When I was a little boy, not more than ten or eleven, I would label photographs. In our apartment in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn—I lived there with my mother, an older sister, and my little brother—photographs were kept in boxes or in albums, in which after a while the thick paper they had been affixed to would tear or, if touched, start to crumble altogether. I was always afraid of losing the photographs we had managed to save, because that would mean losing memories—memories of things that, more often than not, I was too young to have lived with the people in them.

But what did that matter? I wanted to love people and their stories, because everyone had a story: photographs told us that. And so did the eventual subjects of photographs. This I knew because my mother listened to so many of them, on the phone and in her small kitchen, where pots steamed and sometimes hissed as Mr. X or Ms. Y sat at the dining table with the Formica top, talking and talking, pleased to be—at last!—seen and heard.

In the living room, I handled photographs very carefully. I thought that if a snapshot of a woman prettily poised in black and white on some front porch, for example, were treated less gingerly, then she herself was being carelessly handled. I wanted the world to be as cared for as I cared for those photographs.

But even then I knew that wasn’t possible, that it wasn’t a “true” wish. Because underneath it all—underneath all that beautiful, anguished desire for my mother’s attention, free of other children and the constant guests—I was aware that care and tenderness didn’t always win out. Indeed, by the time I sat in that living room, slightly grossed out when the paper crumbled in my hand, I knew that the world didn’t necessarily honor, let alone pay much attention to, gentleness. Even then I knew that the world was a largely unsteady place, unreliable, threatening, untrue. Relatives lied. People left. And other kids could shut you out of their group whenever they wanted.

What, then, could one hold on to? The ephemeral. Photographed moments that confirmed or offered evidence of a collective reality—Here we are on the beach! Look what we did this summer!—and that bore witness to the fact that one had survived, and maybe had been loved, and was a memory that someone wanted to behold, or treasure, like a photograph.

For me, then, photographs bore witness to those passing moments—that fleeting smile, the birthday candles just blown out—that I longed to feel all the time, moments of joy when the photographer connected to the subject right before the camera’s eye. Pictures frame time. Pictures connect the photographer and the subject to time, or, more specifically, the fact of time: pictures are evidence of living in the now. Sitting with those photographs in our Brooklyn living room, I wanted to name everything I saw, because I was already aware of how time would often forget us. Or because people made you something other than what you were when they used their imprecise or prejudiced language to describe you.

Part of the heartbreak of listening to my mother’s guests was knowing that, at some point, they would misremember other people. Photographs proved that what you remembered wasn’t necessarily the truth; they confirmed certain facts. That what’s-his-name had black hair, not brown, or that they once smoked, or that they went fishing. Time is awful to us because it makes us characters in a story that isn’t or wasn’t always our story. Time is as wicked as my much-disliked grandmother who didn’t like being photographed at all. A picture can change what time does to us by framing us in its own time—the time the picture was taken, the photographer’s and subject’s time. Photographs rescue us from neglect.

I didn’t want anyone in that box of photographs to be forgotten because I didn’t want to be forgotten. I didn’t want my mother to be forgotten either, or how I must have looked in the eyes of her love, or hoped-for love. Is God a camera, recording who we are and who we wish to be “objectively”? I wrote down people’s names on the backs of photographs to fix the images in my mind. The images themselves were so complex—look at them, they shimmer with perception and are evidence, at times, of trying to see just who you really are, or long to be.

Advertisement

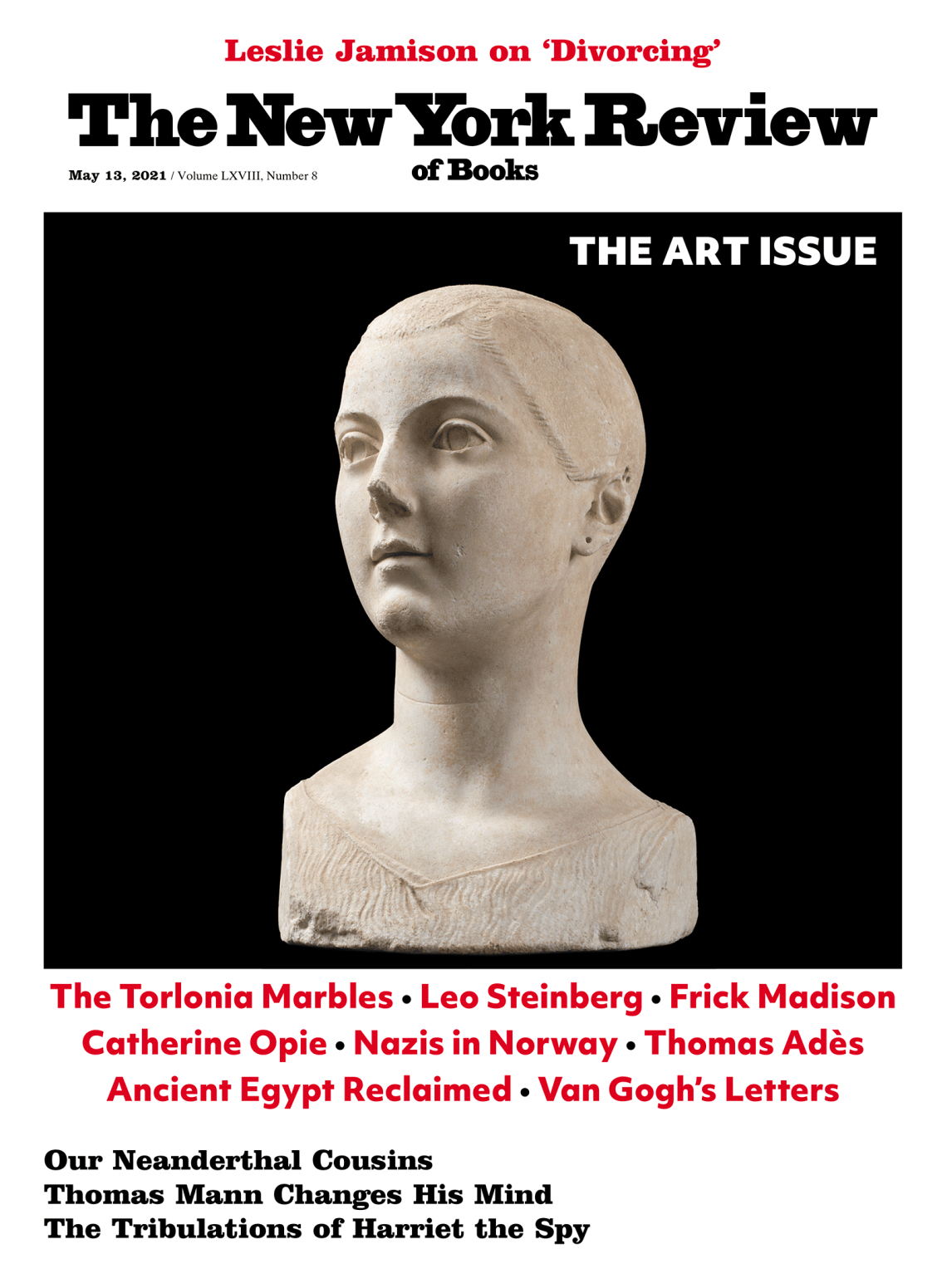

I wonder if my interest in Catherine Opie’s pictures has something to do with her desire not to forget, too. Because a lot of her subjects—queer subjects, people of color, artists—are prone to be forgotten in a forgetful world, a place where the desire to fit into some preexisting structure messes more people up than one might think. I have always distrusted that impulse—the impulse to belong. My resistance vis-à-vis conformity is growing crusty now as I age, but underneath the rust of experience beats, still, the heart of a guy who’s mystified by the will to conform. Conform to what? To some idea of what makes an artist? What makes a “correct” sexuality? How can we trust pretense? It’s a defense, untrue to the soul and the photograph.

Opie rejects that impulse—the impulse to conform—in people, in the world. Which is not to say she is averse to artifice. Opie’s particular gifts, or at least some of them, have to do with waiting for the “decisive moment,” when artifice meets truth—none of us tells the truth about ourselves all the time. We must dress the truth up in order to make bearable the reality of being. But we can’t dress up the soul. Sometimes the soul is hopeful or battered or a combination of both, and if you look closely enough, you can see it radiating out of the eyes of Opie’s subjects. That’s what she’s waiting for in her sittings: the reflection that reveals who we are under our carefully chosen clothing, our stillness and silence.

In short, Opie is interested in the status of the soul, where we are on the inside at the time she’s taking the photograph. What’s happening then? Are we examining our story as she examines us? Where does the time go when we’re being photographed? Or does sitting for one’s portrait encourage further reflection about how time makes us many people at once? Lovers, parents, performers, stars.

I am not of the opinion that people are consciously or entirely pretending when their portrait is being made; I think they’re doing the best they can under the circumstances. First of all, they’re being looked at and trying to look like “themselves” while being observed under the lights as time weighs on them, and as the photographer frames them in time. It’s an amazing exchange, and I think that’s what Opie’s pictures reveal—not only what that collaboration looks like but what it looks and feels like to be remembered.

This Issue

May 13, 2021