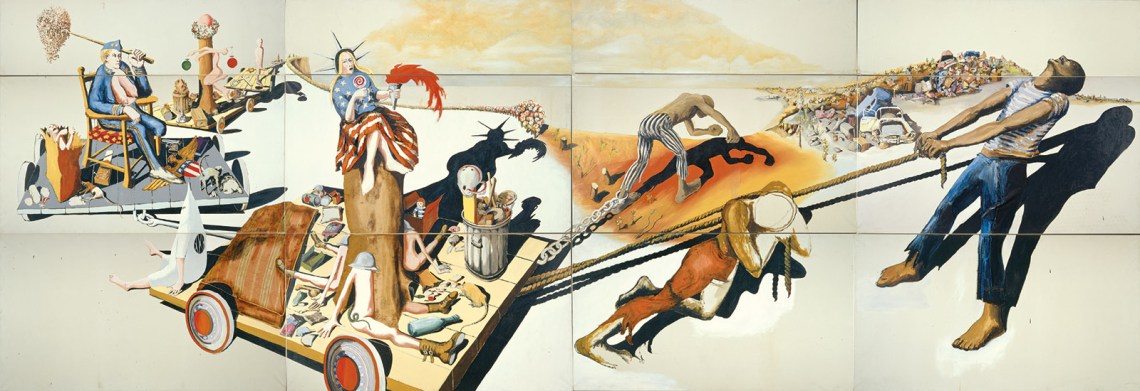

Benny Andrews Estate/The Studio Museum in Harlem/© Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Benny Andrews: Trash, 1971. A selection of his work is on view in ‘Benny Andrews: Portraits, A Real Person Before the Eyes,’ an exhibition at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York City, September 26, 2020–January 23, 2021.

“Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well?” asks the healer Minnie Ransom in Toni Cade Bambara’s 1980 novel The Salt Eaters, set in Georgia in the 1970s. “Just so’s you’re sure, sweetheart, and ready to be healed, cause wholeness is no trifling matter.” Minnie is speaking to her friend Velma Henry, who has suffered a severe mental and physical breakdown. Velma is a deeply committed and indefatigable African American1 civil rights activist, wife, and mother, but incessant meetings, disappointing fundraisers, and protests met with violence and mass arrests have left her exhausted, disillusioned, and enraged. Near the beginning of the novel, she attempts suicide. Minnie asks Velma the same question in different ways throughout the novel, prompting Velma to reflect on what it would take for her to feel complete while confronting multiple forms of oppression. The question is simple, and yet it holds within it a radical potential: an understanding of justice as healing, as both individual and collective, as something beyond mere survival.

William A. Darity Jr. and A. Kirsten Mullen don’t begin From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century with quite so coy a question, but they share with Minnie Ransom a vision of radical justice: to heal the United States of centuries of racial trauma. Darity, a professor of public policy at Duke, is an economist whose prolific writings focus on ethnicity, race, and inequality. Mullen is a folklorist, the founder of both Artefactual, an arts consulting practice, and the Carolina Circuit Writers, a “literary consortium that brings expressive writers of color to the Carolinas.” She has worked with museums and other public history sites, for instance helping to develop the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Darity and Mullen lay out a history of America’s failures to live up to its democratic ideals and its long record of state-sanctioned violence against and exploitation of African Americans. The early section of their book outlines a history of the reparations movement and tentative precedents to recompense African Americans for racist violence and exclusion after emancipation. Its lengthy midsection outlines a self-described political history of the United States, beginning with the institutionalization of chattel slavery, which turned people into property and stripped Black people of their humanity. Racial inequities have endured long after the formal end of slavery; its legacies persist to the present day. Finally, in the last two chapters, Darity and Mullen present a blueprint for “a just and fair America”: a detailed plan for calculating and administering reparations.

The most basic definition of “reparations” is payment to make up for a past wrong. When invoked as a mechanism of redress for American slavery, the word ignites passionate responses from advocates and critics alike. Darity and Mullen propose a “portfolio of reparations” that includes a mix of monetary payments, public services, and education. The monetary aspect is crucial from the first line of their book, an opening salvo as much as a statement of fact: “Racism and discrimination have perpetually crippled black economic opportunities.”

Darity and Mullen trace the movement for reparations from the end of the Civil War, describing freedmen and freedwomen as “the nation’s earliest architects of reparations.” Freedpeople demanded land to provide for their families and as compensation for generations of unpaid labor. Other demands included pensions for former slaves and refunds of millions of dollars in lost bank deposits following the 1874 closure of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Bank, better known as the Freedman’s Bank, due to mismanagement by its white trustees and employees.

In 1898 a seamstress named Callie House helped to form the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty, and Pension Association (NEMRBPA) in Nashville. House traveled the country to speak about reparations for slavery, attracting hundreds of thousands to the movement. In 1915, after Congress rejected several of her petitions, she sued the federal government. Her suit set the government’s debt for slavery at $68 million (about $2 billion in modern-day dollars2), a figure based on federal taxes collected on cotton in the 1860s. As her cause gained momentum, the government responded with repressive tactics; the Federal Pension Bureau and US Post Office, for example, denied mail service to the NEMRBPA. In 1916 House was convicted on dubious charges of mail fraud and imprisoned for a year. NEMRBPA branches continued lobbying for reparations into the 1920s.

The period from the late 1910s to the early 1920s brought racial violence that reached its bloody peak in the “Red Summer” and fall of 1919, when white mob violence erupted in more than two dozen cities and towns across the country. White mobs murdered and attacked thousands of Black people and destroyed (and stole) millions of dollars of Black people’s property. Subsequent court testimony, House Judiciary Committee hearings, and state-commissioned reports revealed the extent of the damage. A seven-hundred-page report by the Chicago Commission on Race Relations, for instance, recognized long-standing prejudice, police aggression against the Black community, and media manipulation of racial tensions as being ultimately responsible for the Chicago riot of 1919. The report also documented extreme economic disparities between white and Black Chicagoans. “Our Negro problem, therefore, is not of the Negro’s making,” it concluded. No state entity, however, went as far as to offer compensation to Black victims or their families.

Advertisement

Marcus Garvey, the charismatic nationalist leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), emerged after World War I as an outspoken advocate for building a separate Black nation. He was, like Callie House, convicted of mail fraud and sentenced to five years in prison. In September 1923 at New York’s Liberty Hall, while awaiting appeal, Garvey demanded that the United States, Great Britain, and other European countries

hand back to us “our own civilization.” Hand back to us that which you have robbed and exploited us of in the name of God and Christianity for the last 500 years…. And if you will not hear the voice of a friend crying out in the wilderness to hand back those things, then, remember, one day you will find, marching down the avenue of time, 400,000,000 Black men and women ready to give up even the last drop of their blood for the redemption of their motherland, Africa!

In 1927 the federal government deported Garvey to Jamaica, where he had been born. He died in 1940, but his message of self-determination continued to reverberate long after his death.

In 1955 the longtime UNIA member Queen Mother Audley Moore founded in New York City the Reparations Committee of Descendants of US Slaves. Moore presented a petition for reparations to the UN Human Rights Commission in 1959 that outlined the United States’ violations of African Americans’ human rights. The petition demanded land and payment for those violations. In 1962 she filed a lawsuit against the federal government on behalf of 25 million African Americans. Her suit sought $500 trillion in damages for slavery. Moore advocated for reparations until her death in 1997.

Moore’s activism dovetailed with the efforts of a chorus of Black churches, civic organizations, and communities during the civil rights and Black Power movements that pressed for reparations. Well-known leaders in these movements, including Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., spoke out. In Malcolm’s speeches and in his posthumous book By Any Means Necessary, he demanded that the federal government financially sustain a new, separate Black nation for twenty-five years, echoing Garveyism but also nodding to Black nationalist movements going as far back as the eighteenth century. He cited billions of dollars of aid paid to Latin America and European countries as an example of the US’s political will to help other nations—and he cited three hundred years of US slavery.

In his 1963 essay and then 1964 book, Why We Can’t Wait, King observed that even if a figure to recompense centuries of unpaid labor could be calculated, “No amount of gold could provide an adequate compensation for the exploitation and humiliation of the Negro in America down through the centuries.” King proposed a broad-based federal program and payments to eradicate poverty. While not a full-throated call for reparations, Why We Can’t Wait noted the pervasive and damaging long-term effects of slavery and racist discrimination.

The Republic of New Afrika (RNA), founded in 1968, put forth plans to create a separate nation-state within the continental US and sought $400 billion in damages for the violence and exploitation inflicted on African Americans. The RNA represented a group of activists who demanded that five southern states—Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina—be set aside for African Americans to establish the first district of New Afrika. In 1987 Imari Obadele, the longtime president of the group, and the lawyer and activist Adjoa Aiyetoro founded one of the most important organizations devoted to reparations: the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA). Similar to Callie House’s Ex-Slave Association, N’COBRA provides a formal organizational structure that knits together the decentralized reparations movement into a more cohesive effort. N’COBRA chapters spread across the United States, Great Britain, and parts of Africa.

In 1989 Democratic congressman John Conyers introduced H.R. 40, which called for the creation of a commission to study the legacies of slavery and develop reparations proposals. Conyers reintroduced the bill in Congress every year for nearly three decades. After he resigned his seat in 2017, Representative Sheila Jackson Lee became its lead sponsor. Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey is the lead sponsor of S. 1083, a Senate version of the House bill.

Advertisement

The reparations movement had achieved some successes by the last decade of the twentieth century, albeit limited ones. In 1994, responding to demands from the descendants of victims of the 1923 Rosewood Massacre, in which hundreds of whites killed an unknown number of Blacks and burned their Florida community to the ground, the state legislature approved a $2 million settlement and established a scholarship fund for those able to document direct lineage to a Black resident of Rosewood in 1923. State commissions formed to study the Wilmington Riot of 1898 and the Tulsa Race War of 1921 recommended payments to descendants of these racial pogroms, but neither the North Carolina nor the Oklahoma legislature has made any.

The movement has a slightly better record when demands for achieving reparations extend beyond recompense for white mob violence. In 1999 Pigford v. Glickman, a class-action lawsuit against the US Department of Agriculture, detailed decades of racial discrimination in USDA programs, such as USDA officials creating unnecessary delays in credit applications and outright denying loans that led directly to the loss of millions of acres of land. The courts awarded a $1.25 billion judgment. After a series of follow-up lawsuits, farmers and farm collectives began receiving monetary awards in 2013. The courts, then, looked like a promising arena in which to pursue reparations demands.

In the early 2000s advocates turned their attention to major corporations with links to profits from slavery, including the investment bank Lehman Brothers, the textile producer WestPoint Stevens, the insurance company New York Life, the mass-media conglomerate Gannett, and the railroad company CSX. The suits raised public awareness but didn’t result in monetary settlements. Incomplete records and multiple layers of corporate acquisitions, for example, made it very difficult to trace direct links to slavery profits. Defendants argued that slavery was legal at the time and that profiting from the institution, while morally reprehensible to contemporary sensibilities, was not then illegal.

Commission investigations into racially motivated violence and court cases that highlighted direct links to profits from slavery pricked some consciences. By the mid-2010s nine state legislatures had issued apologies for the part their states played in slavery and segregation. The US Senate and House of Representatives issued formal apologies for slavery in 2009, but they neither admitted financial culpability nor mentioned possible recompense.

Five years after Congress’s apology, the journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates published an essay in The Atlantic, “The Case for Reparations,” that galvanized national attention. In 2019 Coates and others testified before a House Judiciary subcommittee about H.R. 40. The hearing represented the most significant congressional consideration the bill had received in thirty years. The largest and oldest reparations advocacy organizations in the world—N’COBRA, the Caribbean Community and Common Market, and the National African American Reparations Commission—testified. More than one hundred human rights organizations, including the ACLU, Human Rights Watch, and the Japanese American Citizens League, signed a letter to congressional leaders urging the bill’s passage.

For Darity and Mullen, these attempts, so often tentative and isolated, have been dismal—hardly enough to address large-scale needs. Nothing short of “congressional action,” they write, will “ensure the provision of coverage and amounts of monies that meet the magnitude of the just claim.” But they are encouraged by recent political discussions about reparations during the 2018 midterm elections and 2020 presidential primaries. From Here to Equality went to press before the Biden/Harris ticket had even been nominated, but on Biden’s campaign website, under the heading “Lift Every Voice: The Biden Plan for Black America,” he pledged to study the issue if he became president. Now he will have that chance.

Darity and Mullen’s book comes, then, at a propitious moment. Moved by global Black Lives Matter protests during the summer of 2020, large cities such as Los Angeles and New York City have shifted funds from police budgets to education and other socially responsive efforts. Multinational corporations including Bank of America, Pepsi, and Apple have pledged millions for racial justice. Other corporations, nonprofits, and state and municipal governments have publicly announced financial commitments to address systemic racism. Important, too, is the growing body of scholarly work detailing the structural effects and personal costs of racist practices and violence, including, but not limited to, lynching, forced sterilization, redlining, slum clearance, mass incarceration, and police brutality. These efforts—some of them significant gestures while others are more furtive—signal that a serious conversation about large-scale reparations may be on the horizon.

I use “signal” here to reflect my guarded optimism. I wonder: Who makes decisions about how these dollars are spent? Who sets the priorities? More important, who benefits? New doubts and old questions remind us again of the complexities of repaying moral debts. And moral debts need to be paid. Apologies, commemorations, and plans go only so far. To be of any consequence, racial justice should be tied to thick folds of currency and the peal of hard coin.

Darity and Mullen would agree. In their estimation, the racial wealth gap is far more than the difference in dollars and cents between the haves and the have-nots. They forcefully argue that it represents “the most robust indicator of the cumulative economic effects of white supremacy in the United States” (emphasis in original). Accounting for the gap extends beyond a monetary figure. The gap translates to significant differences in well-being, in the very quality of a person’s life. ARC—“acknowledgment, redress, and closure”—argue Darity and Mullen, must also accompany any rigorous calculus of restitution and atonement for African Americans. The authors understand that the business of reckoning extends beyond writing a check, but a check must first mediate any negotiation between, in their words, the “wronged and the wrongdoers.”

After their lengthy recounting of US history and the history of reparations, Darity and Mullen present and dismantle several objections to reparations, ranging from obvious, reactionary questions to more thoughtful concerns. For example, in response to the claim that “Blacks already have received reparations from affirmative action,” they outline the limitations of such programs, explaining that the benefits of affirmative action accrue to an elite few, unlike reparations, which represent “an instrument for racial transformation.” To charges that paying reparations “perpetuates a crippling psychology of victimization among blacks,” they remind readers that interpersonal, institutional, and structural racism are responsible for Black peoples’ trauma—not an inherent, “alleged victimization mentality.”

In the last chapter of From Here to Equality, Darity and Mullen offer their detailed proposal for reparations, which shares some features with the Reparations Superfund, spelled out in James Forman’s 1969 “Black Manifesto” (corporations would endow the fund, and its resources would be allocated to initiatives in education, health care, crime prevention, and arts development) and N’COBRA’s reparations plan, which includes material reparations (such as cash payments and funding for repatriation), symbolic reparations (the creation of monuments and museums), and the elimination of discriminatory laws and practices.

Darity and Mullen’s proposal raises at least three critical questions: How much does America owe? Where will the money come from? And who gets paid? They highlight several possible ways to calculate the ultimate amount owed, including one based on a Confederate States of America figure setting the value in 1860 of enslaved people in the South at $4 billion (about $68 billion in modern-day dollars). They present the work of various historians and economists who arrive at figures as low as $14 billion and as high as $111 trillion.

These scholars’ reckonings derive from different interest-rate calculations on various valuations, including historical data such as profits from slave labor or unpaid wages; the value of diverted land, income, or employment discrimination; and differences in twenty-first-century per capita income. These calculations routinely disregard the humanity behind the figures being computed in ways that raise bile to my throat. Imagine: bread and medicine considered as expenses in the same way as coal for an engine or needles for an industrial sewing machine would be. These monetary figures, however, are one way to fathom the practical, if not the symbolic, value of slavery to the making of this country. For Darity and Mullen, most of these figures still fall short of capturing the full legacies of slavery and the contemporary effects of systemic racism.

Darity and Mullen are emphatic that the contemporary racial wealth gap represents the most important indicator of both the historical and the present-day harm to African Americans. They offer two possible inflation-adjusted figures that capture the size of the gap: $7.95 trillion and $10.7 trillion, which represents a direct payment of $795,000 each to an estimated 10 million African American households and a $267,000 payment to 40 million eligible African American individuals, respectively. It is important to stress that these figures reflect direct payments to individuals outside of endowments and funds earmarked for other initiatives in the portfolio of reparations they propose, which includes opening museums, support for historically Black colleges and universities, venture funds for Black businesses, and a minimum ninety-year educational program similar to the one proposed by WeRemember for victims of the Holocaust and their descendants.

To the second big question—where will the money come from?—Darity and Mullen frustrate this reader. They state that “many effective options for financing a program of black reparations” exist but then offer few details about the three possibilities presented: issuing new money, increasing government borrowing, or creating new taxes. They are clear, however, about who should raise and oversee administration of the funds: the US Congress. Congress is best situated, they argue, to conduct the critical research, generate political will, build public support, and create the infrastructure required for an effective reparations program. Corporations, universities, institutions, and even descendants of enslavers can certainly contribute to a reparations fund, but reliance on these entities to bear the brunt of the financial responsibility constitutes what Darity and Mullen describe as a “laissez-faire or piecemeal” effort: “We are not concerned about personal guilt; we are concerned with national responsibility.”

Regarding the last big question—who gets reparations?—Darity and Mullen outline three main requirements. First, eligible claimants must be US citizens, and then meet two more criteria: proven relation to at least one ancestor enslaved in the United States and self-identification as African American at least twelve years before the establishment of the congressional reparations commission. Having checked “Black” or “African American” on any official, government-issued document, including the census, will satisfy as proof of racial self-identification.

To be sure, elements of this plan are likely to raise eyebrows as well as hackles among those critical, questioning, or even supportive of reparations. Space prevents me from parsing every concern, so I will focus on one: Darity and Mullen’s definition of “the wronged” who deserve reparations. They use the racial identifiers “African American” and “Black” interchangeably, but the differences they mark aren’t merely stylistic choices. The “American” in “African American” really matters to the authors. Only US citizens with genealogical ties to enslaved people who labored in the United States count. Their requirement that only these African Americans receive reparations represents perhaps the most contentious element of their proposal.

Darity and Mullen reject the notion that the experiences of Afro-Caribbeans and other Blacks across the Diaspora living in the United States are “synonymous [with] the experience of…African Americans.” Their contention that “voluntary immigrants to the United States” (emphasis in original) make a conscious choice to live in a country that has benefited from racism means that these groups assume the debt their adopted country owes. The logic here is troubling on many levels, not the least of which is the assumption that immigrants don’t suffer racism and other forms of discrimination in the United States. Darity and Mullen try to smooth over the nativist implications by adding that reparations encompass collective, national redemption rather than individual, specific guilt.

The most serious flaw in limiting the deserving groups is that the authors’ plan ignores the history of enslavement in the United States, which extended to the Caribbean. The practice of slavery in both places was intimately bound together, even after the US won its independence from Britain. Darity and Mullen also ignore the aspects of slavery, particularly white supremacy and anti-Blackness, that animated twentieth-century US imperialism in the Caribbean, Latin America, and the Pacific. The Howard University historian Ana Lucia Araujo’s Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade: A Transnational and Comparative History (2017) is an excellent companion to From Here to Equality. Araujo details not only the centuries-long history of African-descended enslaved people’s fight for reparations in the United States but also the closely entwined relationship of US slavery with other parts of the world. True reparative justice must contend with the transnational legacies of slavery and with the centuries-long demands for reparations in the United States and throughout the world.

Darity and Mullen root their history of reparations after the Civil War, but the true starting point begins centuries before. From the moment enslaved Africans first set foot in the Americas, they grasped their own economic, political, and cultural value, and many early slaves were already thinking about what was owed to them for past labor. Indeed, during the Revolutionary era, enslaved people underlined their actual bondage, distinguishing it from the figurative British shackles the founding generation sought to shake off. Enslaved people’s freedom petitions to colonial legislatures traced the same longing for liberty as that of their disgruntled enslavers.

Some of these Revolutionary-era petitions acknowledged the economic stakes of liberty. In April 1773 a committee of four enslaved men in Boston speaking on “behalf of our fellow slaves” began their collective entreaty by flattering white legislators for their bravery and wisdom:

The efforts made by the legislative [sic] of this province in their last sessions to free themselves from slavery, gave us, who are in that deplorable state, a high degree of satisfaction. We expect great things from men who have made such a noble stand against the designs of their fellow-men to enslave them.

They comprehended the economic consequences of their petition and preempted the possible objections of legislators, some of whom were enslavers and most of whom derived some part of their livelihood from the business of slavery. The enslaved people wrote, “We are very sensible that it would be highly detrimental to our present masters, if we were allowed to demand all that of right belongs to us for past services; this we disclaim.” In rejecting reparations, these writers revealed a canny understanding of the marketplace of revolution, to borrow a term from the historian T.H. Breen: they showed that they were aware of their value and the concessions they could legitimately demand, yet they were willing to forgo reparations not because they didn’t think they deserved them, but to strike a shrewd bargain for their liberty.

Understandably, then, reparations’ accounting begins in enslavement. Mercantilist dreams and later capitalist realities commodified every part of enslaved peoples’ bodies and lives—including their lives before birth and after death. At every step of the trade’s supply chain, clerks, factors, merchants, enslavers, and other interested parties assessed the present and future value of slaves, as Daina Ramey Berry describes in her aptly titled book The Price for Their Pound of Flesh (2017).

Future increase, realized in the bodies of healthy babies and profits to be had from a lifetime of their labor, held important value. Would-be buyers groped the private parts of enslaved women and men, even children, up for sale. The buyers’ hands—rubbing, probing, squeezing—raped even as they claimed only to evaluate health and fecundity. The unborn was an important factor in an enslaved woman’s or girl’s total value.

Black women’s labor—both their physical working bodies and reproducing wombs—anchored slavery. Jenifer L. Barclay, a historian at the University at Buffalo, notes in her forthcoming book The Mark of Slavery: Disability, Race, and Gender in Antebellum America that some plantation ledgers assessed infertile women—rendered unable to bear children because of either genetics, age, or injury—as having a negative value because enslavers considered the cost of their care a liability. In Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology (2017), Deirdre Cooper Owens, a historian at the University of Nebraska, writes that Alabama enslaver James Spann valued an enslaved woman named Rose at $1—less even than two wooden tubs and a churn. Rose was either elderly or infertile, but her estimation reflected the diminished value of enslaved women who could not reproduce their enslavers’ capital.

In addition to commodifying future lives, the ledger demanded its grisly equilibrium on both sides of the column, even in disfigurement or death. The lure of profits in the transatlantic slave trade increased drastically when, as early as the fifteenth century, merchants could mitigate their risks and collect some return on their investment for enslaved property swallowed by the sea. Along with carefully worded contracts and lease agreements, particularly in the decades before the Civil War, enslavers relied on heavily ornamented insurance certificates to demand recompense for the injuries or deaths of enslaved people they leased to neighbors, public-works projects, foundries, and railroad corporations. Even cadavers and the body parts of deceased enslaved people could fetch a good price from private physicians and medical schools for study or display.

The accounting for the debt owed begins with slavery, but it doesn’t end there. Darity and Mullen miss some of slavery’s critical contemporary legacies. Jim Crow hardly respected geopolitical boundaries. For example, systemic racism and economic exploitation informed US imperialist projects in the Caribbean, Central and South America, the Pacific Islands, and other places around the world. In highlighting the import of the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery, Darity and Mullen give short shrift to its crucial codicil: “Except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” They mention convict-leasing and mass incarceration among the litany of abuses justifying reparations but don’t fully acknowledge the tendrils of modern-day slavery and mass incarceration that reach within and beyond the United States and that disproportionately exploit African Americans and people of African descent.

Finally, racism, anti-Blackness, and white supremacy invidiously work together to disadvantage many others besides African American citizens. Vigilante mobs never took the time to parse Black ethnicities or inquire about nativity when they visited death and destruction on Black communities. When politicians gerrymander, purge voter rolls, and rain taxpayer dollars on cherry-picked constituents, none makes exceptions for Black immigrants. Police clubs and bullets pay little attention to passports. Political expediency perhaps plays into Darity and Mullen’s decision to limit reparations to only African Americans descended from enslaved people in the US. But such a compromise undermines any legitimate claim for radical justice.

In Salt Eaters, the desperately unwell Velma Henry, after contemplating Minnie Ransom’s offer of wholeness, undergoes a communal process that involves other healers as well as medical professionals and neighbors. Illness is a social condition, and while Velma’s illness lies within her, it isn’t hers alone. It’s also a consequence of the world she lives in. True healing for an individual shouldn’t be separated from addressing malaise in communities, institutions, and structures, particularly the malaise that emerges from racism infecting the body politic. “Wholeness is no trifling matter,” Minnie insists. “A lot of weight when you’re well.” In From Here to Equality, Darity and Mullen challenge the United States to bear the moral weight of the legacies of slavery and deeply entrenched racism: to reject trifling, half-hearted measures and to approach—and perhaps even achieve—wholeness through reparations.

-

1

A note on racial identifiers: I use Black and African American interchangeably, depending on syntax. I do not hyphenate African American, even when used as a compound adjective. I prefer to capitalize Black as a proper noun when used as a racial descriptor to acknowledge the social construction of racial identity and African-descended people’s struggle for acceptance and recognition as citizens. I prefer not to capitalize white, not because it is not socially constructed, but because it has historically been a signifier of social domination and privilege beyond its role in indicating racial or ethnic origin. ↩

-

2

All modern-day dollar figures cited here are calculated using the Friedman Inflation Calculator at westegg.com/inflation. ↩