In 1890 Lafcadio Hearn arrived in Japan on a reporting assignment for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. Just shy of forty years old, he was a popular journalist and novelist, his work marked by a hatred of modern industrial life and a fascination with what he called “survivals”—traditions or folktales that he hoped would provide a living link to a more ancient form of narrative. In Cincinnati, he had written about the music of the black community that lived on the city’s riverfront; in New Orleans, about the songs, food, and folkways of the Creole population (including a book that contains the first published recipe for gumbo). “The pattern of Hearn’s life,” Christopher Benfey wrote, “was to arrive in a place just as what he loved there was on the point of disappearing.”

Japan, which had only recently emerged from over two centuries of relative isolation, should have been a dream assignment. But not long after making port in Yokohama, Hearn decided to cut ties with Harper’s, and did so in a series of letters—some of them addressed to Henry Harper himself—in which he railed against seemingly everyone he had interacted with at the company:

Lying clerks and hypocritical, thieving editors, and artists whose artistic ability consists in farting sixty-seven times to the minute—scallywags, scoundrels, swindlers, sons of bitches—

Pisspots-with-the-handles-broken-off-and-the-bottom-knocked-out—ignoramuses with the souls of slime composed of seventeen different kinds of shit.

He went on a while longer (“you miserable beggarly buggerly cowardly rascally boorish brutal sons of bitches”) before a final scatological flourish: “Please understand that your resentment has for me less than the value of a bottled fart, and your bank-account less consequence than a wooden shithouse struck by lightning.”

What exactly prompted all this is hard to say. That he believed his treatment by Harper’s to have been beneath his dignity is clear. But there is little evidence to suggest that this was so, and after twenty years eking out a living in the literary industry, he may simply have been at the end of his rope, a situation not helped by his general irascibility and lifelong inclination to the abrupt, scorched-earth termination of friendships. (One former friend, asked to return a pair of shoes, replied simply, “Dear Hearn: You can go to Japan or you can go to hell.”)

Whatever the case, were it not for this letter, we might well not have any of the books under review. Having severed his sole source of income in a country in which he knew nearly no one and whose language he was unable to read or speak, Hearn—blind in one eye and severely myopic in the other—was forced to find a job. That search, in turn, led him to a remote corner of Japan, where he became a schoolteacher, eventually marrying into a former samurai family. He spent the rest of his life in Japan, practicing Buddhism, becoming a citizen, and establishing himself as the Anglophone world’s foremost interpreter of Japanese culture and myth—all without ever really learning the language.

There is much about him that hasn’t aged well. He was an exoticizer extraordinaire—an admirer of Pierre Loti, a devotee of Herbert Spencer’s theories of social Darwinism—and tended to fixate wherever he went on the antiquated and the bizarre, eschewing what struck him as modern. Nor has his posthumous standing been helped by his prose style, which often reads like H.P. Lovecraft avant la lettre. (“The air is foul with the breath of nameless narrow alleys; and the more distant lights seem to own a phosphorescent glow suggesting foul miasmal exhalation and ancient decay,” he once wrote of a foggy street in Cincinnati.)1

Yet in Japan he pared his style back into something plainer and more direct, and produced a body of work that, nearly a hundred years after it was first translated into Japanese, is still read and admired there. In his nonfiction—essays, memoir, and travel writing—one can see how Hearn, at his best, captured the sights and sounds of traditional Japanese life at a moment when the country was rapidly transitioning to an industrial society. But most of all, the pleasures of his work are to be found in his delightfully bizarre hybrid renditions of Japanese folklore—particularly of a genre called kaidan, or tales of the uncanny—old stories that he blended with elements of horror and French Romanticism, the best of which are collected in Japanese Ghost Stories and Japanese Tales of Lafcadio Hearn, as well as a new edition of his book Kwaidan (the title is an antiquated transliteration of kaidan). The result is something that sits at the nexus of Borges, Baudelaire, and Bram Stoker, and that prompted Malcolm Cowley to call Hearn “the writer in our language who can best be compared with Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm.”

Advertisement

He was born Patrick Lafcadio Tessima Carlos Hearn on the Greek island of Lefkada, the second child of Rosa Cassimati, from Kythira, and an Anglo-Irish father, Charles Hearn, who served in the British army’s occupying force in the Ionian islands. After Hearn was brought back to Ireland, his parents disappeared in quick succession—Charles for work and another marriage, Rosa for Greece—leaving him to be raised by a widowed great-aunt, in whose house he read titillating gothic horrors like Matthew Lewis’s The Monk and soaked up Irish myth and folktales. “I had a Connaught nurse who told me fairy-tales and ghost-stories,” he wrote to Yeats in 1901. “So I ought to love Irish Things, and do.”

In his teens, financial difficulties led to his withdrawal from boarding school, where an accident had left him with only one working eye, and after a spell in a garret in the East End of London, he was sent to Cincinnati to find a distant relation, who promptly turned him away. Hearn endured bouts of homelessness until he met Henry Watkin, an avuncular anarchist printer who allowed him to sleep in his shop on a heap of old newspapers. The two soon became friends, Watkin tutoring Hearn on the finer points of Fourierism and Hearn leaving him weird, plaintive notes:

I came to see you…GONE!!! Then I departed, wandering among the tombs of Memory, where the Ghouls of the Present gnaw the black bones of the Past. Then I returned and crept to the door and listened to see if I could hear the beating of your hideous heart.

Undeterred, Watkin encouraged Hearn to write, helping him make his way into the newspaper trade. Hearn had quick success, and by November 1874 he wrote an article for the Enquirer that seems to have scandalized the entire city of Cincinnati. The headline read:

VIOLENT CREMATION

SATURDAY NIGHT’S HORRIBLE CRIME

A MAN MURDERED AND BURNED IN A FURNACE

THE TERRIBLE VENGEANCE OF A FATHER…

THE PITIFUL TESTIMONY OF A TREMBLING HORSE

The article relayed, in a lurid account, the murder of a Westphalian immigrant named Herman Schilling, whose charred remains had been found in a furnace. Suspicion fell on a local bar owner, who had accused Schilling of seducing his fifteen-year-old daughter, thereby causing her to take her own life (“which charge,” Hearn wrote, “was denied by the accused, who, while admitting his criminal connection with the girl, alleged that he was not the first or only one so favored”). What was found of Schilling amounted to little more than “great shapeless lumps of half-burnt bituminous coal,” a skull that “had burst like a shell in the fierce furnace-heat,” and a brain that “had all boiled away, save a small wasted lump at the base of the skull about the size of a lemon,” the consistency of which, Hearn suggested, resembled “banana fruit.”

The story brought the struggling Enquirer into the black. It also cemented Hearn’s reputation as a journalist, and he continued to write, often under the sobriquet “Dismal Man,” articles that ranged from what Henry Luce might have classed as the “grue, sex, nonsense, and mugs” beat, to more gonzo features, including a profile of a professional steeple climber who hoisted a terrified Hearn behind him as he clambered to the top of a church, and, decades before Upton Sinclair, an article contrasting the horrifying practices of the city’s slaughterhouses with the far more humane methods of its kosher butcheries. He wrote often about the city’s black communities, and though some of these articles have a leering quality, others are more substantial. In one story, he profiled a former slave, Henrietta Wood, then in the midst of suing a man who in 1853, after she had been freed, kidnapped her and sold her back into slavery. In 1878, two years after the article was published, Wood won the case, receiving $2,500—an amount that remains the largest known sum ever awarded by a US court in restitution for slavery.2

Hearn left Cincinnati not long after meeting his first wife, Mattie, who had been born into slavery. They married, in violation of anti-miscegenation laws, and when the Enquirer found out, Hearn was fired. Though he found work at another paper, the relentless pace of industrial Cincinnati had begun to wear on him, and in 1877 he relocated to New Orleans, leaving Mattie behind.

New Orleans in the aftermath of the Civil War was a city in decline. Smitten, Hearn described it as “deserted and half in ruins…a dead bride crowned with orange flowers.” His reputation grew in these years, as he published articles, editorials, feuilletons, and translations of Gautier, Flaubert, Maupassant, and Zola. He came to national attention for an account of a previously unknown lacustrine village in the southern swamplands of Louisiana, where fishermen and alligator hunters from the Philippines lived in houses “poised upon slender supports above the marsh, like cranes or bitterns watching for scaly prey.”

Advertisement

He also wrote much about the city’s Creole culture, including La Cuisine Creole: A Collection of Culinary Recipes and Gombo Zhèbes: A Little Dictionary of Creole Proverbs, Selected from Six Creole Dialects (both from 1885). Longing as ever for bygone ways of life, he was especially drawn to the descendants of the French and Spanish settlers who had ruled colonial Louisiana:

Without, roared the Iron Age, the angry waves of American traffic; within, one heard only the murmur of the languid fountain, the sound of deeply musical voices conversing in the languages of Paris and Madrid, the playful chatter of dark-haired children lisping in sweet and many-voweled Creole, and through it all, the soft, caressing coo of doves. Without, it was the year 1879; within, it was the epoch of the Spanish Domination.

But while he had hoped New Orleans would provide an antidote to the modern life of Cincinnati, he found there too that “the somnolent quiet of the old streets is being already broken by the energetic bustle of American commerce.” He traveled next to the French West Indies, “an idealized tropicalized glorified old New Orleans,” before it disappointed him in turn. His interest in Japan was piqued in part by an exhibit at the New Orleans Cotton Centennial Exhibition, where, in spite of the emphasis on Japan’s industrial advancements, Hearn found himself drawn to “the antique art of Nippon.”

Hearn arrived in Japan toward the end of an influx of American artists, writers, and intellectuals who had begun streaming east after the start of the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Though Hearn himself was hardly free of prejudice (“Elfish everything seems; for everything as well as everybody is small, queer, and mysterious”), he was on the whole far more perceptive and sympathetic than his contemporaries, among whom were Percival Lowell, who said the Japanese were a nation of imitators; John La Farge, who in his “Essay on Japanese Art” (1870) wondered whether “the Japanese have an ideal”; and Basil Hall Chamberlain, a professor of Japanese at Tokyo University, of whose book Things Japanese a former pupil said that “were it reprinted in Japanese, his life could not be guaranteed twelve hours.”

It was through Chamberlain’s intercession that Hearn secured his teaching job in the town of Matsue, on the southwest coast of the main island of Honshu. Once he had settled, he was introduced to his second wife, Setsuko Koizumi, by a colleague. He was happiest here, where old ways of life had changed the least, and, as in New Orleans and the French West Indies, he again wrote sketches and scenes. In “The Chief City of the Province of the Gods,” one of the loveliest of Hearn’s Japanese sketches, he describes, over the course of a day, the sights and sounds of Matsue circa 1890, from waking to the rhythmic thud of rice being milled in a giant mortar to the clapping that accompanied morning prayers and the clattering of wooden sandals over a bridge. Toward night he returns home, stopping on a bridge overlooking a misty river:

And I become suddenly aware that little white things are fluttering slowly down into it from the fingers of a woman standing upon the bridge beside me, and murmuring something in a low sweet voice. She is praying for her dead child. Each of those little papers she is dropping into the current bears a tiny picture of Jizo [the guardian deity of children], and perhaps a little inscription.

But just as it had in Cincinnati, New Orleans, and the French West Indies, the shine eventually came off. Over the years, Hearn and Setsu, to his dismay and her delight, moved from the rural idyll of Matsue to more urbane and industrialized cities, Hearn griping all the way. There was Kumamoto (“You wonder why I hate Kumamoto. Well, firstly, because it is modernized. And then I hate it because it is too big, and has no temples and priests and curious customs in it. Thirdly, I hate it because it is ugly”), and the open-port city of Kobe, which he liked well enough except for its profusion of English and Americans (“Carpets—dirty shoes—absurd fashions—wickedly expensive living—airs—vanities—gossip: how much sweeter the Japanese life”). Later, they moved to Tokyo (“the most horrible place in Japan”), where he taught English literature at Tokyo University.

Hearn, who missed Matsue, wrote roughly a book a year, including Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894), Kokoro: Hints and Echoes of Japanese Inner Life (1896), and In Ghostly Japan (1899). His writings at first drew lightly on old Japanese folk tales and ghost stories, often touching on them in his travel sketches, as in “The Dream of a Summer Day,” from his 1895 book Out of the East, in which the name of his hotel, the House of Urashima, prompts him to tell of the eponymous fisherman, Urashima, a Rip van Winkle–like figure. In the final years of his life, however, Hearn and Setsu settled in a traditional house in a suburb of Tokyo, and he turned his focus more and more to these tales, until finally, with Kwaidan (1904), perhaps his best book, they became the centerpiece.

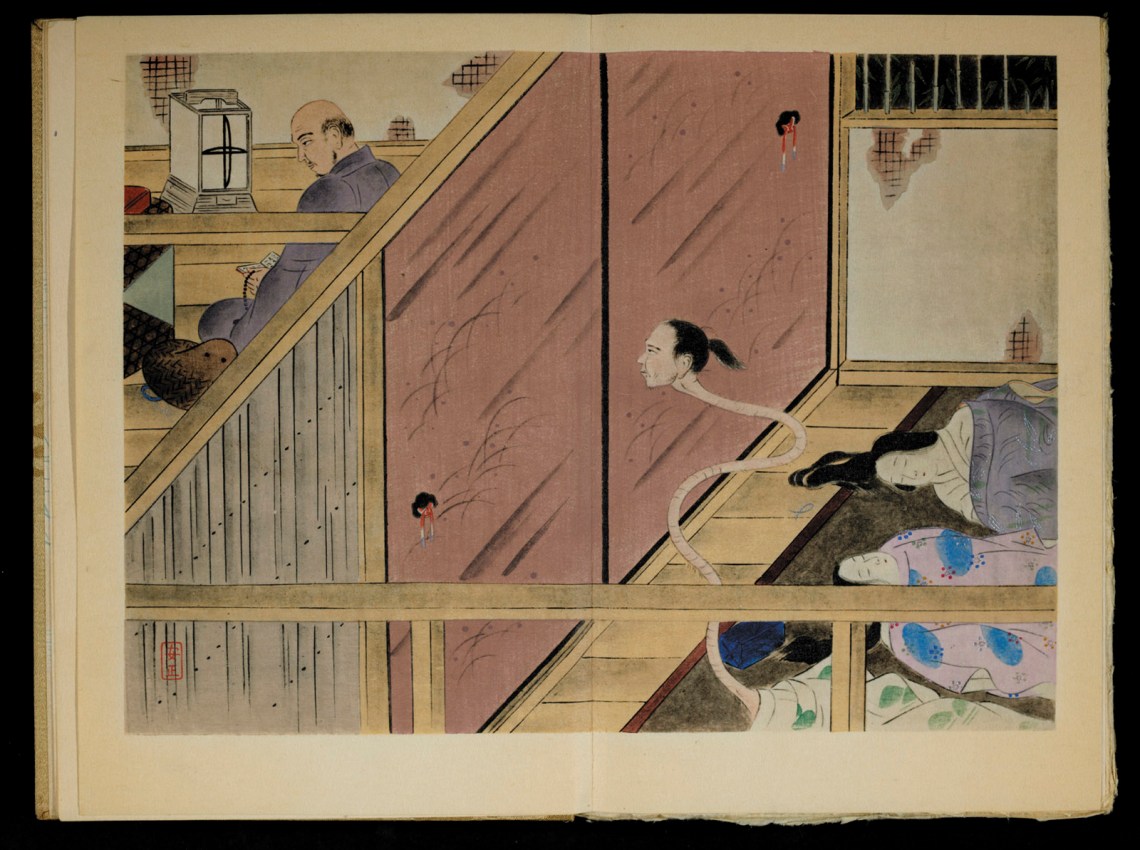

Kaidan—the literary genre of ghost stories or tales of the weird—was an oral tradition, derived partly from seventeenth-century events during which people would gather around a paper lamp filled with a hundred wicks, removing a wick each time a story was told and hoping, by the end, to induce a supernatural event. Though these stories drew variously from Chinese fiction, Buddhist teachings, and Japanese folk tales, and could have moral or religious implications, just as often, the scholar Noriko Reider writes, “the appeal fundamentally lies in how strange things can be.” One such story told of a thirty-two-year-old monk with an itchy penis, who, after applying a compress many times, watched as the organ, along with his scrotum, fell off: “I picked them up and looked at them. But as I found them useless, I threw them away. After that, a vulva formed, just like that of an ordinary woman. I then married and had two children.”

Hearn collected these stories voraciously, sometimes paying young students to produce literal English translations of manuscripts, other times gleaning them from people he happened to meet. But one of his main sources was Setsu, who hunted for texts in secondhand bookstores and helped him assimilate the material. On dreary nights she would lower the lamp’s wick and recite the tales to him. “Since he looked as if he were really frightened while listening to me,” she wrote in her memoir, “my narrative increasingly took on a life of its own. On those occasions, my house seemed as if it were haunted, and I sometimes had horrible dreams and came to be afflicted with nightmares.” If Hearn liked the story, he would write it down, asking her to repeat it several times, always as if it were her own, quizzing her about various details.

His retellings of these strange tales are a delight to read, not least because they reflect his shift late in life to a less ornamented prose style. “The great point is to touch with simple words,” he wrote to Chamberlain. It is evident from the first sentence of “The Corpse-Rider”: “The body was cold as ice; the heart had long ceased to beat: yet there were no other signs of death.” Many of these tales, like “Rokuro-Kubi,” the story of a wandering monk named Kwairyo who happens upon a remote cabin in the mountains, have elements of horror and suspense. Kwairyo’s genteel hosts, whom he at first takes for displaced nobility, are revealed to be demons whose heads detach at night and, with long contrails, swim about in the air in search of human flesh.

Others are more surreal. In “The Dream of Akinosuke,” a man drinking with friends in the shade of a cedar tree finds himself compelled to take a nap and dreams of being called to an elaborate capital city to marry the daughter of the emperor. After a long life together, she dies, and when he wakes, he begins excavating an ant nest that he finds underfoot, unearthing a colony whose “tiny constructions of straw, clay, and stems bore an odd resemblance to miniature towns.” He begins to recognize places familiar from his dream and sees at the center of one of these miniature towns an ant whom he recognizes as the emperor, until finally, underneath “a tiny mound, on the top of which was fixed a water-worn pebble, in shape resembling a Buddhist monument,” he finds his wife, “embedded in clay—the dead body of a female ant.”

Perhaps the best and best known of the tales from Kwaidan—and, according to Setsu, one of Hearn’s favorites—is “The Story of Mimi-Nashi-Hoichi” (Hoichi the Earless), about a blind biwa3 player famous for his musical recitation of the epic history of the Heike and the Genji, two rival clans fighting for control of twelfth-century Japan. “Mimi-Nashi-Hoichi” opens with a brief account of the final battle between the clans—the Battle of Dan-no-ura, one of the most significant in Japanese history—in which “the Heike perished utterly, with their women and children, and their infant emperor likewise.” The sea and shore at Dan-no-ura, we’re told, have been haunted since. Hearn interrupts, addressing the reader:

Elsewhere I told you about the strange crabs found there, called Heike crabs, which have human faces on their backs, and are said to be the spirits of the Heike warriors. But there are many strange things to be seen and heard along that coast. On dark nights thousands of ghostly fires hover about the beach, or flit above the waves—pale lights which the fishermen call Oni-bi, or demon-fires; and, whenever the winds are up, a sound of great shouting comes from that sea, like a clamor of battle.

The story picks up some centuries after the battle, as Hoichi, who lives in a temple built to appease those spirits, is resting on the veranda at night. A strange samurai calls to him, telling Hoichi that he has been summoned to perform for the samurai’s lord, a person of exceedingly high rank who is traveling incognito. Led to the court, Hoichi hears

sounds of feet hurrying, and screens sliding, and rain-doors opening, and voices of women in converse. By the language of the women Hoichi knew them to be domestics in some noble household; but he could not imagine to what place he had been conducted.

The nobles show a conspicuous interest in the history of the Heike and ultimately request the recitation of the Battle of Dan-no-ura. Hoichi’s performance, which in the original Japanese text passes by in a summary sentence, is drawn out by Hearn:

Then Hoichi lifted up his voice, and chanted the chant of the fight on the bitter sea—wonderfully making his biwa to sound like the straining of oars and the rushing of ships, the whirr and the hissing of arrows, the shouting and trampling of men, the crashing of steel upon helmets, the plunging of slain in the flood. And to left and right of him, in the pauses of his playing, he could hear voices murmuring praise.

When he comes to the deaths of the Heike, Hoichi hears from the audience a “long shuddering cry of anguish; and thereafter they wept and wailed so loudly and so wildly that the blind man was frightened by the violence and grief that he had made.”

Meanwhile, the temple monks, suspicious about Hoichi’s absences, eventually find him alone in a graveyard, performing the Battle of Dan-no-ura in front of the tomb of the Heike’s child emperor, Antoku Tenno: “And behind him, and about him, and everywhere above the tombs, the fires of the dead were burning, like candles.” To free him from the revenants—who, the priest warns Hoichi, will tear him into pieces if they find him—the priest covers every inch of Hoichi’s body with the text of the Heart Sutra, which will render him invisible to the spirits. Though Hoichi survives and prospers, his epithet is a clue about which part of his body a feckless monk forgets to paint.

Hearn died in 1904, the year Kwaidan was published and the Russo-Japanese War began. By then his personal infatuation with the country had long since cooled (“What is there, finally, to love in Japan except what is passing away?”). But when his work began to make its way into Japanese translation in the 1920s, he was celebrated as the rare non-Japanese writer who had loved and understood the country, and his work in turn became part of Japanese literature (under his adopted name, Yakumo Koizumi). Hearn, like his idol Poe, was an object of great interest for Japan’s neo-gothic crime writers of the 1920s and 1930s, including Edogawa Rampo, one of the progenitors of the ero-guro-nansensu genre of the erotic grotesque. And in the years before World War II Hearn was an object of equal interest for the country’s nationalists, who saw in his veneration of Old Japan an implicit argument for Japan’s cultural superiority over the West. But his impact is perhaps easiest to see in Masaki Kobayashi’s film Kwaidan (1964), a retelling of four of Hearn’s stories that was, at the time of its making, the most expensive movie in Japanese history—filmed in an airplane hangar with hand-painted backdrops—and which became Kobayashi’s biggest box-office success.

Many have wondered why Kobayashi chose to make such a sumptuous adaptation of tales from Japanese folk traditions. His great films, after all—The Human Condition, Hara-Kiri—dealt with the brutality and hypocrisy of Japanese society, ancient and modern. Yet just as Hearn retold and interpreted these stories for a Western audience, Kobayashi in effect retranslated them himself: the film was, among much else, a concerted effort to reclaim elements of traditional Japanese aesthetics that had come to be seen as tainted by long association with wartime propaganda.

His rendition of “Mimi-Nashi-Hoichi” opens with a long set-piece of the Battle of Dan-no-ura enacted in the style of bunraku, traditional Japanese puppet theater, and drawing on the deliberate, ritualized movements of kabuki, with narration taking place in the form of a recitative and accompanied by the twang of an electrified biwa. As we watch the battle unfold from on high—the angle evocative of the perspective in emakimono, the illustrated hand scrolls that Kobayashi had studied under the art historian Yaichi Aizu (a former student of Hearn)—the slaughter builds to a climax, and the entire Heike clan, defeated, leaps one after another into the sea. Even as there is an otherworldly beauty to the scene, the violent end of the Heike is depicted starkly, free of nostalgia and romanticizing. Neither are the ghostly Heike whom Hoichi later encounters exemplars of a bygone chivalry: his mutilation, unlike in Hearn’s story, is shown in full, the samurai wrenching Hoichi about by the ears, leaving behind a grim scene for the monks to discover, the walls covered with handprints left in blood.

This Issue

June 10, 2021

How Can We Stop Gun Violence?

The King of Little England

-

1

In fact, Lovecraft was a fan: “Lafcadio Hearn, strange, wandering, and exotic, departs still farther from the realm of the real; and with the supreme artistry of a sensitive poet weaves phantasies impossible to an author of the solid roast-beef type.” ↩

-

2

Wood’s story was recently told by W. Caleb McDaniel in Sweet Taste of Liberty (Oxford University Press, 2019), which won the Pulitzer Prize for History. ↩

-

3

A short-necked lute, strummed with a plectrum. ↩