In his diary for May 6, 1997, the English essayist and playwright Alan Bennett—a trustee of the National Gallery, London, and an enthusiast of old master paintings—left an unexpectedly dyspeptic account of a visit to the Frick Collection in New York (his first in over thirty-four years). In search of somewhere to sit, he noted:

So I end up in the picture gallery, where there are a couple of benches—and a couple of Rembrandts, too, and a brace of Turners, a Velázquez and a Vermeer, the arrangement, roughly, portrait-landscape-portrait-landscape all round this dark, glass-ceilinged room. None of the paintings is shown to advantage, most looking dull and hung so close to each other as to make them difficult to take in on their own. Thus there’s a painting of Philip IV by Velázquez hung next to Vermeer’s Lady with Her Maid and a self-portrait of Rembrandt in old age; none is lit, they don’t complement one another, and together look like a trio of mud-coloured pictures.

Bennett was immune to the charms of an installation intended to evoke—and, in certain cases, replicate—the founder’s arrangement of paintings, sculpture, and decorative arts in his Gilded Age mansion. With London’s Wallace Collection in mind, perhaps—where the collection bequeathed by Sir Richard Wallace’s widow must still be “kept together unmixed with other objects of art”—Bennett assumed that the arrangements in the Frick were unchanging, “by the terms of its endowment.”

In fact, the museum is an agglomeration of spaces (and, to a degree, of collections) that have evolved over time. The house at 1 East 70th Street commissioned by the industrialist Henry Clay Frick (1849–1919) from the architectural firm Carrère and Hastings in 1912 was transformed into a museum in 1935 with the addition of John Russell Pope’s Garden Court, Oval Room, Music Room, and East Gallery. The peaceful and expansive inner court, with its long pool and verdant plantings, is a signature space of the museum, but neither Frick nor his wife, Adelaide Childs, ever saw it. (They died in 1919 and 1931, respectively.) In 1977 a small one-story pavilion in seventeenth-century French style designed by John Barrington Bayley was added to the eastern façade, and beside it, Russell Page’s 70th Street Garden.

Most recently, in December 2011 the outdoor garden portico on Fifth Avenue was enclosed and transformed into a naturally lit gallery to house the East Asian and Meissen porcelain given to the museum by the collector Henry H. Arnhold. Since then, Jean-Antoine Houdon’s extraordinary life-size terracotta statue Diana the Huntress, acquired in 1939, has been shown in a commanding position in the Portico Gallery’s rotunda. Yet as Adam Gopnik notes in his foreword to The Sleeve Should Be Illegal and Other Reflections on Art at the Frick—an anthology of sixty-two essays by artists, writers, filmmakers, and musicians on their favorite works—despite the patient explanation of the Frick’s curators regarding the various movements within and around the collection, the presumption that the Frick is a museum that does not change remains deeply rooted, and offers reassurance to many of its visitors.

After a protracted, widely covered, and at times contentious campaign to upgrade and extend the Frick’s building and facilities—launched in June 2014 with the announcement of a fairly disastrous expansion plan by the architectural firm Davis Brody Bond that entailed building over Page’s 70th Street Garden—in June 2018 the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission finally approved the Frick’s “revised application” for the expansion of the museum under the direction of Selldorf Architects. (Beyer Blinder Belle was hired as the executive architect.) The question of how and where to display the highlights of the collection during the projected three years of demolition and rebuilding was ingeniously resolved when the trustees decided to take over the Breuer Building at 945 Madison Avenue, which had been leased by the Whitney Museum of American Art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for eight years beginning in 2015. (In May of that year the Whitney decamped to Renzo Piano’s majestic new building on Gansevoort Street.) The Frick gained access to the building in September 2020, following the Met Breuer’s valedictory exhibition, “Gerhard Richter: Painting After All,” scheduled to run from March 4 to July 5, 2020, but which, because of Covid-19, was on view for barely a week, closing—like so much else in the city—on March 12.

While only four blocks from the Frick, Marcel Breuer’s building for the Whitney enshrined the values of an altogether different sector of the art world. Commissioned in July 1963 by the trustees of the Whitney—which since 1954 had been housed at 22 West 54th Street, adjacent to the Museum of Modern Art—to be constructed on a relatively small corner lot in the heart of the (then) gallery scene for modern and contemporary art, it opened in September 1966. The building is an inverted ziggurat with cantilevered floors, whose façade of flame-treated polished granite is punctuated by trapezoidal windows of various sizes—one overlooking Madison Avenue, six overlooking 75th Street—attached “like mysterious ornamental brooches, to the blocky exterior.”1 The Whitney’s interiors were primarily bush-hammered concrete walls, with board-formed concrete wall bases and precast-concrete gridded ceilings. Flooring was predominantly natural-cleft bluestone pavers, with walnut parquet on the second floor, since the museum needed a space for dancing. The galleries on three floors were open plan, unimpeded by columns or pillars, to be partitioned by floor-to-ceiling modular panels. A masterpiece of the new Brutalism by a Bauhaus luminary, deemed fitting to be “the housing for twentieth-century art,” it might seem the least-well-suited temporary home for a collection of (primarily) European masterpieces from the fifteenth to nineteenth centuries, intended to be seen in interdisciplinary arrangements in a domestic setting.

Advertisement

That this is manifestly not the case—the installation at Frick Madison (as the temporary arrangement is called) is extraordinarily satisfying, elegant, thoughtful, and respectful at every turn—is due in part to the Met’s superb restoration of the interiors of Breuer’s building, including the beautiful stair tower, with its cast terrazzo and exquisite finishes. Systems were upgraded throughout, obsolete interventions made after 1966 removed, floors and walls cleaned and refurbished—the new walnut parquet was modeled on an original remnant found inside a closet—and a large digital wall added to the redesigned lobby. Of course, the greatest credit goes to the Frick’s curatorial team—including both former and newly appointed curators—led by Deputy Director and Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator Xavier F. Salomon and curator Aimee Ng, working with Annabelle Selldorf of Selldorf Architects, exhibition designer Stephen Saitas, and lighting designer Anita Jorgensen. Saitas and Jorgensen have worked with the Frick curators on temporary exhibitions and displays for almost two decades and know the collection intimately.

Installed over three floors, showing around two thirds of the 470 works formerly on view at 1 East 70th Street—with nearly all the major paintings and sculptures included, as well as a handful of new acquisitions, some donated as recently as 2020—the collection is laid out in chronological order, by school (and, where possible, by artist) and by media, with sculpture and the decorative arts given their own galleries. No attempt has been made to replicate the display in Frick’s mansion, with its “acres of velvet,” but the curators have kept faith with certain organizing principles that governed the presentation of the collection there. Paintings are not behind glass; sculptures, decorative objects, and porcelains are not in cases (for the most part); there are no stanchions or barriers; and only a handful of the smaller Renaissance bronzes are shown in vitrines. Maintaining such direct and unmediated access to individual works of art—for the first time I was able to see (if not actually decipher) the notes on the score in Vermeer’s Girl Interrupted at Her Music—means that children under ten are still not admitted.

More radically, the curators have resisted any desire to provide introductory wall texts or explanatory labels. As in the Frick mansion, the visitor receives A Guide to Works of Art on Exhibition, printed on good paper, which follows the traditional design by the Oliphant Press. Information on all the works is also provided through a smartphone app. However, as before, at Frick Madison no photography in the collection is permitted, and on the day I visited the guards were vigilant in enforcing this.

In a series of carefully calibrated galleries, rooms, and bays, and following a spare, almost minimalist approach, Salomon and Ng have chosen to show the works on a variety of gray walls, with sculptures placed on new, rough-hewn pedestals. These glorious sequences also keep faith with Breuer’s recommendations for the display of art in his new museum. In the Architect’s Report that he prepared for the Whitney trustees in November 1963, he noted that the “essential requirement” for the interior exhibition spaces was that they provide “a simple, uniform and unpretentious background for the paintings and sculpture.” In German-inflected syntax, Breuer noted in his comments for the board presentation:

Simplicity and background-character of the gallery spaces with the visitors [sic] attention reserved to the exhibits…all walls and panels are light grey, the concrete ceiling a related grey, and the split slate floors another related darker grey.

Indeed, the palette chosen for Frick Madison—Manor House Gray, Pavilion Gray, Kendall Charcoal, and Rockport Gray—would surely have gratified Breuer.

At the beginning of each floor, the viewer is greeted by masterpieces of bronze, marble, and terracotta sculpture. On the second floor, devoted to Northern European painting from Hans Memling to Vermeer, visitors first encounter the Angel, cast in 1475 by Jean Barbet, a Lyonnais cannon maker, and one of the very few surviving monumental bronzes from this period. Hans Holbein’s portraits of Sir Thomas More and Thomas Cromwell, painted five years apart, still face each other as they traditionally have, but are now hung alone, unencumbered. Aesthetically, there is no contest. Hilary Mantel may have rehabilitated Henry VIII’s chief minister, but Holbein’s portrait of Cromwell as Master of the Jewel House is at best a poorly preserved original. The quality and condition of Sir Thomas More are simply miraculous. Rooms devoted to Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Van Dyck follow, and in the last all eight of the Frick’s portraits by Van Dyck are assembled in groupings that chart his progress from Genoa via Antwerp to the court of Charles I.

Advertisement

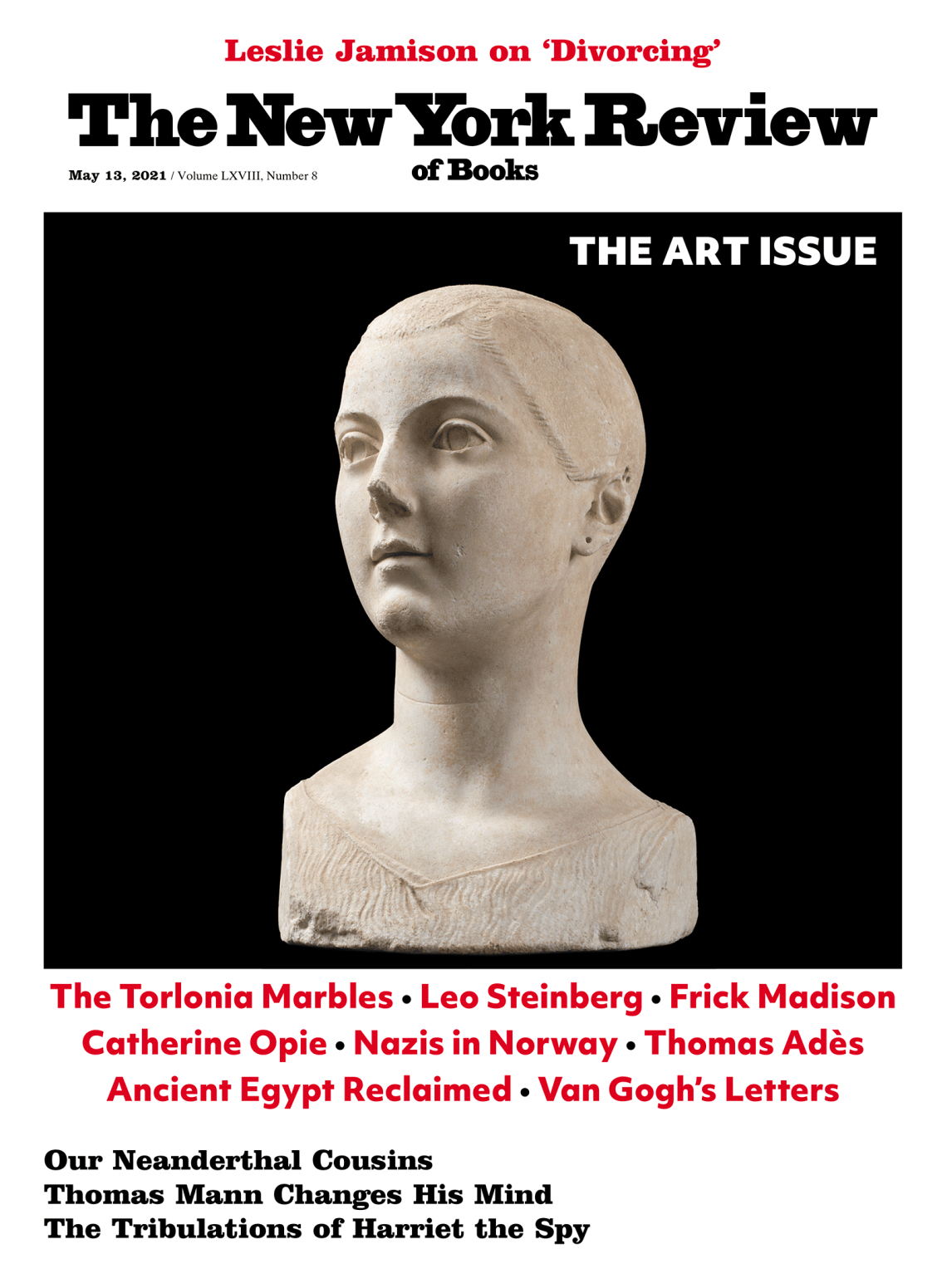

The third floor, devoted to Italy and Spain, is introduced by a trio of Renaissance female portrait busts in marble. The early Italian Renaissance paintings favored by Frick’s daughter, Helen Clay—founder of the Frick Art Reference Library—which include panels by Cimabue and Duccio, and a number of works from Piero della Francesca’s altarpiece for the church of Sant’Agostino in Borgo San Sepolcro, have been liberated from the Enamels Room of the Frick mansion to take possession of their own gallery. Exceptionally, the Frick’s most significant Asian works, two seventeenth-century Indian carpets woven during the reign of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan and restored in 2005, are placed in the following room. In the next gallery, riotously colored and fancifully mounted European and Asian porcelain acknowledges the founder’s passion for Qing Dynasty figures and vessels as well as the much more recent additions of works from the Meissen and Du Paquier manufactories.

From here one enters the grandest space on the third floor, a sala devoted primarily to sixteenth-century Italian painting and sculpture, with Veronese’s majestic allegories—The Choice Between Virtue and Vice and Wisdom and Strength—dominating the far wall. In the one overtly theatrical element of the entire installation, Francesco da Sangallo’s bronze statuette St. John Baptizing presides in the center of this room, set high atop a replica of its original base, the marble font designed by Giovanfresco Pagni for the church of Santa Maria delle Carceri in Prato. Commissioned in 1534 by the greengrocers and melon sellers of the town to adorn the stoop that one still encounters almost immediately upon entering the church, the saint would have been set on high—holding his little bowl aloft and pouring the holy water with which he baptized the faithful.

In the most poetic iteration in Frick Madison, west of the gallery of Titians and Veroneses is a small chamber occupied by a single painting, Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert (see illustration at beginning of article). A work that celebrates grace and love, it is bathed in natural light that enters through one of the windows that give onto East 75th Street.

Passing through a virtuosic display of Renaissance bronze statuettes choreographed on long shelves in rhythmic sequences, with masterpieces by Bertoldo di Giovanni, Riccio, Antico, and Severo da Ravenna—all of whom have been the subjects of monographic exhibitions (and catalogs) by Frick curators—in cases of honor in the center of the room, the visitor concludes the tour of the third floor in a long gallery devoted to Spanish painting from El Greco to Goya. While one expects to be swept away by Velázquez’s King Philip IV of Spain, which was sensitively restored in 2010, another revelation here are the Frick’s two Spanish full-lengths, which have never appeared more authoritative and impressive. Vincenzo Anastagi, in field armor—the forty-four-year-old sergeant major of Castel Sant’Angelo seen in momentary repose in El Greco’s swagger portrait—commands the room with his suspicious, unflinching gaze. It has no effect whatsoever on the muscular blacksmith in Goya’s Forge on the opposite wall, who is about to strike the molten sheet with his sledgehammer. A powerful, modern history painting—by no stretch of the imagination can these blacksmiths’ apprentices claim to be Vulcan’s assistants—such a respectful image of pre-industrial labor is still unexpected in the collection of the steel magnate who was responsible for the violent breakup of the Homestead Strike in July 1892.

The visit concludes on the fourth floor, which shows French and British works from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—from Rococo to Impressionism—in galleries where the ceilings are at their highest: 17′ 6″, as opposed to 12′ 9″ on the lower floors. In the mid-1960s, Breuer had arrived at this ceiling height “in consideration of the increasing size of contemporary painting.” And so galleries intended to house Color Field and Abstract Expressionist canvases are now home to grand-manner English full-lengths, James McNeil Whistler’s portrait commissions, and, unforgettably, Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s Progress of Love, shown in the two sequences in which the series was produced.

As on the other floors, upon entering the visitor first encounters sculpture: marble portrait busts by Houdon and a terracotta clock by Clodion. A group of the finest eighteenth-century French cabinet paintings follows, but the chief beneficiary of this installation is the room devoted to the decorative arts. Here Balthazar Lieutaud, Ferdinand Berthoud, and Philippe Caffiéri’s astonishing Longcase Regulator Clock, formerly hiding in plain sight at the foot of the staircase leading up to the mansion’s second floor, reveals itself to be among the most elaborate and sumptuous timepieces produced during the ancien régime. The room is further anchored by Jean-Henri Riesener’s Secrétaire and matching Commode, made around 1780 for Queen Marie-Antoinette, to furnish her apartments at the Château de Saint-Cloud. In the second half of the eighteenth century, in royal and aristocratic residences, a chest of drawers (commode) was often paired with a tall writing desk (sécretaire), with shelves and compartments inside. Made of marquetry veneered with precious and exotic woods of various hues—which have faded over time—both pieces were initially even more splendid in appearance than they are today. Riesener reworked them a decade later for the queen’s apartment in the Tuileries palace, where the royal family had been compelled to reside after being escorted back to the capital from Versailles in October 1789. The Side Table in Blue Turquin marble with exquisite gilt bronze mounts designed by Pierre Gouthière, one of the museum’s masterpieces of decorative art, has for years sat uncomplainingly in the North Hall underneath Ingres’s much-loved Comtesse d’Haussonville.

All three pieces of furniture are now enhanced by garnitures of Sèvres and Meissen porcelains, which are raised a respectful distance, mounted on austere ledges with discreet panels behind them, and given the same reverence as sculpture. These include such rarities as the boat-shaped Sèvres Pot-pourri à Vaisseau, one of only ten surviving examples; the coral-colored and misleadingly named Vase Japon, from the same manufactory, with its silver-gilt mounts, modeled on a Han Dynasty bronze Yu vase from the Chinese imperial collections; and a Pair of Candelabra, with exuberant gilt-bronze mounts by Gouthière, that adorn early Meissen vases, one of which is a late-nineteenth-century replacement. (Look closely, as you now can, and you will be able to identify which white vase is the genuine article.)

The long gallery devoted to eighteenth-century British painting—in many ways Frick’s favorite school, and the most expensive for Gilded Age collectors—brings together all of the museum’s works by Thomas Gainsborough. It also includes a trio of three-quarter-length portraits by William Hogarth, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and Sir Thomas Lawrence, each of which is notable for a resplendent item of scarlet apparel: the eye travels from Miss Mary Edwards’s day dress, to General John Burgoyne’s jacket, to the feathers of Lady Peel’s hat. Galleries of French painting that include portraits by Jacques-Louis David and Ingres and Impressionist paintings by Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir—seen here for the first time in companionable juxtaposition—lead to the two rooms devoted to Fragonard’s Progress of Love: the culminating sequence on this floor and one of the most inspired spaces of the entire installation.

The four large panels in this pastoral romance, around ten feet high and seven feet wide—commissioned from Fragonard by Madame du Barry, the mistress of Louis XV, for her pavilion in Louveciennes in 1771 and rejected by her the following year—hang in the order in which they were intended to be seen on the walls of her Salon du Cul de Four. On one wall is the first pairing: The Pursuit and The Meeting. The story reaches its crescendo on the opposite wall with The Lover Crowned at left and concludes with Love Letters, where the preternaturally young couple review their courtship in perfect amity. At Frick Madison this magnificent series is anchored by the monumental trapezoidal window that gives onto Madison Avenue. The ten additional canvases that Fragonard painted twenty years later in a more autumnal palette for his cousin’s villa in Grasse—two large vertical canvases, Reverie and Love Triumphant, four overdoors of crazed cupids, and four slim, decorative panels of hollyhocks—are displayed together in an adjoining gallery.2

With daylight bursting upon them, Fragonard’s four canvases for Madame du Barry have never looked so vibrant or so lush. Yet Breuer was not an advocate of natural light and banished windows from his galleries. While he recognized that “lighting is probably the most important single element of a museum,” he relied almost exclusively on electricity to provide it, claiming that windows “have lost their justification of existence.”

Research on some of the collection’s most familiar (and well-studied) works has been published in a new Diptych Series, launched in 2018, which pairs a contemporary writer or artist with a Frick curator. Hilary Mantel writes “A Letter to Thomas More, Knight,” admonishing him, “You’ve not shaved to meet the painter,” while Salomon discusses (among other things) the relationship of the Frick’s panel, painted on Eastern Baltic oak felled around 1496, to “the most extraordinary painting Holbein created in England in 1527,” the group portrait of More with three generations of his family, probably commissioned in celebration of his fiftieth birthday. (Some 142 inches in length, the canvas was most likely destroyed in 1752 by a fire in Kroměříž Castle in Moravia.)

The master potter, installation artist, and historian Edmund de Waal inhabits Pierre Gouthière, chaser and gilder to the courts of Louis XV and Louis XVI, and channels him at work. Caressing the gilder’s little chisels and punches in the palm of his hand, de Waal marvels at these tools “for stippling the surface of a berry…for feathering an acanthus leaf…for smoothing and burnishing out the folds of a ribbon.” Charlotte Vignon, the Frick’s former curator of decorative arts, deconstructs the Pair of Candelabra, a recent acquisition. These hard-paste porcelain vases with transparent white glazes—imitating Chinese models—were created at Meissen between 1713 and 1720 in the utmost secrecy by the alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger, who since 1701 had been pressed into the service of Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony. A half a century later, Gouthière would be commissioned by the Duc d’Aumont—his most avid patron—to provide bronze mounts with exquisite Arcadian motifs by which these vases were transformed into candelabra. D’Aumont died in 1782 before the work was completed, owing Gouthière 20,000 livres and forcing him to declare bankruptcy five years later.

Constable’s White Horse inspires a lyrical reminiscence of a family outing as a nine-year-old to the arid countryside outside Johannesburg by the South African artist William Kentridge, who finds himself these many years later still “longing for the green.” Ng traces the gestation of the first of Constable’s six-footers, illuminating the topography and methods of transportation it depicts and discussing the forty-three-year-old artist’s idiosyncratic practice of working concurrently on full-scale sketches the same size as his exhibition pictures. Channeling Florine Stettheimer, the artist Maira Kalman produces a suite of affectionate gouaches in homage to both Rembrandt and the Frick: entitled Poor Rembrandt, they are also for (pour) the painter. In Salomon’s essay on Rembrandt’s Polish Rider, he offers the most comprehensive account to date of this mysterious painting’s nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Polish provenance, following its presentation to King Stanisław August in 1791. The sale of The Polish Rider to Frick by Count Zdzislaw Tarnoski in April 1910 was part of the family’s patriotic effort to raise funds for the repurchase of ancestral lands that they were seeking to keep in Polish possession.

If I have a favorite in the series so far—and volumes on Riccio, Paulo Veneziano, Fragonard, and Monet (among others) are forthcoming with contributions from James Fenton, Nico Muhly, Alan Hollinghurst, and Olafur Eliasson—it would be the diptych devoted to Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid, a collaboration between the filmmaker and screenwriter James Ivory and the Frick’s former associate research curator Margaret Iacono. Ivory conjures Cornelia, the daughter of a wealthy Delft merchant, who is being courted by two suitors. One, very rich and devout, is championed by her father and has recently seduced her maid, Amalia, in a consensual and brief coupling, with no consequences. The other, Adriaen Gansvoort, whom the mistress favors but of whom her father disapproves, is handsome, enterprising, and poor. Cornelia will marry neither, but when we encounter her in Vermeer’s painting she still looks forward to receiving Adriaen’s letters. She holds them against her cheek, saves them all in a little locked box, and years later, now a mother of four, will occasionally be caught by Amalia reading them when she thinks no one is looking.

Ivory’s speculations are balanced by one of the most interesting technical discoveries in recent Vermeer scholarship, made by Iacono in collaboration with colleagues from the Metropolitan Museum’s Departments of Paintings Conservation and Scientific Research. It has long been known that there is a curtain in the background of Mistress and Maid. It is very hard to see, and most viewers assume, reasonably enough, that the two women are set against an empty space. Using non-invasive techniques such as infrared reflectography and macro X-ray fluorescence, it was discovered that, after blocking in his two protagonists, Vermeer sketched a large tapestry with a group of four female figures and a border on the right in the background. The tapestry appears to be have been based on Four Servants, after a design by the Flemish artist Jacob Jordaens, woven in Brussels by the workshop of Jan van Leefdael around 1650.

Anticipating, perhaps, the visual overload that this would cause and how distracting the final composition might appear, Vermeer painted out the tapestry and replaced it with a green curtain in the final composition, which is drawn aside to reveal the servant as she delivers the letter. Over time, the pigments in this curtain have discolored to an almost imperceptible brown. (Technical investigations also confirmed that the blue tablecloth in the foreground was originally a dark, translucent green, likely the same color as the curtain.)3

As research in its various forms continues on the works in the Frick Collection—many of which have been introduced during the pandemic to an even broader audience through the YouTube phenomenon Cocktails with a Curator, in which each week one of the Frick’s staff offers a recipe for a cocktail and then drinks it while discussing a work in the collection—we can only speculate as to both the sensational discoveries and refinements in scholarship that lie in store. But for the moment we can celebrate unreservedly the collective effort and imagination that have brought Frick Madison to life at a very challenging moment in the city’s history. So “noble and life-like” did visitors to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge in the spring of 1910 find Holbein’s Sir Thomas More—where it was on loan for five months—that many were seen to “uncover their heads, as though in the actual presence of the keen-eyed Chancellor.” If we still wore them, we would be removing our hats again as we encounter masterpiece after masterpiece in its temporary new home at Frick Madison.

This Issue

May 13, 2021

-

1

Barry Bergdoll, “Marcel Breuer: Bauhaus Tradition, Brutalist Invention,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 74, No. 1 (Summer 2016), p. 37. ↩

-

2

For a full account, see my Fragonard’s Progress of Love at The Frick Collection (The Frick Collection/D Giles, 2011). ↩

-

3

The technical findings are well illustrated and thoroughly discussed in Dorothy Mahon, Silvia A. Centeno, Margaret Iacono, et al., “Johannes Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid: New Discoveries Cast Light on Changes to the Composition and the Discoloration of Some Paint Passages,” Heritage Science, Vol. 8, No. 30 (March 27, 2020). ↩