Some good news is that Penguin is bringing greater attention to Jessica Hagedorn’s Dogeaters with its celebration of the novel’s thirtieth anniversary, and it turns out that the book is every bit as spectacular as it was on its initial appearance. Although by the standards of both the serial-publication and the word-processor-enabled decades it’s a brief book, it is a mighty one; open it up, and a universe erupts from its modest 250 pages.

The story begins innocently enough: from an unspecified distance in the future, Rio, the book’s main narrator, looks back at an afternoon outing in 1956 with her cousin Pucha to see All That Heaven Allows, playing in Cinemascope and Technicolor at Manila’s Avenue Theater. Rio is ten and Pucha is fourteen, and they are chaperoned by Lorenza, Rio’s yaya, the family servant who looks after her.

After the movie, the three go to the Cafe España, where the girls, enraptured by midcentury Hollywood’s benign glossy dream clichés of love, America, and beauty, discuss the movie’s finer points over TruColas. To Rio’s distress, a group of boys at a table nearby start to flirt coarsely with the overdeveloped and somewhat under-brained Pucha. Worse, Pucha, obviously thrilled by the attention, cannot be budged from the café either by Lorenza or by Rio. The leader of the onslaught presses his advantage and Pucha “smiles back, blushing prettily”:

“Pucha,” I say with some desperation…. “What are you going to do—give him your phone number? You mustn’t give him your phone number. Your parents will kill you! Your parents will kill me…. He’s only a boy. A homely, fat boy…He looks like he smells bad.” Pucha gives me a withering look. “Prima, shut up. Don’t be so tanga! Remember, Rio—I’m older than you…. I don’t care if he’s a little gordito, or pangit, or smells like a dead goat. That’s Boomboom Alacran, stupid. He’s cute enough for me.”

And with this blithely efficient introduction to the potency of the Alacran family name, we begin our descent into the maelstrom that doesn’t release us until the book ends. As we soon discover, the loutish Boomboom is the crude face of the Alacran family—the flip side of his sleek, charismatic uncle, Severo Alacran, from whom the cachet of the Alacran name derives. And why is Severo so powerful?

BECAUSE, they would say. Simply because.

Because he tells the President what to do. Because he dances well. Because he tells the First Lady off. Because he dances well and collects art. Because he calls the General Nicky…. Because he employs a private army of mercenaries. Because he collects primitive art, renaissance art, and modern art. Because he owns silver madonnas, rotting statues of unknown saints, and jeweled altars lifted intact from the bowels of bombed-out churches. Because his house is not a home but a museum. Because he smokes cigars. Because he flies his own yellow helicopter. Because he plays golf with a five handicap. Because he plays polo and breeds horses. Because he breeds horses for fun and profit. Because he is a greedy man, a generous man. Because his wealth is self-made, not inherited. Because he owns everything we need, including a munitions factory. Because he dances well: the boogie, the fox-trot, the waltz, the cha-cha, the mambo, the hustle, the bump. Because he dances a competent tango. Because he owns The Metro Manila Daily, Celebrity Pinoy Weekly, Radiomanila, TruCola Soft Drinks, plus controlling interests in Mabuhay Movie Studios, Apollo Records, and the Monte Vista Golf and Country Club. Because he conceived and constructed SPORTEX, a futuristic department store in the suburb of Makati. Because he was once nominated for president and declined to run. Because he plays poker and wins. Because he is short, and smells like expensive citrus. Because he has elegant silver hair, big ears, slanted Japanese eyes, and the aquiline nose of a Spanish mestizo. Because his skin is dark and leathery from too much sun. Because he is married to a stunning, selfish beauty with a caustic tongue.

Rio’s father, Freddie Gonzaga, is vice-president in charge of acquisitions at Alacran’s conglomerate, Intercoco—International Coconut Investments. Rio describes her father as a “privileged member and stockholder” of Alacran’s huge Monte Vista country club, “where the magnificent greens are rumored to be infested with cobras, and the high-beamed ceilings of the open-air dining pavilions are a nesting place for bats”:

Part of my father’s job includes playing golf from dawn until dusk every Saturday, and Sundays after Mass, gambling for high stakes with his boss Severo Alacran, the nearsighted Judge Peter Ramos, Congressman Diosdado “Cyanide” Abad, Dr. Ernesto Katigbak, and occasionally even General Nicasio Ledesma.

Rio’s greatest pleasure is to listen to a radio soap opera, Love Letters—readers are treated to delicious excerpts—along with her sweetly addled grandmother and the servants who congregate in the grandmother’s room for that purpose. She’s well aware of the class stratifications on display all around her, but like most fairly privileged children, she takes for granted her family’s degree of prestige and their position with respect to the levers of power.

Advertisement

For the most part, those we meet early in the book—habitués of the Monte Vista such as the Alacrans, the socialite physician couple the Katigbaks, and General Ledesma—are, along with Rio’s family and the family servants, the figures in her world. They are also the people who constitute, along with the unnamed president and his outlandish wife, the nearly invincible, mutually fortifying triad—the government, the wealthy, and the military—that is the gravitational center of power of the entire nation portrayed in the book.

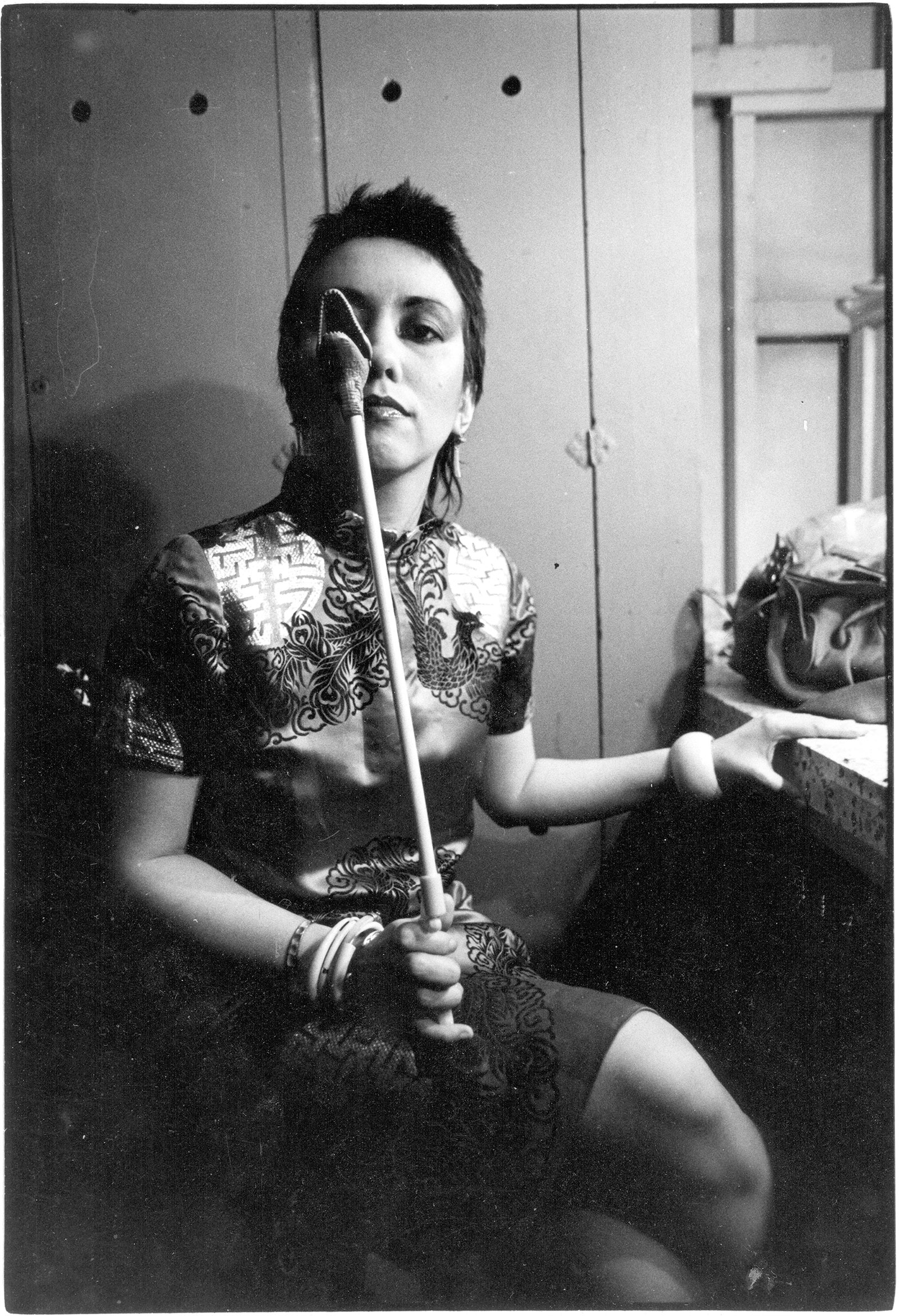

But the narration soon billows out beyond Rio’s consciousness. A resourceful, tormented street boy and a hovering omniscient viewer each take their turns with the story, and a richly informative current of gossip is overheard now and again. And soon we meet people who travel in various orbits around that center of power, people whom the child Rio would not have encountered: the General’s ambitious and murderous lieutenant; a number of actors, including a complicated, heroin-addicted movie star; a distinguished liberal/reformer senator, the public face of the political opposition; a rather mysterious Englishman with a penchant for Filipinas; the owner and patrons of a gay bar/disco; the “Barbara Walters of the Philippines”; an arty German filmmaker; a self-deceiving, desperate, and extremely unlucky young man from a small village—and plenty more from across the range of classes and the many, often reciprocally disdainful ethnicities.

As the book whirls along, the lives of these people intersect and sometimes collide. The web between them appears slowly and with an ominous clarity as we come to understand that we’re being acquainted not only with individual trajectories and the ways they fit together, but simultaneously with a map of social relations that expresses the inner logic of the president’s regime and the vast, stinging reach of authoritarianism.

Hagedorn’s stylistic flexibility—which moves gracefully between fast-paced storytelling, dreamy contemplation, satire, elegy, and visionary delirium—and her occasional inclusion of short texts that function more or less as chapter headings contribute to the book’s sweeping dimensionality. Some of these quotations are entirely fictional, such as clippings from the Metro Manila Daily, an invention of Hagedorn’s, but others are real. There are several from Jean Mallat’s 1846 volume The Philippines: History, Geography, Customs, Agriculture, Industry, and Commerce of the Spanish Colonies in Oceania, and there is one, a real jaw-dropper, from President William McKinley.

McKinley, perhaps best remembered for having been assassinated, was arguably the initiator of the United States’s imperial project; in 1898 he sent the US Navy on a roundabout course aimed at delivering Cuba from Spanish rule (into the hands of his own country), and on the way the convoy almost inadvertently took control of the Philippines.

Initially, McKinley had planned only to set up a base in Manila, but apparently decided that while he was at it, he might as well claim sovereignty over the entire archipelago—all seven thousand islands and seven million inhabitants. Over the course of this blood-drenched but strangely casual exploit, many atrocities were committed, which the American press—formulating disclaimers that have rung ever more loudly in our ears throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first—declared to be the work of a few bad apples, an aberrant departure from American values.

The capture of the Philippines, ratified by the dubious Treaty of Paris in December 1898, marked the first US acquisition of foreign territory. And read from our vantage, the section Hagedorn quotes from McKinley’s address in 1898 to a delegation of Methodist churchmen provides a classic lesson in the sorrowful, ludicrous ironies of hindsight:

I thought first we would take only Manila; then Luzon; then other islands, perhaps, also. I walked the floor of the White House night after night until midnight; and I am not ashamed to tell you, gentlemen, that I went down on my knees and prayed Almighty God for light and guidance more than one night…And one night it came to me this way—I don’t know how it was, but it came; one, that we could not give them back to Spain—that would be cowardly and dishonorable; two, that we could not turn them over to France or Germany—our commercial rivals in the Orient—that would be bad business and discreditable; three, that we could not leave them to themselves—they were unfit for self-government—and they would soon have anarchy and misrule over there worse than Spain’s was; and four, that there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them, and by God’s grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow men for whom Christ also died. And then I went to bed, and went to sleep and slept soundly.

Of course, the well-known intractability of the future rarely troubles the sleep of those who have the firm upper hand. And to be fair to the memory of McKinley, the Philippines achieved independence in 1946; the United States did not actually install Ferdinand Marcos.

Advertisement

The United States did, however, involve itself deeply with Marcos, who was, regrettably, president of the Philippines from 1965 until 1986. In fact, Marcos was highly distasteful to the American presidents who supported him—except for a starry-eyed Ronald Reagan, who adored him—and increasingly galling to the US businessmen with interests in the Philippines whose own (possibly themselves questionable) profits he siphoned off. But the strategic value of the Clark and Subic Bay military bases was such that the US compensated Marcos lavishly for his compliance, and he was guaranteed a long, rollicking joyride no matter how distasteful and galling he might have been.

The money the US poured into his hands, supplemented by what he squeezed from his own nation, he used partly to nourish his military and partly for some flashy monuments and infrastructure initiatives. Mainly, though, Marcos used American aid, along with the yield of Philippine resources, to stuff his own pockets. But in time, the very rapacity, looting, and brutality that stripped his country and rendered his people increasingly vulnerable to his repressions engendered a correspondingly determined insurgency. Inevitably, the cycle intensified, and in 1972 a series of bombings in Manila furnished Marcos with the opportunity to declare martial law.

The noxiously distinctive excesses of Marcos and his wife, Imelda, have secured them an enduring place in the public imagination’s gallery of ghoulish dictators, and Hagedorn pointedly models her president and wife on them. (It’s unlikely to be a coincidence that Hagedorn’s first lady is nicknamed the Iron Butterfly, as Imelda was.)

Like their fictional counterparts, the flamboyant First Couple of real life were free-spenders and party animals on a grand scale, and, predictably, various international socialites and celebrities piled onto the heap of people social-climbing all over one another. Van Cliburn, George Hamilton, and Cristina Ford, for example, were intimates of the Marcos’s, and they make cameo appearances in Dogeaters.

One pet project of Imelda’s was an astoundingly costly cultural center established in 1966, and its fictional mirror image in Dogeaters is harrowing:

The workers are busy day and night, trying to finish the complex for the film festival’s opening night, which is scheduled in a few weeks. Toward the end, one of the structures collapses and lots of workers are buried in the rubble. Big news. Cora Camacho even goes out there with a camera crew. “Manila’s Worst Disaster!” A special mass is held right there in Rizal Park, with everyone weeping and wailing over the rubble. The Archbishop gives his blessing, the First Lady blows her nose. She orders the survivors to continue building; more cement is poured over dead bodies; they finish exactly three hours before the first foreign film is scheduled to be shown.

Imelda Marcos was a great gift to American journalists, who never got a chance to interview Marie Antoinette. And Hagedorn devotes an entire dizzying chapter to a fictional American reporter’s efforts to gingerly extract from the fictional president’s wife a statement concerning the arrest and disappearance of an obviously innocent, ridiculously harmless, and utterly expendable young man who has been accused of the murder of a pivotal opposition figure:

Madame uses her favorite American expression as many times and as randomly as possible throughout her interview. “Okay! Okay! Okay lang, so they don’t like my face. They’re all jealous, okay? My beauty has been used against me… I’ve been made to suffer—I can’t help it, okay! I was born this way. I never asked God—” she sighs again. “Can you beat that, puwede ba? I am cursed by my own beauty.” She pauses. “Do you like my face?”

The reporter tries not to look astonished….

She appraises and dismisses him swiftly, noting his hairy arms, cheap tie, limp white shirt, and dreary wing tips….

The reporter keeps his voice steady. “What about the young man arrested by Ledesma’s men earlier this week?… Are any formal charges being made?”

Madame shakes her head slowly. She affects a look of sadness, which she does well. “You should interview General Ledesma and Lieutenant Carreon about that. These are terrible times for my country, Steve. Do you mind if I call you Steve? Good.” She pauses. “Ay! So much tragedy in such a short time! It’s unfortunate, all this violence. Thanks be to God for our Special Squadron, a brutal assassin has been apprehended…”

Marcos murdered and tortured swaths of dissidents, from far-leftist guerrillas to peaceful protesters, including moderates, Muslims, members of church groups, and students. And this he did with near impunity. It was only after his assassination of Senator Benigno Aquino in 1983 that Marcos’s excesses were judged too great an embarrassment and liability to his American protectors. By the time the United States cut off his support, billions in US dollars had simply vanished.

Before it became an occasion for Shock and Horror, the first lady’s astounding extravagance was, of course, no more of a secret than were her husband’s exhibitions of greed and cruelty. But when a despot has exhausted his utility to the United States and must be whisked away or allowed to be toppled, it has been the prudent practice to provide a justification, some “newly discovered” outrage that makes his overthrow palatable to the American public. And in the case of Marcos, there was an outrage ready to hand, as vivid, graspable, and unforgettable as an advertising jingle: his wife’s three thousand plus pairs of shoes!

In 1990, when Dogeaters was first published, however riveting as a work of fiction, the book would have seemed to address a fairly restricted political phenomenon; the whole category of “tyrant” seemed to be receding into the past. In 2020 we watch aghast at its resurgence.

Apparently it’s not so hard to destroy a democracy or to prevent one from developing. These days we’re seeing foolproof techniques deployed all over the place, including, again, in the Philippines: the dismantling of protections, the levying of viciously punitive measures, the curtailing or corrupting of the press, the sowing of confusion and discord, the folding of the justice system protectively around the upward consolidation of wealth, the criminalization and disenfranchisement of the already marginalized, the politicized use of the police, and so on.

And if the enterprise should run into difficulty, an aspiring tyrant can always declare an emergency that calls for the suspension of laws and the imposition of extreme measures. An occasion can always be found—a virus, for example, might turn out to be as useful as some bombings or a fire in a government building. In fact, it’s looking more and more—to more and more of us—as if we in the US have installed over ourselves our own mad tyrant.

But a tyrant must stay alertly poised between those whom he rewards and those whom he bleeds, and at a certain point, Marcos lost his balance and went down at the hands of both. Hagedorn portrays with great verve the few who thrive under the rule of her president, and she portrays with delicacy and conviction the transfiguration of several characters who for one reason or another exchange the life they’ve known for a more difficult, more dangerous, and no doubt more gratifying life devoted to loosening his lethal grip.

What is harder to understand when a repressive regime has taken over is the behavior of those who carry on with their lives more or less as before—an entrenched middle that’s decreasing in size, to be sure, in our part of the world and in many others, but one that is still large enough to provide a significant buffer around those who call the shots.

Many of us in my generation grew up bewildered by the apparent passivity of an astonishing number of ordinary Europeans during the years of Adolf Hitler’s triumphs: Were people terrified into submission, willfully blind, profoundly obtuse, befuddled by propaganda, enthusiastic about the policies of the Third Reich, clinging to fragile comforts, or what? In what ways and by what means were so many people paralyzed or bought off into inaction? What did these people say to themselves—how did they describe to themselves what looks from a distance like nothing other than pure complicity?

And, most mystifyingly and significantly, how is it possible not to know something that’s right in front of your eyes? What preconceived model is interposed between reality and what one perceives? That is to say, what does “not knowing” something mean?

In bad times, such questions are as urgent as answers, and Hagedorn is adept at portraying this middle zone of passive, everyday involvement, too. Here’s a little bit from a family gathering in which Rio’s family chats about a rumor that the whiskey that General Ledesma supplies to his troops is counterfeit:

“Papi,” Mikey says to his father, “they say the soldiers don’t know the difference, and they’re grateful!… The putok is so terrible, their guts rot and burn, and they wake up with killer hangovers. They say that’s why Ledesma’s men stay mean-spirited and ready to kill—” My cousin Mikey says all this with admiration. My brother looks impressed. Pucha leans over to whisper in my ear. “This is so boring. I think I’m going to vomit.”

“The General is from a good family,” Tito Agustin says to my mother. “Do you remember the Ledesmas from Tarlac?”…

“What about those camps?” my brother Raul suddenly asks.

“What camps?” My father is annoyed. Tita Florence and my mother seem perplexed, while Pucha looks bored. Uncle Agustin keeps drinking.

“The camps,” Raul repeats…. “You know—for subversives. Senator Avila’s always denouncing them—he calls them torture camps.”

“Senator Avila,” Uncle Agustin groans. “Por favor, Freddie—how about another drink?”

“Senator Avila has no proof. It’s those foreign newspapers again—”

“American sensationalism,” Uncle Agustin agrees.

“Does anyone want more coffee?” my mother wants to know.

“How about you, Agustin?” Tita Florence gives my uncle a meaningful look. Uncle Agustin ignores her.

“Boomboom Alacran went to the main camp, just to see for himself….”

“Boomboom’s full of shit,” Uncle Agustin says, smiling. He lights a fresh cigar.

“AGUSTIN!” Tita Florence’s hand flies to her watermelon breasts in a gesture of dismay. “Your language—the children!”

A friend once characterized Ivan Turgenev’s marvelous First Love as something beautiful made out of ugly things, and it has subsequently struck me that most really good works of fiction might be described in that same way. Hagedorn unwaveringly paints a menacing world, one that should sound an urgent alarm to us now—but the book is so beautiful! It’s painted in the shimmering, fierce, lush colors of memory and longing; it has the radiant evanescence of a dream—and it leaves behind the lingering authority of a dream’s veiled warning.