In response to:

‘A Very Lonely Business’ from the February 11, 2021 issue

To the Editors:

In her wonderfully affecting discussion of women writers and their relation to being, or to not being, mothers, Daphne Merkin writes that “tackling the chores of motherhood while also trying to find the time and concentration to write or sculpt or paint is a supreme juggling act” [“‘A Very Lonely Business,’” NYR, February 11]. About “the decision to become a mother while pursuing a career as a writer or artist” she quotes Virginia Woolf: “How any woman with a family ever put pen to paper I cannot fathom.”

As a man who was single parent to his three children while pursuing a career as a writer, I can vouch. When I was in my early forties (in the 1980s), my wife and the mother of our three children left me and our children. And so, like many women, I didn’t make a “decision” to raise my children while pursuing my career as a writer, but had the decision made for me. Consider—one example among many—the career of Penelope Fitzgerald, who published all nine of her novels, and all but one of her books of nonfiction, only when, after her husband’s death, and without any financial wherewithal, she became the sole parent to their three children. That Fitzgerald did not write her novels until her children were grown may (or may not) reinforce Merkin’s assertion that

the matter of motherhood and artistic creativity remains an either/or question, a deeply conflicted issue even now, despite the fact that the advances of feminism have helped women pursue occupations and goals that were once out of grasp. It is as though we have not yet reconciled ourselves to the idea that the one generative desire need not necessarily preclude the other—that we can, within reasonable bounds, have it all, even if imperfectly, which creative men have pretty much taken for granted right along. [italics added]

Point well taken. Though there were many days when I kept telling myself, “Today you’re not a writer—you’re a parent…Today you’re not a writer—you’re a parent,” and though for many years my youngest son would, on the second Sunday in May, even when he was away in college, wish me a happy Mother’s Day, it occurs to me that I was able to juggle the competing demands of writing and parenting not because I drew on some latent womanly/maternal instincts, but because I was a man—because my life as a twentieth-century American man had given me a particular and large sense of entitlement, a habit of believing and acting on the belief that I could have and do anything I wanted if I wanted it enough and worked hard enough to get it. So, yes, I did take it for granted that, “within reasonable bounds,” I could “have it all.” And having it all meant I could continue in my career as a writer while also continuing to raise my children, though now—what proved to be the great good fortune of my life—doing so on my own, thereby gaining a small measure of understanding about what women’s lives, like Merkin’s and the women she writes about, are often like.

Jay Neugeboren

New York City

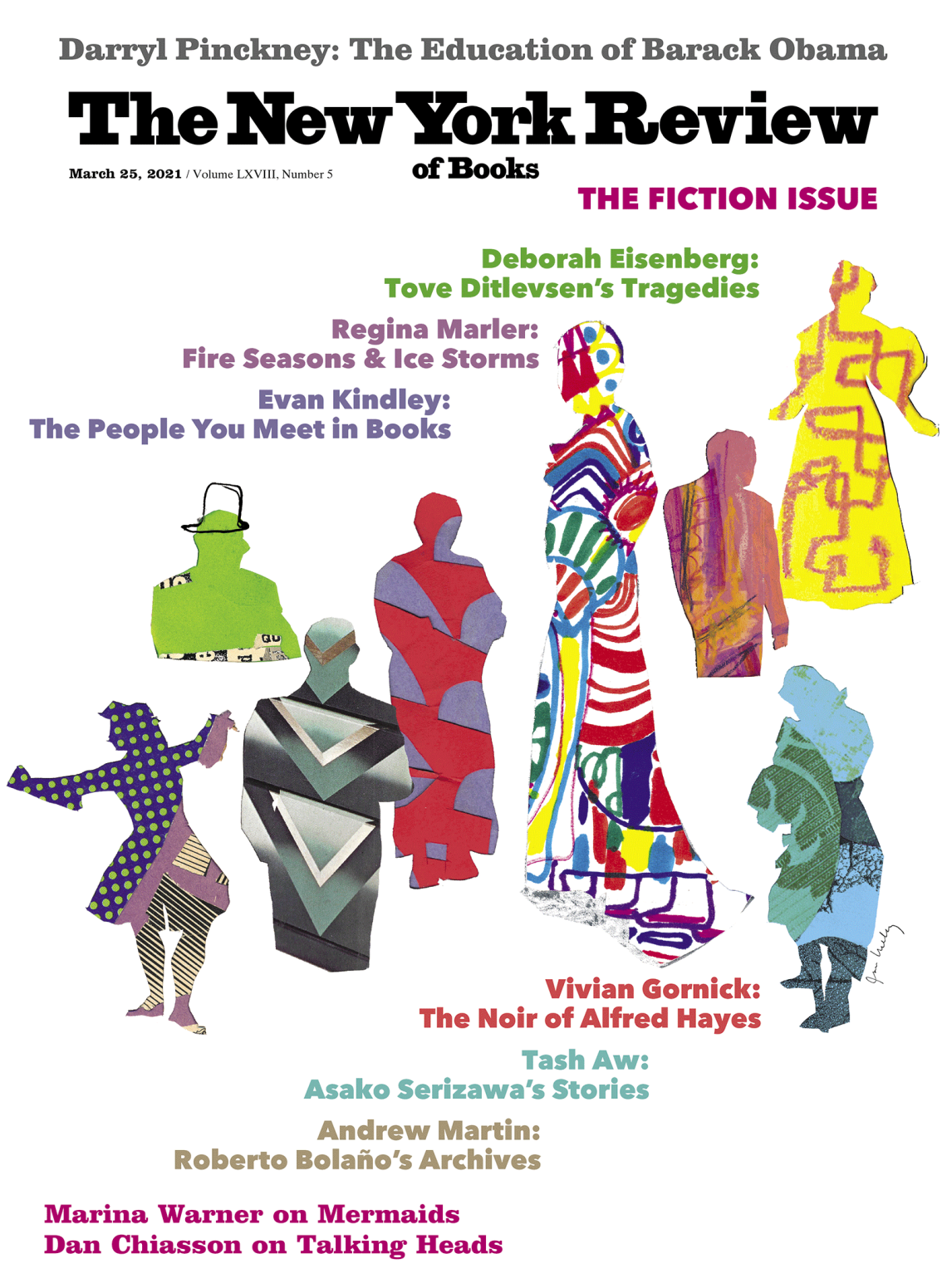

This Issue

March 25, 2021

A Gift for the Long Game

Splash

The Emergency Everywhere