On the last page of Horace Pippin, American Modern, Anne Monahan reproduces a witty and informative drawing titled How to Look at Modern Art in America. Created by Ad Reinhardt and published in PM Magazine in June 1946, it delineates the art scene of the day in the form of a big tree, with its soil, roots, main trunk, big boughs, branches, and, ultimately, individual leaves all labeled with names. The chief point of the drawing is the way the big bough on the right, loaded with names of representational artists, including Marsden Hartley, Ben Shahn, and Georgia O’Keeffe, is about to crash off the tree, while the other big bough, full of the names of abstract artists, including Willem de Kooning, Josef Albers, and Mark Rothko, is alive and well. (Reinhardt was an abstractionist.) Sitting here and there on the great tree are a handful of birds, each named for a presumably independent art world figure. Only one bird, in a drawing that contains some 150 names, is flying through the sky. This is Horace Pippin. He is heading toward the tree’s left, or living, side.

In many ways, Pippin, who died at age fifty-eight the month after the drawing was published, is in the same special and isolated position today. A self-taught artist who began painting when he was around forty, and whose generally small-size pictures include portraits, still lifes, and family scenes, he has long made viewers uncertain about the difference between being a self-taught, folk or naive, artist and a trained one. His rendering of facial expressions, human anatomy, or the interior space of a scene can be awkward, even crude. He is on wobbly ground with the relative proportions of a club chair and a vase of flowers, or with how to get a chair that was meant to face forward to do so. Yet he was a gifted formal artist with an enviable feeling for color. More than that, he had an avid interest in the way other painters worked and a need to make his own versions of the kinds of pictures he responded to.

In Horace Pippin, American Modern, Monahan takes up the very issue of how we are to think about the artist now, and fortuitously the Philadelphia Museum of Art has on long-term view a wonderful exhibition entitled “Horace Pippin: From War to Peace,” which brings together the museum’s small but choice collection of his work. How powerful Pippin can be is on full display in The Getaway (circa 1938–1939), though the artist’s assurance may be hidden at first by his inauspicious subject. We might not expect to be admiring the construction of a picture showing a fox with a bird in its mouth, running through the snow on a moonlit night. But the sheer balance of elements in The Getaway, and how this balance is achieved through color, are remarkable.

Essentially, the painting has three colors, which fold back and forth on one another. The picture’s top half is black (for sky), broken up with white-gray clouds. The bottom half is white (for snow), broken up with a grayish-black road and some little buildings. The fox is fox-colored, and far away in the black top of the scene there are touches of this same color in more little buildings. The top and bottom halves of The Getaway are thus ingenious near mirrors of each other. It is almost as if we were looking at a demonstration of a math formula. Yet the structural elegance of the painting does not detract from its evocation of a furtive and graceful animal in action on a glistening winter night.

Perhaps Reinhardt was right in showing Pippin moving toward being an abstract artist. But did he give Pippin his elevated position in the art world of the time only because of his artistry? Museumgoers today might be surprised by Pippin’s renown in the first half of the 1940s. He was a nationally and even internationally known artist, in part for biographical reasons. He had sustained a severe wound to his right shoulder fighting in World War I. He was right-handed, and to paint at all, at least in the beginning, he needed to use his left hand to guide the not very movable right one, which held the invariably small brushes. That he was African-American and supported his wife and stepson as a handyman before his art took off were crucial elements in what might have made him a story even if he had been less of an artist.

It undoubtedly also helped that Pippin came from a part of the world that was geared to appreciating his gifts. Based in the small city of West Chester, Pennsylvania, an hour or so west of Philadelphia, he lived in proximity to, among others, the well-known illustrator N.C. Wyeth and the collector Albert Barnes, both of whom admired his painting and wanted people to know about it. In a short time Pippin had gallery representation in Philadelphia and New York, with each of his dealers eyeing the other warily, for good reason. He was given shows in both cities and in 1942 at the San Francisco Museum of Art, and a list of Hollywood luminaries waited for available pictures. There were serious reviews in The New York Times and The New Yorker, coverage in the art press and news magazines, and—a detail that gives a real taste of Pippin’s stature—he, Salvador Dalí, and Fernand Léger each had separate shows at the same time in 1941 at the Arts Club of Chicago.

Advertisement

The 1930s and 1940s were years when other self-taught artists were achieving national renown, in part because—as Lynne Cooke made clear in the catalog of her 2018 exhibition “Outliers and American Vanguard Art”—curators at the Museum of Modern Art believed that such work was part of the larger story of contemporary developments. Pippin, though, stood apart from other self-taught—or as they were called in a 1938 show at the Modern, “popular”—artists. He didn’t have a sense of the world, or a vision, that he wanted to keep coming back to.

He was quite unlike self-taught contemporaries such as Morris Hirshfield, with his repeated images of women and animals that emphasized echoing, curvilinear shapes, or Anna Mary Robertson Moses, known as Grandma Moses, who kept returning to distant views of a busy, domestic, rural idyll. A third such artist of the time, John Kane, roamed a little in his choice of subjects, but whether he was showing himself as an artist or sites and people in Pittsburgh, where he lived, his paintings, which often had a slightly fuzzy, softly focused appearance, were seemingly about his daily life. Pippin, though, operated more like his nighttime marauder in the snow. He never lost the desire to take up a new theme, usually exploring it in a few examples (and sometimes coming back to it) before turning to another.

He began with scenes about his experiences as a soldier, and went on, though not directly, to paint portraits of people he knew or, in the case of Marian Anderson, admired. He had a phase of making still lifes of flowers in vases, and, in a related group, pictures of living rooms with chairs and knickknacks on tables and mantelpieces. There were paintings with religious themes. The strongest, Christ (circa 1935–1939), a close-up of Jesus looking both pensive and dolorous, was owned by the writer Alain Locke and left to Howard University. Taking off from Edward Hicks’s paintings of the Peaceable Kingdom, Pippin made a few versions of that scene, which shows an accord between wild and tame beasts and is based on a passage in Isaiah.

Some of Pippin’s best-known works, then and now, are family scenes, usually set in hardscrabble kitchens and presenting a mother tending her children (and rarely accompanied by a grown man). Often showing women smoking pipes, or little boys in what might be their Sunday best, or bits of exposed wall where the plaster has fallen off, the paintings present a slice of African-American life in what viewers can believe are documentary terms.

There are sweet aspects to these pictures, particularly the soft, shadowy light around the stoves and the spots of brightness provided by the hooked rugs. But in general they are not very exciting Pippins. There is an uncenteredness to the compositions and a folk art–like stiffness to the way many of the details have been drawn. This is the case as well with a number of the oils in a series concerning John Brown and in another devoted to Abraham Lincoln. In Pippin’s hands, the faces of these historic figures feel almost hacked out. Yet in another group of his pictures—scenes whose subjects are men traveling or involved in sporting activities—he brilliantly knits together even the smallest elements into one unified fabric.

In paintings such as the 1933 Buffalo Hunt and The Country Doctor (circa 1935–1939), it is the dead of winter, with wind and snow everywhere. Everything we see has been rendered in black, white, and gray, and perhaps even more than The Getaway these pictures are gorgeous, even voluptuous, demonstrations of Pippin’s skill in rendering full worlds in these few colors. He does this again in his Christ, and he employs generous amounts of pure, unmixed black, or white, or both, in numerous works. It is puzzling that his affinity for these headstrong colors has apparently gone unnoted. But then Pippin did not use them all the time, and his success did not depend on them. A viewer simply becomes aware of this aspect of his art after a while and looks forward to how he might use these colors on another occasion.

Advertisement

Anne Monahan has been writing about the artist since the early 1990s, and at this point she is undoubtedly more aware of the minute ins and outs of his life than any commentator. She says, for example, that if Pippin did not get a specific painting to a show as promised in 1941, the reason might have been because he needed to work on it outdoors, and her sleuthing has revealed that during the period in March when he would have been going to the site, “West Chester’s average temperature…was thirty-three degrees Fahrenheit.”

Her book, though, is not a biography. Focusing rather on certain aspects of Pippin’s work—on how he derived some of his images, on the meanings of his handful of pictures showing cotton fields, and on the way he often made gifts of his artworks to well-connected patrons—she attempts to remove what she calls the “homespun” from our sense of the artist. Although she doesn’t refer to him, she takes aim at the thought expressed by the late David Driskell—a painter and for many years a leading voice on African-American art—when he wrote that with Pippin we look at “art from the hand of a gentle soul.” Questioning this kind of assessment, Monahan’s study is of a piece with a number of recent and forthcoming books that aim to show self-taught (or outsider) artists as more in control of their endeavors than previously thought. She could easily be grouped with other historians whose effort now, as George Scialabba puts it in an article entitled “Affirming America” in the Winter 2020 Raritan, is to “make oppressed people out to be subjects as well as victims.”

Monahan “seeks,” she writes, “to destabilize an art-historical caste system that has often consigned autodidacts, especially those of color, to treatments that do not fully reckon with the substance of their work.” To do so, she has drawn on “perspectives from the fields of critical race studies, literary criticism, media studies, history, anthropology, sociology, and technical art history.” By “technical art history” she means reports by conservators that indicate the alterations a creator made in the course of finishing a piece. Monahan finds this important because tracking any decisions Pippin made as he fashioned a picture helps us see that he was as aware of his options as any mainstream artist.

In Monahan’s list of “perspectives,” there is no art history. There is little art in her book, either. She refers to the Surrealists because, as with some of their pictures, there could be odd shifts in the sizes of things in Pippin’s images. But she does not look at him in relation to straight representational painting, which was what he did and what meant the most to him. Nor does she bring into the conversation the way other “homespun” artists worked, though a number of them were rather like Pippin in using various sources and altering them as they went along.

When Monahan looks at Pippin’s paintings, she is most engaged with works that lend themselves to political or moral descriptions. She spends considerable time analyzing pictures such as Cabin in the Cotton (circa 1931–1937) and a group of related (and similar) works from the 1940s. They are historical scenes in which young or old African-Americans appear by fields. For Monahan, they are paintings in which Pippin was offering a “critique” of the cotton industry and a “eulogy” for those who were brutalized by it.

Yet Pippin did not say this, and I am not sure how much of it will be inferred by viewers. What his thoughts were on being black in the America of his time—when, to take merely his city, schools and American Legion posts were segregated—cannot be stated as precisely and emphatically as Monahan would have it. There is no question that he was aware of himself as a black man in a white society and art world. He could describe his painting to a friend by saying, “I don’t do what these white guys do. I don’t go around here making up a whole lot of stuff. I paint it exactly the way it is.”

His pride in the achievements of African-Americans was hardly camouflaged. Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson both received artworks from him. His series of pictures about Lincoln and John Brown were thought to attest to the special place African-Americans gave these men, and in his powerful 1942 painting John Brown Going to His Hanging, the one person in the crowd who seems to register anger and disapproval is a scowling black woman. The Whipping (1941), another historical scene, shows, indistinctly, a black man under the lash of a white man.

It would be strange if there were no such connections in his life and work. Yet they do not sum up his work, which goes in many additional directions, or who he was as a person. But then he is not a flesh-and-blood person in Monahan’s book. He is more like an idea. When he makes pictures having anything to do with the cotton industry, he is a covert activist. When he makes gifts of his pictures to white patrons, he is demonstrating that he is his own man as he navigates through society, though we are not to find him at the same time, she states, a “careerist.”

Monahan deliberately puts a damper on what she calls Pippin’s “personality.” She is certainly right to believe that biographical details can lend themselves to a sense of him as an innocent charmer rather than a “subject.” She goes overboard, though, in maintaining that the Pippin we have heard about from people who knew him, whether black or white, adds up to little. Yes, she says, he was “genial, quiet, funny, serious, dignified, naïve, thoughtful, frugal, spendthrift, a heavy drinker,” but after all, she goes on, he “may have been ‘code switching’ for diverse audiences.”

The Pippin one encounters in stories and anecdotes, however, and in his notes about his days in France in 1918, does not come across as an emotional chameleon. He is, on the contrary, a more grounded and convincing version of the canny pro that Monahan tries to create. Romare Bearden wrote that the one time he met Pippin he was struck most by how “self-possessed” he was, and this is the note that colors Pippin’s level-headed if brief descriptions of his wartime experiences. Self-assurance is what we hear in the anecdotes about him—as when, talking with his friend Edward Loper, who was black and a painter, he remarked, “Ed, you know why I’m great?” and proceeded to tell him. Or when, looking at Matisse’s palette at the Barnes Foundation, he said, according to Selden Rodman, his first biographer, “That man puts the red in the wrong place.” Fearlessness certainly lies behind the way he was continually stretching himself.

He rarely stretched more than in his portrait of Christian Brinton, who was a writer about art and a collector—and the person who probably did the most, in the late 1930s, to get Pippin exhibited properly. The riveting Portrait of Dr. Christian Brinton, an image of a dapper and almost disturbingly intense man in a dark suit, his arms crossed before his chest and his small eyes practically judging us, is a highlight of the Philadelphia exhibition. In its delicacy, it is somehow more like a classic early modern European than American work. Every element in the small picture—the bookcase behind Brinton with its spots of strong color for different spines; Brinton’s flashy tie and matching pocket handkerchief; the different decorative patterns in the large window behind him; the arctic white of his eyebrows and hair—feels self-contained and painted with equal emphasis, as if the picture had been made by a jeweler working with enamel.

Brinton was indirectly responsible for another high point in Pippin’s work: four related paintings that also ask to be judged in the larger sphere of art. Brinton came from a Quaker family that in the seventeenth century helped found a Friends meeting site in Birmingham, not far from West Chester. The site was celebrating its 250th birthday around the time of Brinton’s portrait, and Pippin, in 1940 and 1941, made four subtly different paintings of the meetinghouse. They are daytime pictures, but the long, low, gray stone building is seen through dark tree trunks and leaves, which create a nearly nighttime world.

The central character of the pictures, one might say, is the color white. The building’s many doors, their little triangular overhangs, and the mostly closed shutters are all pure white, and especially if the four works could be seen together—they are in four separate collections, with none unfortunately in the Philadelphia show—the effect of these many different white shapes pushing out through the dark trees would be musical and almost overwhelming.

One wishes they could be seen, too, alongside George Ault’s four nighttime views of a little junction near Woodstock, New York, called Russell’s Corners, which Ault presents with not a soul about and only one light shining. They were made a few years after the Birmingham scenes, in a more taut, polished style than Pippin’s—Ault was a trained, mainstream artist, though never as well known as Pippin—yet both sets of paintings suggest the romantic thought that there is a place that is part of the public world but speaks to you alone.

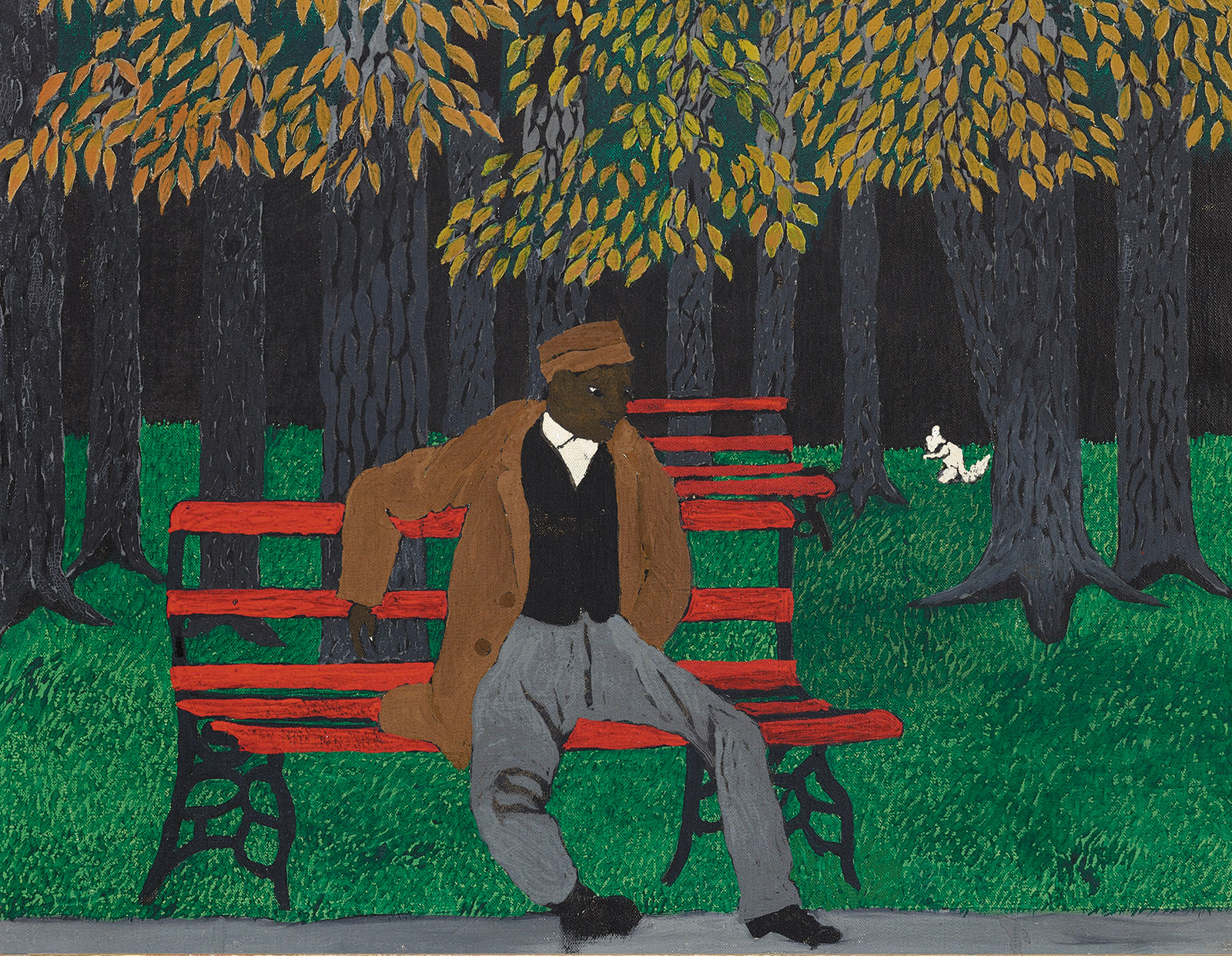

Being alone is perhaps the theme of The Park Bench, a strong small work that completes the Philadelphia show—completes it in the sense that it was among a number of works found in Pippin’s home after he died. It shows a man seated on a red bench in a dark green park, with only a squirrel nearby. Although often uncertain with facial features, Pippin here has beautifully conveyed with the lightest brushwork the expression of someone who is lost in thought or possibly brooding. The man is black, and black and white viewers alike probably cannot help feeling that the picture, while not obvious, conveys something of the weight of being black in America. If the brown overcoat and cap that the man wears suggest that he is a veteran, that only adds to the picture’s being a presentation of a dilemma, because history records that African-American vets who wore any part of their service uniforms in public, especially in the interwar years, could by this very act spur white rage.

But as with all Pippin’s best pictures, no one meaning stands out. Without putting aside the social and political associations that the painting stirs up, a viewer may firstly, and lastly, be drawn to the work by the artist’s nerve in making the bench an assertive red. This was Pippin’s idea, not that of the parks department of West Chester. Even if you are not familiar with his remark about Matisse’s color, it can make you think: that man puts the red in the right place.