What if the finest, funniest, craziest, sanest, most cheerfully depressing Korean-American novel was also one of the first? To a modern reader, the most dated thing about Younghill Kang’s East Goes West, published by Scribner’s in 1937, is its tired title. (Either that or its subtitle, “The Making of an Oriental Yankee.”) Practically everything else about this brash modernist comic novel still feels electric.

East Goes West has a ghostly history: at times vaguely canonical, yet without discernible influence, it has been out of print for decades at a stretch, and surfaces every quarter-century or so as a sort of literary Brigadoon. (Last year’s Penguin Classics edition is its third major republication.) Kang’s debut, The Grass Roof (1931), captures the twilight of the Korean kingdom in the first two decades of the twentieth century, as Japan colonizes the peninsula. Its narrator, Chungpa Han, is a precocious child whose thirst for education takes him from his secluded home village to Seoul, three hundred miles away; into the heart of Japan; and finally to America, where East Goes West picks up on the pilgrim’s progress.

Though both novels were first published to great acclaim by Maxwell Perkins—the legendary editor of Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Thomas Wolfe—they stand as the alpha and omega of Kang’s fiction career: an explosion of talent, followed by thirty-five years of silence. His sensual, impudent voice and bold escape from his homeland (“I had seen the disintegration of one of the first nations of Earth”) provoked Rebecca West to exclaim, in a review of The Grass Roof, “What a man! What a writer!” Yet by the time of his death in 1972, Kang had faded from public recognition.

The fictional Chungpa Han’s itinerary and timeline generally tracks Kang’s. Born around 1903, he grew up in rural North Korea, stuffing himself with Korean and Chinese poetry. At age eleven, he trekked alone to Seoul, a journey of sixteen days, to further his education, then went to Japan the next year. Back in Korea by 1919, he participated in the March 1 Movement, a nationwide uprising against Japanese rule, for which he and thousands of others were jailed. (Among The Grass Roof’s virtues is a ground-level account of the event and its aftermath.) Following a thwarted attempt to leave Japanese-occupied Korea via Siberia, and a second spell in jail, he finally made it to the US three years before the Immigration Act of 1924 effectively outlawed most immigration from Korea and other East Asian countries until it was replaced in 1965.

His audience in the 1930s, then, was not the Korean diaspora, for the simple reason that there hardly was any. (Between 1903 and 1924, fewer than 10,000 Koreans had come to the US, most of them as laborers in Hawaii and California.) He wrote instead as the last of his breed, addressing those Americans with little sense of Korea’s existence, let alone its vexed status as a colony of Japan (1910–1945). He was a man without a country: an alien unable to obtain US citizenship due to immigration restrictions, and unwilling to return to a land that no longer existed.1

He assimilated with a passion. He studied at various schools (obtaining a master’s in English education from Harvard) and married a Caucasian woman, a Wellesley graduate named Frances Keely (she was also an alien for a time: her US citizenship was revoked for marrying an Oriental). His deep knowledge of East Asian culture equipped him to be a writer for the Encyclopaedia Britannica and a curator for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1929 he taught literature at New York University, living in Greenwich Village. At NYU, Kang befriended fellow instructor Thomas Wolfe, on the verge of publishing Look Homeward, Angel. Wolfe changed Kang’s life by recommending him to Perkins, who brought out The Grass Roof—the only book that Wolfe ever reviewed.

By the time immigration restrictions loosened in the 1960s, Kang’s writing from the 1930s must have seemed remote to newer arrivals. The next significant novel in English by a Korean immigrant, Richard E. Kim’s The Martyred (1964), was its stylistic antithesis: a brooding, Camusian work set during the Korean War (1950–1953), in which Kim served as an infantry lieutenant.2 Kang’s DNA is hard to locate in the varied work of the Korean-American novelists since. As a result, East Goes West’s tumbling prose and loose, picaresque structure feel amazingly “free and vigorous” (per Wolfe) today.

Early on, East Goes West appears to be a comedy of errors, perhaps laying the groundwork for a Horatio Alger story: youthful Chungpa Han arrives alone in New York City from Korea, via Japan and Canada, with two letters of introduction, four dollars, and the keen sense of life starting anew. (Chungpa notes that the Korean word for “boat” is the same as that for “womb.”) He extols Manhattan as “that magic city on rock yet ungrounded, nervous, flowing, million-hued,” crammed with “young, slim, stately things a thousand houses high,” a “great nature severed city [festooned] with diamonds of frozen electrical phenomena” that is destined to be “the vast mechanical incubator of me.” The description practically bursts into flames; here and elsewhere, Kang calls to mind no one so much as that later Wolfean disciple, Jack Kerouac.3

Advertisement

The very sight of New York stirs his soul because—more than Paris, London, or “age-buried Rome”—it’s the apotheosis of the Machine Age, and thus the opposite of his homeland, whose resistance to change spelled its doom. Whereas in The Grass Roof Chungpa depicts his native country as a wonderland of faithful canines and revered crazy poets, easily crushed by a more modernized Japan, on the second page of East Goes West, he describes Korea in darkly apocalyptic terms, a catastrophe out of science fiction:

It was my destiny to see the disjointing of a world. Upon my planet in lost time, the heyday of life passed by. Gently at first. Its attraction of gravity, the grip on its creatures maintained through its fervid bowels, its harmonious motion weakened. Then the air grew thin, cooler and cooler. At last, what had been good breathing to the old was only strangling pandemonium to the newer generations.

Fleeing “the death of an ancient planet,” our hero lands in an America so strange it might as well be Mars. He announces that the book which follows—East Goes West—will be “the record of my early search” for roots in this foreign place.

Reaching New York, Chungpa Han is in high spirits. For his first night, he splurges on a mid-tier hotel. The elevator gives him a “funny cool ziffy feeling,” and the bathroom is a marvel, unlike anything in Korea. The hotel mirror is also a novelty; in his old life, a mirror was generally a covered thing “about the size of a watch.” Seeing his old-world face in a brand-new country brings on something close to hypnosis:

I have read that Koreans are a mysterious race, from the anthropologist’s viewpoint. Mixtures of several blood streams must have taken place prehistorically. Many Koreans have brown hair, not black—mine was black, so black as to have a blackberry’s shine. Many have naturally wavy hair. Mine was quite straight, as straight as pine-needles. Koreans, especially women and young men, are often ivory and rose. My face, after the sun of the long Pacific voyage, suggested copper and brass. My undertones of the skin, too, mouth and cheek, were not at all rosy, but more plum. I was a brunette Korean. Koreans are more animated and hot-tempered than the Chinese, more robust and solid than the Japanese, and I showed these racial traits as well…. My limbs retained a look of extreme plasticity, as in a growing boy, or in a Gauguin painting, but with many Koreans, even grown up, they still do.

For Chungpa to establish his alien self at the outset of this story, describing it as a specifically Korean body, distinct from the somewhat better-known Chinese or Japanese ones (and even from those of other Koreans), is a radical move. It suggests that American readers need to know exactly how he looks, or they’ll fail to understand his story. There’s also a quality of self-revelation, as though he needed to go halfway around the world to see himself fully, in the privacy of a New York hotel room. Rather than dwelling on the melancholy of anatomy, he notes his “extreme plasticity,” to show that he’s ready for America to transform him.

On his second day in New York, Chungpa Han gets a haircut, not grasping that shampoo, shave, and other services cost extra. He leaves the barbershop with a dime to his name. He is counting on imminent employment, but his two letters prove useless. A nickel gets him a space on a basement floor, in what he likens to “a crypt of roughly piled bodies.” In just forty-eight hours, he’s gone from Whitmanesque paeans to a premonition of death. The feeling of liberation from his old life has been replaced by the need to adapt. Constant reinvention, he learns, is in the American grain.

So too does the book reinvent itself. A rags-to-riches arc dissolves into a journey through eastern North America. Already steeped in the English poetic tradition, Chungpa pursues his “avid desire for Western knowledge” while he works a succession of jobs. Educational opportunities, finances, and pure wanderlust compel him to roam, and the scene shifts from New York (a humiliating stint as a houseboy, assistant to a tea importer, waiter at a Chinese restaurant) to Nova Scotia and other spots in Canada (college, box factory, farming), then Boston (pen salesman, more school, book salesman, busboy), Philadelphia (department store), and myriad unnamed points across the country, eventually returning to Manhattan.

Advertisement

Even as a boy, Chungpa wandered, as chronicled in The Grass Roof. At the age of eleven, determined to be a “big man,” he “wanted to go to Seoul one day and get this country straightened out.” (“I will drive out all those Japanese.”) In Seoul at last, after a grueling solo journey, he writes home: “I am not going to send any more letters until I get more education. There are no good schools in Seoul.” The grit offsets his grating precocity: seemingly from birth, Chungpa is fluent in classical Chinese poetry, a hallmark of the Korean literati. He quotes it at the drop of a hat, and revels in his destiny as a future pak-sa, a gentleman scholar.

The looming destruction of his country by its colonizers ultimately renders Chungpa heroic, a young man whose resourcefulness outshines his arrogance. What he held as his birthright gets dashed against political reality:

For the first time in my life I could not make up my mind. After graduation, what? Get a job. Yes, but in Korea I should have to be a subordinate of a Japanese, always I would get one-tenth of that which a Japanese with the same degree would get, I could never become a pak-sa for there were no more pak-sas and a Korean premier did not exist…. If I went back to Korea, and returned to become a villager for always, was that any fun? Why should I keep on to manufacture babies for which there could be no future? I saw what Japan’s policy toward Korea would be: all who could not be assimilated would be slaughtered…and driven away.

He finally secures passage (and eludes Japanese officials) by accompanying a widowed American missionary and his four children, impersonating an “ignorant coolie boy.”

As a narrator, however, Chungpa is more charismatic in East Goes West. When it dawns on him that America is like nothing he could have imagined, the comedy kicks in. Reviewers took The Grass Roof for straight autobiography, and East Goes West saw the same fate. Kang’s second book, however, shows him to be a skilled novelist rather than a simple recorder of his own life. Kang turns down the volume on his narrator whenever Chungpa encounters someone who captures his curiosity or affection. The novel overflows with memorable motormouths, busybodies, sad sacks, and dreamers, both foreign and domestic, white and black and “Oriental.” (“I was outside the two sharp worlds of color in the American environment,” Chungpa notes, allowing him to observe his new countrymen with an unbiased eye.)

The first bit of fun arrives in the form of George Jum, a fellow expat with whom Chungpa has corresponded. Originally a diplomat, George now works as a cook and leads a happy bachelor life on West 72nd Street, where he invites his countryman to stay. His debonair style and instant friendliness win over Chungpa (and the reader—you can’t help but smile when his name pops up). Like P.G. Wodehouse’s Bingo Little, he’s in love with being in love, rhapsodizing on the nature of American romance. While George irons pants to prepare for his day, Chungpa asks whether he’d ever get hitched. “I am thinking of love, not of marriage,” George begins, then expounds uninterrupted for a page, gleefully mixing truisms (“Anything that law commands in the form of thou shalt not, that thing man wants more”) with boneheaded logic: “But then civilization is a good thing. We enjoy motor cars and bathtubs. And who would not enjoy having more than one wife?”

George Jum functions as the happy opposite of the older, highly cultured To Wan Kim, some sixteen years removed from his homeland, who can neither find peace in the West nor consider himself a Korean: “I have been away so long I do not feel one any longer,” he confesses. Chungpa glimpses the refined and rootless gentleman during his first stay in New York, though they don’t introduce themselves until a few years later, recognizing each other at a Chinatown restaurant.4 The doomed To Wan falls in love with Helen Hancock, a Boston blue-blood whose older cousin fancies himself a connoisseur of all things Asian, yet whose family sternly forbids their romance. George Jum and To Wan Kim loop through Chungpa’s life at irregular intervals, suggesting possible paths for the educated Korean immigrant—or the necessity of creating your own.

To Wan has a tragic trajectory, but George shines as the first of dozens of amusing secondary portraits. Others include his fellow Korean Doctor Ok, who has racked up four degrees and counting (perhaps a jab at Syngman Rhee, future first president of South Korea, who rather incredibly obtained, between 1907 and 1910, a BA from George Washington, an MA from Harvard, and a Ph.D. from Princeton); the irrepressible D.J. Lively, who runs a pyramid scheme selling a self-help tome called Universal Education; and Senator Kirby, who picks up a hitchhiking Chungpa and heartily tells him to call himself an American—and also that Marlowe wrote Shakespeare’s plays.

But there’s another strain of humor here, a sort of deadpan ramble, anticipating the later comic novels of Charles Portis, which draw laughs by cutting off a seemingly limitless series of observations at an unexpected point. In this vein, Kang produces witty portraits of Chungpa’s fellow foreign college students, such as an Italian roommate who somehow removes and dons his necktie only when no one’s looking, and the homesick Peking University graduate Eugene Chung, whose sober hobby is his new typewriter:

When he was not writing long letters to his wife in Chinese, he was practising [sic] with his typewriter the touch method, spending hours and hours on just his name…. His only regret was, he could not combine his two interests, write his wife and at the same time use that machine. This he could not do because she knew no English.

Kang is even funnier when observing whites. During his Canadian sojourn, Chungpa is unaccountably fascinated by a mildly unusual ménage:

I remember the Stratford [Ontario] barber who boarded at Mrs. Moody’s all the time…. This barber looked like a farmer and not a barber, and in fact I think he had newly become a barber, not liking the dirt of farm life. It was his ambition to get down to Boston. He was engaged to a girl who ran the only beauty shop in Stratford and who was always unusually dressed. Her clothes, though they were made at home by her dressmaker sister, seemed copies of Parisian styles. One time she would appear in a dress with long sleeves—extraordinarily long, I mean, down to the knees. Or she would wear an enormously wide flopping straw hat with streamers. Besides, she was always exceptionally decorated underneath, whether as an advertisement of her shop or just to take advantage of it, I can’t say…. She, too, no doubt, was eager to get down to Boston. They never managed it. Several years later, as I drifted north once more, I saw them both in Stratford, married and settled down…. They had a fat boy-baby now, whose ambition ultimately perhaps will be to go to Boston.

The thwarted, multigenerational ambition to make it to Boston is the chief joke here, but it’s kept alive by little virtuosic touches: the barber’s farming past, the shopkeeper’s outré clothes, the interjections (“I mean,” “I can’t say”) that remind you that the man watching the comedy play out—Chungpa Han—must look like no one else they’d ever seen. “I was inexorably unfamiliar,” he reflects.

The novelist and memoirist Alexander Chee’s rousing introduction to the new Penguin Classics edition of East Goes West argues strongly for its relevance today. Chee says that “Kang wrote East Goes West as a call to action, a call for [America] to live up to the dream it has of itself,” and he rightly touches on how Kang illuminates a whole shadow community of marginalized immigrants—most of them Asian, all in a sort of historical limbo. Some thrive, most stagnate, a few go mad with homesickness. “Perkins tried to get Kang to write a happier book,” Chee points out, “but Kang had deliberately imagined a less successful and happy life for Han than the one he himself had lived, in part to dramatize the plight of those less fortunate than he was.”

But I’m more cynical than Chee about the book’s utility as a rallying cry. Its value is in the heady mix of high and low, the antic yet clear-eyed take on race relations, the parade of tragic and comic bit players, and above all, the unleashed chattering of Chungpa’s distinctive voice. Underlying the richness and humor, there’s a deep pessimism about making it in America, for anyone not white and male. In Boston, a college-educated black friend, Wagstaff, works as an elevator man, and “expected all his life to be an elevator man.” Chungpa’s white male coworkers at the Boshnack Brothers department store in Philadelphia spread rumors that their female counterparts, who earned $12 a week, “made a side-living by prostitution, since it was impossible to live on that in a big city.” (In the company’s men’s club, they throw around the n-word with sickening impunity.)

As for Chungpa, his jobs have all been menial; how is his American existence any better than life under the Japanese back home, who “wanted all honored men in Korea to become coolies”? “I couldn’t make him understand about Korea,” Chungpa says of a bum; by the end of the book, white America by and large still doesn’t know what to make of him.5

Catching the flu in Boston, Chungpa has a vision of despair. “Nobody would know the moment when I died and nobody would care,” he moans. “Many Oriental students had died like this on foreign soil.” A fellow expat’s death merits a brief mention in the paper on “the suicide of a friendless ‘Japanese’ on Bleecker Street.” Even in death, Koreans remain indistinct.

Chee and I could both be right. East Goes West is bookended by dreams, the first an enthralling fantasy of New York, the last a soul-killing nightmare: a final verdict might depend on how you interpret the latter. At some point in his American life, a slumbering Chungpa is vouchsafed a glimpse of long-lost boyhood friends (previously unmentioned in East Goes West, but present in The Grass Roof) before plunging into “a dark and cryptlike cellar” somewhere “under the pavements of a vast city”—flashing back to his destitute second night in New York. A “red-faced” mob shoves its torches “crackling, through the gratings” of the cell that he shares with “some frightened-looking Negroes.”

Chungpa’s own interpretation of this incendiary scene feels tacked on, homiletic. To be killed by fire in a dream “augurs good fortune,” according to “Oriental interpretation.” He gives it a Buddhist spin (death symbolizes “growth and rebirth and a happier reincarnation”) that feels peculiarly unconvincing—the only line in the book I don’t believe he means. The book ends abruptly, as though the chatty Chungpa is still too rattled by what he’s conjured.

After World War II, in that heartbreakingly brief span of time between the liberation of Korea from Japan and the outbreak of the Korean War, Kang returned to his homeland for two years, at the invitation of the US Army Military Government in Korea (going by the mystical acronym USAMGIK). He had been away too long; his presence didn’t make sense to Koreans or to himself. “Thirty million frustrated, confused, and humiliated Koreans are trying to become a nation,” he complained to Perkins. “We are getting nowhere.” In Robert T. Oliver’s hagiographic Syngman Rhee: The Man Behind the Myth (1954), Kang is depicted as ineffective and apolitical, telling reporters: “I don’t like or trust Dr. Rhee…I’m a writer, an artist.” According to Oliver (who was, in essence, Rhee’s stateside publicist during this time), Kang’s irrelevance to Koreans led US officials to shunt him to a back room.

In 1948 Younghill Kang returned to the US, and during the Korean War, according to Sunyoung Lee’s chronology, “Kang’s restless anxiety [over the war] makes it difficult for him to reacculturate to American life.” In his 1954 application for a Guggenheim fellowship, he writes in anguish:

It is natural for me to love America and fight for her, it is natural for me to love Korea…. I know why the UN or [President] Truman has done what has been done [i.e., entered the war upon Communist North Korea’s invasion of the South]. But I also know we have spent millions and lives and created enemies in Korea…. What is it they fight? Communism? democracy?… To the average Korean what do they mean? The typical Korean is a hunted uneducated farmer. One thing makes him go mad, that 38th Parallel, separating parent from child, husband from wife…. Whichever force won this war from without shall lose it politically. The operation was a success, but the patient died—it’s that kind of success.

The great powers—the US on one side, China and the Soviet Union on the other—were spelling out the terms of Korea’s doom, just as surely as Japan had earlier in the century.

With Frances, he translated Meditations of the Lover, poems by the Korean poet and Buddhist monk Han Yong-un (1879–1944); it was rejected by Scribner’s. (Perhaps Han’s surname inspired Chungpa’s.) Save for a 1954 translation of the Japanese play Anatahan (Hermitage House), Kang never published another book in America. Through the 1950s, he wrote for various encyclopedias, mostly entries about China. When he wasn’t teaching or working on farms on Long Island, he drove around the country delivering lectures on topics like “The Democratic Opportunity in Asia.”

By chance, two strange sheets of paper fell out of my used copy of The Grass Roof (a 1966 printing of the 1959 Follett reissue), and they afford a rare peek at the nature of Kang’s later life, long after the dissipation of his fame. The book was inscribed by Kang to a reader in 1970, two years before Kang’s death. The sheets, a pair of advertisements for himself, were almost certainly made by Kang; though undated, they might be the last thing he wrote for some imagined general reader.

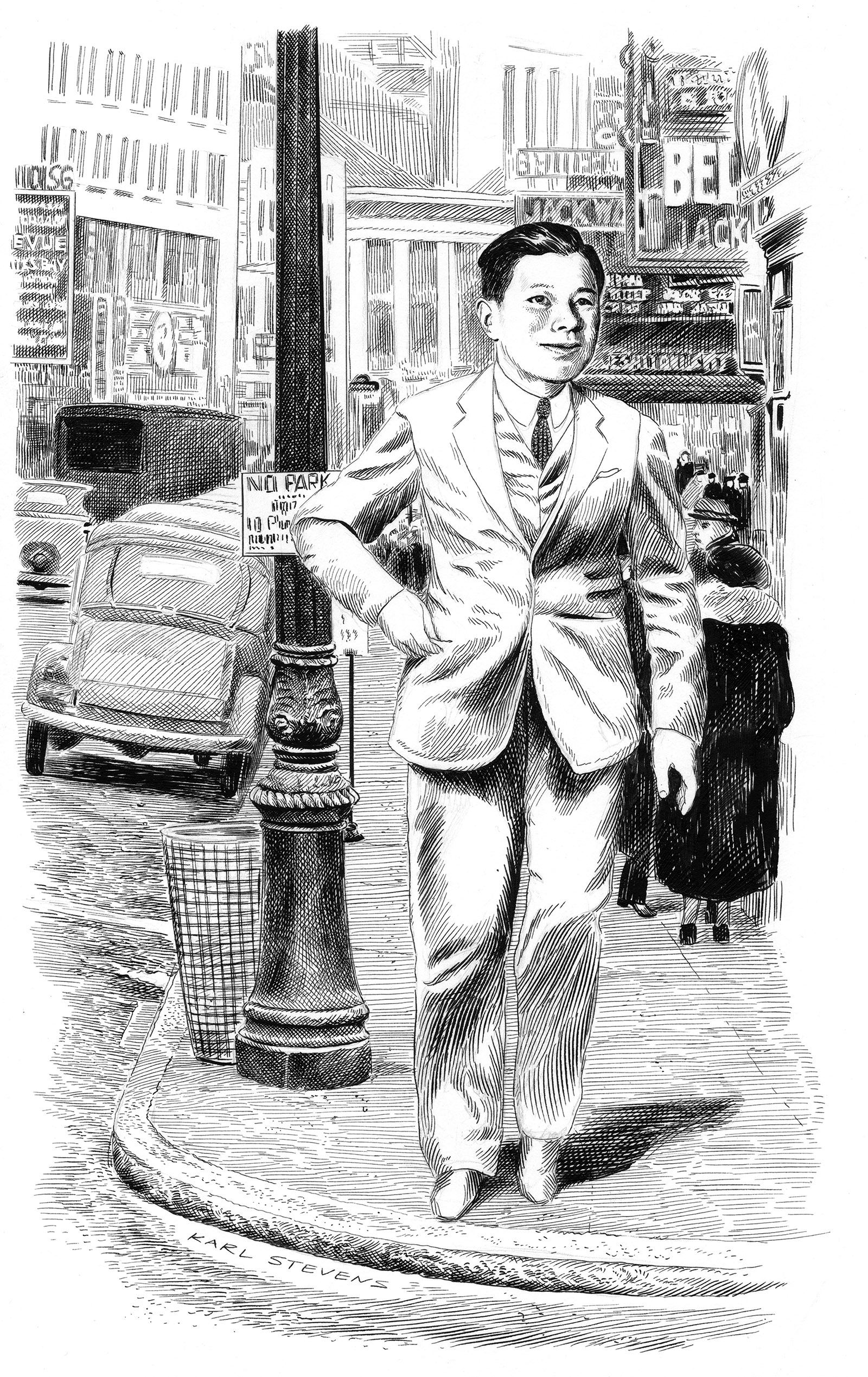

Sheet one, which I take as being of earlier origin, is the more professional looking. It has a portrait of Kang in coat and tie, seated at a desk, downcast eyes studying an open book. Plaudits include what appears to be a long blurb from Pearl S. Buck. But only the first few words (“one of the most brilliant minds of the East”) are hers; the rest is a Who’s Who–like list of accomplishments. The reverse displays nine raves for his novels. The layout is dense but orderly, and the spotlight is firmly on his rich literary legacy.

The second sheet appears to be from a later date. Ostensibly it touts his public-speaking bona fides. One side bears typewritten extracts from his speeches, plus his home address in Huntington, Long Island. The other side, though, looks like the snapshot of a meltdown: a blizzard of text, in a dozen conflicting typefaces and angles, comprising shards of testimonials and invitations (“LUNCHEON IN ALEXANDER DINING HALL”). It’s hard to know what’s being offered. The word “Vietnam” ominously appears, unattached; then the eye makes out the tiny words “Or Negotiation?” A chunk of Rebecca West’s age-old review drifts through, as does a Grass Roof review, but it’s clear he’s long since abandoned his life as a novelist.

It’s a shocking composition. The ennobling lecture extracts on the obverse (“Great books are still the greatest weapons in fighting, and the only lasting psychological propaganda”) have been replaced by noise and chaos. No novelist’s permanence is assured, but given Younghill Kang’s primacy as the first Korean-American novelist, this feels like a higher order of defeat, as though the country that he so endeavored to be part of had turned its back on him. To gaze upon this frenzied collage is to wonder if some part of his soul had taken up residence in the cell of his youthful alter-ego’s hair-raising dream—a form of PTSD, from a war he wasn’t actually in but that he felt in his bones.

The Penguin edition of East Goes West reminds us of how excellent he really was. Written in the 1930s, set in the 1920s, the book is thrillingly timeless. Kang’s obscurity cannot negate his heroic path to becoming a great American novelist—casting off one tongue to master another. In a 2008 essay in Guernica on Korean-American fiction, Chee aptly calls East Goes West a “Nabakovian [sic] tour de force.” Though Nabokov expressed no interest in “the entire Orient,” he and Kang—poets in their youth—have much in common. Both lived from the turn of the century to the 1970s, and in their late teens fled homelands in upheaval. Both found fame in the US, as stylistically daring novelists for whom English was a second language—in Kang’s case, third or even fourth, as he wrote poetry in Chinese and studied in Japan.

Given that The Grass Roof and East Goes West precede Nabokov’s American debut, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (1940), by nine and three years, respectively, it’s worth asking: Was Kang the first exophonic American to execute such highwire English prose? Regardless of whether he’s the right answer to this parlor game, Kang wrote a vast, unruly masterpiece that is our earliest portrait of the artist as a young Korean-American, at a time when hardly any Americans had heard of, let alone seen, a Korean. His insistence on the value of his own identity to a modern world that had essentially condoned the foreign takeover of a sovereign nation brings to mind West’s tribute: What a writer—what a man.

This Issue

April 23, 2020

Resistance Is Futile

The Brilliant Plodder

-

1

In 1939 the Committee on Citizenship for Younghill Kang and Illinois representative Kent E. Keller introduced a bill (H.R. 7127) for his naturalization, garnering support from Perkins, Charles Scribner, Pearl S. Buck, Malcolm Cowley, and others. The bill was rejected. ↩

-

2

Kim came to the US after the war in 1955, eventually studying at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where his teachers and admirers included Philip Roth. ↩

-

3

Even in a more restrained register, New York brings out Kang’s lyricism: “Outside the restaurant a heavy rain like black ink was pouring. Like beetles called up by the rain, the shiny taxis twisted and turned cumbrously, seemed bound to collide in their narrow quarters.” ↩

-

4

Explaining and complaining about Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, his new home, he says, “but village…cozy name, ne?”—surely the first rendering of that Korean word—yes—in American fiction. ↩

-

5

When he tells the friendly Senator Kirby, “But an Oriental has a hard time in America,” Kirby replies, “There shouldn’t be any buts about it! Believe in America with all your heart…. You should be one of us.” Chungpa informs him, “But legally I am denied.” ↩