The appearance of a new English translation of Ernst Cassirer’s The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms marks the culmination of an unlikely intellectual revival. Cassirer’s three-volume magnum opus, first published in Germany between 1923 and 1929, was translated into English by Ralph Manheim in the 1950s, when its author’s reputation was in decline. For a long time thereafter, it didn’t seem the book would ever need retranslating. Interwar German thought exercised an enormous influence in the late-twentieth-century US, from Martin Heidegger’s existentialism to the critical theory of the Frankfurt School to the Marxist mysticism of Walter Benjamin. But the apocalyptic radicalism that made these thinkers so fascinating—the product of a period that felt like, and in a sense really was, the end of the world—is absent in Cassirer.

Instead, The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms focuses unfashionably on the power and progress of the human mind. Drawing on an exceptionally wide range of sources—in linguistics, anthropology, religion, psychology, math, and physics, as well as philosophy—Cassirer argues that the classic Aristotelian definition of the human being as a rational animal is wrong, or at least incomplete. Instead we should think of ourselves as “symbolic animals,” since ratiocination is only one expression of the human instinct to think in symbols.

Art, myth, and language are also forms of thinking, Cassirer insists, just as much as philosophy and science. “Each of them creates its own symbolic configurations, which if not of the same kind…are, nevertheless, equal as to their spiritual origin,” he writes in the introduction to the first volume. “None of these configurations can simply be reduced to, or derived from, the others; rather, each of them…constitutes its own aspect of the ‘actual.’”

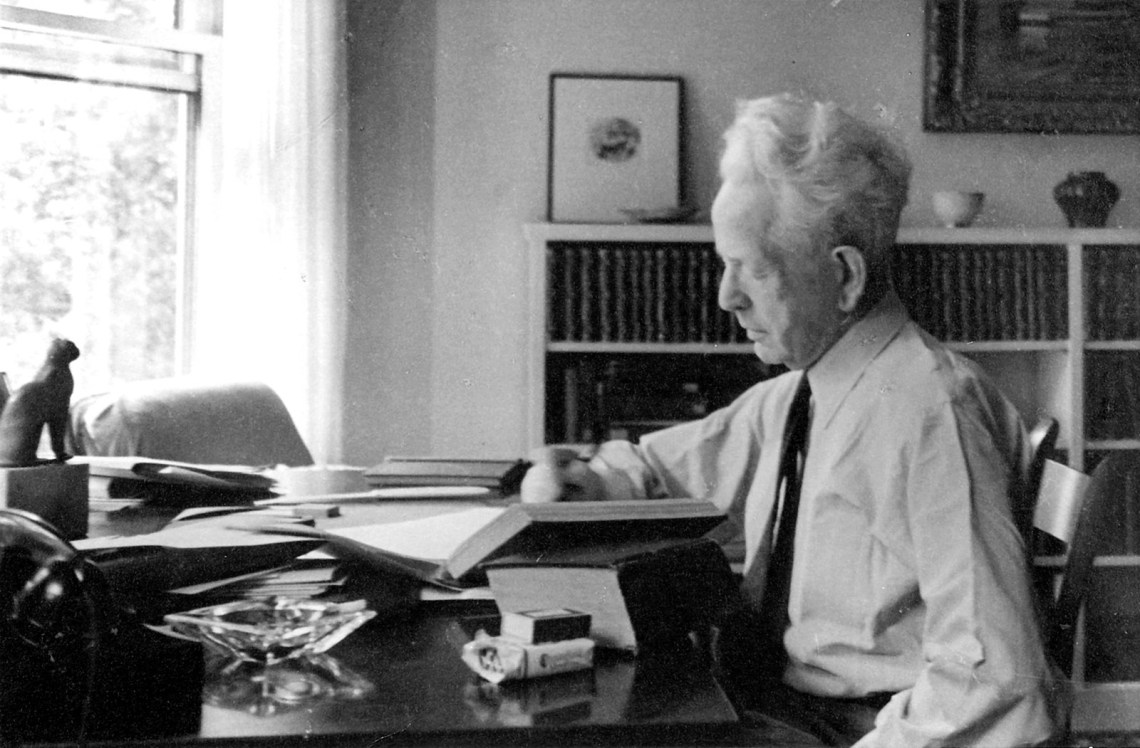

The three volumes of The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms focus on language, myth, and science respectively, offering fascinating, if necessarily fragmentary and speculative, accounts of how each develops in the direction of increasing freedom and universality. This essentially affirmative view was “out of tune with its time,” as Peter E. Gordon writes in his preface to the new edition. Yet Cassirer knew the darkness of the time as well as anyone. Born in 1874, he became a leading figure in German philosophy before World War I, though his Jewishness kept him from being appointed to a professorial chair until 1919. But his academic career was cut short in 1933, when the Nazis, as one of their first acts, prohibited Jews from teaching in universities.

Cassirer and his wife quickly fled the country, and he spent the next dozen years as an émigré, moving from post to post in England, Sweden, and finally the US. He was teaching at Columbia when he died of a heart attack on the street near 116th and Broadway in April 1945, one day after FDR. Cassirer was laid to rest in a Jewish cemetery in Paramus, New Jersey—a destination the German mandarin could never have imagined.

His work found some admirers in this country, most notably Susanne K. Langer, whose Philosophy in a New Key (1941) built on his idea of art and myth as nonsemantic forms of thought. By the turn of the century, however, Cassirer had almost vanished from the consciousness of the American intellectual public—especially compared with Heidegger, who became ever more fascinating as his history of Nazi involvement came into clearer view.

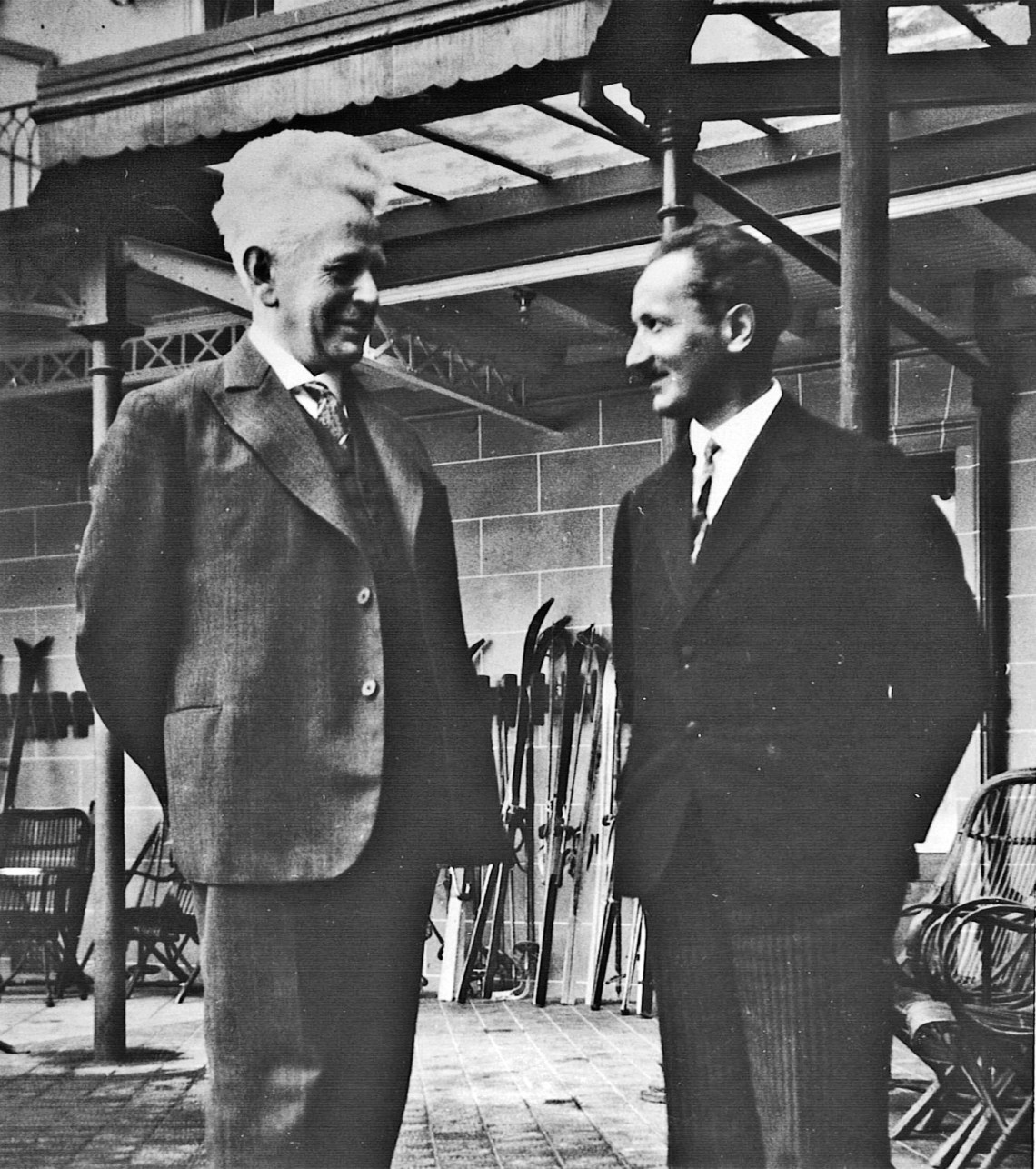

Then, in the 2000s, the tide began to turn. In Ernst Cassirer: The Last Philosopher of Culture (2008), Edward Skidelsky wrote semi-ironically of the “Cassirer industry” that had already sprung up in Germany. Skidelsky’s book was followed in English by Gordon’s magisterial Continental Divide (2010), a detailed analysis of a storied 1929 debate between Cassirer and Heidegger in Davos, Switzerland. In 2013 Emily J. Levine’s Dreamland of Humanists proposed that the Frankfurt School had a rival in a “Hamburg School” centered on Cassirer and Erwin Panofsky, both of whom did research in that city’s Warburg Library.

The renewed interest in Cassirer has led to new editions and translations of his work, including several by Steve Lofts, who has now translated The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms. It has even begun to trickle down into popular intellectual history. Wolfram Eilenberger’s Time of the Magicians (2018), a best seller in Germany that appeared in English last year, is a fast-paced group portrait of four thinkers who “reinvented philosophy” in the 1920s: Heidegger, Benjamin, Cassirer, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. It’s safe to say that a similar book written twenty years ago would not have included Cassirer in that company.

Yet even the scholars who helped revive interest in Cassirer can be reticent about making claims for his achievement. In his preface, Gordon warns that “certain features of Cassirer’s work have grown antiquated and unpersuasive,” particularly his belief in cultural progress, which is “altogether intolerable.” Skidelsky writes that he began his book intending to make “a plea for Cassirer’s continuing importance, a protest against decades of neglect,” but that as he delved deeper he realized that “the problems facing Cassirer’s enterprise were far more serious than I had initially supposed.” He even speculates that the roots of the Cassirer revival are “more political than philosophical,” particularly in Germany, which is “in desperate need of figureheads who are cosmopolitan in outlook yet distinctively German in intellectual style. Cassirer fits the bill perfectly. That he was Jewish and an enemy of Heidegger also helps.”

Advertisement

The last point is particularly ironic, because it was Heidegger who struck the first blow against Cassirer’s standing as a major thinker. Hardly any account of Cassirer fails to mention their Davos debate; it is a high point of Eilenberger’s book, where it’s described very much in the style of a boxing match. (“Body blows. Heidegger was now cornered.”) Beyond the philosophical issues, the debate is biographically significant because of how starkly the two men’s fates diverged a few years later.

In April 1933, the same month that Cassirer was stripped of his professorship at the University of Hamburg, Heidegger was appointed rector of the University of Freiburg, tasked with bringing it into alignment with Nazi principles. An enthusiastic supporter of Nazism, whose “inner truth and greatness” he lauded, Heidegger presided over the purge of Freiburg’s Jewish faculty, including his principal mentor, the philosopher Edmund Husserl. In light of this history, the fact that Heidegger was widely seen to have won the debate at Davos raises important questions. If Heidegger the Nazi is a more profound and significant thinker than Cassirer, who was a prominent defender of the Weimar Republic, what does that tell us about the relationship between philosophy and politics, between profundity and morality?

As Gordon shows in Continental Divide—which includes a full transcript of the debate—the Davos encounter focused on the proper interpretation of Kant, not an obviously dramatic subject. But to the young people in the audience, it was clear that what was really at stake was the fate of an intellectual generation. Otto Friedrich Bollnow, a student of Heidegger’s who helped transcribe the speakers’ remarks, recalled years later:

One sensed the encounter between two ages: one, an inheritance that had come to its ripe unfolding, was embodied in Cassirer’s imposing form, and, over and against him, the embodiment in Heidegger of a new time, breaking out with the consciousness of a radically new beginning.

The antagonists were well cast. Cassirer, fifty-four, was at the height of his authority as an interpreter of science and culture in the Kantian tradition; he would publish the concluding volume of The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms later that year. Heidegger, thirty-nine, was already established as the leader of the postwar generation, thanks to the pioneering existentialism of his book Being and Time (1927). Bringing the two together was intended to strike sparks. The International Davos Conference, an academic colloquium designed to foster international dialogue after World War I, was only in its second year, and its organizers hoped the Cassirer-Heidegger debate would help them repeat the success of the inaugural meeting, when Albert Einstein was the headliner.

The intellectual difference between the two men was compounded by the social, political, and even physical contrasts. Cassirer—tall, white-haired, and patrician-looking, the product of an affluent and culturally prominent family—was a perfect standard-bearer for the philosophical establishment. But the students in the audience responded much more to the combative charisma of Heidegger, who grew up poor in a rural Catholic family and liked to present himself as a man of nature rather than culture. At Davos, Gordon writes, Heidegger made time to go skiing; he enjoyed causing a sensation by showing up in the hotel lobby in a ski suit instead of evening wear.

Intellectually, Cassirer exemplified the German Jewish embrace of Bildung—moral and cultural education. The heroes of German humanism were touchstones of his thinking—Kant, Goethe, Humboldt. He was immensely erudite, in literature and science as well as philosophy, and wrote about everything from Zoroastrianism to Renaissance mysticism to Einstein’s theory of relativity. The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms rests on the idea that the history of culture offers the best way to grasp the essential freedom and creativity of the human spirit.

For Heidegger, on the other hand, it was necessary to master the Western intellectual tradition primarily in order to throw off its dead hand. His thinking aimed at recovering a more primal and authentic sense of being, which he thought had been buried under 2,500 years of philosophical rationalism. As he wrote in Being and Time:

Taking the question of Being as our clue, we are to destroy the traditional content of ancient ontology until we arrive at those primordial experiences in which we achieved our first ways of determining the nature of Being.

Cassirer and Heidegger’s clash over the interpretation of Kant exposed this profound difference in temperament and worldview. For Cassirer, the Kantian idea that the human mind creates its own world through the use of symbols was an essentially hopeful one. At Davos, he argued that this creativity is what allows human beings to achieve a kind of transcendence: “The spiritual realm is not…metaphysical…; the true spiritual realm is just the spiritual world created from [man] himself. That he could create it is the seal of his infinitude.”

Advertisement

To Heidegger, this sounded like the kind of complacent humanism he despised. If there was anything his thought insisted on, it was human finitude—the way our experience of the world is defined by mortality, anxiety, and nullity. “It is only possible for me to understand Being if I understand the Nothing or anxiety,” he argued at Davos. Skating close to open insult, he contrasted “the lazy outlook of a man who merely uses the works of the spirit” with the genuine philosopher, who is intent on “throwing man back into the hardness of his fate.”

According to the transcript, at one point in the debate a member of the audience intervened to observe that “both men speak a completely different language.” Reading The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms alongside Being and Time shows the truth of the remark. Cassirer and Heidegger think about some of the same problems, but they have very different ideas about what thinking means and sounds like.

Both books are formidably complex, but Heidegger offers a shock of recognition that Cassirer does not, because even his abstractions are rooted in concrete, familiar experiences. He analyzes the philosophical meanings of things like using a hammer, reading a newspaper, or feeling anxious. The difference is perfectly illustrated by the two thinkers’ approaches to the theory of signs, a central topic for both. In the first volume of The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms, the section “The General Function of Signs” discusses ideas on the subject from Galileo, Leibniz, Humboldt, Goethe, Kant, and the physicist Heinrich Hertz. In Being and Time, the section “Reference and Signs” analyzes the function of a car’s turn signal:

Motor cars are sometimes fitted up with an adjustable red arrow, whose position indicates the direction the vehicle will take—at an intersection, for instance. The position of the arrow is controlled by the driver.

This was written in the mid-1920s, when the automobile was roughly as new as cell phones are today. Cassirer knew far more than Heidegger about the era’s cutting-edge science, such as relativity and quantum mechanics, but Heidegger gives a better sense of living in and thinking about the contemporary world. This is the power of existentialism, which insists that our own lived experience is the necessary starting point for thinking about ethics and metaphysics.

Cassirer’s thought belonged to another tradition: neo-Kantianism, the school that had dominated academic philosophy in Germany since the 1870s. The neo-Kantians sought to reinterpret Kant’s ideas about knowledge and reality in light of new developments in science, and Cassirer’s early work contributed to this project. In Substance and Function (1910), he argued that modern mathematics and physics, with their highly abstract and unintuitive methods, give a new dimension to the Kantian idea that our minds don’t simply make pictures of things that already exist “out there.” Rather, we construct reality by understanding it in progressively more complex ways.

In The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms, Cassirer extends this project to include culture as well as the sciences. Looking back through history and into the prehistoric past, Cassirer argues that language and myth, too, develop in the direction of ever-greater abstraction and universality. As forms of symbolic thinking, they demonstrate that “in every attentive glance into the world, we are theorizing.”

As one would expect from a trilogy of books written over a decade, The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms isn’t tightly constructed; it’s less the unfolding of a system than a series of observations and arguments. Much of the book is devoted to an exposition of the findings of various linguists, anthropologists, and psychologists, few of them remembered today. Indeed, because so much of Cassirer’s analysis depends on then-current research—on everything from agglutinative grammar to indigenous religious rites to the causes of aphasia—it is vulnerable to obsolescence to a degree that’s unusual for philosophy.

But the basic insight of The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms is one that continues to inform the humanities today. The categories we use to understand the world aren’t a passive reflection of the way things really are; rather, we actively create systems of meaning that evolve over time. As Cassirer puts it in the second volume:

Objects are not “given” to consciousness in a rigid, finished state, nakedly in themselves but…the relation of representation to the object presupposes an independent, spontaneous act of consciousness.

Cassirer’s symbolic forms can be seen as a precursor to Michel Foucault’s discourses and epistemes—ways of organizing knowledge that shape what we believe and how we act. (Gordon observes in his preface that Foucault was “quite familiar” with Cassirer’s work.)

The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms is most interesting and rewarding when Cassirer engages in his own archaeology of knowledge, trying to imagine his way into systems of thought that now appear hopelessly strange. What does it mean, for instance, when a language has no single vocabulary for counting but uses different terms depending on the kind of objects being counted? This is the case, Cassirer writes, with the “language of the Fiji Islands,” which uses different words to designate ten canoes, ten fish, or ten coconuts. Why did the Roman augurs believe they could tell the future by observing which quadrant of the sky a bird flew into? In what sense should we understand the Rigveda, the ancient Hindu scripture, when it says that the cosmos was made from a dismembered human form?

A simple response would be to dismiss these as the errors and superstitions of humankind’s infancy. But “cognition does not master myth by exiling it beyond its borders,” Cassirer writes. Such symbolic forms are worthy of serious attention because they are active constructions of the mind, no less than, say, Protestantism or quantum mechanics. At the same time, Cassirer is no relativist. Early symbolic forms—and, like most Europeans of his time, he tends to think of ancient Babylonians and “natural peoples” in the twentieth century as similarly “early”—are important because they show the human mind slowly winning its way from confusion to clarity.

Over the course of the three volumes, Cassirer develops an account of that process. At the dawn of human consciousness, he proposes, concepts that appear fundamental and inescapable to us were still unknown. People had no firm sense that physical objects are located in uniform, three-dimensional space. They didn’t think of time as a line extending backward into the past and forward into the future. They didn’t distinguish clearly between subject and object, what happens “in here” and “out there.” Similarly blurred were distinctions such as part and whole, cause and effect, alive and dead. Without such categories to structure the world, human experience formed a single, overwhelming whole, a stream or flood of feelings and impressions.

Yet as far back as we can see into the history of consciousness, human beings have made efforts to master this flood by imposing form and structure on experience. A crucial term in The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms is “cut” or “incision”: symbolic thinking often involves cutting the undifferentiated world into comprehensible parts. Cassirer borrows the image from Plato, who wrote in the Phaedrus about the art of dividing ideas into natural classes by cutting them “at the joints,” like a skillful butcher.

What makes Cassirer a distinctively twentieth-century thinker is his belief that the world offers no such joints to cut along. The only divisions that exist are the ones we impose, and we can choose to make them in any number of ways. For Cassirer, linguistic diversity is evidence of this freedom, since he believes (as most linguists since Noam Chomsky have not) that differences between languages reflect different experiences of the world.

One of Cassirer’s most important examples is counting. He observes that some African and Australian languages have numbers for one and two but refer to all higher quantities simply as “many.” In Semitic languages, “the numerals [Zahlwort] for one and two are adjectives, whereas the rest [of the numbers] are abstract nouns.” Modern Indo-European languages have a singular and a plural, but ancient Greek and Sanskrit also had a “dual” number for nouns and adjectives, used for pairs of things or people.

Cassirer sees these linguistic traces as evidence that human beings developed counting not to enumerate objects but to express a distinction between selves. The first symbolic cut was the one between “I” and “you,” recognizing that people have separate minds. After this division was secured in language by the numbers one and two, it took a further conceptual leap to refer to “he” or “she”—the third person, for which the number three was required. Counting “detaches only gradually” from this subjective basis, Cassirer writes, which explains “the particular role played by the number three in the language and thinking of all peoples.”

Only with the appearance of number four and beyond does language move from designating people to counting objects, which requires an indefinite series of numbers and thus opens up the possibility of real mathematical thinking. Counting thus offers Cassirer a perfect example of the mind’s movement from the immediate, tangible, and subjective to the abstract, conceptual, and objective, which is the trajectory of all symbolic forms.

A similar progress can be traced in the world of myth. To early human beings, places, objects, and animals appear “expressive,” with values and intentions of their own. That’s why they must be fought with magical rites or appeased with sacrifices. Polytheism marks a step forward from this early mythical stage, as the personalities that once belonged to things are now transferred to the gods who watch over them—the god of the sea, the god of the sun, and so on. But the gods of polytheism are still understood as beings similar to us, with bodies and desires, like the quarreling deities of the Iliad.

The crucial incision in this realm was made by Greek philosophy and biblical monotheism, which transformed God from a personality into an ethical and metaphysical principle. Cassirer refers several times to the myth of Er in book ten of Plato’s Republic, in which the soul awaiting reincarnation is told by the Fates that its destiny is in its own hands:

Your daemon or guardian spirit will not be assigned to you by lot; you will choose him…. Virtue knows no master; each will possess it to a greater or less degree, depending on whether he values or disdains it. The responsibility lies with the one who makes the choice; the god has none.

In these lines, we can see the mythic idea of fate being transformed into the religious idea of free will and ethical responsibility.

For Cassirer, this change is parallel to the transformation of counting into mathematics, and of naming into language. But the mind’s trajectory toward abstraction doesn’t look like progress to every observer. For Heidegger, the original sin of philosophy is precisely what Cassirer regards as its greatest achievement: replacing humanity’s primal, numinous sense of Being with an objective, calculating rationalism. In his essay “The Question Concerning Technology,” Heidegger argues that this way of thinking, which he calls Gestell or “enframing,” “endangers man in his relationship to himself and to everything that is.”

This is the real Cassirer-Heidegger debate, and it goes far beyond what they discussed at Davos. Is free reason the highest human accomplishment or the source of nihilism and alienation? Do we want thought and culture to keep progressing in the same direction, or to turn back toward their origins? These questions continue to divide us in the most fateful ways; today as in the 1920s, they aren’t just philosophical but political. Perhaps the most timely insight of The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms is that earlier strata of symbolic thought never fully disappear; even in a scientific age, people are prone to magical, mythical thinking. As Cassirer writes, “Science arrives at its own form only by expelling every mythical and metaphysical component from itself.” But “the battle, which theoretical cognition believes it has won for good, will continually break out anew.”