Coming of age, as I did, as an Ojibwe on the Leech Lake Reservation in northern Minnesota, I thought a lot about life in the “real world,” off the reservation. Out there, I thought, is where America happens. America was on my mind even though America didn’t think a whole lot about me or my tribe. At least the country and I had that in common: we both thought of Indian communities as in America but not of it; as little islands of suffering in a vast democratic sea. It took decades for me to see that I was wrong—that Indian communities were not merely victims of democracy, and America wasn’t merely something that happened elsewhere. Its ideals and depredations are born and reborn, endlessly, in our homelands. This strange relationship is nowhere more obvious than in the question of the vote.

Native peoples, en masse, didn’t secure the right to vote until the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, which passed, partially, in recognition of the vast number of Natives who volunteered to serve during World War I. Even the passage of the Citizenship Act did not guarantee full suffrage, which had to be fought for state by state for the next forty years. Utah became the last state to grant its Native population the right to vote, in 1962.

In the beginning, the Constitution counted enslaved black people as three fifths of a vote, while Native folk “not taxed” were written out entirely. The Dred Scott decision of 1857, while reaffirming the noncitizenship of black Americans, stated that Natives were not to be counted unless we were naturalized like foreign-born immigrants. We were excluded again with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the 14th Amendment two years later. In 1870 the Senate Judiciary Committee affirmed that “the 14th amendment to the Constitution has no effect whatever upon the status of the Indian tribes within the limits of the United States.” Yet we were subject to American law and endured some of the most punitive policies this country has ever carried out, including expulsion from lands east of the Mississippi, compulsory attendance at Indian boarding schools, the unlawful divvying up of Indian lands to “encourage” private ownership, forced conversion to Christianity, and regular punishment—like the withholding of food, clothing, and shelter despite treaty-guaranteed access to all of it—if anyone was found practicing Native religions.

The Citizenship Act was a big step forward in ensuring that we could participate in our own future—and, more surprisingly, that we could continue to shape, if not control, America’s future. The truth that eluded me when I was growing up is that America—despite its blind use of force and its shrill insistence on the rights of the individual—has been shaped by us as much as we’ve been shaped by it. The Constitution was, in part, modeled on the separation of powers found in the political structure of the Iroquois Confederacy; an early test of the relationship between states’ rights and federal power was not over slavery but over Indian removal in the 1830s; starting in the mid-1960s the Supreme Court heard a shocking number of cases about federal Indian law involving treaty rights, sovereignty, jurisdiction, and tort; since 2015, the resistance of the Standing Rock Sioux and allied tribes to the Dakota Access Pipeline has kept the conflict between the common good and corporate greed at the forefront of American politics.

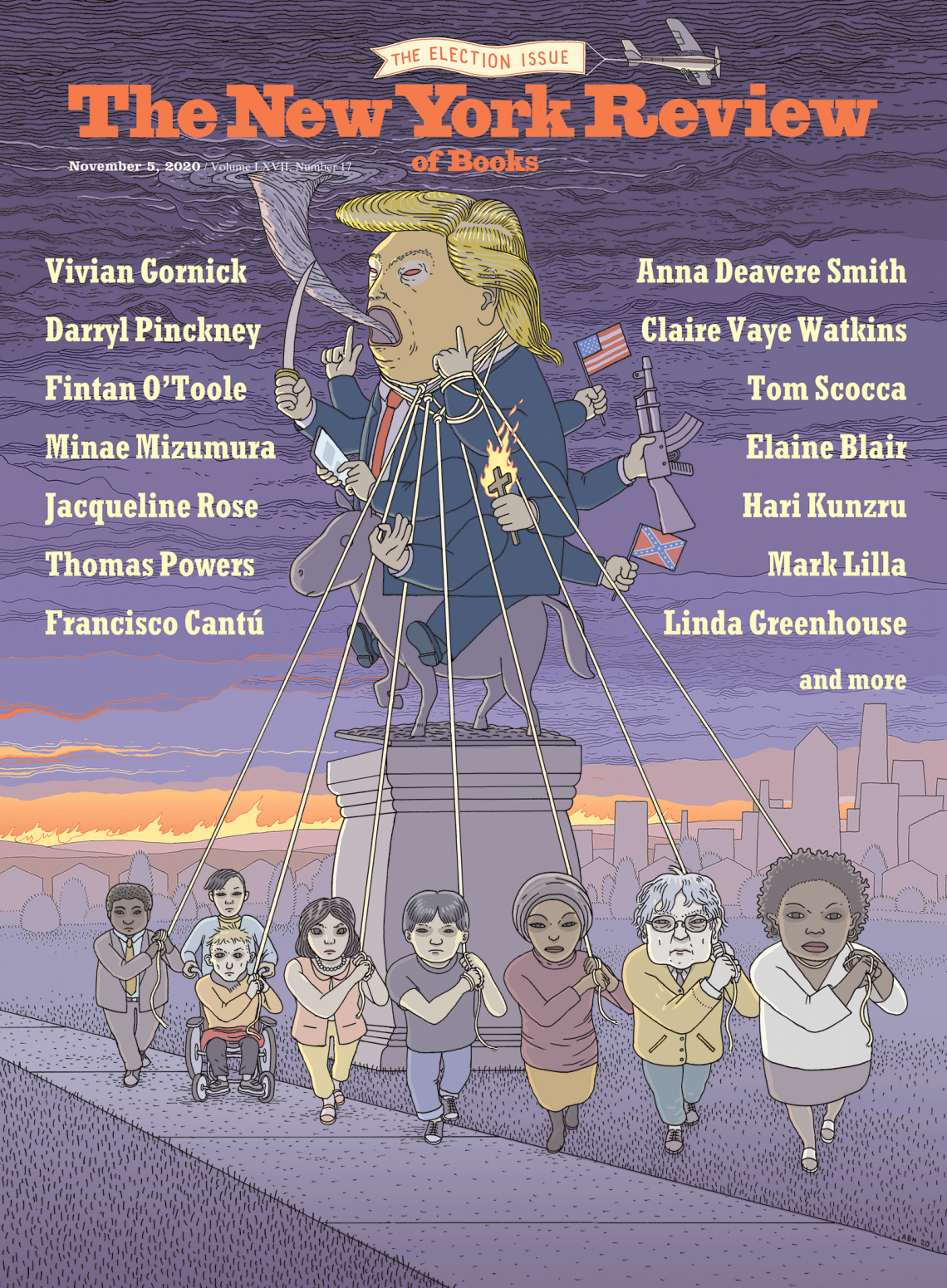

The election of Donald Trump in 2016 set Native people back as much as it set the entire country back. And it was apathy and cynicism on the part of many Americans that put us there. Cynicism, it should be said, is not a politics. It is a luxury enjoyed by those for whom “policy” is a rumor, or something that happens “out there.” But for Native people and other groups at the margins, policy is the shape and horizon of our lives. The decisions of the body politic are borne by the bodies of the vulnerable: A living wage. Access to education. Access to capital. Clean water or the lack thereof. Infrastructure and transportation. Affordable healthcare. If you want to see the real-world effects of policy, visit a reservation. Or your neighbors. Or the heartland. To say “Oh, it doesn’t matter who’s in office, they’re all the same” is to say that these problems don’t matter, and that we—the majority of Americans for whom American life increasingly resembles American Indian life as it’s been lived for the past 244 years—don’t matter. But we do matter. If you think otherwise, you yourself have become a victim of democracy.

What I see when I’m back home on the reservation, and as I look back over our lived history, is that Native people—against astonishing odds—have largely refused to fall into cynicism. We have always been and remain committed to one another and to a better future. So do yourself a favor: when you vote against Trump, remember that you’re also voting against the thin satisfactions of the self in favor of our shared ideals and the common good.

Advertisement