I’ve never seen it mentioned in a book or magazine about home design, but among the greatest contributions to that literature is Zora Neale Hurston’s term “will to adorn.” She coined it in her 1934 essay “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” to describe a habit of embellishment she deemed central to African-American expressiveness. Hurston spots the trend in black vernacular locutions in which one word becomes two—“sitting-chairs,” “hot-boiling,” “chop-axe.” Likewise, when one decorative pocket hanging on the wall might do, there are several. Perhaps this “idea of ornament does not attempt to meet conventional standards,” she writes, “but it satisfies the soul of its creator.” To prove her point, she describes her visit to the home of a black woman in Mobile, Alabama:

The walls were gaily papered with Sunday supplements of the Mobile Register. There were seven calendars and three wall pockets. One of them was decorated with a lace doily. The mantel-shelf was covered with a scarf of deep home-made lace, looped up with a huge bow of pink crêpe paper. Over the door was a huge lithograph showing the Treaty of Versailles being signed with a Waterman fountain pen.

“The sophisticated white man or Negro would tolerate none of these,” Hurston notes, “even if they bore a likeness to the Mona Lisa. No commercial art for decoration.” But she was there to analyze, not cast aspersions. For Hurston, appreciating the aesthetic appeal of a butcher’s announcement and hanging a doily on a wall pocket—“decorating a decoration,” as she puts it—are instances of creative elaboration. “The feeling back of such an act,” she writes, “is that there can never be enough of beauty, let alone too much.”

This is a gratifying example of finding words for a form of everyday behavior that tends to defy articulation. As with deciding what clothes to wear before leaving the house or what to eat for lunch, the choices we impose on our living spaces are at once personal and inescapably social, a jumble of instinct and cultural expectation so complex that for most of us they play out, proprioception-like, beneath the radar of conscious thought. Until the fairly recent rise of environmental psychology and design psychology, much of the thinking and writing about this amorphous realm was confined to the bourgeois sensibility of “shelter magazines,” in which surfaces are served up as aspirational images and dissected according to principles of color, scale, and proportion, rather than mined for deeper meanings. If your desire for ornament extended to reading insightful discussion of it, literature was the main place to go—Edith Wharton wrote trenchantly on this subject, as did Virginia Woolf and Henry James.

At least, that’s how it was for me. I came across Hurston’s essay in early 2009, in the midst of the subprime mortgage crisis, which had felled the glossy shelter magazine where I’d worked as an editor. For the first time I felt more than mere witness to history—now both victim and participant. Though I was neither a predatory lender nor misguided buyer (I still rent my Brooklyn apartment), I couldn’t deny that my job had been to feed the fantasy machine. I thought often of a caption I’d composed for a photograph of a golden wastepaper basket that sold for $300. Did that handful of words not play at least a tiny part in the mass delusion?

My time in the luxury slicks gave me a surprising amount of practical knowledge about interior design and the decorative arts, and I remain in awe of the great practitioners in those fields, past and present, but I never lost my visceral dislike of how professionalized taste-making twists a fundamental human appetite for ornament into yet another locus of anxiety. Our country’s ongoing, cyclical battle between minimalism and maximalism (the “decor wars,” as I thought of them) seemed nothing less than a struggle over who gets to say what, and when, and why, masterminded by designers and, yes, editors who wield moral rhetoric—“authentic,” “artificial,” “too much”—to shame readers out of their own inclinations. Hurston’s “will to adorn” showed me that personal decor can also be a form of resistance, a happy refusal to button up and follow the rules; instead you can plant a flag on your own turf, add a flag on top, and then add one more for good measure.

Perhaps American consumers are susceptible to having “good taste” in decor imposed on them because design instincts tend to be dismissed as inconsequential at best, and at worst superficial. One source of blame is the Industrial Revolution. As gender roles calcified around the division of labor, and “home” became a woman’s sphere, safe from the ugliness and stench of the streets, it also provided a new outlet for self-expression through the buying and arranging of products. Until the 1800s it was architects—all men—who saw to a home’s design inside and out, proto–Frank Lloyd Wrights. But as the nineteenth century progressed, wealthy white society matrons sniffed a chance to busy themselves with something other than socializing, and the job of “decorator” was born. For the first time, the ability to arrange attractive living spaces was commodified and combined with “taste,” a concept grievously infused with economic hierarchies and racialized thinking. Edgar Allan Poe was on the case in his 1840 essay “The Philosophy of Furniture”:

Advertisement

A man of large purse has usually a very little soul which he keeps in it. The corruption of taste is a portion and a pendant of the dollar-manufacture. As we grow rich our ideas grow rusty…. But I have seen apartments in the tenure of Americans—men of exceedingly moderate means yet rarae aves of good taste.

The problem, as he saw it, was that we’d “fashioned for ourselves an aristocracy of dollars” to compensate for having “no aristocracy of blood,” and as a result habitually mistook the expensive for the good. Among a rising middle class, showcasing status via the “right” sofa and throw pillows became a national pastime, if not a secular religion, with the Sears, Roebuck & Co. Catalogue its bible. Where once a woman could cluck over her neighbor being late to church, now she could arch an eyebrow at her choice of window treatments, even if only glimpsed from the curb, and discuss the matter at length with friends over tea in the privacy of her own parlor, which naturally displayed only the “best” curtains, china, lamps, carpets, and wallpaper. Once the home was branded as female, taste inseparable from filthy lucre, and decorating a woman’s job—well, if you weren’t a furniture magnate, what was there about it to possibly take seriously?

The tradition of truly epiphanic, thoughtful writing about our relationship to the home seems confined to a hard-to-reach cupboard in which specialists might root around, rather than a central aisle that most of us will return to throughout our lives.1 Hence my delight over the new collection Lives of Houses, edited by Kate Kennedy and Hermione Lee, which brings together some of the best writing about the home that I’ve ever had the pleasure to read—and, crucially, loads of black-and-white photographs and illustrations.

In her preface Lee, who has written acclaimed biographies of Wharton, Woolf, and others (and is a frequent contributor to these pages), explains that the book arose from a 2017 conference hosted by the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing, which she founded in 2010 at Wolfson College, Oxford; Kennedy is its associate director. As Lee points out, writing about one’s own life or somebody else’s often involves writing about houses; biographers study them to better understand their subjects, and memoirists and autobiographers often begin their books with a memory of their childhood home (I can vouch for this myself).

The twenty essays and three poems included here adjust that relation: rather than passing through a house on its way to a person, each piece stays put, inspecting the various ways a home—or lack of one; homelessness, vanished houses, and asylums are also examined—shaped its inhabitant, from ancient Rome up to the near-present. The contributors are an eclectic mix of archaeologists, museum curators, historians, critics, and writers who train their gaze on the homes of poets, novelists, politicians, composers, collectors, artists, and, in two instances, those of their own. Less diverse are the destinations themselves, which are entirely Western, including Edward Lear’s Villa Emily, in San Remo, Italy; Yeats’s Thoor Ballylee, in County Galway, Ireland; and Edith Wharton’s The Mount, in Lenox, Massachusetts. That England figures disproportionally—Wordsworth’s Dove Cottage, in the Lake District; Churchill’s Chartwell, in Kent; and Benjamin Britten’s Red House, in Aldeburgh, to name a few—is easy to forgive, given the book’s origin. My selfish hope is that others will be inspired to create similar collections focusing on different parts of the world.

Kennedy and Lee pleasingly assert the freedom to consider not only houses, but also house-related themes. In the opening essay, “Moving House,” the British writer and landscape scholar Alexandra Harris, exhausted by her own recent move, explores what this chore was like for those before her, particularly during the Romantic era. Not counting the epigraph from John Clare (“I sit me in my corner chair/That seems to feel itself from home”), we hear first from Charles Lamb (“O what a dislocation of comfort is contained in that word moving”) and the eighteenth-century poet William Cowper (“The confusion which attends a transmigration of this kind is infinite, and has a terrible effect in deranging the intellects”), before setting off on an absorbing tour of “flitting.”

Advertisement

From the Middle Ages onward, tenants across Europe and Britain flitted once or twice a year, timed to the agricultural cycle, when they weren’t “moonlight flitting” (forced by debt to leave under cover of night). Cowper especially possessed a powerful affinity for the home, in both an emotional and material sense. “The presence of familiar items like cups and trays were to him the handrails of a narrow bridge or the bannisters of an agonisingly steep and long staircase,” Harris writes. “He sang the sofa with all the conviction Virgil had reserved for singing ‘arms and the man,’ insisting that the sofa mattered.” His long work The Task: A Poem, in Six Books—whose six parts included “The Sofa,” “The Timepiece,” and “The Garden”—was published in 1785, just before he left the house in Olney, Buckinghamshire, that he’d called home for eighteen years. Harris notes that “the set-piece celebrations of home life in The Task were purposely charming in their conversational ease, but layers of feeling were at work in them.”

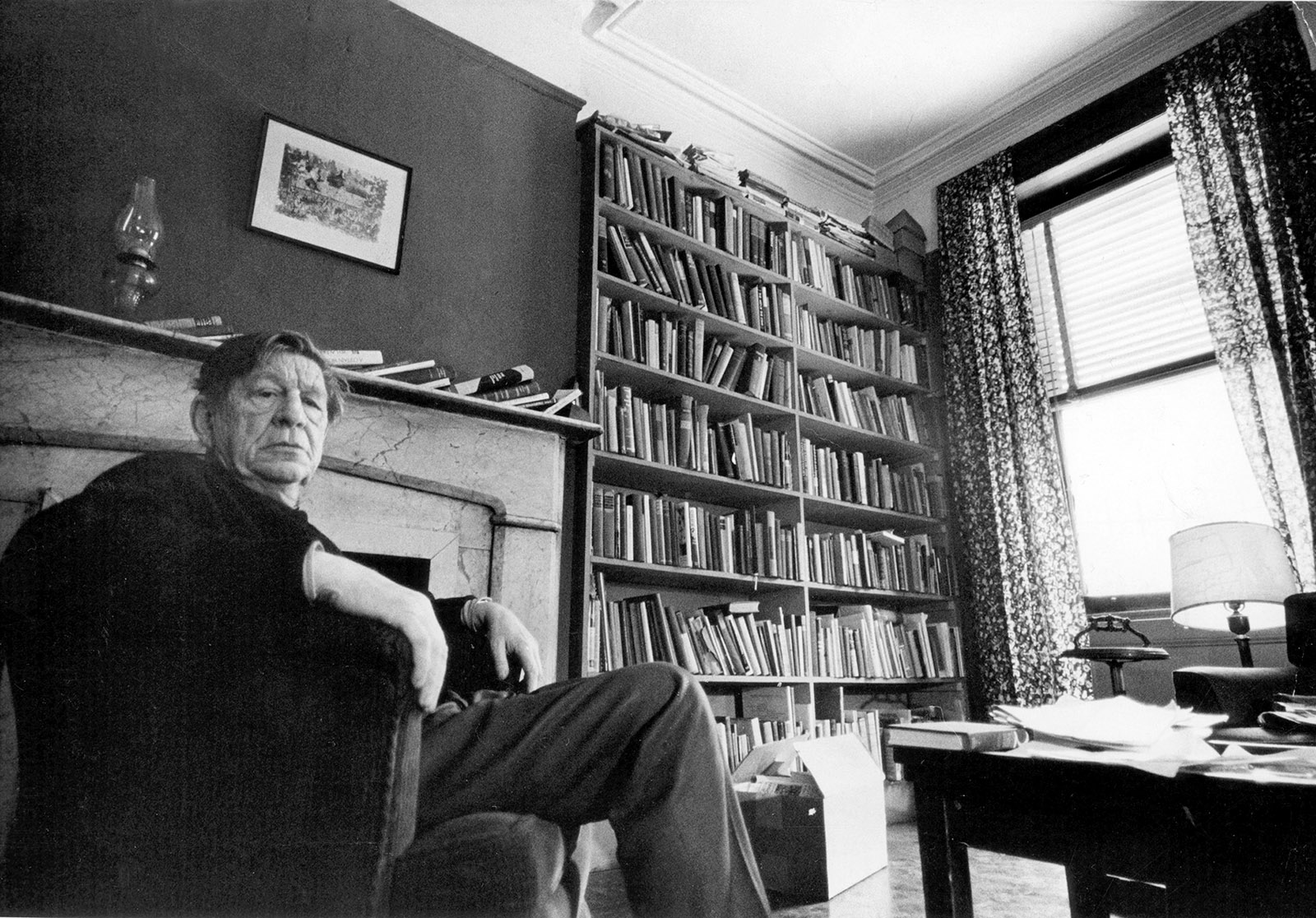

Another unexpected essay is the Oxford scholar Seamus Perry’s “77 St. Mark’s Place,” which was W.H. Auden’s address in the East Village from 1954 to 1972. Like moving house, disorderly housekeeping—that is, totally willful, even joyful, unabashed messiness—is not a subject I’d seen addressed in an essay before. Auden proves the ideal study. Edmund Wilson described his friend’s apartment as “uncomfortable, sordid, and grotesque”; Charles Miller claimed it “reeked of stale coffee grounds, tarry nicotine, and toe jam mixed with metro pollution and catshit, Wystanified tenement tang.” (The stench of urine likely featured in that bouquet; the poet preferred to relieve himself in the bathroom sink instead of the toilet, “a male’s privilege,” he once said.)

That upon moving there in 1954, Auden set his father’s barometer on the mantelpiece, and above it a watercolor painting, may not qualify as Hurston’s “decorating a decoration.” But as a small moment of orderly intention, this careful curation of a mini-tableau speaks to a heightened sense of decor in a man whose approach to homemaking was otherwise chaotic—on the surface, that is. Systems-wise, he was a domestic dominatrix. Chester Kallman, his life partner, nicknamed him “Miss Master” for being a nag. But Perry goes beneath the surfaces, exploring the relationship between Auden’s “fertile disarray” and his theories about poetics, which “repeatedly emphasise the importance of form and order,” as well as his expertise “in the infinite varieties of unrequited love” (to use Hannah Arendt’s words).

In her essay on Roman houses, Susan Walker, an honorary curator at the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, focuses on the fourth century, when the Roman emperor Diocletian, attempting to stabilize his empire, commenced a vast restructuring of far-flung outposts. In the process, the ancient city of Volubilis was abandoned. Yet judging from a ruin known as the House of Venus, Walker writes,

the move simply appears to have encouraged the privatisation of public space and the concentration of wealth amongst a few surviving individuals who were no longer accountable to the formerly ubiquitous Roman taxman.

Drawing on bronze busts and other relics that have been removed to museums, she walks the reader through the building’s layout—an orderly grid of stones, weeds, air, and “saucy” tesserae floor mosaics depicting mythological scenes. Its owner, she concludes, “was clearly a person of culture and no little wit, with ample financial resources,” who installed at least two separate chambers for the purpose of sexual encounters.

Visiting house museums has been a popular pastime in the United States since at least the 1850s, when the state of New York bought the stone farmhouse overlooking the Hudson River that George Washington used as headquarters toward the end of the Revolutionary War. In 1864, after Nathaniel Hawthorne died, tourists flocked to the little red cottage in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he’d written The House of the Seven Gables. (That house was eventually repurposed as practice rooms for Tanglewood musicians, but the colonial mansion in Salem, Massachusetts, that inspired the book has operated as a museum since 1910.) At last count there were more than 22,000 such history museums, historical societies, and similar organizations in the US, with house museums ranking as the most common among them. In 2002 Richard Moe, then president of the National Trust of Historical Preservation, tossed a bomb at his own industry with an article in that nonprofit’s quarterly publication, Forum Journal, titled, “Are There Too Many House Museums?”

Of course not. The problem is that they are so expensive to keep open, chronically underfunded, and reliant on volunteer staff—a set of circumstances that makes historical redecoration and adornment harder to keep in dialogue with other campaigns to spotlight and address longstanding economic and racial inequities. This is of special concern when you consider that at least one study found that Americans consider museums, of all kinds, “to be the most trustworthy source of information, more than movies, books, and professors.”2 The majority of house museums are devoted to white notables, and if gender parity isn’t exactly evident, quite a few women are represented. One can visit the homes of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Ernest Hemingway, Robert Frost, and even L. Ron Hubbard—as well as Pearl Buck, Rachel Carson, Willa Cather, and Emily Dickinson, and that’s just the beginning of the alphabet.

The list of African-Americans is short, but features the homes of Louis Armstrong, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Frederick Douglass, and with any luck those of James Baldwin and Nina Simone soon enough (those projects are both in progress). Also operating are sites that are committed to un-white-washing history, such as the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, Massachusetts, which explores the history of slavery in New England; the nineteenth-century free black community preserved at the Weeksville Heritage Center, in Brooklyn, New York; and the Tenement Museum on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, which brings to life multiple chapters of the urban immigrant experience—from 1864 to the 2010s—with a collection of more than five thousand domestic artifacts that furnish apartments to look and feel exactly as they would have in their own time.

In “A House of Air,” Lee reflects on the writers’ houses in America, France, Ireland, and England that she came to know through her work as a biographer. She notes that pilgrimages like hers are attempts “to understand the life of the other person, to find out more about them—and to pay tribute…. A strong but muddled impulse, a mixture of awe, longing, desire for inwardness, and intrusive curiosity.” I would add that such trips humanize those who live in our minds as legends. I appreciate how seeing where Georgia O’Keeffe or D.H. Lawrence lived and worked discourages me from regarding them as idols who hovered above the fray, free from quotidian concerns like scrubbing a pot. Writing of Samuel Johnson’s house in London, Rebecca Bullard, a writer and associate professor of English at the University of Reading, notes that “homes reveal the most authentic version of a biography’s subject, free from mannered or even hypocritical public behavior.” For decades and centuries, the personal lives of prominent figures were protected from scrutiny on the grounds that what happens behind closed doors was “private” and therefore sacrosanct, even when those private doings, no matter how nefarious, were an open secret among colleagues and whisper networks.

Regardless of what is being preserved, house museums offer an incomparably atmospheric experience, a series of unexpected intimacies impossible to replicate in biographies or documentaries. My visit several years ago to Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Steepletop, in Austerlitz, New York, where she lived with her husband (and, for a while, her lover) was full of such frissons. The house and grounds have remained basically untouched since her death in 1950. Wandering through her gardens, I smelled the scents she’d chosen to surround herself with; inside the old frame farmhouse, I caught the slant of light through the bedroom window as she would have seen it. Standing in her study, surrounded by her books, I knew how comfortable it would be to sit in her armchair reading all day—and felt a pang to realize that, of course, the most recent volume there was published in 1950; our libraries stop when we do. I was particularly moved by, of all things, her white-tiled bathroom, with its monogrammed towels, half-empty bottles of witch hazel and prescription pills, and a standing scale (she was fastidious about maintaining her small figure). But last year the cost of keeping the place open finally came to be too much, and Steepletop was forced to close to the public.

Steepletop’s misfortune may be a harbinger of what other house museums will suffer during the coronavirus pandemic. Already news reports are sounding alarms for such institutions in Spain, Austria, Hungary, and England, where Charles Dickens’s London house, kept intact since 1925 through an independent trust and ticket sales, could shutter as soon as September. Recently the Tenement Museum, which relies on admissions and gift-shop sales for more than 75 percent of its revenue, had to enact major layoffs and furloughs. But hope springs eternal. On July 2, after buying and meticulously restoring Mary Heaton Vorse’s dilapidated house in Provincetown, Massachusetts, the new owner, Ken Fulk, opened its doors as a residency program for local and visiting artists of all kinds.

Fulk is a San Francisco–based interior designer known for his deep knowledge of the decorative arts and his celebrity-studded client list. That he’s spending his free time maintaining the legacy of an early Greenwich Village labor reporter and social critic, with the hope that her genius for community activism will electrify our current moment, calls to mind another unexpected creative haunting, between Zora Neale Hurston and the musician and composer George Lewis.

He was a boy when Hurston died and a young man when her books came back into print. Her “Characteristics of Negro Expression” got him thinking about “adornment as a compositional attitude,” and “decorating a decoration” as a “recursive move,” he explains in the liner notes to his album The Will to Adorn, a set of four chamber works. Lewis suggests that listeners “imagine the music as a response to the complexity of the scene that greeted Hurston in her fieldwork.” The boisterous, decoration-strewn title track was performed and recorded live in 2011 by the International Contemporary Ensemble at Columbia University’s Miller Theatre, just around the corner from where Hurston studied anthropology with Franz Boas in the 1920s. Let that trajectory help bury the calumny that design instincts are among the lesser pursuits. Visionaries don’t just happen to live in homes; they also—to varying degrees—make those homes speak particular languages.

This Issue

August 20, 2020

130 Degrees

Stepping Out

A Horse’s Remorse

-

1

A starter library might contain: The Decoration of Houses by Ogden Codman and Edith Wharton (1897); The Domesticated Americans by Russel Lynes (1957); The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard (1958); An Illustrated History of Interior Decoration by Mario Praz (1964); Home: A Short History of an Idea by Witold Rybczynski (1986); At Home: A Short History of Private Life by Bill Bryson (2010); The Making of Home: The 500-Year Story of How Our Houses Became Our Homes by Judith Flanders (2014). ↩

-

2

See David Thelen and Roy Rosenzweig, Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life (Columbia University Press, 1998). ↩