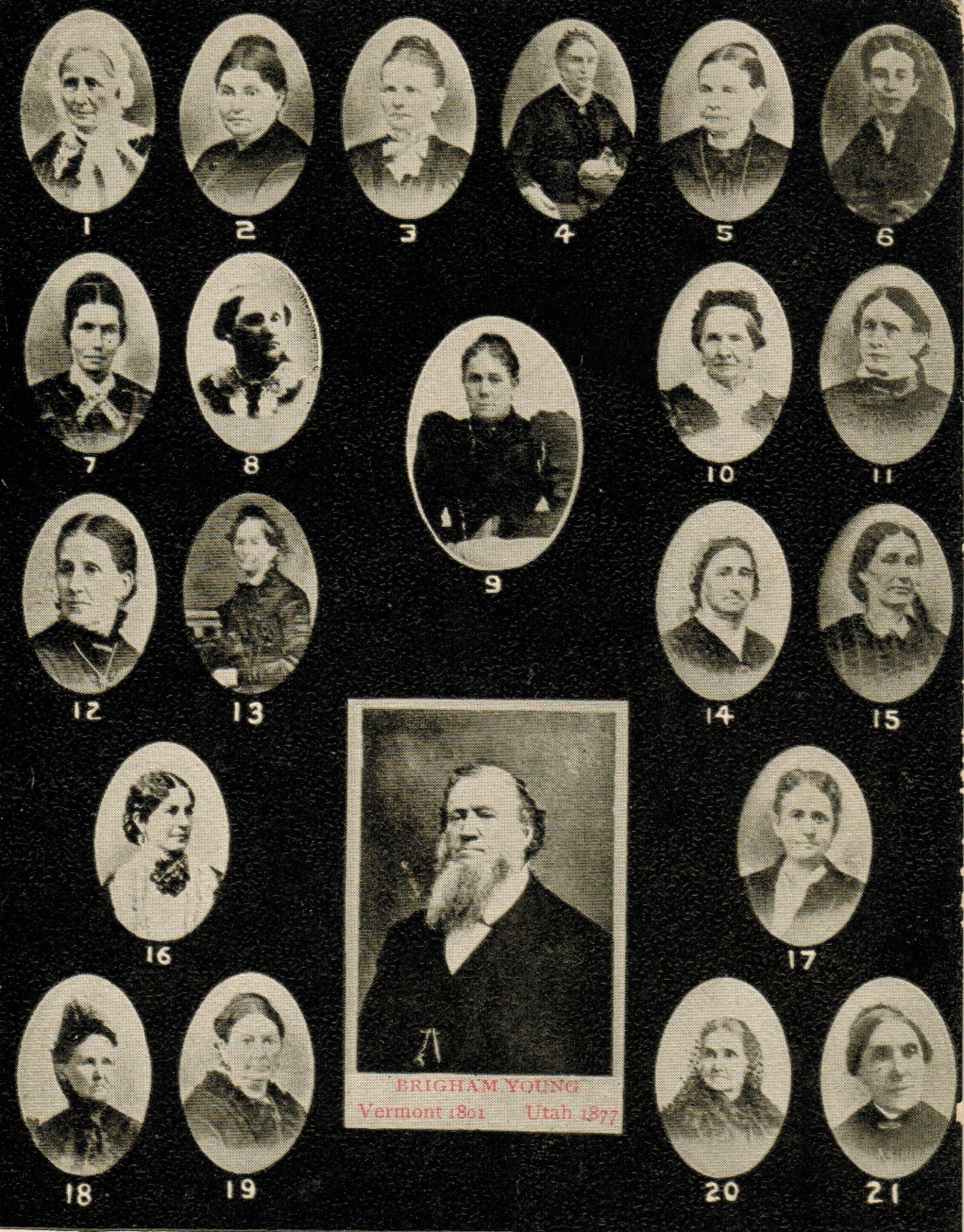

The Mormon leader Brigham Young had more than fifty wives. Many of them lived in adjacent homes, the Beehive House and the Lion House, in Salt Lake City, which Young founded in 1847 as the president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Polygamy, which the Mormons publicly announced as a church doctrine in 1852, provoked responses ranging from outrage to amusement among many Americans. Numerous anti-Mormon exposés appeared, with titillating titles like Awful Disclosures of Mormonism and Wife No. 19, or, The Story of a Life in Bondage. Bawdy jokes circulated, like this one from a comic newspaper: “Brigham Young cannot be said to rule with a rod of iron, as he emphatically enforces his commands by a pole of flesh! It is hard, no doubt, but not fatal.”1

Mormon polygamy was no laughing matter, however, for the Republican Party, which emerged in the 1850s with the aim of stamping out, its 1856 platform declared, “those twin relics of barbarism—Polygamy and Slavery.” Republicans insisted that polygamy and slavery (Young believed in both) destroyed individual freedom, the former by trapping women in patriarchal plural marriages, the latter by holding blacks in bondage. During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln signed into law the first of several anti-polygamy laws that, over time, put so much pressure on the LDS church that it banned the practice in 1890 (though some fundamentalist Mormons continued it thereafter, including thousands who escaped the government crackdown by moving to Mexico, as the massacre in November 2019 of a Mormon family there reminds us).

Why did the Mormons and other groups adopt a form of marriage that was as controversial and as distant from mainstream mores as polygamy? What was it like to be part of a polygamous marriage? How do polygamous communities relate to the larger society?

Sarah Pearsall addresses such questions in her well-researched, often engrossing Polygamy: An Early American History. She has interesting things to say about the Mormons, though much of her book is devoted to exploring earlier examples of polygamy in North America. Pearsall traces plural marriage from sixteenth-century Guale Indians in Florida and seventeenth-century Pueblo Indians in New Mexico through Algonquins in New France (later Canada) to the Pequot, Wampanoag, and Narragansett tribes in southern New England and, in the South, the Cherokees, who were in time forcibly removed to Oklahoma. Interspersed with the discussions of these Native Americans is an account of polygamy among West Africans, some of whom continued the practice when they were transported to America as slaves.

Pearsall shares the interest of many current historians in the lives and cultures of marginalized groups that were once largely ignored by scholars. One of her themes is power. She reveals that polygamy was an empowering force for men and, in a number of instances, for women. Among the Guales and Pueblos, polygamy was a bold gesture of rebellion against Franciscans from Spain who tried to force Roman Catholic monogamy on them. There were significant differences, Pearsall shows, between polygamy among the two tribes. The Guales reserved it for the social elite, for whom it was a sign of status and social control. The Pueblos, on the other hand, made efforts to democratize polygamy, which was offered as a reward for exceptional military service. The Pueblo leader Po’pay (or Popé) tried to make plural marriage widely available among his followers, favoring what Pearsall calls “populist polygamy”—a cultural assertion of independence that fed into the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, in which the natives succeeded in driving the Spaniards from their territory.

The other indigenous peoples Pearsall investigates also used polygamy as a weapon of resistance. One Algonquin leader accepted all aspects of Catholicism except monogamy—he refused to give up his multiple wives, despite vigorous pleading by French priests who had settled in their region. The case of the Algonquins shows that polygamy, like early America itself, could be “squalid and brutal,” in Pearsall’s words. The Algonquins came down severely on wives who strayed. A husband and his other family members held the power of life and death over a wife. A traveler reported, “If any Woman defile her Marriage-bed, the Husband cuts off her Nose, or an Ear, or gives her a flash in the Face with a stone Knife; if he kill her, he is clear’d for a Present which he gives to her Parents to wipe away their tears.” Some tribes in the Algonquin nation punished adulterous wives by subjecting them to gang rape.

One of the most thought-provoking sections of Pearsall’s book is its discussion of seventeenth-century New England. She points out that polygamy posed a conundrum for Puritan settlers. They prided themselves on following the dictates of the Bible and saw their mission in the New World as a fulfillment of scriptural mandates. They could not overlook the commonness of polygamy in the Old Testament, according to which Solomon, for example, had seven hundred wives and three hundred concubines. Abraham, Moses, David, Saul, and other biblical patriarchs were also polygamists.

Advertisement

As a result, some Puritans argued that polygamy was divinely sanctioned. In England, the Puritan poet John Milton wrote, “Polygamy is either marriage or else it is whoredom or adultery…. Let no one dare to say that it is whoredom or adultery—respect for so many polygamous patriarchs will, as I hope, stop him!” New Englanders, however, followed other Protestant thinkers, such as William Ames, who reached back before the patriarchs to Adam and Eve. Ames, who called polygamy a “sinne against the law of nature and right reason,” emphasized that “God made one man and one woman, and not one man and two women.” This was the doctrine accepted by New Englanders like the Reverend John Cotton, who dismissed Old Testament polygamy as merely a “sinne of ignorance” on the part of the patriarchs. New Englanders not only promoted monogamy but also inflicted harsh punishment on any form of sexual aberration: an adulterer, for example, was usually whipped, while one who committed sodomy could be executed.2

Even as the Puritans took a conservative stance on sexuality, Native Americans in their midst strengthened their commitment to their long-running practice of polygamy, which permitted native families to operate with efficiency and hospitality, since everyday duties were typically shared by the wives of a sachem. Mary Rowlandson, the Massachusetts woman who in 1675, during King Philip’s War, underwent the excruciating ordeal of being held captive by Native Americans for more than eleven weeks, actually expressed appreciation in her autobiographical narrative for the aid she received from one of the three wives of her captor, the Narragansett sachem Quinnapin.

Pearsall demonstrates that some enslaved Africans practiced polygamy. In West Africa, many tribal leaders were polygamous. The early-eighteenth-century Dutch traveler Willem Bosman found that polygamy, considered a sign of prestige, was “common among the Negroes…. They place their Glory in it…. They can’t depart from it.” He reported that in one country, men had “forty or fifty [wives], and their chief Captains three or four Hundred, some one Thousand, and the King betwixt four and five Thousand.” When kidnapped and sold into slavery in America, most West Africans were prevented from keeping a family, but in certain cases retained their wives from their pre-captive families. Some enslaved men who earned the trust of their managers, overseers, or masters were permitted to be married, in some cases to more than one wife.

As Pearsall points out, polygyny (a man having many wives) has been far more common in American history than polyandry (a woman having many husbands). But there have been exceptions. A form of polyandry, aptly called complex marriage, was practiced from 1848 to 1880 at John Humphrey Noyes’s religious community in Oneida, New York, where monogamy was deemed sinful and group marriage was thought to usher in the millennium.3 Every woman in the community was considered to be married to every man. Older members of the group had intercourse with young ones in order to introduce them to sex; Noyes initiated girls as young as twelve or thirteen. Not only was variety in sexual pairings encouraged, but men practiced coitus reservatus—the withholding of ejaculation—in order to avoid unwanted pregnancies and give maximum pleasure to women.

The Mormons, in contrast, not only wanted to reproduce their kind but also saw polygamy, surprisingly, as a means of cultivating female purity. Pearsall gives the example of Belinda Hilton, a New England woman who in 1844 abandoned her husband and entered into a plural marriage with Parley P. Pratt, a prolific Mormon pamphleteer and an elder in the LDS church who eventually had twelve wives and thirty children. Among his 30,000 to 50,000 descendants are Mitt Romney and Jon Huntsman. Belinda, Pratt’s sixth wife, not only embraced polygamy but promoted it zealously. She wrote a pamphlet, Defence of Polygamy, by a Lady of Utah, that gave four justifications for plural marriage as practiced by the Mormons: theological, natural, social, and familial. She emphasized not only that the Old Testament patriarchs were polygamous but also that they received the blessing of Jesus, who declared, “And I say unto you, That many shall come from the east and west, and shall sit down with Abraham, and Isaac, and Jacob, in the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 8:11).

Not only was polygamy holy, Belinda wrote, but it accelerated “the multiplying of our species,” thereby fulfilling the Bible’s injunction to be fruitful and multiply. At the same time, she argued, Mormon polygamy nurtured chastity, since the church discouraged pregnant women from having sex. Pursuing this argument, Belinda insisted that there were “no adulteries, fornications” in polygamous marriage, which kept women away from wily seducers who brought on “female ruin”—her response to a prudish nineteenth-century American culture in which a single woman known to be “fallen” (that is, engaging in premarital sex) was likely to be ostracized or driven to prostitution. Belinda’s final justification—familial—referred to the shared parenting and mutual affection that bonded the “sister wives” in a plural marriage. “Polygamy,” Belinda concludes, “leads directly to…sound health and morals in the constitution of their offspring.”

Advertisement

Pearsall, who writes that “Belinda’s defense of polygamy is eloquent, earthy, and passionate,” comes close to offering a feminist justification for polygamy on the grounds that it provided a liberating space for women. To be sure, at one point she mentions its shortcomings, noting that “polygamy has had so many disadvantages for women that they hardly need rehearsing. It seems uniquely patriarchal and unfair to wives, all of whom are supposed to serve the husband.” But she calls attention to the drawbacks of monogamy, too: “Monogamy—not polygamy—might mean isolation, separation from family and kin into a husband’s community, and exhausting domestic burdens for a woman to juggle all on her own.”

Her point certainly applies to many marriages in pre–Civil War America. In most states, a woman entering marriage surrendered her property and her legal rights to her husband. Since divorce was generally difficult to procure, women were often forced to suffer for long periods at the hands of abusive husbands. The inequities of middle-class marriage were noted at the 1848 Seneca Falls women’s rights convention, which issued a Declaration of Sentiments that said of the wife, “In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her master—the law giving him power to deprive her of her liberty, and to administer chastisement.”

In light of the oppressiveness of nineteenth-century monogamous marriage, Pearsall calls attention to the relative freedom and same-sex bonding that Mormon polygamy made possible for some women. She notes that the LDS church facilitated divorce for wives who found themselves unhappy in plural marriages. Also, in 1870, fifty years before the Nineteenth Amendment guaranteed suffrage for American women, the territory of Utah gave women the vote.

In exploring such positive aspects of polygamy, Pearsall, who teaches early American history at the University of Cambridge, follows the lead of Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, her former adviser in the doctoral program at Harvard. Ulrich, whom she acknowledges as “my awe-inspiring teacher and friend,” strikes a similarly feminist note in her book A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835–1870 (2017). Ulrich describes the challenges for women within plural marriages but also the benefits. Although Brigham Young’s home was called by outsiders a “harem,” Ulrich writes, “it could also have been described as an experiment in cooperative housekeeping and an incubator of female activism.”

This is a worthwhile line of thought, but one should not forget just how patriarchal Mormon polygamy was. Young advised women to “not ask whether you can make yourselves happy, but whether you can do your husband’s will, if he is a good man.” He explained, “Let our wives be the weaker vessels, and the men be men, and show the women by their superior ability that God gives husbands wisdom and ability to lead their wives into his presence.” Another Mormon elder, William W. Phelps, instructed one of his wives to “keep your husband’s commands in all things as you do the Lord’s. Your husband is your head, and the Lord is his head.” He assured his wife that “as I love you, so I will chasten you, if you step aside from what I require, and what I know is the will of the Lord.” This doctrine did not sit well with some women, as indicated by the fact that at least eight of Young’s wives divorced him.

Pearsall, seeking to differentiate early Mormon polygamy from similar practices in recent times, writes, “This book is not a polemic for polygamy, and the forms of it that exist today are on the whole deeply troubling.” She does not specify which recent polygamists she has in mind, but presumably she means figures like Warren Jeffs, the fundamentalist LDS leader who was convicted in 2011 of child sexual assault and is serving a life sentence. Actually, though, he could sound much like Brigham Young, as when, in court documents submitted in his defense, he enjoined women “to obey your husband in all things in righteousness” and “build up your husband by being submissive.”

It would have been illuminating if Pearsall had applied her impressive research skills to describing the religious background of Mormon polygamy. Young’s polygamous predecessor, Joseph Smith, who founded Mormonism, was a product of his time. As a young man in the “Burned-Over District” of upstate New York, Smith was fired up by a Methodist revival and soon believed that he was directly in touch with the divine. An angel, Moroni, allegedly gave him golden plates inscribed with a strange language that Smith translated into English by using special glasses. This text became the Book of Mormon, which announced that America would be the main venue for the reappearance of Christ and that American “saints” must prepare the way for the Second Coming. Among the biblical practices revealed to Smith was polygamy. He “sealed” himself with as many as forty wives, and many other Mormon elders followed suit.

Pearsall neglects to say that Smith was one of several polygamous prophets produced by the fervent Christianity of the Second Great Awakening. A New Hampshirite, Jacob Cochran, emerged from evangelical religion to say that he was the Holy Ghost. During the revivals that he led, his followers frequently shed their clothing. He took on many “spiritual wives,” for whom sex with Cochran was literally unification with God.4 Another sexually experimental group was the Vermont Pilgrims, led by the red-bearded Isaac Bullard, who called himself the prophet Elijah. The Pilgrims practiced communal marriage. Yet another prophet, Michael Hull Barton, announced himself as the angel Michael of the Bible and accumulated many spiritual wives.5 An even more famous figure was the colorful Robert Matthews, aka Matthias, who said that Jesus had inhabited his body and that he was now God the Father. He also had a number of wives.6

Then, too, there was the nineteenth-century free-love movement. Pearsall briefly discusses the free-love advocates Mary Gove Nichols and her husband, Thomas Low Nichols. It would have been exciting had she extended her analysis to the sexual practices at nineteenth-century free-love communities such as Modern Times on Long Island, Berlin Heights in Ohio, and Ceresco in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. These communities abolished conventional marriage, which was viewed as a prison for women, and replaced it with an open arrangement in which women and men followed so-called passional (that is, passionate) attraction in choosing sexual partners. At Ohio’s Berlin community, a journalist reported, there was a “Love Cure” building, where people paired up casually. The community issued a free-love screed that announced, “MARRIAGE IS THE SLAVERY OF WOMAN: Free Love is the freedom and equality of woman and Man: Polygamy is Marriage multiplied: FREE LOVE IS MARRIAGE ABOLISHED.”7 Another journalist reported a free-love event in Ohio where a woman said that “altho’ she had one husband in Cleveland, she considered herself married to the whole human race. All men were her husbands, and she had an undying love for them.” She asked, “What business is it to the world whether one man is the father of my children or ten men are?”8

The free-love movement reminds us of the distinctions between the various forms of polygamy that Pearsall covers. Free love was influenced largely by the utopian socialism of the French reformer Charles Fourier, who called for a reorganization of society based on the liberated expression of natural passions. Mormonism sprang from the evangelical zeal of the Great Awakening that energized converts and led some to believe that they were part of the godhead. Complex marriage, the Oneidans’ version of experimental sex, stemmed from perfectionism—the belief that true believers were cleansed of sin and constituted a community of the redeemed in which everything, including sex, was shared. Native American and West African polygamy was an expression of ancient tribal beliefs and practices in the face of colonial power.

Such differences between various forms of polygamy help account for the fragmented quality of Pearsall’s book. She explains at the start that her topic is exceptionally broad and that she proceeds “in a roughly chronological narrative.” Indeed, chronology is about the only structure that Pearsall can follow, given her ambitious aim of covering polygamy in several geographical regions over the course of four centuries.

While this discontinuity makes for a choppy reading experience, it underscores the arbitrariness and relativism of human motives. Spousal abuse, rigid patriarchal domination, and sex between adults and young adolescents—these have been among the behaviors of polygamists who felt justified by their religion or ancient traditions. Pearsall’s wide-ranging study reminds us of Margaret Atwood’s line, “There were lots of gods. Gods always come in handy, they justify almost anything.”9 The Pueblo chief Po’pay felt as comfortable with plural marriage as did Solomon, John Humphrey Noyes, Brigham Young, and, for that matter, Warren Jeffs. For them and other polygamists, God was always there, always leading them to the next wife.

This Issue

April 9, 2020

Bigger Brother

Stuck

In the Time of Monsters

-

1

Venus’ Miscellany (New York), July 11, 1857. ↩

-

2

Pearsall informs us that although sodomy was then a capital crime, only two men were executed for it in seventeenth-century New England. As for adultery, “the standard punishment…was a fine of up to £20 and thirty-nine lashes” (Dorothy A. Mays, Women in Early America: Struggle, Survival, and Freedom in a New World (AB–CLIO, 2004), p. 12.) ↩

-

3

See Free Love in Utopia: John Humphrey Noyes and the Origin of the Oneida Community, compiled by George W. Noyes (University of Illinois Press, 2011), pp. ix and 59. ↩

-

4

Gamaliel B. Smith, Report of the Trial of Jacob Cochrane, on Sundry Charges of Adultery, Lewd and Lascivious Conduct (James K. Remich, 1819), p. 41. On Cochran and the other polygamous prophets discussed in this paragraph, see my book Waking Giant: America in the Age of Jackson (HarperCollins, 2008), chapter 4. ↩

-

5

“A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing,” Boston Recorder, August 15, 1844, p. 132. ↩

-

6

“Memoirs of Matthias the Prophet,” Boston Investigator, May 29, 1835. See also Paul E. Johnson and Sean Wilentz, The Kingdom of Matthias (Oxford University Press, 1994). ↩

-

7

Illinois State Journal, April 24, 1858. ↩

-

8

The Ottawa Free Trader (Ottawa, Illinois), August 8, 1857. ↩

-

9

The Blind Assassin (Nan Talese, 2000), p. 27. ↩