Bryony Lavery’s 2018 play Slime revolves around seven young interns at the Third Annual Slime Crisis Conference, which takes place at an unspecified time in a not-too-distant future. It is a multispecies gathering, convened in response to a toxic slime that is taking over the world’s oceans. The interns’ job is to interpret the squawks, squeaks, and groans of the cormorants, seals, guillemots, toads, and other animals in attendance, and to encourage all species to participate in the proceedings. While these efforts meet with mixed success, the idealistic translators see their work as a righteous cause. “We’re second-generation Animal communicators…so like…linguistically evolved,” says one:

We’ve benefited hugely from that really brilliant major paradigm thought shift…from “animals can’t talk”…to Humans actually pouring resources into learning their languages…their rich complex fantastic communication skills…understanding what animals tell us.

Humans have spent decades trying to teach other animals our languages—sometimes for convenience or amusement, sometimes out of scientific curiosity—but we’ve made little effort to learn theirs. Today, as a virus from another species upends human society, the usefulness of communicating with animals on their own terms is suddenly more imaginable. Perhaps Slime’s translators, hauled unwillingly back in time, could facilitate conversations among all parties to our pandemic, revealing not only how an animal virus became a human virus but what animals need and want in order to sustain our coexistence: for example, as the philosopher Eva Meijer writes, “the ways they want to live their lives, what types of relationships they desire with one another and with humans, and how we can and should share the planet that we all live on.”

Meijer, a Dutch writer, musician, animal ethicist, and postdoctoral researcher in philosophy at the University of Wageningen, published her first book about interspecies communication in 2016. That book, Animal Languages, is now available in English, as is her more recent and more ambitious When Animals Speak: Toward an Interspecies Democracy. In both, Meijer uses a deliberately broad definition of language—one that includes gestures, songs, alarm calls, and other behaviors—to argue that humans should learn to understand what animals are telling us, for their protection and ours. For animals, as she writes, “have been speaking to us all along.”

Theorists of animal rights, most prominently Peter Singer and Tom Regan, have traditionally focused on the “negative rights” of animals, such as the rights not to be killed, tortured, or confined by humans.1 The field has paid relatively little attention to humans’ positive duties toward other animals—their responsibility to protect sufficient habitat for other species, for instance, or to consider their safety when designing buildings and roads. The assumption, and implication, is that the best thing humans can do to protect animals is to stay as far away from them as possible.

But animals are stuck with us on this planet, and we are stuck with them. They live with us in our homes, invited or not, and pass through our daily lives, noticed or not. They pester us, threaten us, entertain us, and, as we have been recently reminded, infect us—as we infect them in turn. Whether or not we eat them, we consume their habitats, and compete with them for resources. Some might well be better off without us; others depend on us for survival, and we depend on them. Like it or not—and some of them surely do not—we exist in relationship with animals.

The scholarly emphasis on negative rights, along with the work of animal-rights and animal-welfare activists, has arguably improved the treatment of domesticated animals in North America and Europe. Public opposition to animal cruelty is now widespread, and recent laws and policies have banned animal blood sports. The insights of advocates such as Temple Grandin have helped us imagine how other species experience the world, and begin to curb some of the most brutal factory-farming practices.

None of these advances, however, has changed our fundamental relationship with animals—which is hardly sustainable, ethically or otherwise. In Slime, when one of the translators finally succeeds in communicating with a bump-nosed parrotfish from the Pacific Ocean, the message is stark, delivered in dramatic terms: “You are helping Slime to kill us You You You Land Monsters!!! Why? Stop? Why? Change your swimming! Change your swimming! Change your swimming!!!!” Were Slime written today, it might include a line from a pangolin or a bat, warning that our heedless exploitation of animals carries deadly risks for all.

Meijer argues that ethical relationships between humans and animals—like all relationships—require communication, whether through words, sound, behavior, or other means. And because so many animals can intelligibly communicate their needs and wants, agreement and resistance, she proposes that they are, in a sense, political actors, deserving of a part in human political systems.

Advertisement

The best-known pairs of animal–human communicators have bridged the species gap using some form of human language. Alex the gray parrot and the animal psychologist Irene Pepperberg, who worked with Alex for more than thirty years, shared a vocabulary of about 150 English words. (Alex could also recognize and identify fifty different objects, make jokes, and correct his trainers’ mistakes.) Chaser the border collie, trained by the psychologist John Pilley, could identify and retrieve more than a thousand different toys by name and understand elements of English grammar. Koko the gorilla, taught a form of American Sign Language by the linguist Francine Patterson, could sign over a thousand words and understand two thousand spoken words.

Of course, animals can communicate with members of their own species, and do so in varied, sometimes astonishingly complex ways, many of which Meijer describes in both Animal Languages and the opening chapters of When Animals Speak. Prairie dogs use their twittering alarm calls to describe approaching humans in detail, including information about their size, the color of their hair and clothes, and any objects they might be carrying. The intraspecies conversations of octopuses, bees, and many birds follow a recognizable grammatical structure. Dolphins have unique names for one another, as do certain species of parrots, monkeys, and bats.

Humans do learn and employ elements of other species’ “languages.” Biologists use recordings of animal sounds to elicit responses from their subjects; birdwatchers mimic songbird alarm calls to draw their quarries into the open; dog trainers mimic alpha-dog behavior in order to command obedience. When Jane Goodall began her famous observations of chimpanzees in Tanzania in 1960, she earned the chimps’ trust in part by copying their behavior and pretending to eat their foods.

Only a very few humans have attempted to communicate more fully with animals in their own languages. In the 1970s, as Meijer recounts, the American anthropologist and psychologist Barbara Smuts spent two years immersed in the daily life of a troupe of olive baboons in eastern Africa, following them every day from dawn to dusk. Instead of trying to stay out of sight, as most wildlife researchers do, Smuts watched the baboons’ communications with one another carefully, without hiding her presence, and over time began to imitate their sounds and gestures. The baboons, she reported later, appeared to be trying to understand her despite her “outrageous human accent,” and as she adapted her behavior to theirs, she felt that she was beginning to see the world through their eyes. She learned to read the weather as they did and predict when the troupe would want to move before a storm.

Meijer does not propose that we infiltrate our local deer herds, though she would probably endorse the attempt. While the project indicated by her subtitle—of working toward an “interspecies democracy”—is radical, her suggestions for first steps are appealingly humble, including an example she recounts from her own life: adopting her dog Olli, who came from a Romanian shelter, she met him for the first time when he arrived at the Amsterdam airport, along with nine other dogs and two chaperones, in November 2013.

When Olli moved into Meijer’s house, he had little trust in people and little sense of how to act around them. Rather than simply trying to curb Olli’s disruptive behaviors, Meijer observed his reactions to different situations and tried to interpret them. Over time, she says, dog and human settled on a “common language” of words, gestures, and behaviors through which she could understand when he was nervous, bored, or joyful—and what he wanted to do about it. While the visible results of these negotiations differed little from those of traditional dog training, Meijer says she began to see her surroundings from Olli’s perspective. “His views, for example, on dog [leashes], the number of dogs in this city, cars, large noisy machines, humans, and houses has made me experience these in a different way,” she writes.

Such interspecies exchanges can have practical benefits for both parties. Meijer points out that animals considered to be pests—such as the geese that congregate on the rich grasslands around the Amsterdam airport, deer that mow down shrubbery, and elephants that trample crops—can often be persuaded to change their behavior once humans understand what the animals are trying to accomplish. In the Dutch university city of Leiden, where nesting seagulls became so numerous, noisy, and destructive that some local leaders proposed a shooting campaign, a national bird-protection organization proposed creating islands near the coast to serve as alternative nesting grounds, first testing out different locations in order to assess which ones the birds preferred. Similarly, Meijer suggests that stray dogs would be happier—and ultimately present fewer problems to humans—if animal shelters taught both dogs and people to safely coexist, then allowed dogs to come and go from shelters as they pleased rather than confining or killing them. (In Moscow, she points out, a few stray dogs have even learned to use the metro system, allowing them to sleep in the safer suburbs and commute to the city center to forage.)

Advertisement

Such measures may not, on the surface, appear particularly significant. Yet the incorporation of other species’ perspectives into what are usually assumed to be unilateral human decisions, Meijer writes, “can function as the starting point for envisioning new ways of interacting.”

The animal-welfare and animal-rights movements grew out of public concern about the suffering of domesticated animals, especially those used by humans for food and labor.2 Meijer, as an animal ethicist, is likewise focused on domesticated animals and those capable of adapting to human-dominated habitats—dogs, seagulls, geese, deer, earthworms. She touches only briefly on the implications of her work for nondomesticated animals—the millions of free-ranging species more sensitive to human activities—missing an opportunity to broaden its reach.

Advocates of ecological protection, much like advocates of animal welfare and rights, have focused almost exclusively on what humans should stop doing: stop destroying habitat, stop destabilizing the climate, stop driving other species into extinction. They have, in general, been slow to recognize that preventing extinction, whether of whales or dragonflies, is necessary but not sufficient—that only when animal populations flourish can they survive more or less independently from us.

Despite this shared challenge, defenders of ecological protection and animal rights traditionally operate in isolation from each other—both intellectually and politically—and when they meet, they often disagree. Supporters of ecological protection, whether conservation scientists or environmental advocates, tend to see their counterparts as dangerously sentimental, willing to prioritize the survival of individual animals over the persistence of a species; supporters of animal rights, whether scholars or activists, tend to see theirs as heartless utilitarians, willing to tolerate the slaughter of individuals for an abstract greater good.

Both camps, however, aspire to an ethical relationship between humans and the rest of life, and to that end they need each other. Animal-rights advocates can help ensure that the large-scale culling of invasive animals—such as the extermination of introduced rats, cats, pigs, and goats that threaten endangered seabird species on many remote islands—is a last resort, undertaken only when less intrusive measures fail to stop a species’ slide toward extinction. Advocates of ecological protection can help ensure that captive-born animals are not freed unless they can survive on their own, and their new environment can also survive.

Meijer emphasizes that animals are not passive objects for humans to ignore or argue over—or collect, Tiger King–style—but “individuals with their own perspectives on life,” and members of communities with which our species coexists. That animals are in this sense political actors is an underrecognized and, to my mind, potentially powerful point of convergence between the animal-rights and ecological-protection movements: both traditions hold that animals have needs and wants that humans are more than capable of understanding, and should attend to.

The Canadian philosophers Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka, in their book Zoopolis (2011), proposed that humans treat nondomesticated animals as citizens of “sovereign communities” and domesticated animals as “full citizens of the polity.” While they acknowledged that most animals are believed to lack the capacities for self-reflection and political expression usually required for citizenship, they drew on disability-rights theory to argue that the interests of animal citizens could be represented by human guardians. Meijer takes this proposal even further, speculating that interspecies communication might advance to the point that animals reveal previously unrecognized capacities, and human guardianship of animal citizens becomes unnecessary.

Here, too, I think Meijer misses an opportunity. As the naturalist Henry Beston wrote in 1928, animals “are not brethren, they are not underlings: they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.” Even domesticated animals, as Meijer acknowledges, can form their own communities, establishing hierarchies and systems of reward and punishment. Instead of stretching the concept of human citizenship to include members of these “other nations,” why not focus on understanding other species’ societies?

Citizenship, after all, is not the only way to expand the political rights of animals within human society. In New Zealand in 2014, after a series of negotiations between the national government and the Maori people, Te Urewera National Park was replaced by a new entity, known simply as Te Urewera, that has the legal rights of a person. Three years later New Zealand’s Whanganui River, which people had developed for hydropower and polluted with urban effluent, gained the same status. Under the Whanganui agreement, two guardians—one chosen by the Maori and one by the national government—will act as legal representatives for the entire river system. In these cases, the rights granted are not citizenship rights, but more akin to universal rights possessed by citizens and noncitizens alike.

These and similar initiatives, though still in their early stages, could formalize a place for both domesticated and nondomesticated species’ perspectives in human society, and provide the “translators” needed to ensure they are heard—fostering the ethical interspecies relationships that, as Meijer argues, are crucial to us all.

Two other recent books explore the potential for greater interspecies communication, one through science and the other through a combination of science and music. In Animal Internet, the German writer Alexander Pschera reflects on the significance of the “digital revolution” in wildlife ecology—the recent explosion of small, relatively inexpensive cameras and satellite tracking devices that have allowed humans to follow animal movements in great detail.

Scientists are now collecting streams of data from tens of thousands of individual animals ranging from insects to snow leopards, many of them from species whose behavior was until recently largely unknown. Networks of motion-sensitive cameras have documented new species such as the grey-faced sengi, a giant shrew that lives in Tanzania, and rediscovered species long believed to be extinct, such as the silver-backed chevrotain, or “mouse deer,” a rabbit-sized, toothy mammal that lives in the lowland forests of southern Vietnam. Today, any smartphone user can track the progress of a single sea turtle as it migrates across the Pacific, or a seabird as it flies thousands of miles south for the winter. The ICARUS (International Cooperation for Animal Research Using Space) system, installed on the International Space Station in 2018, can pick up signals from tiny sensors attached to animals almost anywhere on earth.

While Pschera acknowledges the dystopian possibilities of these innovations—will animals, too, need data-protection laws, to shield their information from poachers?—the idiosyncratic essays in Animal Internet focus on their potential for changing humans’ relationship with the rest of life. Animal-tracking technology, Pschera believes, erases the perceived line between technology and nature, and between civilization and wilderness. “Technology is no longer the eternal adversary of nature,” he writes. Instead, “it has emerged as an ideal, adaptable interface between humans and their natural surroundings.”

This, surely, is far too optimistic. But the new avalanche of information about animals’ daily lives is certainly of practical use for conservation—it’s impossible to effectively protect a species if you don’t know where it goes in the winter, for instance—and Pschera suggests that it also has practical use for us: data on animal movements could provide early warnings of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, and could be used to study the spread of infectious diseases from animals to humans. He argues persuasively that the “animal internet” is full of possibilities for interspecies communication. Technology, in this case, could allow humans to temporarily adopt an animal’s perspective, seeing a near or distant place as a member of another species might see it. By acquainting us—via our screens—with the typical habits and behavior of other species, tracking technology can also teach humans to pay more attention to the animals we encounter in real life. As Pschera speculates, technological access to animals’ lives may, ironically, restore our sensory access to them.

Ecologists have long resisted the human tendency to anthropomorphize nondomesticated animals, perhaps fearing that we will imagine Cecil the lion, or Keiko the orca, or Diego the amorous Galápagos tortoise as something like a collective pet—an animal divorced from its habitat and its fellows, needing only our attention for survival. While the stories that emerge from animal tracking data do invite us to name and otherwise become attached to individual animals, Pschera argues that this is a potential boon for conservation, deepening and broadening humans’ emotional connection with other species. Today’s handful of animal celebrities might, with the assistance of technology, expand into a constellation of more familiar individuals—cherished ambassadors, so to speak, from other species’ nations.

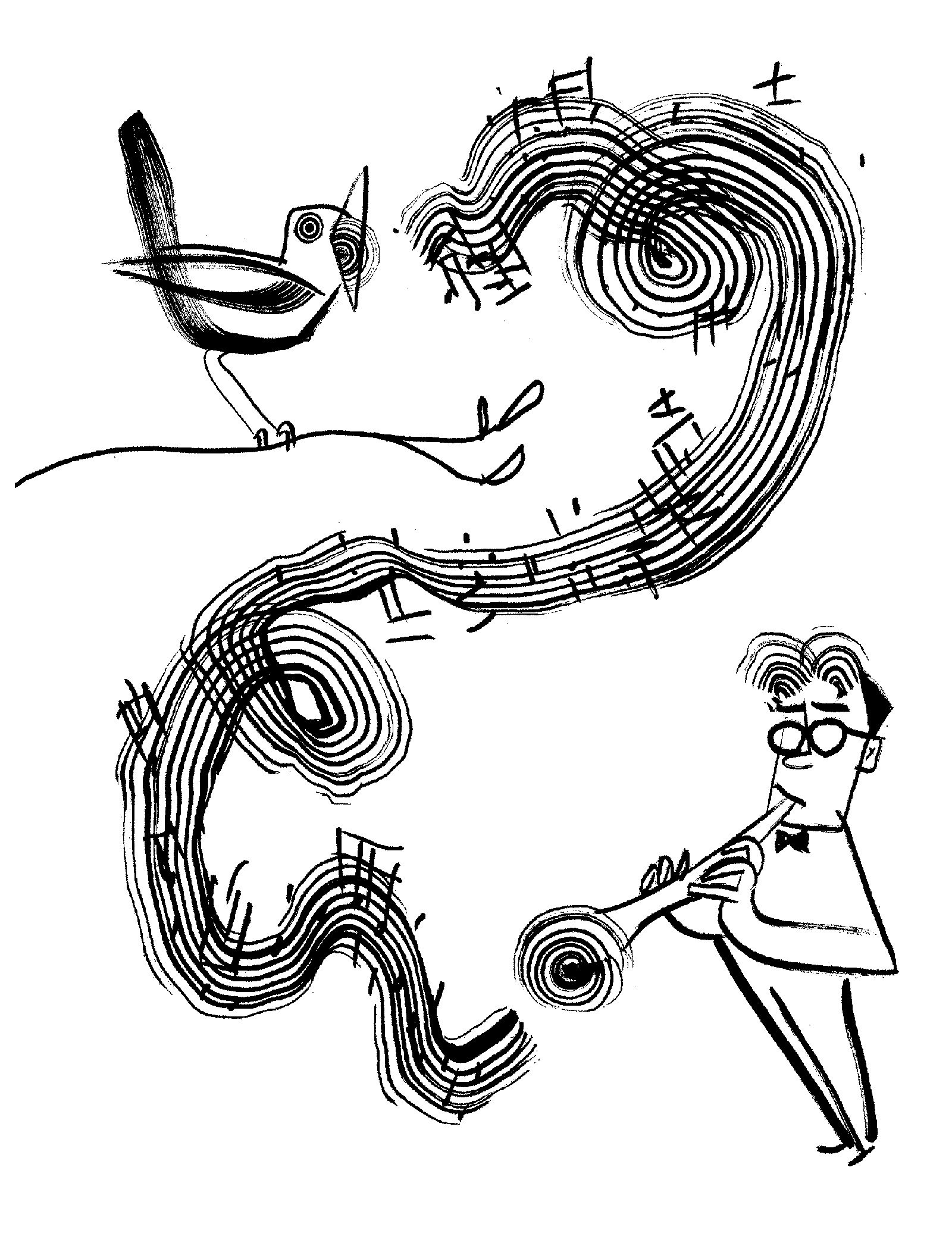

The American clarinetist David Rothenberg has performed with animals including birds, insects, and whales. In his short, charming new book, Nightingales in Berlin, he recounts his efforts to jam with one of the animal kingdom’s most flamboyant musicians. Every year between late April and late May, as nightingales return to Berlin from their winter migration to Africa, the male birds establish their territories, sometimes occupying the same roosts season after season. Each night, they defend their turf and attract mates with a loud, complex, and highly variable song that Rothenberg describes as “an unusual rhythmic assault.” A single nightingale can produce hundreds of different phrases, he writes, resulting in “a mix of rhythmic chirps, spread-out whistles, and funky contrasting noises neither mellifluous nor melodic.” In spite of—or maybe because of—the startling weirdness of their songs, nightingales have long been celebrated in myths and stories, and invoked by poets such as Shelley (“A poet is a nightingale, who sits in darkness and sings to cheer its own solitude with sweet sounds”) and Hafez (“The nightingales are drunk,/wine-red roses appear,/Sufis, all around us, happiness is here”).

Rothenberg is a professor of philosophy and music at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, and his book is in part a dialogue between art and science, between his attempts to understand the nightingales’ songs by immersing himself in them and scientists’ attempts to do the same by pulling them apart. When nightingale researcher Silke Kipper and her colleagues at the Free University of Berlin find that one distinctively buzzy tone is more attractive to female birds than any other sound in the males’ repertoire, Kipper wonders why the male birds don’t just keep repeating it: “Do they not know how well it works?” As a musician, Rothenberg thinks he knows why. The buzz, he speculates, is one of the nightingales’ riffs, a cool effect that loses its appeal if overused. “You’ve got to hold in your best licks, only letting them out when your audience least expects it,” he writes.

Rothenberg’s nightingale investigations lead him into extended conversations and collaborations with both scientists and musicians, and into recurring after-hours duets with the nightingales of Berlin’s Treptower Park. (Some of Rothenberg’s interspecies collaborations can be heard on the albums And Vex the Nightingale and Berlin Bülbül, both of which are fine accompaniments to the book.) He finds that in the spaces between the nightingales’ phrases, and the pauses in their back-and-forth with one another, he and the human musicians who join him can add their own improvisations. The result is a kind of music that no one species could make on its own.

Echoing Meijer, Rothenberg urges his readers to listen more closely to what other species might be trying to tell us. “It is always more and less than anything we can add to or take away from it,” he writes of the nightingale’s song. “Its rhythms are not boring, its melodies continue to surprise. We can never quite get it, this song intended for nonhuman ears.” Though our understanding of other species may always be hazy, we—and they—have much to gain from our attention.

This Issue

August 20, 2020

130 Degrees

Stepping Out

A Horse’s Remorse

-

1

See their exchange of letters in these pages on the tenth anniversary of the publication of Singer’s Animal Liberation (HarperCollins, 1975): “The Dog in the Lifeboat: An Exchange,” April 25, 1985. ↩

-

2

See Ernest Freeberg, A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement (Basic Books, 2020). ↩