In his book Uneasy Peace (2018), Patrick Sharkey writes:

The videos of police violence have resonated so powerfully because they come at a time when there is no crisis of crime in most of the country, when every other form of violence in society has subsided.

Sharkey, a sociologist at Princeton and an expert on urban crime, was referring to the videos of the police killings of Eric Garner, Walter Scott, and twelve-year-old Tamir Rice in 2014 and 2015. But he could say the same thing about the video of Derek Chauvin pressing his knee into George Floyd’s neck. As Sharkey notes, for the last twenty-five years America has enjoyed what sociologists call “The Great American Crime Decline.” The United States is the safest it’s been in its history.1 But it’s an uneasy safety because it relies so heavily on morally repugnant and unsustainable methods—militarized overpolicing and mass incarceration chief among them.

As calls to defund the police grew louder after Floyd’s death, many people began to ask: Could the Great American Crime Decline be sustained without police? The question is complicated by the fact that in these relatively peaceful decades, the US has had the highest homicide rate of any high-income country, and according to preliminary data released in March by the FBI, it rose by 25 percent in 2020, when an estimated 20,000 people were murdered—more than fifty-six a day. But the number was high in 2017, too, when forty-seven people were killed a day, a rate roughly seven times higher than that of other high-income countries, driven by a gun homicide rate that is twenty-five times higher. As two recent books—Alex Kotlowitz’s An American Summer, a collection of journalistic vignettes, and Thomas Abt’s Bleeding Out, which draws on sociological and criminological research—demonstrate, the relationship between policing and gun violence is more complicated than most people assume.

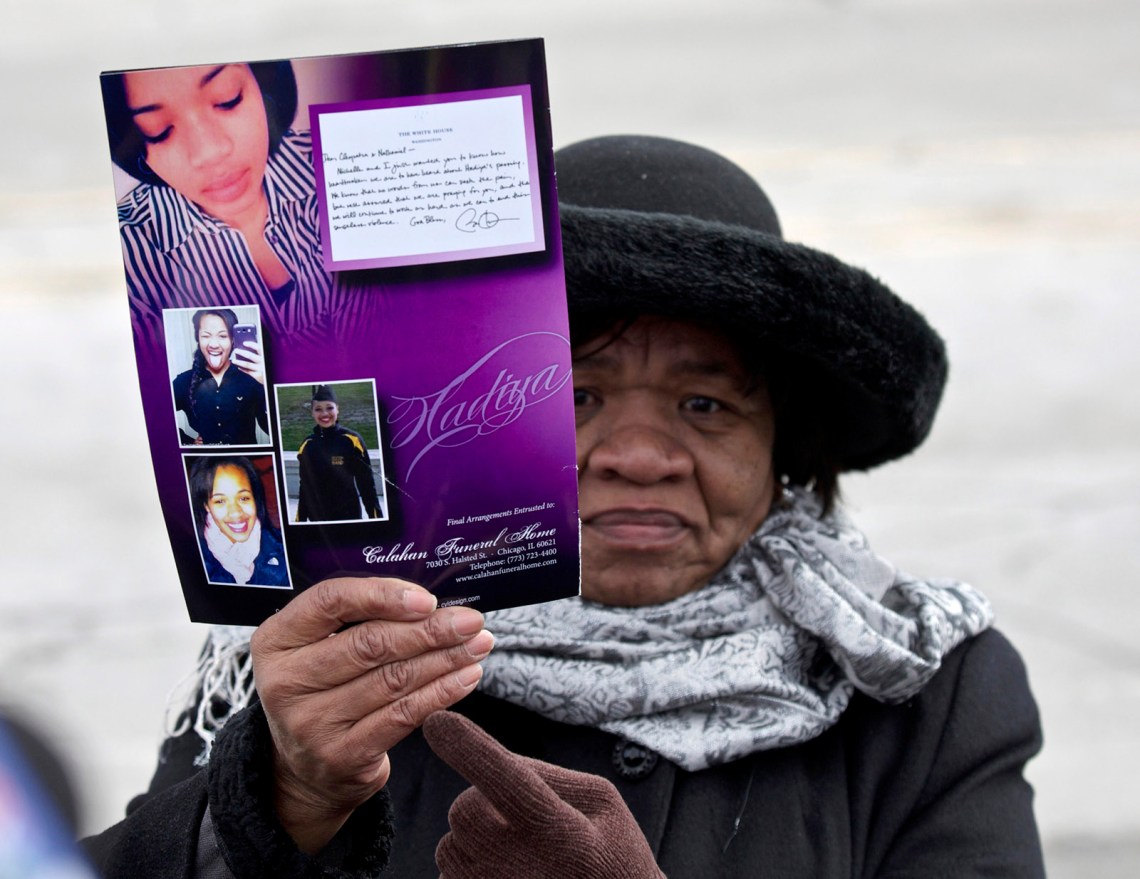

In January 2013 Hadiya Pendleton, a fifteen-year-old high school student, was hanging out in a Chicago park with friends after finishing her final exams when a young man, eighteen years old, who was affiliated with a gang mistook them for rival gang members and opened fire. Two of Pendleton’s friends were wounded, and she was fatally shot in the back. Most individual shootings go unnoticed, but hers made national news, perhaps because the week before her death she had twirled batons with her high school band at President Barack Obama’s second inauguration. Killed only a mile from Obama’s house, she became a symbol of Chicago’s notorious gun violence.

The response to Pendleton’s death split along predictable political lines, as Kotlowitz, a former Wall Street Journal reporter and a longtime chronicler of Chicago’s urban violence and poverty, recounts in An American Summer. Illinois Republican senator Mark Kirk told a television reporter, “My top priority is to arrest the Gangster Disciple gang, which is eighteen thousand people. I would like to do a mass pickup of them and put them all in the Thomson Correctional Facility.” This statement infuriated longtime representative Bobby Rush, who called Kirk’s plan “an upper-middle-class, elitist, white boy solution to a problem he knows nothing about.” “Kirk believed that the violence was a police problem,” writes Kotlowitz. “Rush believed it was a problem growing from the economic distress and physical isolation of his community.” Though both sides agree that the issue of violent crime must be addressed, this debate has been going on for decades, with conservatives calling for law and order and liberals emphasizing the need to address root causes.

An American Summer opens with a Chicago Sun-Times headline from 2006: “Murder at a Good Address.” The story, Kotlowitz recalls, “reported on a dermatologist who was discovered bound and brutally stabbed in his office on luxurious Michigan Avenue.” What struck Kotlowitz, though, was “the brazenness and honesty” of the headline—the assumption that newspaper readers are more interested in stories of privileged lives interrupted by shocking violence than in the shocking violence that is almost quotidian in the lives of some of the city’s poorest residents. In his book, he seeks to redress this bias.

Kotlowitz sets out to capture the summer of 2013 in Chicago, a summer chosen at random (and one that turned out to be less violent than most). He speaks to a remarkable variety of people in the city’s most abandoned communities, including Marcello, a scholarship student at a prep school who commits a slew of violent robberies with friends from his neighborhood; Mike Kelly, a hard-charging Irish-American realtor who adopts an African-American teenager to the horror of his racist family; and Eddie Bocanegra, the founder of a support group for bereaved mothers who confesses to one of them that he served fourteen years for murdering a rival gang member. The most shocking murder at a bad address, however, is the shooting of nineteen-year-old Calvin Cross by police after he allegedly fidgeted with his waistband. (Two officers later claimed Cross shot at them. No evidence to support that account was found at the crime scene, and the city later settled with Cross’s family for $2 million.) But Kotlowitz doesn’t just want to log one summer’s worth of violence; he’s interested in excavating the legacy of racism and violence, in tracing cause and effect.

Advertisement

Kotlowitz’s best dispatches bring the reader close to the human experience of violence and its penumbra of meaninglessness. A social worker named Anita picks Thomas out of a freshman algebra class because he’s pacing at the back of the room muttering Motherfucker, Motherfucker over and over. Of the many challenges Thomas faces—his mother struggles with drug addiction, and he lives with his grandmother in an especially dangerous part of Englewood, a neighborhood on the city’s South Side—the main one is PTSD: he keeps witnessing shootings. At the surprise birthday party of his eleven-year-old friend Nugget, a stray bullet from the street hit the birthday girl in the head, “her brain matter oozing out of her skull and onto her braids.” And “during [his] high school years,” Kotlowitz writes, “the stories just kept coming”:

Thomas was like the Zelig of Englewood’s violence. There was Nugget. And the time he saw a boy shot in the face in a nearby park. And his friend who was shot in the leg. And his brother [paralyzed from the waist down by a bullet]. And coming upon two men who’d been shot and killed still sitting in their car, one of them with his head leaning out the window as if he were trying to get some air.

One day, during the course of Kotlowitz’s reporting, Thomas is sitting on the porch with his paralyzed brother and his best friend, Shakaki, when a teenager from the neighborhood’s rival clique comes running out of a nearby alley and starts shooting. Thomas’s brother only realizes he’s been shot in the knee when he sees the blood pooling at his feet. Shakaki, hit in the stomach, dies eight hours later. Immediately after the shooting, Thomas gets a gun—from whom he won’t say—and stalks around a nearby gas station, hoping to find someone from the shooter’s crew. No one arrives. In the days following, Thomas can’t sleep. He smokes weed, watches mindless TV, but nothing brings him peace. Then an older boy pushes Thomas’s six-year-old cousin to the ground, which offers him the release he needs. He punches the boy so hard that a tooth breaks off and embeds in his fist. The street gets the story wrong: rumor has it that that punch was the reason for the shooting, when it was the reaction. Finally, Thomas can sleep.

Where will you be in ten years? Kotlowitz asks Thomas. “Might be in jail,” he says. “Because I think I’m gonna hurt someone.” Thomas tells Anita, the social worker, that he thinks he might kill somebody. “She realized,” Kotlowitz writes,

in this moment that Thomas was trying as best he could to be honest about some feelings he had, feelings that scared him…. Anita realized that he was telling her that if he could hurt someone, he might feel better, that maybe some of the pain would go away, even just temporarily. He knew this because it had worked before.

Kotlowitz’s account is moving, but what are we moved to do about it? Like other journalists with ethnographic approaches, he has been criticized for not offering solutions since his first—and best—book, There Are No Children Here (1991), a poignant, novelistic portrait of the challenges of growing up poor and black in the Chicago projects.2 Decades later, Kotlowitz’s only rebuttal to those who demand solutions is: “What to make of all this? I don’t know that I fully know myself.”

Thomas Abt has some ideas. Abt is a senior fellow at the Council on Criminal Justice and the director of its National Commission on Covid-19 and Criminal Justice. He was formerly a prosecutor who worked on reducing urban violence under President Obama and New York governor Andrew Cuomo. His book, Bleeding Out, is a manifesto for targeting violence first and foremost. It’s not the most important problem, Abt writes, just the one that needs to be addressed before we can take on problems that may lead people to violence, such as economic, educational, and racial inequality. If you’re not safe, nothing else matters.

Advertisement

According to Patrick Sharkey’s research, more than half of urban youth who have been exposed to violence suffer from PTSD; it is one of the most significant factors in how children growing up in distressed areas will fare in adulthood. You can’t study if you’re constantly on the lookout for stray bullets; you can’t keep a job if you have to care for your wounded brother (facts made abundantly clear throughout Kotlowitz’s decades of reporting).

Moreover, violence sucks up a tremendous amount of money. According to three frequently cited peer-reviewed studies, every murder costs society anywhere from $10 million to $19.2 million in lost labor, property damage, medical costs, judicial costs, and diminished quality of life and economic activity, because fearful citizens avoid certain activities. That’s between $531 and $1,020 per American, paid out in higher taxes, higher insurance premiums, and lower property values. Abt cites studies showing that for every public dollar spent on reducing fatal violence, $135 would be saved.

Abt’s approach doesn’t look anything like the mass arrests advocated by Senator Kirk. Cities, he says, should focus their limited resources and attention not on crime generally but on violence specifically. They should zero in on particular places where crime is concentrated—a dangerous street corner, an abandoned house—not on entire neighborhoods, which is stigmatizing, demoralizing, and inefficient; such wider policing also delegitimizes the police in the eyes of the community, as Black Lives Matter protests over the last seven years have made clear. Law enforcement, Abt believes, must work to restore trust by fixing the imbalance of overpolicing and underprotecting. Young black men are disproportionately targeted by police, stopped for minor offenses like a broken taillight. Fifty-two percent of homicides are of black people, even though they make up only 13 percent of the population. And in recent years the number of homicides that police solve has been stalled at around 60 percent: kill someone and the odds are four out of ten, Abt says, that you’ll get away with murder. According to other studies, in poor communities of color the odds are sometimes as high as eight out of ten.

Consider Ferguson, Missouri, where Michael Brown was shot and killed by a police officer in 2014. Black people made up 67 percent of the population but accounted for 90 percent of police citations. The primary objective of the local courts, federal reports documented, was not justice but compelling payment of fees and fines to meet city revenue demands. Minor offenses like a parking violation, Abt writes, “morphed into crippling debts resulting in lost licenses, jobs, and housing, and even jail time”:

In one case, an African American woman illegally parked her car and received two citations along with a fine for $151. The woman, poor and occasionally homeless, struggled to pay. Over the next seven years, she was charged seven times for failure to pay and to appear, spent six days in jail, was arrested twice, and paid $550, all because she parked illegally once.

This maddening scenario, in which a parking ticket can become a lifelong albatross, destroys trust in law enforcement, if less obviously than the murder of an unarmed black man does.

In the year after Brown’s shooting, violent crime in Ferguson increased by 65 percent; homicides increased by 150 percent. Conservatives attributed this to criminals being emboldened by criticism of the police by protesters and the media. St. Louis police chief Sam Dotson gave that argument his own Trumpian moniker: “It’s the Ferguson effect,” he said.

But the real Ferguson effect, Abt argues, is a community’s violent response when an act of police brutality proves both that the law doesn’t keep people safe and that it isn’t fair—neither neutral, proportional, transparent, nor equal. When protests erupted in 2015 after Freddie Gray’s spine snapped in the back of a police van, Baltimore police (under the direction of the police union, it’s believed) responded with retaliatory pullbacks of officers, jeopardizing the very communities that needed protection most and offering an opening—an invitation, really—to the violent fringe. (The same revenge tactics have been documented in cities from LA to Minneapolis that considered police budget cuts. “The first time I cut money from the proposed police budget, I had an uptick in calls taking forever to get a response,” Steve Fletcher, a Minneapolis councilman, recently tweeted, “and MPD officers telling business owners to call their councilman about why it took so long.”) The year of Gray’s death, Baltimore counted 342 murders, an increase of 62 percent over the year before and near the all-time high in the 1990s.

Abt’s strength is in debunking the misleading narratives that calcify around issues of public safety. Gangs are a good example. There’s a misconception that they are highly structured and cohesive, with a strong sense of purpose and clear leadership. Yet most gangs in the US, as Representative Rush stated and Abt confirms, “are small, informal groups that have limited capacity for highly organized crime.” They form in neglected and impoverished communities, mainly in response to other gangs.

Then there’s what Abt calls “our national preoccupation with mass shootings,” in which four or more people are killed, usually by a lone gunman. Approximately 1,322 people have been killed in mass shootings since what’s considered the first one in the US: the Texas Tower massacre on the University of Texas at Austin campus in 1966. Over that same time, more than a million people have been killed by ordinary gun violence. “When mass shootings dominate the conversation, the policy discussion on gun violence is perverted,” Abt argues. While 75 percent of mass shootings are committed with legal firearms, for instance, the overwhelming majority of urban homicides are not. “In terms of probability,” Abt writes,

a typical school will see a student homicide only once every six thousand years. Billions have been spent on measures to make schools more secure, despite the fact that there is no evidence that they significantly reduce the risk of school shootings.

Abt would reapportion that money to address the violence that strikes day after day. In cities with high homicide rates, he suggests that funding be allotted at a rate of $30,000 per homicide per year—an amount that generally averages to less than one half of one percent of a city’s annual budget. The violence-reduction strategy he recommends—the one he found most effective in a meta-review of more than forty studies—is “focused deterrence,” which attempts to identify those at risk of committing violence. After securing that person in a safe location and guarding him against harm or retaliation, a meeting is arranged between the individual at risk of comitting violence and three others: a social worker, a community member, and a law enforcement official, who together attempt to prevent the violence from occurring and emphasize possible consequences. The social worker is intended to put the person on a stable footing by addressing immediate needs such as food and shelter. The community member—the most effective tend to be mothers of those killed by violence—is there to lend legitimacy, something the cops, who have often lost the community’s trust, can’t provide.

Focused deterrence only works if it doesn’t mire participants in long waits, lots of paperwork, and other hurdles. To that end, Abt calls for reimagining the job of social worker:

Like law enforcement, they must work in shifts in order to be available at all hours, they must have adequate communication and transportation that allow them to respond quickly, and they must have access to resources that can be deployed instantly in order to remedy a dangerous situation.

If, in order to head off a homicide, it becomes necessary to respond to the house of a would-be shooter at 3 AM, drive that individual to a bus station, and then buy them a ticket to get them temporarily out of town, then that is what task force members must be able to do.

Implicit in this suggestion is expanded financial support for social services (the problem has long been a lack of funding, not imagination). In Bleeding Out, Abt calls for $899 million in federal money to be spent over eight years on anti–gun violence programs—“the absolute most I believed was politically possible at the time [June 2019],” he recently tweeted. While campaigning for the presidency, Joe Biden adopted Abt’s proposal to spend $900 million on anti–gun violence measures, and after his election he invited local antiviolence advocates to join his transition team and build on Abt’s idea. Tucked into Biden’s $2.1 trillion infrastructure plan, the American Jobs Act, is a pledge of $5.3 billion for evidence-based community violence prevention programs over eight years. “This. Is. Remarkable,” Thomas Abt tweeted. “I estimated that $899 million—properly spent—could save 12,132 lives over 8 years. This new proposal is 5 TIMES as big, so we could be looking at a MUCH larger impact.”

The things such money might fund include focused deterrence, violence interruption (in which someone with credibility or a relevant personal history attempts to mediate disputes before they become violent), and cognitive behavioral therapy. In another tweet, Abt wrote, “Let’s give credit where it’s due: this proposal is the direct result of advocacy by the #FUNDPEACE movement—a coalition of Black and Brown-led organizations.” Of course, this is just a proposal, and unlikely to squeeze past Senate Republicans, who have already griped that Biden’s infrastructure bill includes funding for too many noninfrastructure programs. Nevertheless, it sets a new standard for what’s reasonable.

Because Abt’s book was written before George Floyd’s death, it doesn’t consider another newly “reasonable” idea: disbanding the police altogether. This possibility, which seemed inconceivably radical just a year ago, gained traction when the Minneapolis city council voted to dismantle its police department (the culture of which was deemed irreparable). It hasn’t been disbanded yet—city council members and advocates are trying to get community support for replacing the police department with a department for public safety—and it may never be. But such a vote was possible because academics and advocates had already laid the groundwork: How can anyone expect police, who are promoted based on their arrest rates, to deliver a message of caring and consequences? Even moves toward community policing, which encourages officers to develop positive relationships with local agencies and members of the public, can’t mitigate the imbalance of power or change an ossified cop culture.

In The End of Policing (2017), the Brooklyn College sociologist Alex S. Vitale makes a persuasive argument for abolishing the police, describing how police departments originated not to fight crime or keep society safe but to protect the propertied classes from disorder and labor uprisings. Most police officers make no more than one felony arrest a year. The majority of their work is taking reports, engaging in random patrols, addressing motor vehicle violations and noise complaints, issuing tickets, and making misdemeanor arrests for public drinking and drug possession. “There is an issue of substantive justice here,” Vitale writes. “Even if the law is enforced equitably and without bail or malice, it still results in the incarceration of large numbers of people who are homeless, mentally ill, and poor, rather than hardened predators.”

What if social problems were met not with punishment but with their obvious solutions—mental illness with counseling, homelessness with housing, poverty with an increased minimum wage or other forms of monetary support, like a universal basic income? A new authority could be established solely to address violent crime with detective work and focused deterrence.

Despite Abt’s optimistic—some might say idealistic—suggestions for reform, as a former prosecutor he supports the current criminal justice system. He believes in prisons and thinks that more perpetrators of violent crime should be convicted and locked away. “Increasing the certainty of punishment,” he writes,

produces a stronger deterrent effect…. If a murderer is caught the first time they kill, they will be incarcerated and unable to kill again as long as they remain in prison…. Bringing murderers to justice eliminates the need and opportunity for others to take revenge.

(Sociologists, however, generally agree that the threat of prison doesn’t deter crime. Prisons often teach juveniles to become criminals. In many states, up to 80 percent will be rearrested within three years of release.)

Accountability is important, but is prison the most effective long-term strategy? As Danielle Sered argues in her powerful book on violent crime, Until We Reckon (2019), prison

intensifies [the drivers of violence], interrupting people’s education, rendering many homeless upon return from jail or prison, limiting their prospects for employment and a living wage, and disrupting the social fabric that is the strongest protection against harm, even in the face of poverty.

While Abt acknowledges the problem of overincarceration in the US, his book would be stronger had he grappled with some alternatives. Sered advocates for restorative justice, a mediated process whereby survivors help determine how to hold their aggressors accountable, often meeting with them in the process. According to her, 90 percent of survivors invited to participate in her Brooklyn-based restorative justice program, Common Justice, accepted, and fewer than 6 percent of defendants have left the program because they were convicted of a new crime. As Michelle Kuo underlined in her review of Sered in these pages, a 2007 study analyzing thirty-six studies from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the UK, and the US found that restorative justice significantly reduced survivors’ post-traumatic stress symptoms and desire for revenge.3 It also reduced recidivism among both adult and youth offenders. The premise of restorative justice seems not unlike some of Abt’s focused-deterrence strategies. Why not continue to support people after they have made a mistake?

The great disadvantage of Abt’s approach is that, for all his evidence-based recommendations, his book doesn’t take into account how much he’s asking of people who aren’t adequately supported or protected—namely witnesses. Perhaps that is why the focused-deterrence program he implemented in Buffalo in 2013, Gun Involved Violence Elimination, has been a mixed success, resulting in a rise in gun violence followed by a decline. If interventions fail, Abt’s strategy relies on the criminal justice system to hold aggressors accountable, and the criminal justice system relies on witnesses who aren’t protected afterward.

Kotlowitz captures this conundrum when writing about Jose, a teenager who spent three weeks in an induced coma after a bullet pierced his mouth, exited his jaw, and blew out his right cheekbone:

He needed extensive reconstructive surgery. Jose knew his assailant, but his assailant’s friends sent him text messages offering to pay him not to testify. In court the assailant’s friends muttered loud enough for him to hear, You fuckin’ trick…. Jose’s mother, it turns out, works as a victim’s advocate in juvenile court. Her job is to offer reassurance and encouragement to victims as they wait to testify, but she couldn’t or wouldn’t insist that her son testify. In fact, she told him not to. “What guarantee would there be to protect him?” she asked rhetorically. “I love my work. The attorneys here will tell you that I can bring in anyone in the world.” She paused. “Except my son.”

On the stand, Jose is asked question after question. The only answer he offers, again and again, is one that tends to haunt books on urban violence: I don’t know.

—May 13, 2021

This Issue

June 10, 2021

Far from the Realm of the Real

The King of Little England

-

1

According to the 2019 annual FBI report covering more than 18,500 jurisdictions around the country, the violent crime rate fell 49 percent between 1993 and 2019. Based on data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which compiles survey responses from approximately 160,000 Americans on whether they were victims of crime, the rate fell 74 percent. Significantly, as the Pew Research Center noted in November 2020, public perceptions about crime in the US often don’t align with the data: “In 20 of 24 Gallup surveys conducted since 1993, at least 60% of US adults have said there is more crime nationally than there was the year before, despite the generally downward trend in national violent and property crime rates during most of that period.” ↩

-

2

“There Are No Children Here (1991) is an eloquent record of what it’s like to grow up poor, young, and black in a large American city,” Michael Massing wrote in these pages (“The Welfare Blues,” March 24, 1994), “but it has nothing to say about possible solutions. It is frustrating to read his moving account without hearing his thoughts on its implications.” ↩

-

3

“What Replaces Prisons?,” The New York Review, August 20, 2020. ↩