. He says little about the esprit de corps of the army, however, which was crucial to Napoleon’s ability to keep fielding one, especially after the disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812. The word “propaganda” never comes up in relation to Napoleon, who was a master of it, both for home consumption and for the armed forces.

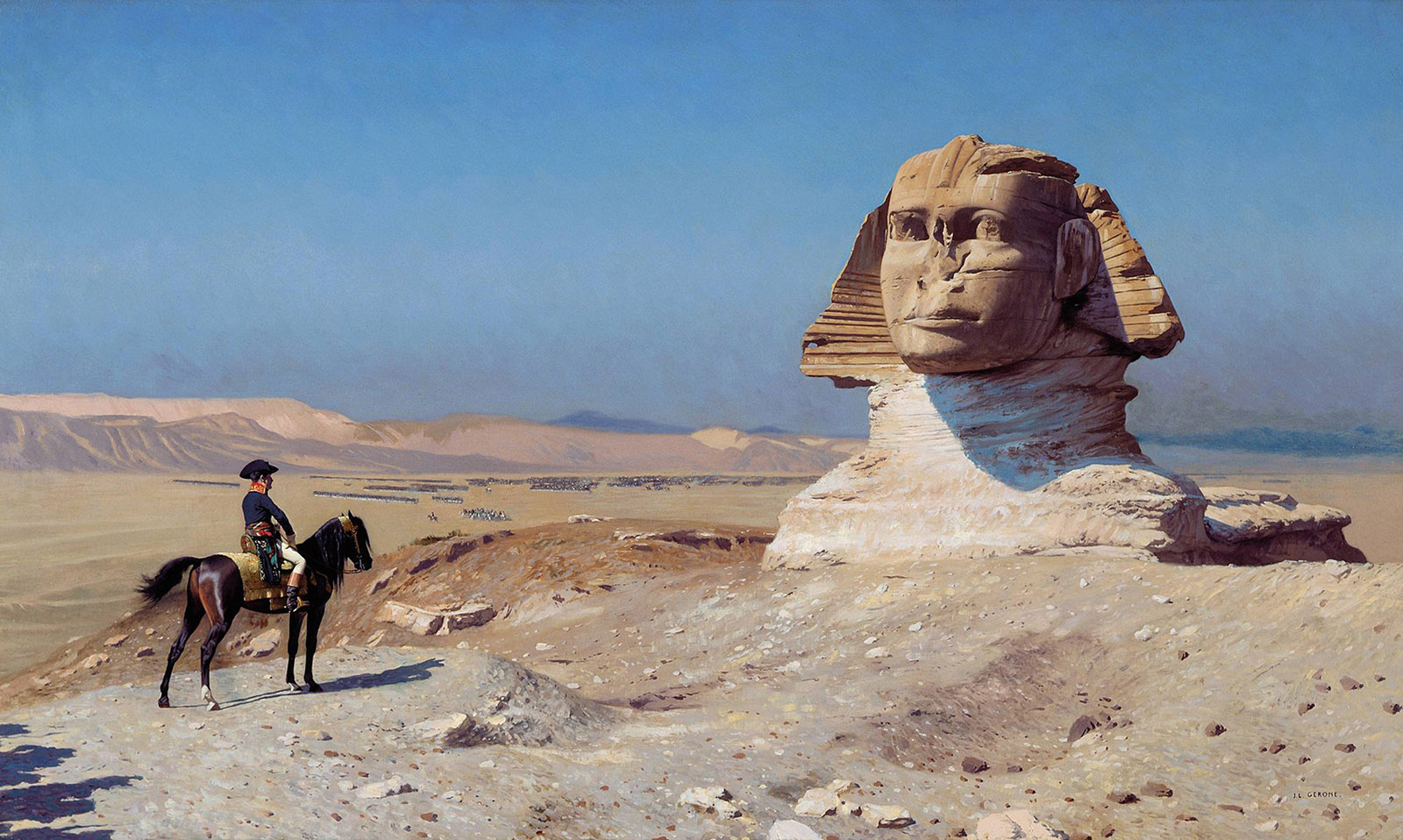

This lack of attention to the inner workings of the army and to Napoleon’s relentless image-making reflects Mikaberidze’s general lack of interest in cultural and gender issues, which are far from trivial in explaining wars. Morale is critical to any war effort, which means convincing women to support it, too. Napoleon used every means, from army bulletins he wrote himself to paintings and monumental arches, to impress the home audience and his soldiers with his personal bravery, charisma, and power.

Because the commander-in-chief and his officers had come up through the ranks, they had a ready rapport with ordinary soldiers. Napoleon always visited the troops before a battle, and excited cries of “Vive l’Empereur!” greeted him everywhere. He ordered displays of the prisoners, horses, and cannon that were captured in battle, and back home the art objects ripped out of German and Italian churches graced the Napoleon Museum—the newly renamed Louvre.

Napoleon infused French society with military values; the all-male students in his newly invented lycées wore uniforms and heard drum rolls rather than bells at the end of class. Values in the army also changed; the soldiers still fought for the nation but, over time, more for honor, manhood, and, of course, for Napoleon himself.2 What had been the school of the republic became the cradle of the Napoleonic legend.

This Issue

March 26, 2020

The Party Cannot Hold

Escaping Blackness

Left Behind

-

1

See David A. Bell, “The Contagious Revolution,” The New York Review, December 19, 2019. ↩

-

2

See Michael J. Hughes, Forging Napoleon’s Grande Armée: Motivation, Military Culture, and Masculinity in the French Army, 1800–1808 (NYU Press, 2012). ↩