If ever an artist needed a degree of protection against his public, surely it is Vincent van Gogh. Reproductions of his most emblematic paintings, especially the gyrating nightscapes and the blazing series of sunflower studies made in his late years, adorn countless bedrooms, living rooms, and bathrooms all across what used to be known as the developed world. The popularity of the works executed in the great flowering of this last period, which began around the time of his revelatory visit in the autumn of 1885 to the newly completed Rijksmuseum, in Amsterdam, and ended when he died less than five years later at the age of thirty-seven, is unparalleled. Of the great ones among his contemporaries, and there were many, only Degas can come near to rivaling him as a mainstay of interior decoration.

What would the Dutch master make of his posthumous fame among the bourgeoisie and the billionaires alike? We can trace fairly accurately the foundations of the Van Gogh myth to the 1934 novel Lust for Life by Irving Stone and the 1956 movie of the same title based on the book, directed by Vincente Minnelli and starring Kirk Douglas as Van Gogh and Anthony Quinn as Paul Gauguin. Stone made the plot of the novel from his research among Van Gogh’s correspondence, a three-volume edition of which had been published in 1914, edited by the painter’s sister-in-law Jo van Gogh–Bonger. The novel does as blockbusters do, and so does the film, but both make a decent attempt at portraying the life, and of course the lust, of this truly tormented artist. In the movie, Douglas bears a remarkable resemblance to the Van Gogh of the many self-portraits. He overacts wildly, though not so wildly as Quinn—“I’m talkin’ about women, man, women. I like ’em fat and vicious and not too smart”—and out of such caricatures are legends made.

To be fair to the novelist and the filmmakers, the life, and to some extent the paintings, are the stuff of legend. Although he produced thousands of works of art in his pitifully short time on earth, Vincent—as, following his own example, we shall call him—failed to sell a single painting in his lifetime, despite the fact that his brother Theo was a prominent Paris art dealer who, among other business coups, made a reputation for Gauguin and a fortune for Claude Monet. Although he suffered through periods of deepest doubt, Vincent knew that one day his work would be recognized for its true worth. All the same, even in his most exalted transports of optimism, and there were some, he could not have dreamed that his jarringly revolutionary paintings would one day rise so high in popular regard.

There were numerous editions of the Van Gogh letters before the one assembled by Van Gogh–Bonger after the death of her husband, Theo van Gogh.1 The first scholarly edition, by the English critic Douglas Cooper, was published in 1938, while the standard collection was established by the painter’s nephew, Vincent Willem van Gogh, and published between 1952 and 1954. Then, in 1994, the Van Gogh Museum and the Huygens Institute, in the Netherlands, brought together a team of editors and translators to produce a complete edition of the 820 surviving letters, which was published in 2010 in six sumptuous volumes. Vincent van Gogh: A Life in Letters is a representative selection of seventy-six of those letters.2

It is a splendid achievement, the letters shrewdly chosen, meticulously edited, and beautifully printed. At the outset, a note to the reader assures us that “absolute fidelity to Van Gogh’s original words is the fundamental principle underlying this English language translation, reproducing them as closely as possible, consistent with readability, without interpretation.” A notable feature of this one-volume edition, as of its much more extensive predecessor, is the ingenuity exercised in the choice of illustrations, which brilliantly illuminate and inform the text.

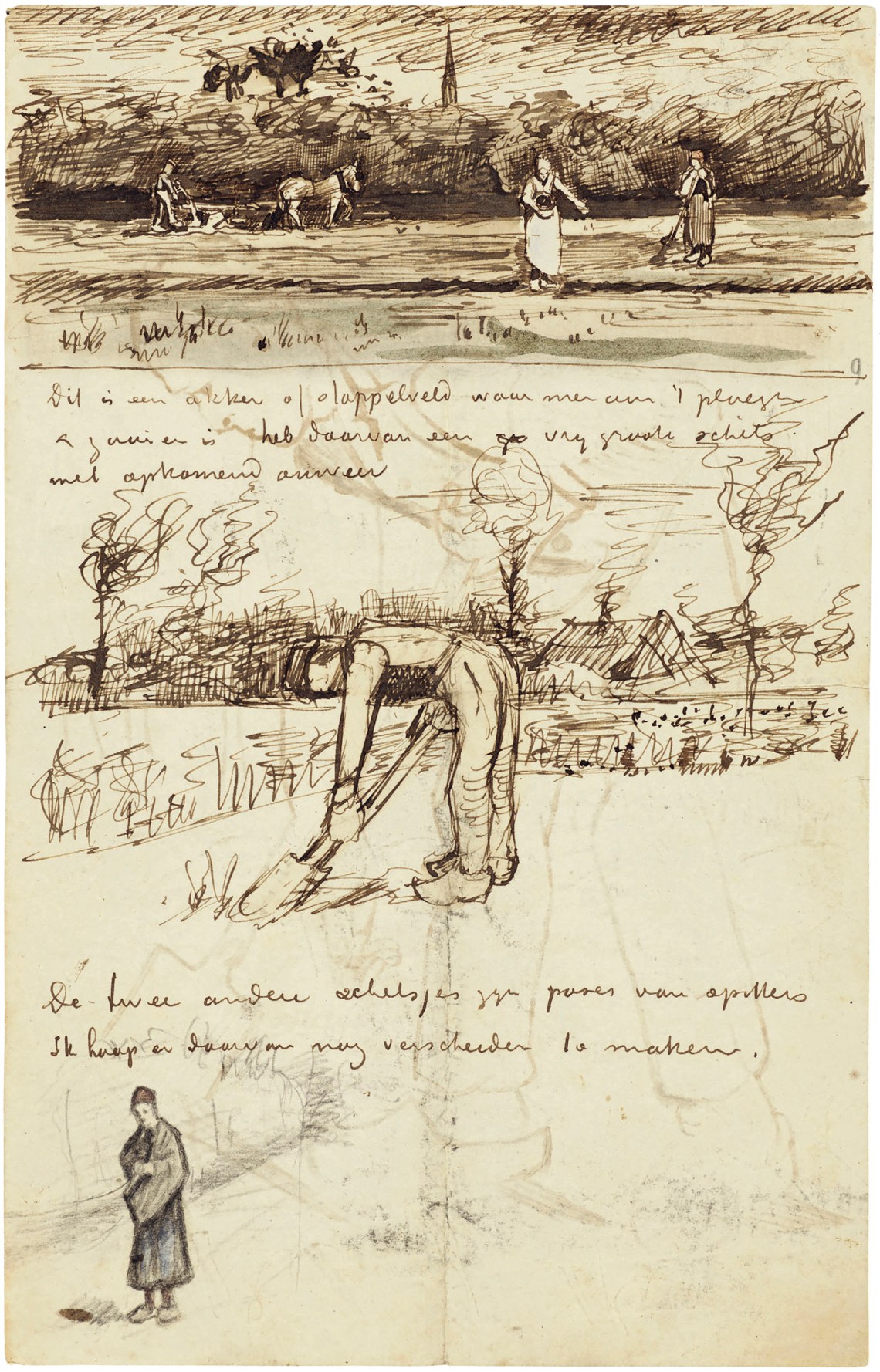

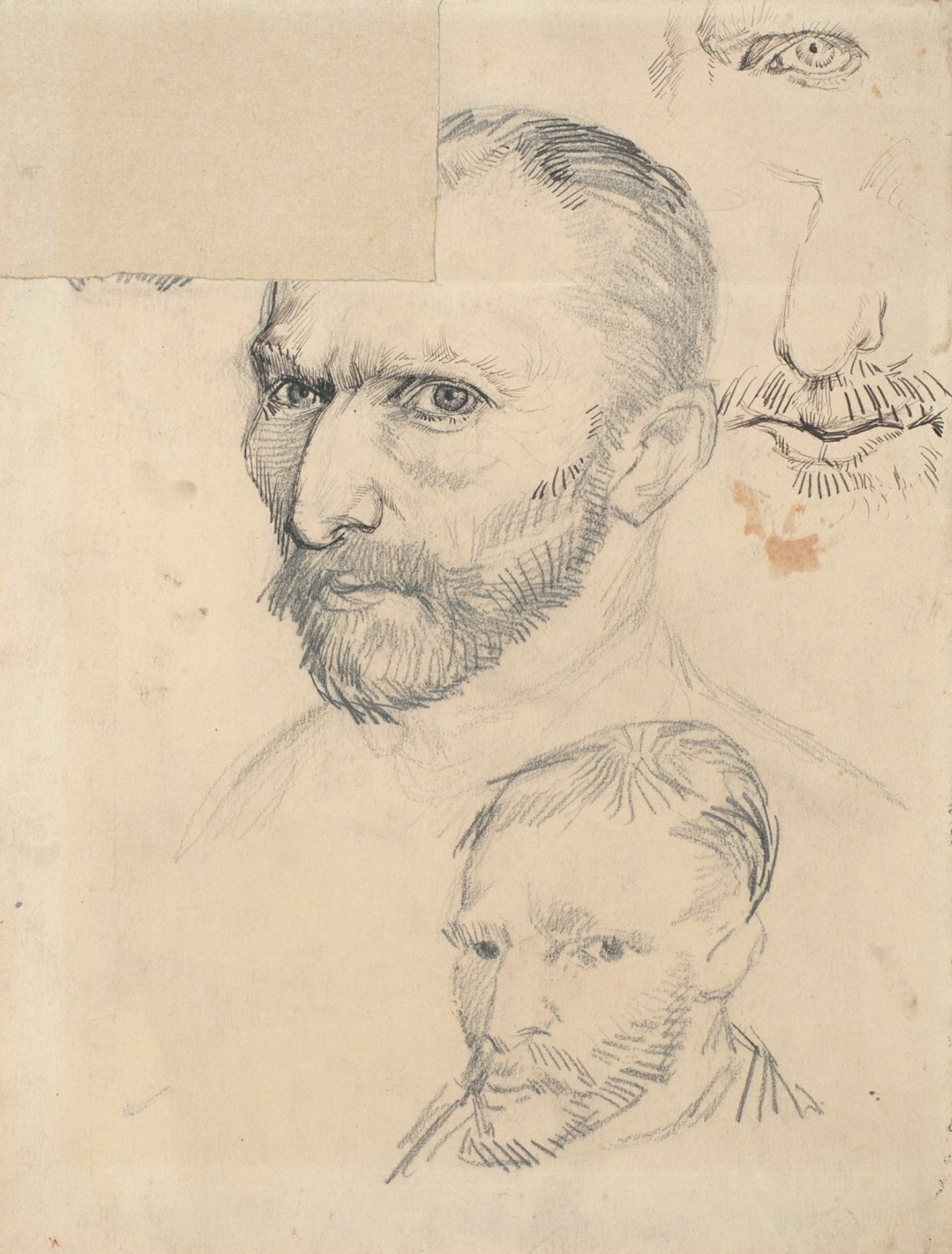

Regarding the title, however, a caveat must be entered: the letters provide a detailed portrait of the artist, of his thought, and of his working methods, but they hardly amount to a life—even the six-volume edition, for all its splendors, doesn’t do that.3 Vincent was one of the great letter writers, perhaps the greatest among painters, and vastly prolific in his correspondence, but he was too busy working, and insufficiently interested in himself and his daily affairs, for this selection to amount to an epistolary biography. The individual letters are frequently very long—though never long-winded—with some postscripts longer than the letters to which they are appended; they are scattered throughout with notations, marginalia, and pen-and-ink sketches, so that they make for handsome and absorbing documents in themselves; but they do not tell us very much about Vincent’s day-to-day life. Surely one of the loneliest among the great artists, he lived perforce largely in his head.

Advertisement

Vincent came from a line of Protestant churchmen; his paternal grandfather and his father were both pastors in the Dutch province of North Brabant. The latter was an adherent of the so-called Groningen Movement, which rejected orthodox Dutch Reformist dogmas and emphasized instead the influence of divine grace upon the individual, who could find a direct way to God through the action of the spirit and the intellect. In his early years Vincent was, like Simone Weil, waiting on God, and after a great deal of struggle and torment his waiting was rewarded when he found at least a version of the divine not in realms above but in the doings of ordinary men and women, and in the sublime, rough beauty of the natural world mediated through painting and literature.

Devout though his parents were, they recognized early on that what the young Vincent needed most urgently was a good, safe job, to counter his already apparent neurasthenia and obsessive preoccupation with religion. In 1869, on the recommendation of a businessman uncle, he went to work as a junior apprentice at the Hague branch of the art dealers Goupil and Cie. There he was joined four years later by his younger brother Theo, who was to play a crucial part in his life and work—it is likely that without Theo’s spiritual and, more significantly, financial support, Vincent could not have survived as a painter.

Subsequently Vincent was transferred to the London and then the Paris branch of Goupil but was let go by the firm, gently but definitively, in 1876. He returned to England and found, of all things, a post at a school in Ramsgate, and later at the same school when it moved to London. He and another teacher were responsible for the twenty-four pupils from 6 AM to 8 PM; Van Gogh taught “a little of everything,” including French, German, mathematics, and “recitation,” and in his spare time did odd jobs about the school. Although he seems to have been a good teacher, what he really wished to do was preach the word of the Lord by way of the Gospels. Thus from the start he was suspended between art and religion, the two magnetic poles of his life.

It was ever his aim to paint the people, for the people, although he acknowledged, in his more candid moments, that “the people” had little time for art, and none at all for the version of it he was offering them. An impassioned visionary for whom painting was religion by other forms, he yet had his roots sunk deep in the soil, almost literally so when he lived among the peasant farmers and the mining communities of some of the poorest, bleakest regions of the Low Countries. He fairly brimmed with sentiment but was no sentimentalist, despite his unflagging enthusiasm for the pious simplicities of Jean-François Millet, the well-turned decorativeness of his cousin-in-law Anton Mauve, and the lacquered scintillations of Adolphe Monticelli, among others; bad artistic companions all, who led him to bash his head against the rock face of many a dead end. Few great artists have had such poor taste in art.

For all his proletarian sympathies, it would be a grave error to regard Van Gogh as naive or primitive, that is, as a painter driven exclusively by his instincts and the vagaries of his shaky mental constitution. In the matter of technique he lacked a natural facility, but at least this meant he would never be facile. His drawing was clumsy, as was Cézanne’s, and he spent years of drudgery trying to teach himself the knack of fixing the likeness of a face, the contours of a figure.

He was an untiring chaser of women, but it’s unclear which he desired more, a bedmate or a model. His womanizing got him into awful trouble again and again. His early love for the prostitute Sien Hoornik was the cause of some of his most violent arguments with his disapproving father, while a later object of his obsessive attentions, the neurasthenic Margot Begemann, marked the end of their relationship by taking a dose of strychnine, though she survived the suicide attempt. He contracted syphilis, probably on one of his regular visits to brothels, and suffered the effects of it all his life, though not so dreadfully as his brother Theo, who would die of the disease. Vincent’s resilience, his ability to cope with illness, poverty, and, at times, near starvation, points to a truth seldom remarked, that to make a life in art an artist must have unquenchable stamina; even Keats sang to the very end.

Advertisement

Vincent was consciously an intellectual, knew the classics, was widely read—as Mariella Guzzoni’s Vincent’s Books amply attests—spoke or at least wrote in four languages, knew intimately the work of his mighty predecessors, especially Rembrandt and Delacroix, and was as knowledgeable in the nuances of color theory as Seurat or Cézanne. In the early days his aim was to paint in black, the blackest black he could mix on his palette, and all the grays that are black’s variants—“light black,” as Clov laconically has it in Beckett’s Endgame.

The year 1885 saw Vincent’s breakthrough, when he produced what he recognized as his first truly successful painting, The Potato Eaters. To Theo he wrote, “You’ll hear—‘what a daub!’; be prepared for that as I’m prepared myself.” But he was determined nonetheless to “go on giving something genuine and honest.” The picture, he proudly acknowledged, looked as if it had been painted in soap, but colors are there, though in the subtlest gradations. There is, in this early, intentionally drab phase of his work, the sense of a world of color willfully suppressed but straining to break out and assert itself. He spoke of the painting as a woven fabric—“I’ve had the threads of this fabric in my hands the whole winter long, and searched for the definitive pattern”—and compared his working method to that of Scots weavers who, he wrote with stammering urgency to Theo, try

to get the very brightest colours in balance against one another in the multicoloured tartans so that, rather than the fabric clashing, the overall effect of the pattern is harmonious from a distance. A grey that’s woven from red, blue, yellow, off-white and black threads, a blue that—is broken by a green and an orange, red or yellow thread—are very different from plain colours—that is, they vibrate more.

Six months after The Potato Eaters came at last the great revelation, with Vincent’s visit to the Rijksmuseum. Here he discovered the glories of the art of the Dutch Golden Age, in particular Rembrandt and especially his Jewish Bride—“what an intimate, what an infinitely sympathetic painting”—but he was still immersed in those thrillingly authentic grays. To the side of Rembrandt’s The Night Watch he spotted another densely populated work, jointly by Frans Hals and Pieter Codde, in which there is a figure painted all in gray, “all one family of grey—but wait!” Into the gray are introduced tones of blue and orange and white, which lift the gray into another, “glorious spectrum.” In that “but wait!” we glimpse the first glint of dawn, though it would be some years yet before the light would finally break and flood Vincent’s palette with its harsh, joyous glare.

We like to romanticize Vincent’s journey to the South of France in 1888 as a form of artistic rebirth, and to an extent the romance is there. But Provence, for all its song and sunburnt mirth, was a hard place, and it gave Vincent a hard time. He settled first in Arles, finding eventually the famous Yellow House on place Lamartine that he shared for a couple of tumultuous months with Gauguin. From the start it was a precarious existence, made possible by the heroic generosity of Theo, who subsidized Vincent with a monthly allowance that was twice the salary of a high school teacher. For years Theo allowed his brother to maintain the face-saving fiction that the money was a long-term loan that eventually would be repaid bounteously when the art market came to its senses and began to buy Vincent’s work and pay a fortune for it. In his calmer, more realistic moments, Vincent knew there was scant hope of his ever being able to make a living from painting, and the knowledge tormented him.

Alone in Arles, he set himself to luring Gauguin south, to join him in forming an artistic brotherhood based in the Yellow House. This mad dream buoyed him up through many a long day and long, dark night:

I must tell you that even while working I never cease to think about this enterprise of setting up a studio with yourself and me as permanent residents, but which we’d both wish to make into a shelter and a refuge for our pals at moments when they find themselves at an impasse in their struggle.

Further on in the same letter we envisage him sitting back with a wistful sigh and pushing away, or seeking to push away, all the rejections and failures of the past: “At present, dimly on the horizon, here it comes to me nevertheless—hope—that intermittent hope that has sometimes consoled me in my lonely life.” Alas, he had fixed on the wrong man in whom to place so much of that intermittent hope. Gauguin was clever, protean, ever with an eye to the main chance, and poor Vincent was no match for him.

The two could not have been more dissimilar in temperament and artistic outlook. Gauguin was a committed symbolist, insisting that images of the world must be refined through the artist’s sensibility in order for them to be hammered into the burnished contours of art. For Vincent, as for Wittgenstein, the world was all that is the case. He made a few fainthearted efforts to embrace Gauguin’s aesthetic, but it was not for him. Gauguin, for his part, found Vincent’s work as gauche as it was garish. In a fever of anticipation, Vincent had decorated the walls of his guest’s bedroom with crowded images of sunflowers. “Shit, shit, everything is yellow,” Gauguin exclaimed. “I don’t know what painting is any longer!”

It couldn’t last. Two days before Christmas, 1888, Gauguin stormed out of the Yellow House, taking his brushes, paint, and fencing gear with him, never to return. On the same day, Vincent was stricken with terror at the prospect that his other, more dependable lifeline had been severed when he received word that Theo had become engaged to be married; the news brought about another, more immediate severance, when Vincent slashed off with a razor the lower part of his left ear. Having bandaged himself up as best he could, he went out into the winter evening in search of the friend who had abandoned him.

There was only one place Gauguin would have fled to, so Vincent, bearing the bloody morsel of ear wrapped in newsprint, marched off to the local brothel on the nearby rue du Bout d’Arles. Gauguin, he was told, was not there, so he gave the package to the doorman, asking that it be delivered to Gauguin’s favorite prostitute, Rachel (alias “Gaby”), accompanied by the message “Remember me.” Thereafter Vincent descended into the first of the devastating psychotic episodes that would return with hideous regularity until his death two years later.

One of the problems for the editors of Vincent van Gogh: A Life in Letters is that the painter tended to communicate with correspondents during the more uneventful periods in his life, and always sought to gloss over the tumult. In a letter to Theo of December 18, 1888, he signs off with a cheery valediction: “On behalf of Gauguin as well as myself, a good, hearty handshake to you all.” Four days later came the Gauguin debacle and its bloody aftermath. Of course, the doings of the day are not of the first consequence in the life of an artist, especially one so great as Vincent, for whom the mere business of existing is constantly subsumed into the work.

All the same, Vincent van Gogh: A Life in Letters is thoroughly engrossing. Vincent had a richly evocative prose style; he could have been a great critic, a fine novelist, perhaps even a poet. His descriptive writing is vivid and sensuous, and his extended meditations on art, on nature, and on the comédie humaine set him in a line with Balzac or the Goncourts. Even at the end of his life, ravaged by mental and physical ailments, mocked by street urchins and harassed by officialdom, he kept to his task of producing transformative works of art. Only months before his death, he wrote to the critic Albert Aurier from his cell in the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence about the challenge of painting cypress trees:

Until now I have not been able to do them as I feel it; in my case the emotions that take hold of me in the face of nature go as far as fainting, and then the result is a fortnight during which I am incapable of working. However, before leaving here, I am planning to return to the fray to attack the cypresses. The study I have intended for you depicts a group of them in the corner of a wheatfield on a summer’s day when the mistral is blowing. It is therefore the note of a certain blackness enveloped in blue moving in great circulating currents of air, and the vermilion of the poppies contrasts with the black note.

A great many of the letters are written in l’esprit de l’escalier, though the esprit is more than often very low indeed. Frequently we are presented, figuratively, with the spectacle of the painter sprawled at the foot of the steps, having been thrown out yet again by the scruff of the neck from this or that café, salon, or atelier. Can there ever have been anyone less clubbable? Socially, as in so many other ways, he was his own worst enemy. The tone of the letters consistently is that of a man still aflame after a violent argument, gradually subsiding into a hot puddle of guilt and shame from which now and then, in a renewed fit of rage, he surges up into yet another outburst of rancorous self-justification. On practically every page we seem to hear the slammed door, the kicked chair, the pen nib gouging into the writing paper, and the fierce little red-haired man hissing in fury through his teeth. If it were not all so sad, it would be comic.

In his calmer intervals, especially in the long, solitary evenings when he had nothing to do and no one to talk to, he sat down with pen and ink to try to extricate himself from the consequences of the day’s enormities. In the summer of 1888, after yet another family row, he admits to Theo that he is “a man of passions, capable of and liable to do rather foolish things for which I sometimes feel rather sorry.” This is, to say the least, an understatement; after the death of Van Gogh père, Vincent’s mother and sisters held him largely responsible for driving the old man to his grave by his impossible behavior, religious taunts, and constant squabbling.

These letters are the products of the terrible loneliness Vincent endured throughout his life, and from which he suffered deeply. He bemoans the lack of a companion, a soul mate, a friend. The great bulk of the letters are addressed to Theo, his most precious confidant and unfailing benefactor—“Money can be repaid, not kindness such as yours.” Long before he pinned his hopes on Gauguin he had urged Theo repeatedly to join him, in whatever latest hellhole he had condemned himself to, so that they might set up together a brotherhood of artists and make many masterpieces and lots and lots of money. There was no limit to the extent of his fantasies—he even demanded that Theo and his new wife abandon their marital home and come live with him and paint, all three of them.

Vincent had few consolations, but literature was one of them. In 1880, as Guzzoni tells us in Vincent’s Books, he wrote to Theo, “I have a more or less irresistible passion for books and I have a need continually to educate myself, to study, if you like, precisely as I need to eat my bread,” adding that “one has to learn to read, as one has to learn to see and learn to live.” Guzzoni’s book is charming, enlightening, and ever unpretentious. It is beyond her scope, she plainly admits,

to examine all of Vincent’s reading, to which other authors have devoted important studies. Rather, I attempt to map an artistic-intellectual journey through his favourites, in a continuous dialogue between his work as an artist and the key authors and illustrators that inspired him.

In this endeavor she succeeds admirably. Her book is appositely illustrated—the color reproduction is notably rich and convincing. She provides a dense range of references, from Dickens and Zola, Vincent’s abiding favorites, to volumes of Japanese prints like those that were such a strong influence on his work from the mid-1880s right to the end—an Eastern light bathes The Langlois Bridge at Arles and Fishing Boats on the Beach at Les Saintes Maries-de-la-Mer, both from 1888, and provides an especially rich glow in the delicate Almond Blossom of 1890, the year of his death.

Guzzoni pays particular attention to another of Vincent’s breakthrough paintings of 1885, Still Life with Bible, painted in October. In this dark-hued yet slyly chromatic work, some strong autobiographical points are made. The Bible depicted is the one that belonged to Vincent’s father, who had died only months before the picture was painted, and with whom he had quarreled to the end. The massive book, with its big, weighty pages and metal clasps, is a dominating presence at the center of the composition. Beside it there is a snuffed-out candle and a second, much flimsier volume.

The symbolism overall is plain—even Gauguin would have been impressed—yet pleasingly ambiguous. The crowded lines of sacred text seem at first sight painted in an overall shade of gray—“light black”—but a closer glance shows seemingly random slashes of blue, yellow, orange, and lavender. The page lies open at Isaiah 53:3—“He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.” The smaller, much less assertive volume, with a lemon-yellow cover, is the deceptively titled novel La joie de vivre, according to Guzzoni “one of Zola’s most pessimistic works.” Here Vincent is bidding a typically bitter farewell to a loved but much resented parent and cleaving to the brighter light of lands where the lemon trees grow, yet where sorrow also abounds. As his biographers Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith have it:

Through this seamless, spontaneous interweaving of personal preoccupations and artistic calculations, private demons and creative passions, Vincent had achieved an entirely new kind of art. And he knew it.

Not that you’re likely to see a print of Still Life with Bible, or anything resembling it, displayed on the wall facing you at the next dinner party you happen to attend.

This Issue

May 13, 2021

-

1

Van Gogh–Bonger deserves the highest credit for her dedication in establishing her brother-in-law’s posthumous reputation. As the editors of Vincent van Gogh: A Life in Letters write, she “made a huge contribution to the recognition of Van Gogh’s work.” ↩

-

2

The complete correspondence can be found at vangoghletters.org. But even if you have to save up, do buy one or other of the collections—if not the six-volume edition, then this shorter one. It is such a beautiful and satisfying object, a pleasure to handle, and sturdy enough to bequeath confidently to your heirs. ↩

-

3

For the details you must go to Van Gogh: A Life by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith (Random House, 2011), which, at not much short of a thousand pages, will tell you everything you might wish to know about the life, and possibly a good deal more. ↩