As a teenager, I fell for Ayn Rand.

More precisely, I fell for her novels. Reading The Fountainhead at the age of fourteen, I was overwhelmed by the intensity and passion of Rand’s heroic characters. Who could forget the indomitable Howard Roark?

His face was like a law of nature—a thing one could not question, alter or implore. It had high cheekbones over gaunt, hollow cheeks; gray eyes, cold and steady; a contemptuous mouth, shut tight, the mouth of an executioner or a saint.

Roark was defined by his fierce independence: “I do not recognize anyone’s right to one minute of my life,” he says in the novel. “Nor to any part of my energy. Nor to any achievement of mine. No matter who makes the claim, how large their number or how great their need.” Like countless teenage boys, I aspired to be like Roark. And I found Rand’s heroine, Dominique Francon, irresistible. She was not only preternaturally beautiful—“she looked like a stylized drawing of a woman and made the correct proportions of a normal being appear heavy and awkward beside her”—but also brilliant, elegant, imperious, and cruel.

Enraptured by The Fountainhead, I turned immediately to Atlas Shrugged, Rand’s thousand-page morality tale about the titans of industry and other champions of capitalism, punctuated and propelled by love affairs. In her author’s note to that book, Rand explained, “My philosophy, in essence, is the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute.” Man as a heroic being! Reason as the only absolute! My adolescent self, frequently unreasonable and unsteady, was intrigued by those words.

In Rand’s operatic tales, the world is divided into two kinds of people: the creators and the parasites. The creator is “self-sufficient, self-motivated, self-generated.” He lives for himself. By contrast, the parasite “lives second-hand” and depends on other people. The parasite “preaches altruism”—a degrading thing—and “demands that man live for others.” Rand shows insidious parasites trying desperately to domesticate or enfeeble creators, who ultimately find a way to triumph by carving out their own path.

Rand’s narratives seemed to me to reveal secrets. She turned the world upside down. But after about six weeks of enchantment, her books started to make me sick. Contemptuous toward most of humanity, merciless about human frailty, and constantly hammering on the moral evils of redistribution, they produced a sense of claustrophobia. They were unremitting. They had too little humor or play. It wasn’t as though I detected a logical flaw in Rand’s writing and decided to embrace altruism, or that I began to like the New Deal and the welfare state. It was more visceral than that. Reading and thinking about Rand’s novels felt like being trapped in a small elevator with someone who talked too loudly, kept saying the same thing, and just wouldn’t shut up.

Decades later, I am struck by a puzzle. Rand’s impassioned, hectoring novels continue to resonate. They change lives. They seem to speak directly to some part of the human soul. Why? One reason is their clarity and confidence, the sense that they are onto hidden and suppressed truths. But that’s only part of it.

Published in 1943, The Fountainhead has sold over nine million copies worldwide. Atlas Shrugged, generally regarded as Rand’s most influential book, has done even better, with sales of about eleven million. Prominent politicians express admiration for her work. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has said that Atlas Shrugged “really had an impact on me.” Paul Ryan, the former Speaker of the House, once professed, “The reason I got involved in public service, by and large, if I had to credit one thinker, one person, it would be Ayn Rand.” Among billionaires, Steve Jobs, Peter Thiel, and Jeff Bezos have all called themselves fans. As her biographer Jennifer Burns puts it, “For over half a century Rand has been the ultimate gateway drug to life on the right.” Many people take her books as she intended, Burns writes, as “a sort of scripture.”1 Modern American politics, and the contemporary Republican party, owe a lot to Ayn Rand.

Lisa Duggan, a professor of social and cultural analysis at NYU, deplores Rand’s views, but she is fascinated by her. Duggan also thinks that Rand captures the current era. A point in her favor: President Donald Trump is a big Rand fan, and has said that he identifies with Roark. The Fountainhead, he claims, “relates to business [and] beauty [and] life and inner emotions. That book relates to…everything.” If we want to understand Trump, widespread current contempt for “losers,” and how the US Congress can enact tax reform that greatly increases economic inequality, Duggan thinks that we should focus on Rand, “whose dour visage presides over the spirit of our time.”

Advertisement

In her brisk new book, Mean Girl: Ayn Rand and the Culture of Greed, she offers at once a biography, a critical introduction, and an argument that Rand’s approach to freedom and capitalism has helped to fuel contemporary enthusiasm for free markets and social indifference to widespread inequality. Duggan offers a pointed account of Rand’s influence, which certainly fits with my own experience: She “made acquisitive capitalists sexy. She launched thousands of teenage libidos into the world of reactionary politics on a wave of quivering excitement.”

Rand was born Alissa Zinovievna Rosenbaum in 1905 in St. Petersburg, to a prosperous Jewish family. At the age of thirteen, she declared herself an atheist. (As she later put it, she rejected the idea that God was “the greatest entity in the universe. That made man inferior and I resented the idea that man was inferior to anything.”) When the Bolshevik revolution came in 1917, it hit her family hard. The pharmacy her father owned was seized and nationalized. Rand’s hatred of the Bolsheviks helped define her thinking about capitalism and redistribution. “I was twelve years old when I heard the slogan that man must live for the state,” she said, “and I thought right then that this idea was evil and the root of all the other evils we were seeing around us. I was already an individualist.”

The Bolshevik government shaped her future course, too, by exposing her to film. The Bolsheviks provided a great deal of support to the film industry, and Rand was enthralled by the potential of cinema and what she was able to see of Hollywood movies. In 1924 she enrolled in a state institute to learn screenwriting and decided to go to the United States, in the hopes of becoming a screenwriter and a novelist. She obtained a passport and a US visa, falsely telling a US consular official that she was engaged to a Russian man and would undoubtedly return. In 1926 she left Soviet Russia. She never saw her parents again.

Not long after arriving in New York, she changed her name to Ayn Rand. (How did she come up with that particular name? Over the decades, there has been a lot of speculation, but no authoritative answer.) Soon after moving to Hollywood, she managed to meet her favorite director, Cecil B. DeMille (it is not clear how); he hired her as a junior screenwriter. She also met Frank O’Connor, a devastatingly handsome, elegant, unintellectual, mostly unsuccessful actor, of whom she said, “I took one look at him and, you know, Frank is the physical type of all my heroes. I fell instantly in love.” She and O’Connor married in 1929. They lived in California, and she continued to work as a screenwriter. From the very beginning, she was the family’s breadwinner.

Rand’s writing career picked up in the 1930s, when she published her first two novels, We the Living and Anthem. (Rand enthusiasts regard both of them as classics.) Dismayed by the policies of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and by what she saw as broader collectivist tendencies in American life, she avidly read FDR detractors such as Albert Jay Nock and H.L. Mencken, who called themselves “libertarians.” (A small group of libertarians, who understood themselves as enthusiastic advocates of free markets and skeptics about state power, ultimately gave birth to an intellectual movement that has significantly influenced American politics.) Rand began to write in defense of capitalism. In 1941 she produced a statement of principles, “The Individualist Manifesto,” meant as an alternative to The Communist Manifesto. The principles echoed through her work for the rest of her life. A flavor:

The right of liberty means man’s right to individual action, individual choice, individual initiative and individual property. Without the right to private property no independent action is possible.

The right to the pursuit of happiness means man’s right to live for himself, to choose what constitutes his own, private, personal happiness and to work for its achievement. Each individual is the sole and final judge in this choice. A man’s happiness cannot be prescribed to him by another man or by any number of other men.

Written under the shadow of the manifesto and mostly in a one-year spurt of creativity, The Fountainhead was published in 1943. The book became a sensation, largely through word of mouth. Readers used words like “awakening” and “revelation” to describe their reactions. Rand became a celebrity. People wanted to meet her. Men, in particular, wanted to meet her. As Duggan puts it, “Rand’s attentions often wandered from her ‘hero’ Frank to an array of young men who visited her.” It is unclear whether her relationship with any of those men turned sexual, but there were serious flirtations and apparently romantic feelings. Her husband’s acting career was going poorly, and he was economically dependent on his wife; in many ways, their marriage represented a reversal of traditional sex roles. Rand wasn’t living the man-worship depicted in her novels.

Advertisement

After World War II, Rand became an anti-Communist cold warrior, testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee about the infiltration of the film industry, and of popular films, by communism. In 1944 she started to write Atlas Shrugged; it took her thirteen years to finish. In that period, Duggan reports, Rand withdrew from the political fray and relied on a small social circle, created for her by her most trusted acolyte, Nathan Blumenthal. Blumental was a handsome and vibrant Canadian who had long idolized her (and who was working as a part-time psychologist, using Rand’s principles). Twenty-five years younger than Rand, Blumenthal had read and reread The Fountainhead at the age of fourteen, memorizing whole passages. (Same here, as they say.) In high school and then as a student at the University of California at Los Angeles, he wrote fan letters to Rand. Initially she ignored them, but in 1950, she invited the nineteen-year-old undergraduate to visit her at her home.

Sparks flew when Blumenthal and Rand first met, at least by his own account. “I felt as if ordinary reality had been left somewhere behind and I was entering the dimension of my most passionate longing,” he later wrote. They talked philosophy from 8 PM that night until 5:30 AM the next morning, while O’Connor sat by in silence. Blumenthal describes himself as “intoxicated”—“two souls shocked in mutual recognition.” A few hours after the meeting, still early in the morning, he came to the apartment of his girlfriend, Barbara Weidman, also a Rand enthusiast. He was rapturous. “[She’s] fascinating,” he told Weidman, “she’s Mrs. Logic.” A few days later, Blumenthal returned to Rand’s home, this time with Weidman, who reported that she “was not a conventionally attractive woman, but compelling in the remarkable combination of perceptiveness and sensuality, of intelligence and passionate intensity, that she projected.”

Soon Blumenthal and Rand were speaking almost every evening, sometimes for hours. The two couples—Ayn and Frank, Nathan and Barbara—become close, even intimate. In 1951 Blumenthal and Weidman moved to New York, to study at NYU. Rand and O’Connor joined them a few months later.

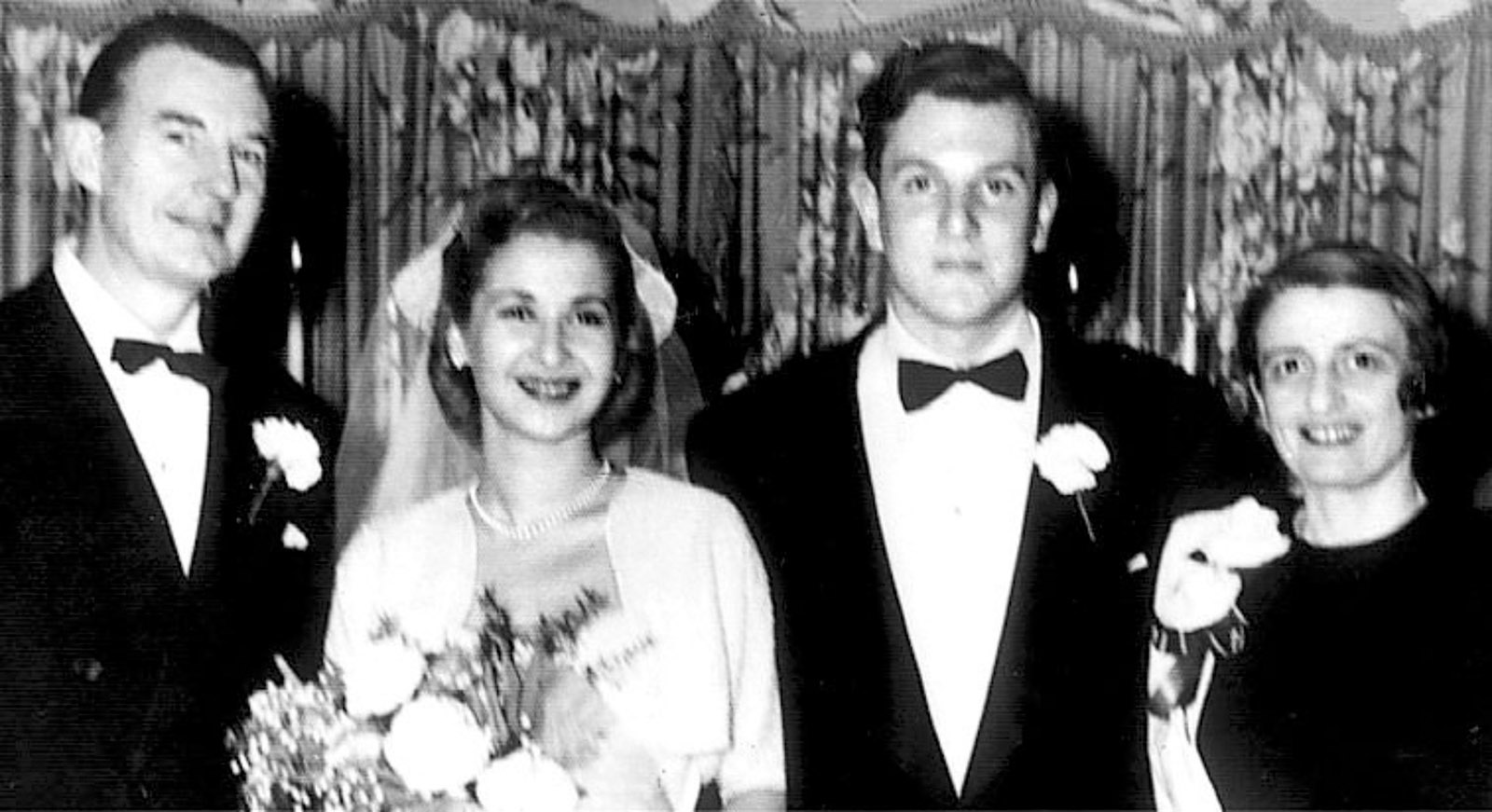

These were the founding members of what Duggan calls a “weird little group” that became “the base camp for Rand’s philosophical movement, Objectivism.” Things definitely did get weird, and began to take on aspects of a personality cult. Nathan Blumenthal, with Rand’s endorsement, decided to change his name to Nathaniel Branden, exclaiming, “Why should I be stuck with someone else’s choice of name?” In January 1953 he married Weidman, with Rand as maid of honor and O’Connor as best man. Barbara took the new last name, too.

In September 1954 Rand and Nathaniel Branden declared to their spouses that they had fallen in love with each other, and Rand, the supposed apostle of reason, calmly informed Barbara and Frank that their romantic connection was only rational. As Rand put it, “If Nathan and I are who we are, if we see what we see in each other, if we mean the values we profess—how can we not be in love?” But she promised that despite their feelings, their relationship would not be physical. “We have no future, except as friends,” Rand told Barbara and Frank. Predictably, their relationship did turn sexual.2 But Ayn and Frank stayed married, as did Barbara and Nathaniel. Throughout the period, Rand worked intensely on Atlas Shrugged; Frank and both Brandens read multiple drafts.

The book is dystopian science fiction, in which an imaginary US government has asserted unprecedented regulatory control over the private sector. Its first line signals a mystery: “Who is John Galt?” The country’s god-like creators (inventors, scientists, thinkers, architects, and others who do and make things), led by Galt, a Roark-like hero, decide to go on strike. They withdraw from society and watch the parasites and the looters devour themselves. As Duggan puts it, Rand depicts the creators “as sexy, gorgeous, brilliant, and thoroughly admirable heroes, as contrasted with the flabby, unattractive, incompetent, unproductive moochers and state-backed bureaucratic looters, parasites, and thugs.” Ultimately the government collapses, and Galt plans to create a new society, based on principles of individualism. The final sentence of Atlas Shrugged captures Galt in a moment of mastery: “He raised his hand,” Rand writes, “and over the desolate earth he traced in space the sign of the dollar.”

Rand dedicated her book to two people: her husband and Nathaniel Branden. Of Branden, she wrote:

When I wrote The Fountainhead, I was addressing myself to an ideal reader—to as rational and independent a mind as I could conceive of. I found such a reader—through a fan letter he wrote me about The Fountainhead when he was nineteen years old. He is my intellectual heir. His name is Nathaniel Branden.

Rand predicted that Atlas Shrugged (published in 1957) would “be the most controversial book of this century; I’m going to be hated, vilified, lied about, smeared in every possible way.” The early reviews were indeed horrific. The most severe came from the pages of the National Review, where Whittaker Chambers, the ex-Communist and conservative hero, deplored her atheism and proclaimed:

Out of a lifetime of reading, I can recall no other book in which a tone of overriding arrogance was so implacably sustained…. From almost any page of Atlas Shrugged, a voice can be heard from painful necessity, commanding: “To a gas chamber—go!”

Nevertheless, the book became a national phenomenon. But Rand was devastated. She craved approval not from ordinary readers but from leading intellectuals and prominent thinkers, including academics, and she didn’t get it. She fell into a deep depression, telling the Brandens, “John Galt wouldn’t feel like this.” (That’s funny, but she didn’t mean it as a joke. Rand didn’t do self-deprecation.) She never wrote fiction again. Nathaniel Branden became a vigorous entrepreneur on her behalf, organizing various lecture series on Objectivism, and ultimately creating, in 1958, the Nathaniel Branden Institute (NBI) in homage to her. Several years later, the Brandens separated, but they continued to work closely together as, in Barbara’s words, “comrades-in-arms.” They succeeded in producing something like an organized movement, with 3,500 students in fifty cities by 1967. The NBI, and Rand’s social world, revolved around what she called the Collective, a small group of devotees (including Alan Greenspan, who went on to become chairman of the Federal Reserve Board).

But something was rotten in the state of NBI. There was secrecy—the organization was led by Rand and Branden, whose passionate, turbulent relationship was known to their spouses, but hidden from everyone else—and there was enforced orthodoxy. Within the Collective and the NBI, Rand and Branden would not tolerate the slightest dissent. As Branden wrote in his memoir, with a kind of mordant humor, students were taught the following:

• Ayn Rand is the greatest human being who has ever lived.

• Atlas Shrugged is the greatest human achievement in the history of the world.

• Ayn Rand, by virtue of her philosophical genius, is the supreme arbiter in any issue pertaining to what is rational, moral, or appropriate to man’s life on earth.

In 1968 things fell to pieces. Rand abruptly split with the Brandens, stating in a bizarre public letter, “I hereby withdraw my endorsement of them and of their future works and activities. I repudiate both of them, totally and permanently, as spokesmen for me or for Objectivism.” Though she referred to various financial and personal improprieties, she did not disclose the actual reasons for the split. Both Brandens responded with public letters of their own. Neither revealed the truth, which was intensely personal. While working closely with Rand and continuing to proclaim his love for her, Nathaniel had ended their sexual relationship, citing supposed psychological problems (for which she “counseled” him). All the while, he was having a secret love affair with another woman. He disclosed that relationship to Barbara as early as 1966; after repeated entreaties from Rand, asking what on earth was wrong with Nathaniel, Barbara told her the truth.

Rand was shattered. Branden, she told Barbara, had taken away “this earth.” She also fell into an implacable rage, which lasted for the rest of her life. She never spoke to Nathaniel Branden again. Barbara put it this way to Nathaniel: “Ayn wants you dead!” Among other things, she ordered the deletion of her glowing words about Nathaniel in the dedication of Atlas Shrugged.

Though Rand did not fully recover from the emotional devastation, she continued to work and to write. She spoke on college campuses, and she did interviews on television, where she was often engaging, charming, and even funny. She wrote long essays for The Objectivist magazine and the Ayn Rand Letter.

In the early 1970s, her health deteriorated. A lifelong smoker, she was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1974. Five years later, Frank O’Connor died, a second blow. Rand died in 1982. By that point, she had alienated or rejected most of her friends.

Duggan is interested not only in Rand’s extraordinary life but also in her influence on contemporary politics and in particular the rise of neoliberalism, which, she says, seized “state power by the 1980s.” Duggan does not clearly define neoliberalism, but she describes it as a “global anti-left social movement,” focused on reducing taxes and regulation. She associates it with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, but also, and in more moderate form, with Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, and Barack Obama. Its point “was to free capitalism” and promote “privatization of public services” and “erosion of consumer and workplace protections.” Duggan thinks that neoliberalism was, in significant part, a product of resistance to the civil rights movements in the United States, and that it marched under the name of “property supremacy.” In Duggan’s account, “Rand’s influence floats” over neoliberalism “as a guiding spirit for the sense of energized aspiration and the advocacy of inequality and cruelty.” Neoliberals see the powerless not as “a class, but a collection of individual failures.” By contrast, the rich are, in their view, “the very source of wealth and a boon to society.” That happens to be the central argument of Atlas Shrugged.

After the crash of 2008, Rand had a revival; her books have been selling astonishingly well. Atlas Shrugged reportedly sold 500,000 copies in 2009, more than doubling the previous record, established the year prior. In some respects, the age of Trump can be seen as the age of Rand. Duggan is careful to emphasize that

Trump is in most ways a Rand villain—a businessman who relies on cronyism and manipulation of government, who advocates interference in so-called “free markets,” who bullies big companies to do his bidding, who doesn’t read.

Trump is anything but a self-made man, and he is hardly a consistent proponent of capitalism as Rand defended it. But “his cabinet and donor lists are full of Rand fans.” Far more important, some of his policies are unmistakably Randian: tax cuts, especially for the wealthy; elimination of safeguards for consumers and workers; repeal of important environmental regulations. As Duggan sees it, Rand “is the avatar of capitalism, in its militant form as market liberalism.” She urges people to “reject Ayn Rand.”

Duggan is less than sure-footed in her lamentations about neoliberalism; Obama doesn’t fit easily in the same category as Reagan (look at the Affordable Care Act, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the Paris accord on climate change). But she is sharp, engaging, and funny when writing about Rand, whose magnetism, determination, grandiosity, desperation, and galloping narcissism Duggan captures beautifully. As she notes, Rand influenced contemporary political thought less because of her ideas than because she offered, in The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, heroic accounts of capitalism and capitalists, and contrasted them with the losers, the moochers, and the “second-handers” who seek to steal from them through taxes and regulation. As a result, she gave voice to, and helped spur, a specifically moral objection to redistribution of wealth and interference with property rights and market arrangements. That objection resonates strongly in the business community and the Republican Party, and something like it certainly has advocates in the Trump administration.

Was Rand a serious thinker? That is doubtful. She did not defend her conclusions so much as pound the table and insist on them. (From a passage in The Fountainhead defining freedom: “To ask nothing. To expect nothing. To depend on nothing.”) Yet she did write a great deal of nonfiction attempting to justify Objectivism in strictly philosophical terms. Robert Nozick, the influential libertarian philosopher, seemed to take her seriously, and the Ayn Rand Society, affiliated with the American Philosophical Association, produces papers and books focusing on her work. But if one is interested in free markets, liberty of contract, and the importance of private property, one would do a lot better to read Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, or Nozick himself.

Duggan convincingly shows that Rand’s enduring influence comes from the emotional wallop of her fiction—from her ability to capture the sheer exhilaration of personal defiance, human independence, and freedom from chains of all kinds. With her novels, Rand identified, touched, and legitimated the psychological roots of a prominent strand in right-wing thought. A skeptic about Roark’s ambitious plans poses this question to him: “My dear fellow, who will let you?” Roark’s answer: “That’s not the point. The point is, who will stop me?”

That exchange captures the attitude of many people who want to do away with social programs like the Affordable Care Act, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Clean Air Act, even the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Call it Who-Will-Stop-Me Capitalism. It has special resonance among adolescent boys, but its appeal is much broader than that. The problem is that those who need to lionize men with “a contemptuous mouth, shut tight, the mouth of an executioner or a saint” tend to be terrified of something. Altruism really is okay. Redistribution to those who need help is hardly a violation of human rights.

Rand had a unique talent for transforming people’s political convictions through tales of indomitable heroes and heroines, romance, and sex. Duggan describes her novels as “conversion machines that run on lust.” Nearly a decade after Rand’s death, Branden seemed to agree, writing that “not just Ayn and me, but all of us—we were ecstasy addicts. No one ever named it that way, but that was the key.”

This Issue

April 9, 2020

Bigger Brother

Stuck

In the Time of Monsters

-

1

See Jennifer Burns, Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (Oxford University Press, 2009). ↩

-

2

Nathaniel Branden’s Judgment Day: My Years with Ayn Rand (Houghton Mifflin, 1989) is a riveting account, lurid and full of insights. Excellent biographies, offering far more detail than Duggan does, are Anne Conover Heller, Ayn Rand and the World She Made (Nan A. Talese, 2009), and Burns’s Goddess of the Market. ↩