From April 1992 until the summer of 1995, the newly independent republic of Bosnia endured the darkest violence to disfigure Europe since World War II. Bosnian Serb militias attacked the republic’s Muslim and Croat populations, killing tens of thousands of civilians. Their siege of the capital, Sarajevo, claimed more than five thousand civilian lives. The administrations of Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton took no decisive military action; they argued that there was no way to stop Serbian aggression without incurring an unacceptable number of American casualties. Colin Powell, who was chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under Bush, opposed committing US forces to war for what he called “unclear purposes.” William Perry, Clinton’s secretary of defense, explained that there was “no support, either in the public or in the Congress, for taking sides in [this] war as a combatant, so we will not.”

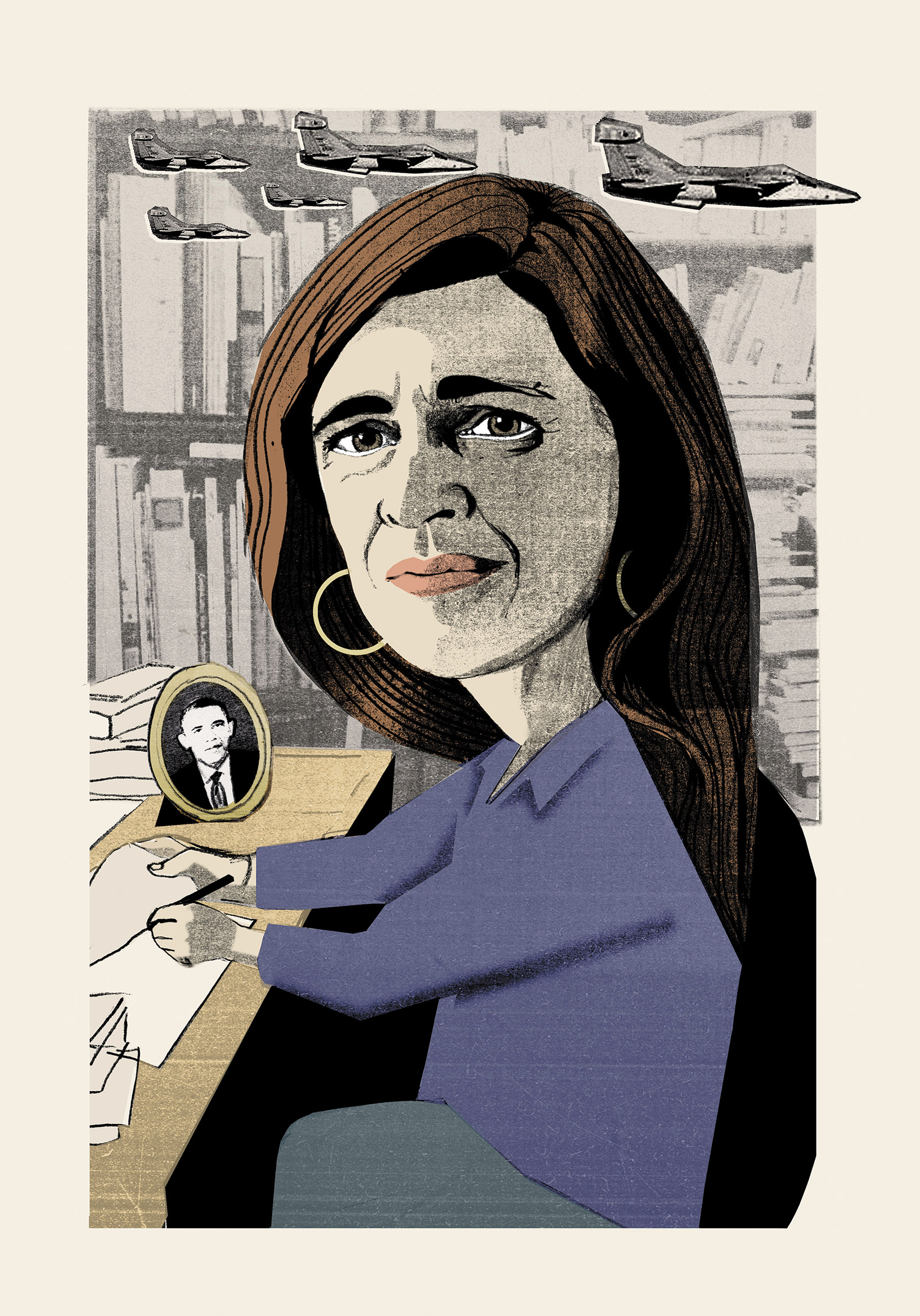

During the worst of the conflict, Samantha Power, an Irish-born American who was then in her early twenties and had recently graduated from Yale, moved to Sarajevo to work as a freelance journalist. As she documented the war’s cruelty—snipers picking off shoppers, shells smashing into schools and markets—she grew angry and then despairing about her government’s impotence. She came “to feel increasingly like a vulture, preying upon Bosnian misery to write my stories,” as she puts it in The Education of an Idealist, her recently published memoir.

Power decided to enroll at Harvard Law School. The war reached a turning point as she prepared to move home. In July 1995 Bosnian Serb authorities massacred more than eight thousand Muslim prisoners at Srebrenica, a slaughter that provoked public outrage in Europe and the US. At last, on August 30, NATO, led by the United States, launched a bombing campaign against Bosnian Serb targets. For just under three weeks, NATO bombers and cruise missiles badly damaged Serbian forces while suffering no combat casualties. After the assault, the Bosnian Serbs agreed to participate in peace talks, and in November, in Dayton, Ohio, the American diplomat Richard Holbrooke brokered an accord that ended the civil war. The agreement granted Bosnian Serbs territory captured through aggression, yet it stopped the violence, and the US deployed 20,000 troops to help keep the peace.

For Power, it seemed clear that many thousands of Bosnians had died unnecessarily because “realists” in the Bush and Clinton administrations had grossly overestimated the costs of intervention against the Serbs. After graduating law school, she directed a human rights center at Harvard and became involved in debates about how to strengthen the prevention of crimes against humanity and genocide. Power began research on what would become her magisterial history of failed US responses to mass atrocities after World War II, from Cambodia in the 1970s to Kosovo in 1999. Her book, A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide, came out in 2002 and won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction the following year. In the book’s conclusion, Power wrote that when the threat of genocide arises, the United States and its allies should create “safe areas” protected by air power and “well-armed” peacekeepers, and that the US “must also be prepared to risk the lives of its soldiers in the service of stopping this monstrous crime.”

Power’s work on human rights after Bosnia coincided with a period of unusual optimism among politicians, journalists, and human rights activists about the potential of the United States, European allies, and the United Nations to intervene in civil wars or against dictatorships to prevent mass atrocities, particularly since the paralyzing divisions of the cold war had vanished. As the millennium turned, Britain and the US championed a succession of armed interventions, rationalized in part on humanitarian grounds, that seemed to present prototypes of a new international emphasis on civilian protection. In 1999 an Australian-led force intervened to stop violence against civilians perpetrated by Indonesian militias; the operation secured the independence of East Timor, while suffering no casualties. The same year, NATO intervened to protect Kosovo’s ethnic Albanians from Serbian aggression; this time the bombing forced the surrender of Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic, creating a path for Kosovo’s eventual independence. (NATO suffered few casualties, but its Kosovo bombing campaign killed about five hundred civilians, according to Human Rights Watch.) In 2000 Britain successfully intervened in Sierra Leone’s atrocity-filled civil war, in support of a UN peacekeeping mission there; Britain suffered very few casualties and created conditions that led to the war’s eventual end. Notably, these interventions all involved powerful Western militaries intervening against weak opponents. This did not, however, stop some of the victors from extracting universal lessons for the future about the potential of outside intervention, including by military force, to stop atrocities and remove abusive regimes.

Perhaps the most influential apostle of humanitarian intervention at this time was Tony Blair, Britain’s New Labour prime minister. He offered an explicit philosophy of armed intervention to prevent genocide and mass atrocities against civilians and dismissed objections that military interventions in the name of human rights were just neocolonial power grabs enabled by moralizing rationales. “We live in a world where isolationism has ceased to have a reason to exist,” Blair said in a 1999 speech in Chicago that attracted wide notice. “We are witnessing the beginnings of a new doctrine of international community.” Blair did concede that “around the world there are many regimes that are undemocratic and engaged in barbarous acts,” so if coalitions of nations tried to intervene against all of them, they would do little else. To narrow the circumstances in which military intervention on humanitarian grounds might be justified, he offered a five-part test that asked whether diplomatic efforts had been exhausted and whether force was likely to work. For the briefest of periods, from the mid-1990s until the early 2000s, Blair seemed to have identified a creed that might rally the post–cold war world to a sustainable form of multinational policing to protect civilians facing mass murder by their own governments.

Advertisement

The September 11 attacks shattered some of this optimism. George W. Bush turned his administration’s attention to the threat of transnational, millenarian violence by small, stateless groups. Yet the ambition of the late 1990s lingered, certainly among Blair and his intellectual allies. When the United States and NATO invaded Afghanistan to attack al-Qaeda, they justified their assault on the grounds of self-defense against terrorists, yet there were many Western politicians—such as Hillary Clinton, then a US senator—who additionally welcomed the overthrow of the Taliban, al-Qaeda’s host, because of the Taliban’s barbarism and repression of women.

In 2002, as the Bush administration openly promoted an invasion of Iraq, the president and his supporters repeatedly identified self-defense against terrorism as their principal justification for war, pointing again to the threat of terrorist attacks as well as to Iraq’s supposed arsenal of weapons of mass destruction. Yet in addition to stirring fear, the president and his allies sometimes advanced the argument that Saddam Hussein’s overthrow would rescue the Iraqi people from terrible suffering. Indeed, Blair, now Bush’s most important international partner in preparing for war, promoted the justice and humanitarian benefits of removing Hussein’s dictatorship as a principal casus belli. On March 17, 2002, Blair wrote a confidential memo to his chief of staff, Jonathan Powell, discussing how Britain should separate its arguments from those of America:

From a center-left perspective, the case should be obvious. Saddam’s regime is a brutal, oppressive dictatorship…. A political philosophy that…is prepared to change regimes on the merits, should be gung-ho on Saddam…. So we have to re-order our story and message. Increasingly, I think it should be about the nature of the regime. We do intervene—as per the Chicago speech.

During 2002 and early 2003, Samantha Power was promoting A Problem from Hell. She had to address the awkward fact that her book examined Saddam Hussein’s 1988 genocidal campaign against Iraqi Kurds—and the Reagan administration’s passivity—as one of its case studies. Power had documented how Reagan’s aides contorted themselves to avoid protecting Kurdish civilians because, at the time, the threat of the Islamic Republic of Iran seemed to recommend accommodating Hussein, who would be able to counteract Iranian expansionism. Inevitably, Power was asked what she thought about George W. Bush’s intention to oust the Iraqi dictator. She writes in The Education of an Idealist that she was “uncomfortable about seeing my writing about atrocities used in a way that might help justify a war.” However, she did make clear her opposition to an invasion of Iraq. She told The New York Times in early 2003 that because the Bush administration “adheres to international law in such a selective way, it lacks the legitimacy to stand as the military guardian of human rights…. A unilateral attack would make Iraq a more humane place, but the world a more dangerous place.”

In 2005 Barack Obama, then in his first year as a freshman US senator, invited Power to dinner at a steakhouse in Washington. By then, Power’s—and Obama’s—opposition to the Iraq war had proved highly prescient. According to her memoir (she reports that she shared the manuscript with Obama before its publication), Power recounted how the Clinton administration’s decision in the summer of 1995 to use force in Bosnia had brought tears to her eyes when she first heard about it. “Why the tears?” Obama asked—“a bit coolly,” Power felt. “I guess relief that America had saved all those people,” she said. “Hmm,” Obama replied.

Obama expressed sympathy with those in high office who had had to decide whether to intervene in a civil war, noting, in Power’s summary, “how hard it must be to predict in advance exactly how local actors will respond to US involvement in a conflict.” Power soon joined Obama’s Senate office as a foreign policy fellow. She was eager, she writes, to “actually have the chance to influence the direction of US foreign policy.” Obama was skeptical of her entry into government. “You’ve got books to write,” he said. When she returned to Harvard, in 2006, he told her, “I don’t have the power to use you properly. I was actually wondering what took you so long to bolt.”

Advertisement

Yet her tour in Washington intrigued Power. The next year, she joined Obama’s presidential campaign as a volunteer; she hoped for his victory in part because she did not want to return “to the routine of academic life.” In an interview during the primaries, Power called Hillary Clinton a “monster” for her campaign tactics and had to step aside. But when Obama won the White House, she sought office. “I was tired of being a professional foreign policy critic,” she writes, “opining and judging without ever knowing whether I would pass the moral and political tests to which I was subjecting others. I wanted to be on the inside.” Obama initially appointed Power as a senior director at the National Security Council. She became ambassador to the United Nations in 2013, during the president’s second term. In both positions, because of her prior authorship and advocacy, Power became a bellwether for journalists and human rights activists who were trying to track internal debates about Obama’s willingness to use force to prevent mass atrocities against civilians.

Power’s exchange with Obama over dinner in 2005 foreshadowed their relationship. She was ardent; he was cerebral. It is a contrast that lends itself to caricature, yet it seems to have had a basis in truth. While at the NSC, Power was well removed from Obama’s inner circle on foreign policy. She sometimes used spontaneous, brief encounters with the president to discuss human rights policy, even as she recognized that this was perhaps annoying. She writes that Obama told her many times, “You get on my nerves.”

Across long passages of her memoir, Power seeks to describe how she learned to make what she came to think of as constructive compromises as a government servant. She writes that she never had favored military action as a primary means to address atrocities. Rather, she embraced a “toolbox” of statecraft to prevent mass violence, from aid to diplomacy to sanctions to public pressure—a toolbox in which force figured as an unwieldy last resort. She came to appreciate the mainly rhetorical achievements that can shape foreign policy. In 2011, for example, Power and her colleagues saw an opportunity to encourage Obama, in what would be a first for a US president, to advocate for LGBT rights during his annual speech to the United Nations General Assembly. After excruciating effort, she secured permission for a single sentence in Obama’s remarks: “No country should deny people their rights because of who they love, which is why we must stand up for the rights of gays and lesbians everywhere.” She celebrated this at the time while noting later that “discrimination and attacks against LGBT people still happen all around the world.” She concluded, nonetheless, that “just because we couldn’t right every wrong did not mean we couldn’t—or shouldn’t—try to improve lives and mitigate violence where we could do so at reasonable risk.”

Power seems to have accepted much of the president’s skepticism about America’s claims to righteousness in global affairs, his intense awareness of the unintended consequences of military action, and his determination to prioritize interests and evidence over an emotional impulse to act decisively whenever a humanitarian crisis erupts. Power quotes an Obama aphorism approvingly: “Better is good, and better is actually a lot harder than worse.” Power’s chronicle carefully charts Obama’s record on human rights promotion. It is notable for the wide gap between Obama’s exalted rhetoric during his years as a senator and a presidential candidate and his increasingly constrained approach once in the White House. In 2006, at a Washington rally called to address the crisis in Darfur, Obama told the crowd:

We know what is right and we know what is wrong. The slaughter of innocents is wrong…. Silence, acquiescence, paralysis in the face of genocide is wrong…. If we act, the world will follow! And in every corner of the globe, tyrants and terrorists, powers and principalities, will know that a new day is dawning and a righteous spirit is on the move, and that all of us together have joined hands to ensure that never again will these kinds of atrocities happen.

Obama’s speech upon accepting the Nobel Peace Prize in 2009, after he had assumed the presidency, was memorable but less far-reaching; he offered a principled defense of the use of force while rejecting, as Power puts it, a “false choice between idealism and realism.” Yet how false is it? In an age of American military hyperpower, in which the superiority of US arms allows a president to undertake all kinds of interventions with a reasonable likelihood of tactical success, the distinction between actions taken to defend what are perceived to be national interests and actions taken mainly to advance America’s founding ideals of individual rights is hardly an artificial one. As the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq showed, idealism and realism can blur into each other. Obama inherited these failing wars, and much of his record as a commander-in-chief concerns his attempts to wind down American involvement in those conflicts. But it is Obama’s decision-making during two other hellish civil wars, in Libya and Syria, that provide a contrast between his earlier rhetoric and his administration’s actions in opposing crimes against humanity.

In February 2011, two months after the start of the Arab Spring, popular protests erupted in Libya seeking the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi, the longtime dictator. Gaddafi ordered his troops to fire indiscriminately on civilians, killing hundreds. He vowed to “purify Libya inch by inch, house by house, home by home, street by street, person by person, until the country is clean of the dirt and impurities,” and he sent his forces toward Benghazi, a city of 600,000 and a seat of emerging political opposition. The possibility of mass slaughter seemed imminent.

Obama convened his National Security Council. Vice President Joe Biden, Defense Secretary Robert Gates, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Mike Mullen, and White House Chief of Staff Bill Daley argued strongly against military intervention. In Tough Love, her recent memoir, Susan Rice, then ambassador to the United Nations and later National Security Adviser, writes that this group of experienced hands protested that “Libya was not our fight and, effectively, that the likely costs of letting Gaddafi take Benghazi…were acceptable when compared with the risks.” Rice had been at the National Security Council during the Rwandan genocide, which haunted her. When her turn to speak came, she cited that example and supported action. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton also urged military intervention, as did Biden’s national security adviser, Tony Blinken, and Ben Rhodes, Obama’s communications adviser. Obama solicited Power’s views, and she concurred, warning him that “Qaddafi’s siege of Benghazi was sure to be savage.”

Obama decided to join a UN-sanctioned, multinational campaign to bomb Gaddafi’s forces from the air. “Some nations may be able to turn a blind eye to atrocities in other countries,” Obama said in a prime-time address. “I refused to wait for the images of slaughter and mass graves before taking action.” At no other time in his presidency did he so explicitly link military action to the prevention of an atrocity. Infamously, it did not turn out well. Benghazi was spared mass murder, if that is what Gaddafi’s forces intended. A Libyan mob eventually killed Gaddafi; a devastating civil war followed that has now lasted eight years and claimed thousands of lives. Power writes that “neither at the time nor presently” could she see how they could have taken a different course, and “no one can say with confidence what would have happened” if Obama hadn’t acted.

The mess that followed intervention in Libya clearly colored Obama’s calculations about Syria, whose own Arab Spring uprising devolved into a brutal multisided civil war in 2012. When Syrian president Bashar al-Assad’s forces used chemical weapons to suppress rebels, Obama declared a “red line,” threatening retaliation if Assad used gas again. On August 21, 2013, Assad’s forces did so in a rebel-held Damascus suburb, killing about 1,400 people with the nerve agent sarin. Obama considered air or missile strikes but ultimately deferred to Congress, which declined to act. Russia offered to oversee a program to destroy Syria’s chemical stockpile, and Obama seized upon this as better than a punitive bombing of Assad.

Power believed the president should have attacked Assad’s regime immediately after the August 21 attacks. As months and then years of debate about Syria dragged on, White House discussions “became circular and unproductive,” she writes. Several times, Obama “reprimanded” Power for “comments he thought were dogmatic or sanctimonious.” Once, he telephoned her to complain, “You are trying to tutor us as to why this is such a shit show…. People are heartbroken and anguished. I rack my brain and my conscience constantly. But I can’t answer in practical terms what we can do.”

The death toll from Syria’s civil war is today estimated at between 400,000 and 600,000. More than half of the country’s pre-war population of 22 million have become refugees, according to the UN. The migration of half a million Syrians into Europe during 2015 rocked the continent’s politics and stoked the rise of nativist nationalism and far-right extremism. The war also strengthened the Islamic State. The Obama administration provided substantial aid to Syrian refugees, and it took military action against the Islamic State, ultimately destroying its territorial caliphate. But Obama persistently declined to undertake a military intervention designed to protect Syrian civilians or to thwart Assad’s attempts to retain power in Damascus. Obama’s restraint evolved into a policy of passivity amid what turned out to be the greatest humanitarian tragedy that took place during his presidency—one whose geopolitical ripples damaged US interests in Europe and the Middle East. We will never know what a White House more inclined toward risk and action might have achieved, for better or worse.

If humanitarian interventions against sovereign states were merely a “newfangled experiment from the 1990s,” as Princeton politics professor Gary Bass put it in his important history of such actions, Freedom’s Battle: The Origins of Humanitarian Intervention (2008), then the post-Bosnia aspirations of Samantha Power’s generation of human rights idealists might be dismissed as a passing phase of internationalist naiveté. As the 2020 elections approach, it is hard to recall a time in postwar American diplomacy when human rights promotion and genocide prevention have seemed less salient. The rise of Donald Trump and other populist-nationalists in the West is one major reason for this, but in the United States liberals also increasingly advocate against intervention abroad and call for a reduction in the size of America’s military and the scope of its missions. Yet as Bass’s narrative of nineteenth-century interventions suggests, the impulse to use force to protect civilians abroad from mass violence is intrinsic to democracies whose constitutions privilege individual rights and liberties and declare them to be universal. For as long as America and the European Union remain attached to their founding ideas, the desire to export them will and should recur.

The optimism—and qualified success—of humanitarian intervention in the late 1990s can be understood partly as an accident of great-power history; Russia was prostrate politically and economically, and China was less powerful and more cautious than it is today. Partly, the run of interventions against weak opponents encouraged hubris. Obama wielded power in a different era—after the Iraq catastrophe, and while coping with Putinism and China’s ambitions.

Obama followed the pattern of the 1990s by authorizing interventions in places where the geopolitical stakes were low and the local opposition manageable, and the opportunity to save many lives was real. Following an Ebola outbreak in West Africa during 2014 and 2015, for example, Obama dispatched the US military, with the agreement of host countries, to provide medical and security infrastructure to battle the epidemic. The mission was self-interested, with the goal of containing Ebola before it could reach America, but it also saved many African lives and strengthened regional health systems beyond what was required to protect the United States. The more successful interventions involving militaries since the cold war’s end have had similar qualities: they seek to aid victims of natural disasters, disease, or refugee crises; they are as short and apolitical as possible; and they enjoy international legitimacy. Yet these criteria are hardly adequate to prevent powerful or deeply entrenched dictatorships or military regimes from carrying out mass atrocities or genocides against their own people, such as the ones the world watched take place in Myanmar, against the Rohingya, in 2015, and in Syria as the civil war there has continued.

Toward the end of her memoir, Power recounts a meeting she had in 2016 with Raed Saleh, the leader of Syria’s White Helmets, a civilian rescue force that works to dig out survivors in rebel areas after they are hit by government bombing raids. His organization had saved tens of thousands of lives since its founding in 2013. Saleh, pleading for American intervention, told Power that a thousand Syrian civilians had died in the week before their meeting. “Well, hopefully, we can…,” she began, and then she stopped herself.

She had nothing credible to say; they sat in silence. “I knew that neither the United States government nor the governments of other capable countries were planning to confront a scale of evil rarely seen in this world,” Power recalls with admirable honesty. “Syrian civilians were going to remain besieged until they surrendered to the Assad regime. And when they capitulated, even worse could follow.” She was hardly the only official drawn to the defense of Syrian civilians to be so disillusioned. Her assessment has proved darkly accurate.

And it requires an acknowledgment of accountability. The failure of the Obama administration to protect the millions of Syrian civilians caught up in a pitiless war at the crossroads of Europe and the Middle East was a foreign policy choice, reflecting Obama’s unwillingness to insist, as the leader of the world’s most powerful military and largest economy, that the protection of civilians and the prevention of the mass migration of refugees from Syria was as important to the United States as the destruction of the Islamic State. Power writes that she disagreed with some of Obama’s decisions, yet she defended the administration’s policy publicly. In her memoir, she certainly does not gloss over the consequences: “For generations to come, the Syrian people and the wider world will be living with the horrific aftermath of the most diabolical atrocities carried out since the Rwanda genocide.”

Power writes that she never seriously considered resigning over Syria; it isn’t fully clear why, but we can infer that she preferred her role as a collaborative policymaker seeking to achieve what was possible from the inside. We should admire the willingness of honest and idealistic Americans like her to serve in government. Yet the evidence she presents in her memoir about the American foreign policy machine’s ability and motivation to prevent genocide or mass atrocities in high-risk cases like Syria’s is very discouraging. This should not surprise us. In A Problem from Hell, Power wrote that America’s repeated failure to prevent genocide at times when rescuing victims was not politically popular at home or seen to be aligned with national interests has been a near-constant feature of our country’s statecraft. The Obama administration did not depart from this record, despite the idealism of Samantha Power, and notwithstanding the moral seriousness of the president she advised.