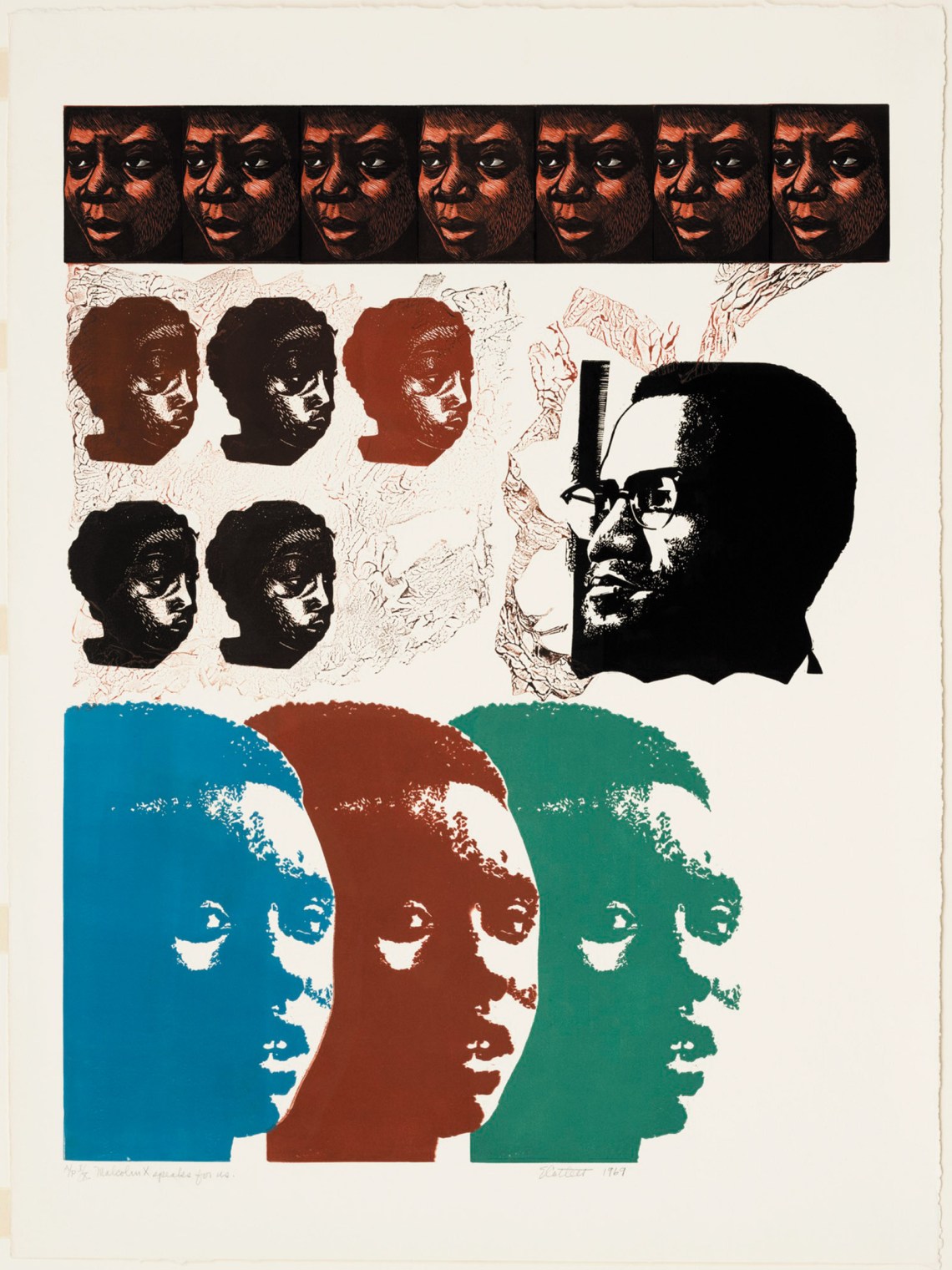

Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X met only once, at the US Capitol during the Senate debate over the 1964 Civil Rights Act. That chance encounter was immortalized in a photograph that shows the two men shaking hands and smiling but reveals little trace of the public feud that has linked them in our historical imagination. Their conflict has cast arguably the longest shadow over African-American politics and the struggle for racial justice of any contretemps since the one between W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington at the turn of the twentieth century.

Just a few years after King came to international renown as the spokesman for the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott, Malcolm delivered a star turn in The Hate That Hate Produced, a 1959 television documentary hosted by Mike Wallace, who introduced Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam (NOI) sect, to which Malcolm then belonged, as a living “indictment of America.” While Malcolm was most notorious for the prosecutorial zeal with which he cross-examined the propaganda of white supremacy, he also made attacks on King a recurring element of his rhetoric and transgressive allure. Malcolm charged King with being “cowardly” and “a traitor to his own people,” insulting him as an “Uncle Tom,” “handkerchief head,” and, most spitefully, “house Negro.” He suggested that King’s great betrayal was his promotion of a self-defeating philosophy of racial integration and nonviolence, which would ensure that its adherents suffered racial domination peacefully and without resistance.

Newspapers and magazines could not resist such a rivalry, nor could intellectuals obliged to adjudicate the dispute. Harold Cruse’s The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual (1967) treated Malcolm and King as emblems of the enduring struggle between “integrationism” and “nationalism,” which Cruse characterized as the central fault line of Black political life. Battles over such ideas, Cruse rightly noted, could be traced back to Frederick Douglass’s campaign against emigrationists like Martin Delany, who argued at times that mass flight from America was the best solution to the plight of black America, an oppressed “nation within a nation.” Recovering this past, Cruse and other historians placed Malcolm’s brazen, implausible defense of “Mr. Muhammad’s solution” of a separate Black nation-state in a sweeping historical context.

But for all of Cruse’s intellectual acumen and the more measured statements scattered throughout his book, his decision to foreground this grand narrative exacted severe damage on the popular understanding of Black intellectual and political life. Debates among Black thinkers on questions of gender, religion, democracy, internationalism, and, above all, political economy were reduced to an overarching struggle between two traditions.

After Malcolm’s and King’s assassinations in 1965 and 1968, this moralized opposition attracted a host of others. In popular and political culture, Malcolm and Martin represented not just separation and integration but hate and love, particularism and universalism, resentment and reconciliation, North and South, the street and the church, and, to King’s particular frustration, masculinity and effeminacy. The cumulative weight of these facile dualisms helped cement one of Black politics’ most enduring questions as a three-word loyalty test, as simple as it is bewitching: Martin or Malcolm?

In the first part of this review, I discussed Les and Tamara Payne’s biography of Malcolm X, The Dead Are Arising.1 For all the book’s virtues, the Paynes nonetheless reprise this Malcolm–Martin dichotomy with a script that is as false as it is familiar. While “King dedicated his lifework to hammering away at the segregator’s ‘false sense of superiority,’” they argue, it is Malcolm who “worked single-mindedly to help Negroes, the segregated, overcome their ‘false sense of inferiority.’” But King, at least as early as the Montgomery bus boycott, conceived of protest precisely as a way of showing reverence for Black dignity. Rather than nursing an obsequious focus on white racial attitudes, King fervently believed that African-Americans would “betray their own sense of dignity and the eternal edicts of God himself” if they were to acquiesce to racial domination without protest, even at risk to their lives.

James Baldwin, one of the few people who spent significant amounts of time with both men, showed greater fidelity to their complex thought in muddling this dichotomy. In a 1972 essay for Esquire, Baldwin provocatively wrote:

Malcolm and Martin, beginning at what seemed to be very different points…found that their common situation…so thoroughly devastated what had seemed to be mutually exclusive points of view that, by the time each met his death there was practically no difference between them.

This view of Martin and Malcolm as being pushed by circumstances toward a philosophical and political reconciliation has attracted a handful of prominent defenders over the years, including historian Clayborne Carson and the late journalist Louis Lomax. Yet it has never received as comprehensive and elegantly rendered a defense as it does in Peniel Joseph’s powerful dual biography, The Sword and the Shield.

Advertisement

Joseph, a prolific historian of twentieth-century African-American politics, an indefatigable public commentator, and arguably the leading chronicler of the Black Power movement, sheds light in The Sword and the Shield on the complex intellectual and strategic dynamics beneath the publicly fractious relationship between Martin and Malcolm. By uncovering the more subtle forms of influence they exerted on each other, Joseph aims to upend the depictions of Malcolm as “the political sword of the black radicalism that found its stride during the heroic years of the civil rights era and fully flowered during the Black Power movement” and of King “as the nonviolent guardian of a nation…[whose] shield prevented a blood-soaked era from being more violent.” For Joseph, these simplistic oppositions prevent us from reckoning with how Martin and Malcolm

traveled down a shared revolutionary path in search of black dignity, citizenship, and human rights that would trigger national and global political reckonings around issues of race and democracy that still reverberate today.

Joseph persuasively places each man at the center of the other’s most dramatic transformations. King’s later radicalism is unintelligible without grasping how Malcolm, primarily through his influence on the Black Power generation, shaped King’s views on civil disobedience, white supremacy, and, above all, American imperialism. Even more persuasively, Joseph shows how, despite Malcolm’s disparagement of political protest, a mix of envy and admiration for King’s commitment to direct action ate at his devotion to Muhammad. It is no coincidence, for Joseph, that Malcolm’s split with the NOI coincided with his declaration that “I am throwing myself into the heart of the civil rights struggle and will be in it from now on.”

Dispensing with the nationalism–integrationism dichotomy, Joseph argues that Malcolm and Martin converged around two ideals: “Radical black dignity” and “radical black citizenship.” The former involves the revaluation of Black identity and support for self-determination movements at home and abroad; the latter insists that questions of economic justice, civic participation, and the redress of racial injustice are crucial to being a free, equal member of the polity.

The question of dignity, as Malcolm appreciated, involves confidence in our moral standing as people who warrant equal respect and who are responsible for lives that are worth living well, with virtue and excellence. “So-called Negroes,” he proclaimed at Yale Law School in 1962, “not only have been deprived of their civil rights, but…have even been deprived of their human rights…the right to hold their heads up, and to live in dignity like other human beings.” The NOI argued that white supremacy determined value in ethics, politics, economics, and even aesthetics in the US. Railing against the chemical relaxing of kinky hair, skin bleaching, and other Black beauty practices as capitulations to white supremacy, Malcolm asserted that anti-Black racism had gone so far as to alienate African-Americans from their own bodies. In hating “our African characteristics…our features and our skin and our blood,” he said, “why, we had to end up hating ourselves.”

Under the influence of Elijah Muhammad’s racist metaphysics, Malcolm’s earliest responses to this degradation slid easily into a Manichaeanism that celebrated Black chauvinism as “racial pride” while judging whites to be “a filthy race of devils.” But after he publicly converted to Sunni Islam in 1964, Malcolm ceased defending what he began to deride as Muhammad’s “racism” and “racialism.” Recasting his intuitions about pride and dignity, the later Malcolm pointed to the practical need to shore up the social foundations of self-respect. We need to celebrate the historical achievements and cultural practices of people of African descent, he argued, because our judgments, habits, and expectations will otherwise continue to be shaped by the oft-unconscious inheritance of centuries of racist propaganda.

As Joseph details and the Paynes minimize, King shared this fundamental preoccupation with dignity. From the very beginning of his public career, he argued that under Jim Crow segregation, “many Negroes lost faith in themselves and came to believe that perhaps they really were what they had been told they were—something less than men.”

To meet this soul-corrupting threat, King often brandished philosophical abstractions drawn from liberal Christianity and Kantian universalism. In the midst of a sermon or essay, he could take flight, extolling the inherent deliberative capabilities of human reason, or celebrating that each of us is a bearer of imago dei. Amid the crossfire of political conflict, however, the organized contempt of white supremacy could make these presuppositions appear ineffectual, or at least inapposite. This, after all, was the concern behind Hannah Arendt’s insistence that “you can only defend yourself as the person you are attacked as.” “A person attacked as a Jew,” she warned, “cannot defend himself as an Englishman or Frenchman. The world would only conclude that he is simply not defending himself.”

Advertisement

Malcolm, who often proclaimed he was “not an American,” but “one of the 22 million black people who are the victims of Americanism,” left no doubt about the identity he thought best to invoke against anti-Blackness. His sense of Black identity as focal and fundamental inspired an explosion of Black Power organizing and debate that ultimately pushed King to publicly embrace a more detailed, particular, and politically potent account of what black dignity demanded. In Where Do We Go from Here? (1967), King candidly described blacks as besieged by racist ideologies that proclaim their “biological depravity,” cultural “worthlessness,” and physical ugliness while denying their claims for human recognition and equal respect. Though he never wavered in opposing political violence, he sounded suspiciously like Malcolm and his Black Power acolytes as he implored white liberals to see the “positive value in calling the Negro to a new sense of manhood, to a deep feeling of racial pride and an audacious appreciation of this heritage.”

Both men, however, understood that exhortations to pride were not enough. To overcome the humiliation and subjection of white supremacy, Malcolm argued that it was incumbent on African-Americans to defend the right of “self-determination…to direct and control our lives, our history, and our future”—for themselves, Africans, and other imperially dominated peoples.

Joseph’s book is especially excellent in the way it details Malcolm’s attempts to drag the provincial Nation of Islam beyond its fixation on an independent Black polity and toward a more serious understanding of geopolitics. Becoming a self-appointed international emissary of Afro-America and a devoted teacher of foreign affairs to Black audiences, he served as an NOI ambassador to the Middle East and Africa in 1959, orchestrated Fidel Castro’s controversial visit to Harlem in 1960, and had a crucial part in promoting protests against the CIA-backed assassination of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo in 1961. After he broke with the NOI, Malcolm used his newfound liberty to advocate for the United Nations as a possible means of protection and redress for African-Americans’ violated human rights.

King never seriously entertained the utopian ideas of Black emigration or the romantic racialism of Muhammad’s Black nationalism. Nor could his political realism permit him to be optimistic about the likelihood of the United Nations intervening on behalf of Black Americans, given the disproportionate power of US foreign policy elites in the Security Council and America’s coercive economic and military influence around the globe. Yet the extent to which King’s vision of justice exceeded the horizons of American nationalism is still perhaps the least appreciated element of his public philosophy.

For those used to seeing King situated in a progressive story of American liberalism, it can be surprising to learn that as early as the 1950s, he considered Black freedom struggles to be part of the wave of anti-imperialist revolt in Africa and Asia. “The determination of Negro Americans to win freedom from every form of oppression,” he proclaimed, “springs from the same profound longing for freedom that motivates oppressed peoples all over the world.” He strongly identified with anticolonial liberation movements, meeting veterans of Gandhi’s satyagraha movement in India in 1959 and traveling to Ghana for Kwame Nkrumah’s inauguration in 1960. Like many leftist figures navigating cold war politics, however, King’s criticisms of American foreign policy could often seem restrained, couched in the obligatory tropes of anticommunism or paeans to pacifism.

It was Vietnam that served as the inflection point for King’s radicalization on matters of global justice, but Joseph helps underscore Malcolm’s underappreciated influence on this shift. Malcolm was a prescient critic of the war from the outset, eviscerating its premises with a moral clarity that eluded most commentators, who were gaslighted by lies that US troops were acting as noncombatant “advisers” in Southeast Asia. “You’re not supposed to be so blind with patriotism that you can’t face reality,” Malcolm warned, charging that the war was a “criminal” act made palatable by racism and deception.

Malcolm’s antiwar critique and denunciation of the draft as “the most hypocritical governmental half-truth that has ever been invented since the world was the world” found its most important supporters among the student organizers in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the first civil rights group to dissent from the war and the draft. How, Malcolm asked, could one accept being drafted to fight on behalf of a supposed democracy, only to return home concerned about how you “can get a right to register and vote without being murdered”?

King, whose political ties to Lyndon Johnson and mainstream liberals made him more tentative in speaking out against the war, became openly critical of the administration after young activists pressed him on the hypocrisy of preaching nonviolence at home while remaining quiet about militarism abroad. Against the private advice and public chastisement of some of his closest advisers, he denounced both the war and the systemic injustices revealed or intensified by the effort to fight it. The war, he charged, represented a threat to free speech and legitimate dissent, and it bred cynicism concerning both the use of violence and the rights of nonwhite peoples for self-rule. Further, he charged the war effort with the “cruel manipulation of the poor,” lamenting its unethical waste of vital resources as well as how it sent

the black young men who had been crippled by our society…8,000 miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in Southwest Georgia and East Harlem.

In our era of perpetual warfare, with its boomerang effects on domestic liberties and civic trust, such insights remain unheeded.

The questions both men were converging on concerned the worth of citizenship in a society riven by economic domination, racial hierarchy, and belligerent militarism: What, if any, allegiance or sacrifice could such a society demand? The ideal of “radical black citizenship,” which Joseph most closely associates with King, contends that full, equal citizenship for African-Americans requires not just the formal recognition of equal rights but also the fair value of those rights. This means not only the ability to act on them as any other citizen might, but also the inability of a privileged class of citizens to unjustly enrich themselves at the expense of the least powerful.

In Why We Can’t Wait (1964), for example, King wrote that “Negroes must not only have the right to go into any establishment open to the public, but they must also be absorbed into our economic system in such a manner that they can afford to exercise that right.” As Joseph reminds us, his conception of civic equality extended to things like “a good job, living wage, decent housing, quality education, health care, and nourishment.” Or as King put it in 1967, true freedom in an affluent society cannot mean the “freedom to hunger, freedom to the winds and rains of heaven, freedom without roofs to cover [our] heads.”

In venturing into the terrain of political economy and attempting to treat Martin and Malcolm as thinkers of comparable stature, however, Joseph runs into some difficulty. It is hard to reconstruct, with clarity and consistency, Malcolm’s views in the last year of his life. Still, Joseph is probably too congenial to Malcolm’s late self-description, in which he went so far as to say that “my objective is the same as King’s,” while calling for a “black united front” of various racial justice organizations. As Joseph details, emissaries from King’s camp, including the lawyer Clarence Jones, met with Malcolm, and no less than Coretta Scott King seemed to appreciate his description of his militant rhetoric as an attempt to aid the civil rights movement. In an impromptu appearance in Selma in 1965, while Martin was jailed, Malcolm suggested to Coretta that showing white people “the alternative” might make them more willing to listen to King.

But King’s view of the world that he hoped mass protest would bring into being went far beyond Malcolm’s populist appeals to the “downtrodden masses” left behind by civil rights legislation. For King, equal civic standing, at least in an ostensible democracy, also means that each of us participates in decision-making, determining the contours of our common life together through deliberation. Indeed, one of his principal arguments concerning the evil of segregation was its assault on freedom. Segregation, King said, imposes undue “restraint on my deliberation as to what I shall do, where I shall live, how much I shall earn, the kind of tasks I shall pursue.” Segregation destroys the vital human capacity to authentically “deliberate, decide, and respond” by imposing restrictions on when and where we may enter.

If democratic citizenship is to be free and equal, it must uproot habits, power arrangements, and resource distributions that leave us subject to the arbitrary impositions of others in the most vital domains of life. As Joseph notes, such demands extended to capitalism itself and partly explain King’s skepticism toward its basis in “cut-throat competition and selfish ambition.” In 1967, for instance, he wrote that “if democracy is to have breadth of meaning,” we must overcome the “contemporary tendency in our society” to “compress our abundance into the overfed mouths of the middle and upper classes until they gag with superfluity.”

Malcolm, however, spent most of his career defending the NOI’s narrow vision of Black capitalism as “self-reliance” and portraying welfare as a white liberal ploy that created “laziness” while turning “ghettoes into steadily worse places for humans to live.” Even after breaking with Muhammad, he derided African-Americans’ lack of productive capital and business ownership in The Autobiography of Malcolm X as “the perfect parasite image—the black tick under the delusion that he is progressing because he rides on the udder of the fat, three-stomached cow that is white America.” Admittedly, Malcolm—explicitly citing King’s discussions of social democracy in Scandinavia—began by late 1964 to attack capitalism as a “vulturistic” system, but he never got far beyond such scattered broadsides. Meanwhile, King’s writings continue to inspire some of the best philosophical work on socioeconomic justice, including Tommie Shelby’s Dark Ghettos (2016), a strident defense of King’s call to abolish these zones of racial segregation and concentrated poverty.

Perhaps more tragically, Malcolm’s criticisms of so-called integrationism never adequately grappled with the leftist tenor of King’s views, which could be better described as “reconstructionist” rather than “integrationist.” For King, authentic integration was “meaningless without the mutual sharing of power.” Kingian integration would involve the widespread redistribution of assets and real democratic participation in economic and political decision-making instead of allowing municipal borders, the dictates of private profit, and existing measures of “merit” to unfairly disadvantage the life chances of so many Americans.

If Malcolm had concentrated less on diagnosing such views as rooted in psychic abjection and took more seriously the experimentalism and egalitarianism in left integrationists’ rethinking of American institutions and norms, he could have helped move the debate beyond what Stokely Carmichael later mocked as tokenistic, “one-way street” integration.2 The cost of this missed conversation lingers today. In the 2020 Democratic presidential debates, Kamala Harris assailed her future running mate, Joe Biden, for his opposition in the 1970s to federally mandated “busing” plans, but the conversation dissipated when Harris (and the broader public) evinced little enthusiasm for a debate about federal interventions to achieve school integration in the twenty-first century.

Even in the face of Donald Trump’s fearmongering calls to “protect the suburbs” from integrationist invasion, liberals focused on charges of GOP racism rather than explicitly defending the Obama-era Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule that occasioned this conservative gambit. While the left undertakes a sustained reassessment of Black intellectual history and King in particular, it has nevertheless failed to make much headway on a workable public philosophy that combines King’s “ethical demand for integration,” the “revolution in values” he called for in political economy, and the concern to promote, as King partially learned from Malcolm, the social foundations of Black dignity.

King’s question, given renewed urgency by the collapse of American education in the pandemic, is whether a tighter knitting of our “shared garment of destiny” can generate a spirit of solidarity and civic experimentation capable of resisting the opportunity-hoarding, fiscal absurdities, and simple discrimination that subject vulnerable Black children to “injustice and waste.” Malcolm’s equally significant retort is whether such programs might avoid Black humiliation and achieve participatory parity in decision-making.

The Sword and the Shield helps us find our way to such questions by transcending the exhausted divisions and glib formulations that prevent us from seizing Malcolm’s and Martin’s thought as part of our usable past. In the last year alone, American politics has been riven by a partisan nihilism that indulges the grotesque mobilization of racial paranoia about Black crime and antiracist protest, the cynical repression of Black voters, and a barbarous indifference toward the death and suffering of poor and working-class Blacks from Covid-19. The catastrophic irrationality underlying these practices raises deserved anxiety over whether there is, any longer, a path for American democratic renewal out of decadence, disease, and despair.

If there is an answer, perhaps some part of it lies along what Joseph calls the “revolutionary path” of Martin and Malcolm. They did not arrive at their destination—likely no one worth following does—but their rich archive of reflection on justice, citizenship, dignity, and dissent is a surer guide to what ails us than the poll-tested, self-satisfied advice of America’s precarious liberal elite. Revisiting these Black radical voices of the twentieth century, we retrain ourselves to glean, in the calamitous and contentious discord of the present, both the profound scale of the long-deferred reconstruction ahead and the “audacious faith,” in King’s words, that ordinary people like us would be up to the task.

—This is the second part of a two-part article. The first part may be read here.

This Issue

March 11, 2021

Spirited Away

The Truth About Museveni’s Crimes