“Maybe fear is the only emotion with which the soul wrestles constantly,” Dima Wannous writes in her second novel, The Frightened Ones, the first to be published in English. “It is dazzlingly innovative and multifarious, reinventing itself at every turn.” Suleima, a contemporary Syrian woman of about forty, is contemplating why her boyfriend, Naseem, has chosen to use a pseudonym for his books. His decision, she realizes, points to the sharpest fear of all, and one she shares: the fear of fear itself. It is “the deep current beneath my life,” Suleima reveals. “Fear of fear never leaves you.”

The Frightened Ones is told through a pair of accounts. The first is Suleima’s journal—a chronicle that, in the book, is “real”—and the second is Naseem’s unfinished manuscript, which he has sent to her from exile in Germany. The two alternating parts are distinguishable only by typeface; at times Suleima herself cannot tell the difference. (The translator, Elisabeth Jaquette, has spoken about her initial attempts to separate the book’s two voices, before realizing such a clear distinction was not in the Arabic original.) Naseem’s narrator, a woman who is never named, seems to have much in common with Suleima psychologically, if not in social background. Suleima suspects that Naseem has stolen from her life to write his novel: “It’s true that her family is different, as are her memories, but our souls clearly spin in the same orbit,” she observes, with mounting panic.

Since Naseem is absent, unable to answer the many questions she has, her worries play out in imaginary conversations with him, as well as in sessions with her therapist, Kamil. In Suleima’s imagination, Naseem asks why she believes her own experiences—her family’s flight from the massacre in Hama in the 1980s, the questioning at school about her father’s allegiance to the regime, her brother’s “disappearance” after the revolution started in 2011—are so different from those of many other Syrians. This suggestion that her story is not singular threatens her sense of self: Had Naseem, she wonders, “left [her] without an identity?” Or was it the opposite, and Naseem needed the specificity of her situation to write his novel? In Suleima’s words, “Did you borrow my life to escape your own?”

The first account of fear belongs to neither of these two women telling their stories, but to Leila, Kamil’s secretary. Suleima recounts how Leila’s brother was driven insane after being tortured by the Syrian secret police for dating a woman one of the officers’ sons liked: “They hung him from his feet for days, left him upside down, until his mind poured out, to the last drop.” Kamil’s waiting room is full of people with stories “not dissimilar” from Leila’s family’s. This becomes a central concern of The Frightened Ones: Where are the boundaries between individual and collective fears in such a traumatized society?

Suleima and Naseem first meet in Kamil’s waiting room, beginning their vexed, often incomprehensible fifteen-year relationship. On their first date, Naseem does not speak. On the second, he breaks with social convention by sitting in the back of a cab with her and holding her hand. Suleima offers scattered images of the couple’s intimacy, hugging on the couch or lying alongside each other in bed, and she describes Naseem’s panic attacks, paranoia, and self-destructive behavior in detail. Still, he remains a mystery—a cipher for her fears and a sounding board for her thoughts. “Later, I realised that I loved him best when he was silent,” Suleima says. “When I told Kamil about it, he tried to hide a triumphant smile: my distaste whenever Naseem spoke was proof that I didn’t love him as he was, but as I imagined him to be.”

How does a Syrian write about the revolution, ongoing, continually catastrophic? Naseem tells Suleima that the events were blocking his imagination; later, Suleima wonders whether he’ll ever be able to write directly about what is happening in Syria: “Maybe he couldn’t manage to write a novel about the revolution, and dealt with this weakness by composing a fictional diary instead.” Wannous, a Syrian writer born in 1982, surely intends this as a message to the reader; Suleima’s description of the form of Naseem’s novel as “a diary, written in a somewhat impressionistic and improvisatory style,” is precisely that of The Frightened Ones.

When Naseem’s narrator—who, like Naseem and Suleima, is a patient of Kamil—reports that the therapist has advised her not to keep a journal, it is unclear whom he is advising, the woman or the man in the relationship—one further example of the ambiguities that ripple out from the fiction within a fiction. Likewise, the mysterious narrator’s response, under Naseem’s pen, could belong to either lover: “He never told me not to borrow from other people. I ran away from my journal and into others’ lives. I did not tell them I wanted to escape from my own memories by stealing theirs.” There is no respite in the mind. “My imagination blazes in service of fear and anxiety, and baulks at comfort,” Naseem’s narrator says.

Advertisement

As a child, Suleima envisioned detailed scenarios of her father and brother being taken away and tortured. “Alone in my bed at night, I cried,” she remembers, “even though I knew they were nearby in their beds.” Kamil sees this as self-flagellation. And anticipating fear offered no protection: mental pictures of her father kissing the boots of an officer became, with the revolution, “no longer imaginary.” Her father winds up dying peacefully in his sleep at seventy, although, according to her resentful mother, this too was owing to fear—the nameless fear of being judged an enemy of the government, simply by being from the city of Hama, the Syrian base of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Her brother, Fouad, participates in protests against the regime and experiences the joy in freedom from fear: “I yelled and I heard my voice,” he exclaims. “Everyone was shouting and clapping…. The age of silence is over!” But soon he is arrested and becomes one of the disappeared, for which Suleima berates herself further. She prays for his death constantly, thinking it better than the torture she has already imagined. Naseem, for his part, practices literal self-flagellation: when he can’t express himself to Suleima, she hears him hitting himself during their phone conversations: “I’d known from the start that our call would end with a slap.”

Naseem writes obituaries for those he loves, even before the formality of their deaths: “There wasn’t anyone in his family he didn’t kill with words, describe their funeral and come to terms with losing, again and again and again.” (Discovering her own obituary in Naseem’s apartment in Syria is a new source of terror for Suleima, who buries the paper, then has nightmares of being buried herself.) For Naseem, this is an attempt to exercise control: “He wanted to decide when the fear would strike him, rather than let it do so when he least expected.”

Naseem’s and Suleima’s terrible thoughts are not only forms of self-preservation. One of the most notable features of The Frightened Ones is its tenderness, both narrators showing the love—of family, of partner, of country—at the root of so much fear. Jaquette, the translator, has explained that it was precisely this mixture of an “intimate, personal perspective” in a book that “[grappled] with large, nationwide, global events” that first drew her in. This tone of intimacy makes Wannous’s novel different from other contemporary Syrian literature, such as Zakariya Tamir’s short stories—sharp, sometimes folkloric explorations of the country’s sectarianism, patriarchy, and economic oppression—or Mustafa Khalifa’s unflinching The Shell, a fictional account of the author’s brutal thirteen-year experience in an Assad prison, or Khaled Khalifa’s Death Is Hard Work, a finalist for the 2019 National Book Award. The latter is also set during the Syrian revolution and contains the same horror and fear that Wannous explores.

“Fear had become the only true opposition; it was now each individual versus their own fear,” Khalifa writes. His novel depicts three siblings attempting to transport their father’s body through the complex landscape of civil conflict, one checkpoint at a time. Over the many days it takes to reach the father’s village, a journey that in normal times might take five hours, the body begins to putrefy. Some scenes show dark humor, but the overriding impression of this dystopic experience is abrasive, the cracks observed so starkly in the civil war mirrored in the distrust and antagonisms within one family.

Wannous’s characters also travel within Syria, and across its different worlds. Suleima’s family flees from Hama, in the north, south to Damascus, the capital, after the 1982 massacre in which the government brutally suppressed the Muslim Brotherhood, killing up to 20,000 civilians in the process. Naseem’s narrator straddles a fault line with an Alawite father, from the coast of the Mediterranean, and a Sunni, Damascene mother. (The Assad family that rules the Sunni-majority country is from the minority Alawite sect.) Naseem himself is from Homs, a city besieged and destroyed early in the revolution.

Elements of Wannous’s life also make their way into those of her characters. She was raised in Damascus and her father worked in the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts, as does Suleima’s brother, Fouad. Then there is Wannous’s father’s death when she was a teenager, and her own exile in Beirut. In interviews, Wannous has denied the autobiographical element of the novel, but the work may explain the parallels more accurately. Afraid that her story is being stolen by Naseem, Suleima imagines him rebutting her accusations with an appeal to shared experience: that as Syrians, “we all have the same story…one aching version of humankind.”

Advertisement

Naseem’s narrator has family in Tartus, on the coast; during her trips there with her father, she appreciates the gradual greening from interior desert to the strip of fertile land before the sea. She is met by the love of a grandmother and the constant scolding of a grandfather and aunt: “Their chastisement was born of a complex relationship between the countryside, where they lived, and the capital, Damascus, where we did.” But the splits between her Tartus family and her family at home in Damascus are about more than rural and urban life; they also concern “my father and his Sunni Damascene wife, the woman who had stolen him and stolen me too!” This sectarianism is not about belief but about community, place, origin. The narrator is relentlessly teased for her brown skin and eyes and gets cruelly taunted as “darkie.” Her coastal cousins are fair with blue eyes, and they work hard to retain this complexion; they are “mad about staying white,” keeping out of the sun and buying whitening creams laced with mercury. These relatives emphasize her difference, and also their claim on her: “I was given freedom from every rule…in unspoken defiance of my mother.”

With Naseem’s narrator’s return to the capital each autumn, we observe the divisions in Syria more sharply. Every summer she acquires the Alawite accent, a difference explained over a few pages in an extraordinary feat of translation. (The comments on society and class that are self-evident to an Arab, especially Syrian, audience, are made comprehensible to Western readers through Jaquette’s considerable ingenuity in the choice of examples of speech patterns.) It begins with an incident when the narrator is six or seven and, dressed prettily, is taken to a jeweler’s shop, the shopkeeper calling her a “princess.” Then she asks for some water and the shopkeeper is stunned, looking around for the source of the request, unable to process that this “princess” might speak like an unsophisticated Alawite, a “country bumpkin”: “The accent signalled a history’s worth of stereotypes and the suffering of millions; dialect alone was enough to unleash its savagery.”

Memories like these pile up to underline what we already know: this woman’s Alawite family turns on her when the revolution begins. The uprising itself is introduced with a shocking letter from a cousin she had spent childhood vacations with: “‘I don’t hope they kill your mother, oh no,’ she wrote. ‘I hope they rape you in front of her, and then slaughter you like an animal, so she spends the rest of her days in agony.’” Naseem’s narrator wonders about the rift: “Was it possible for someone to go to sleep as a human being one night and wake up a vicious beast? Or had the beast simply been hiding, lurking in the body of a woman so educated, loving and refined?”

This, then, is how Naseem tackles the revolution: the stories of how underlying tensions surfaced as hatred; the snide comments about his narrator’s Damascene mother in childhood transformed into vile threats (the hope that “the Sunni womb that bore you rots with cancer”); families falling apart, relationships destroyed.

The revolution erupted in an instant. And in that instant, monsters appeared. They filled our city, our homes, our living rooms. They hit and slapped and insulted and killed and destroyed a whole history of human relationships.

Hidden monsters are also present in Suleima’s portion of the novel, though not within the family structure. The Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts had hitherto been a refuge for Fouad: “He loved the atmosphere, his students and the geographic and sectarian diversity that had somewhat escaped the regime and security services’ grip.” But the nonsectarian atmosphere did not survive: “After the revolution began, that elegant white building coughed up its soul and was possessed by another one.” Security services arrived; people, including Fouad, disappeared. “Divisions emerged”—emerged, not formed. Wannous shows that the structures and methods of the Assad regime laid the groundwork for both the revolution and its undoing.

Naseem’s manuscript has the most succinct description of this groundwork, using his narrator’s school as a microcosm of society. School was where “students experimented with ways of life they might later lead in Assad’s Syria. A place to train, to learn to cast silent insults and be drilled on obeying the powerful and respecting the authoritative.” At each level of the hierarchy there is mistrust and hatred of those under it: “The headmistress hated the teachers, the teachers hated each other and the students, and the students hated each other in turn.”

There is a school in Suleima’s story, too. When she is in year ten (fifteen to sixteen years old), Suleima is called into a teacher’s office and asked about Hama: “Has your father told you what happened there?” The fear is total; she not only feels it on behalf of her father, but transforms into him: “Immediately my stomach cramped, the way yours would have done if you had been there. I won’t forget how weak my knees became, how fragile I felt, oh Baba.” Suleima replies as any well-drilled child of Assad would have: “Our Father the Leader has bloodied his hands for the entire Syrian people.” A perfect, learned response. But all she gets in return is a smile, no resolution of punishment or praise, thus prolonging the terror. “Here, I’m speaking again about fear of fear,” the adult Suleima reflects. A universal state for Syrians, a threat unmistakable even to a schoolchild. “Anticipating fear is harder than feeling it,” she says. “Prison is easier than fearing it. Fear on its own is less cruel than fearing fear.”

Suleima writes to Naseem in diary entries and unsent letters, and to her late father, both men equally unreachable. She has stayed in Damascus, unable to leave her mother and the chance of recovering her brother, dead or alive, from Assad’s prisons. She tells Naseem what the revolution feels like, again slantwise, describing neither the violence of battles and torture nor the politics nor foreign intervention, but her account is just as revealing. “The revolution ended the day you and everyone else left,” she tells him, in another letter added to the pile unsent. “Revolutions don’t come from books, Naseem, they don’t spring from words on the page. Revolution means begging my mother not to fall ill, every morning and night.” She goes into the third person to explain why she cannot tell him about such daily exhaustions, before going back to direct address: “He would have found it difficult to handle life in this terrible city…. You have to choose when your health will fail you, Naseem.” The constant shifting between first-person memories, second-person addresses, and the imagined experiences of others demonstrates the intense loneliness of this intensely loving person.

Suleima’s own unraveling, with silence from Naseem the only response to her text messages, is partially fueled by jealousy, a suspicion that Naseem wasn’t stealing from her life, but that of another lover. In searching his abandoned apartment, she finds a stack of photos of women, and in an echo of the novel itself, she cuts them up to make a collage of watchful, silent, disembodied eyes.

Kamil’s office prompts the novel’s final slip between individual and collective experience. Suleima sees his waiting room fill with Assad’s thugs, the shabiha, and addresses Naseem directly again: “I wonder how Kamil can treat shabiha and murderers,” she writes. “Men with inflated muscles and broad shoulders, their expressions tinged with evil and fear. Have you ever seen evil coexist with fear?” She wonders whether any of them have Fouad’s scent on their hands.

In a therapy session, Suleima notices Kamil’s own exhaustion; it dawns on her that Kamil, too, “was experiencing the same thing we were: we the crushed, unnerved and frightened ones.” There had once been a clear delineation between patient and doctor, but “the revolution had snapped that line,” she writes. Now Kamil, supposedly the source of strength and perspective in a therapist’s chair, has joined the frightened ones.

The book ends without resolution. In the final pages, Suleima finds herself thinking not of her father, or of Naseem, but of her mother, the only person who is present with her, who can offer comfort and “absorb the emptiness I felt when these men to whom I had belonged were gone.” Suleima’s nightmares continue, but when she wakes her mother asks, with a smile, “Coffee, sweetheart? It’s hot.”

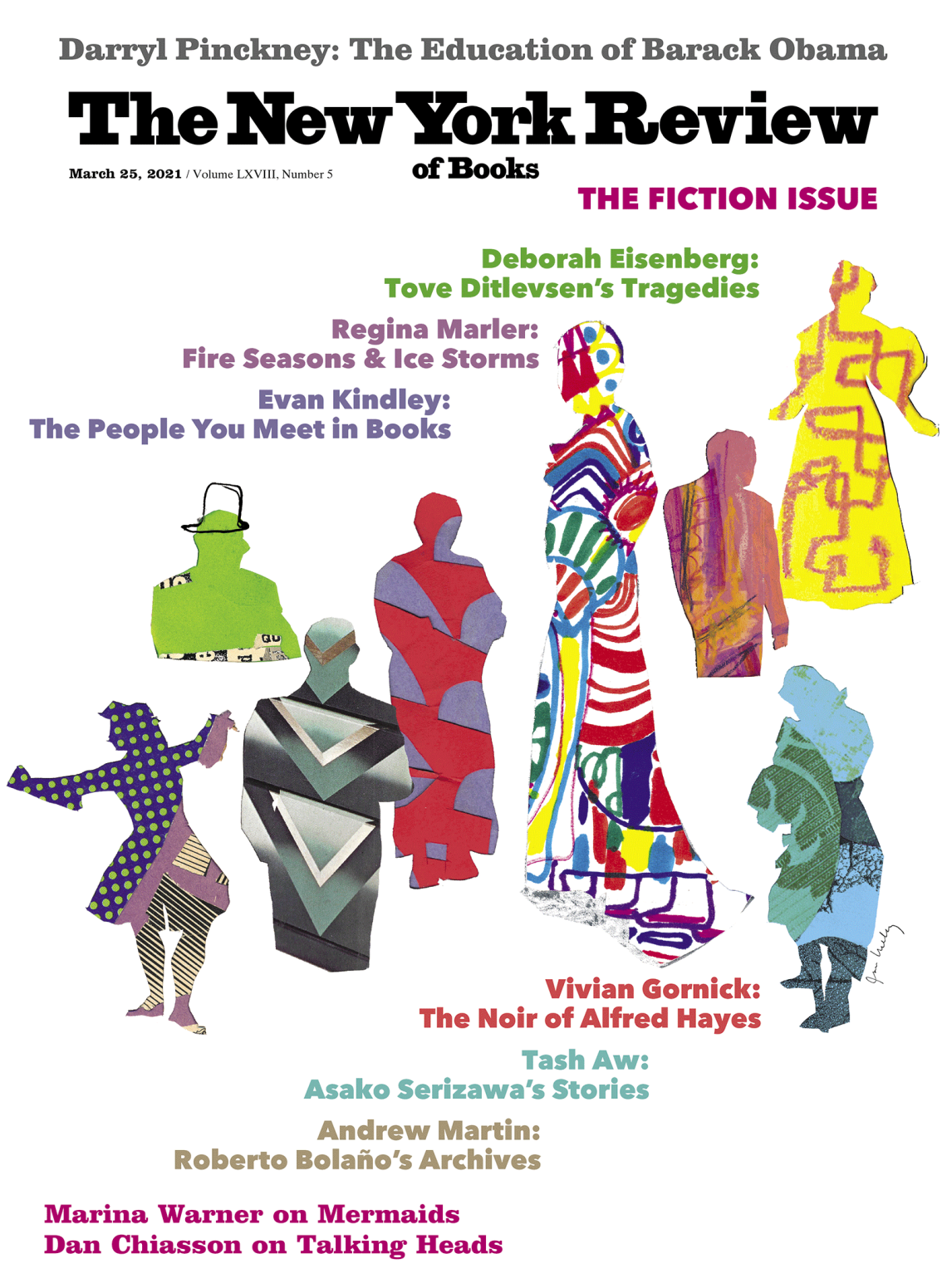

This Issue

March 25, 2021

A Gift for the Long Game

Splash

The Emergency Everywhere