“‘It is finished’ can never be said of us,” Emily Dickinson once wrote, and certainly there is nothing finished about Emily Dickinson. Since her death in 1886, an army of poets, playwrights, biographers, filmmakers, cartoonists, editors, and literary gumshoes have celebrated her singular, heart-stopping poems while trying to decide what her intentions must have been and how we should read her.

It’s not easy. Without a definitive (“finished”) corpus of her work, she’s a perfect candidate for speculation, polemic, presumption, and fantasy. Famously she said that being published was “foreign to my thought, as Firmament to Fin.” As a result, only a handful of her poems were printed in her lifetime, at least one of them without her permission. In fact, Dickinson’s poems seem always to be in progress or in transit; she revised, reconsidered, and reconceived them, particularly when sending them to friends, as her very first editors would discover—and as editors keep discovering today. “Her true Flaubert was Penelope, to invert a famous allusion,” said the poet Richard Howard, “forever unraveling what she had figured on the loom the day before.” This is also what the critic Sharon Cameron suggested in her evocative (and well-titled) study Choosing Not Choosing (1993).

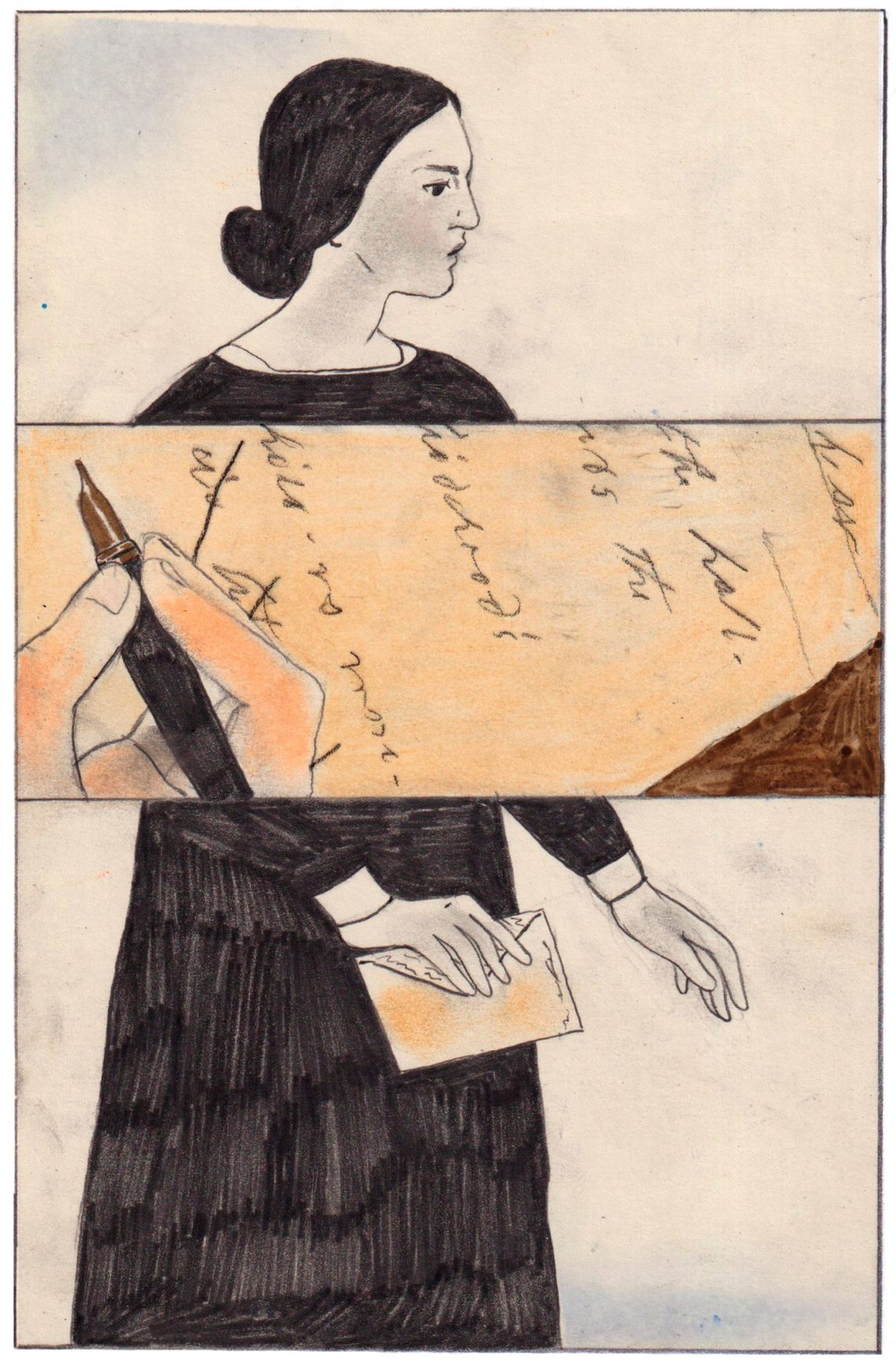

To Dickinson, then, it seems that literature was partly improvisation, much like her inventions at the piano, which were affectionately recalled by all who heard them. She toyed with several possibilities for an individual word while playing with image patterns, line arrangement, and metrics; she did not necessarily prefer one variation over another; she did not indicate when or if a poem was “finished.” What’s more, she frequently composed on snippets of paper—newspaper clippings, cut-up paper sacks—or around the edges of thin sheets, her cursive often illegible.

As a result, there’s a Dickinson for each season and almost every point of view. In the early part of the twentieth century, the poet Amy Lowell hailed her as a fellow traveler who “would set doors ajar and slam them.” In the 1930s literary sleuths feverishly hunted for the poet’s lost lover, as if she was the weird Miss Havisham of Amherst, Massachusetts. (“I do not cross my father’s ground to any House or town,” she once claimed.) By the 1950s, when scholars began to take serious notice, they christened Dickinson and Walt Whitman America’s greatest nineteenth-century poets, irrelevantly adding that she was “an unusually ineffective member of the weaker sex” (John Crowe Ransom) or a homebody spinster married to herself (R.P. Blackmur). The critic Richard Chase, also an enthusiast, was trying to be sympathetic, I guess, when he said that “one of the careers open to women was perpetual childhood.”

By the 1960s she was a pop cultural icon, a female poet for the dispirited female, as Simon and Garfunkel crooned in “The Dangling Conversation.” Billy Collins drolly disrobed her in the poem “Taking Off Emily Dickinson’s Clothes” (1998), and Terence Davies, in his film A Quiet Passion (2016), dressed her again as the nineteenth-century semi-hysteric whom he consigned eventually, and unquietly, to bed. Mercifully, in the hilarious short story “EDickinsonRepliLuxe” (2006) Joyce Carol Oates wryly satirized all such attempts at possessing the poet when she cast Dickinson as a computerized replicant, suitable for purchase, who speaks in riddles when she speaks at all. Alas, she’s ultimately assaulted by her frustrated owner. There’s a lesson here: Dickinson is the elusive poet par excellence, and we’re the assaulters.

For as Adrienne Rich first noticed, an utterly self-confident Dickinson is supremely herself, converting the gnarled xenophobia of New England and the languor of Romanticism into metaphors that scalp the soul:

I’m ceded—I’ve stopped being Their’s—

The name They dropped upon my face

With water, in the country church

Is finished using, now,

And They can put it with my Dolls,

My childhood, and the string of spools,

I’ve finished threading—too—

Baptized before, without the choice,

But this time, consciously, Of Grace—

Unto supremest name—

Called to my Full—The Crescent dropped—

Existence’s whole Arc, filled up,

With one—small Diadem—

My second Rank—too small the first—

Crowned—Crowing—on my Father’s breast—

A half unconscious Queen—

But this time—Adequate—Erect,

With Will to choose,

Or to reject,

And I choose, just a Crown—*

This is a poem, Rich writes, “of great pride—not pridefulness, but self-confirmation…a poem of movement…of transcending.” This was a poet of power, consciousness, and courage: a poet of self-possession.

The publication history of Dickinson’s poems is also a story of possession, which the scholar Marta Werner recounts in Writing in Time: Emily Dickinson’s Master Hours, a meticulous edition of the so-called Master letters, those three unsent letters Dickinson addressed to an unknown person or persons in language that is startling, passionate, playful, and erotic:

Advertisement

and you have felt the Horizon—/hav’nt you—and did the/sea—never come so close as/to make you dance?/I dont know what you can/do for it—thank you—Master—/but if I had the Beard on/my cheek—like you—and you—had Daisy’s/petals—and you cared so for/me—what would become of you?/Could you forget me in fight,/or flight—or the foreign land?

Committed to a pristine duplication (rather than interpretation) of the physical letters, Werner has produced a beautiful eleven-by-eleven-inch square book that decidedly conveys the deep pleasure she takes in the contemplation and handling of primary documents. As she acknowledges, she “reconceives the editorial enterprise as a critical meditation and devotional exercise.” There’s no doubting that. But for some reason she does not place the facsimiles of the three letters up front—to my mind a mistake, since we need to see them before we can care about their impact or the vexed way they have come to accrue meaning since they were first published sixty-five years ago.

Preceding the facsimiles, then, Werner offers historical and textual introductions that “seek to track and explore the evolution of the documents’ material, ramifying characteristics and connections as they follow no single trajectory and run towards no certain end.” In other words, because Dickinson chose not to publish the almost two thousand poems she wrote, their publication history affects the way we read them and her correspondence. When she died in 1886 at age fifty-five, her younger sister, Lavinia, discovered a huge cache of poems, some stitched together into booklets and fastened with thread, some simply fragments of verse. Determined to see the work in print, Lavinia went for help to her sister-in-law Susan Dickinson. Emily had sent Susan more than 250 poems over the years. “With the exception of Shakespeare,” Emily once wrote her, “you have told me of more knowledge than any one living.”

But Susan dawdled, so the impatient Lavinia contacted Emily’s friend Thomas Wentworth Higginson, the author and former abolitionist. Busy and a bit nonplussed, he said he couldn’t undertake the huge task by himself, so Lavinia then turned to Mabel Loomis Todd, the wife of an astronomer at Amherst College, to transcribe the poems. Todd also happened to be the longtime mistress of Austin Dickinson, Lavinia and Emily’s brother and Susan’s husband. A family storm was brewing.

Higginson and Todd published the first edition of Dickinson poems in 1890. Together they regularized spelling, capitalization, and punctuation, and they provided titles to the poems: heretical acts if ever there were any. But the edition took off like a rocket and sold 11,000 copies within a year. The rest is history.

Well, not quite. Austin Dickinson died in 1895. Just three years later, Lavinia took Todd to court, contending that she had defrauded her of a strip of Dickinson land. Todd alleged that Austin had promised her the property as payment for editing the poems. (There was no proof.) Lavinia argued that, quite to the contrary, Todd had begged for the privilege of editing and publishing the poems in order to enhance her own reputation, not Emily’s. As it happened, Todd had set her sights on being a writer herself and had been submitting her own stories to magazines. “How I do long for a little real, tangible success,” she confided to her journal.

Though Lavinia won the suit and the land, the quarrel was never resolved. She kept the copyright to her sister’s poems but, as if in revenge, Todd locked up the Dickinson poems and papers remaining in her possession. When Lavinia died in 1899, the rights to her sister’s work went to Susan Dickinson, who died in 1913 without doing anything more about her own stash of poems. In 1914, however, Susan’s daughter published The Single Hound, a selection of poems that had been in her mother’s possession and over which she claimed copyright ownership.

A wrangle over who owned the literary rights to Dickinson’s writings subsequently degenerated into a confusion that more or less persists today. Although Todd insisted that she had permission to publish the Dickinson material in her custody, she had no written authorization, legal or otherwise. Regardless, after Todd’s death, her daughter, Millicent Bingham, published Bolts of Melody (1945), an assortment of the poems her mother had squirreled away, and then in 1955, after a legal dispute with Harvard, which had acquired the papers and poems in Susan Dickinson’s estate, Bingham was finally able to publish Emily Dickinson’s Home: The Early Years as Revealed in Family Correspondence and Reminiscences.

Emily Dickinson’s Home reproduced in full the startling Master letters, which had never before been seen: “A love so big it scares her, rushing among her small heart—pushing aside the blood and leaving her faint and white the gust’s arm.” “You ask me what my flowers said—then they were disobedient—I gave them messages. They said what the lips in the West, say, when the sun goes down, and so says the Dawn.” As Bingham judiciously observed, whether these letters were addressed to one person or several or none at all, they show that Dickinson’s “own heart was her most insistent and baffling contendent.” She quotes from one of the letters:

Advertisement

God made me—[Sir] Master—I did’nt be—myself. I dont know how it was done. He built the heart in me. Bye and bye it outgrew me—and like the little mother—with the big child—I got tired holding him.

Saluting Bingham’s “pivotal” publication, Werner points out that Emily Dickinson’s Home was eclipsed, that very same year, by the appearance of a three-volume Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by the Harvard-appointed scholar Thomas Johnson and published by Harvard’s Belknap Press; it was followed by Johnson’s three-volume edition of Dickinson’s letters. Though apparently definitive—and asserting themselves as far more reliable than any Todd/Bingham volume—Johnson’s editions suffer, Werner explains, from his obstinate assumption that Dickinson pined after an unrequited love. And of course, as she notes, all editions are inevitably stamped with the editor’s values or assumptions. (What’s more, in his introduction to the letters, Johnson announced that Dickinson “did not live in history and held no view of it, past or current”—which was absurd on its face.)

To Werner, however, Bingham represents the “unknown, unprivileged readers who follow in her wake,” precisely because those readers do not have to put up with the officious hand of an editor. Along with transcriptions, Bingham included photographs of the Master letters in her volume. Photographs or digital facsimiles of the letters deliver them directly to us, without editorial meddling, but they do not stand alone, even here. For in addition to the complicated story of their provenance, Werner offers a long explanation of how she decided (provisionally) that the three Master letters were written circa 1858–1861. And because of this, she also renames them “Master documents.” They are not merely letters, she points out, and in any case, to catalog them as such forecloses our seeing them as the experiments she believes they are.

As a consequence, Werner adds at least two poems that she thinks should be placed under what she calls “the ‘Master’ rubric”: “Mute—thy Coronation—” and “A wife—at Daybreak,” which reads in part:

A Wife—at Daybreak—

I shall be—

Sunrise—hast thou a flag for me?

At Midnight—I am yet a Maid—

How short it takes to make it Bride—

Then—Midnight—

I have passed from thee—

Unto [over] the East—and Victory

Presumably this is another poem of victory—the poet claiming herself, passing into victory and marrying, not herself or another, but poetry.

Composed around the same time as the Master letters and like the letters, these poems seem never to have been sent to anyone (as far as we know). But Werner is not interested in the identity of the so-called Master whom Dickinson may or may not be addressing, for in her writing, Werner argues, Dickinson dispenses with the need for a “stable speaker.” Rather, the Master documents, taken together, reveal a Dickinson progressively “transgressing the measure of writing and transporting writer, speaker, addressee, and reader beyond the bounds of discourse and nature.” Werner aims to show that the Master documents point to an experimental project, now lost, and yet part of the poet’s “evolving aesthetics.”

The exact nature of those aesthetics is somewhat vague, though, particularly because Werner does not quote from Dickinson’s later poetry or other letters. (Given her hesitation about editorial interventions, quoting from any published work would be understandably hard to do.) But she does include three appendices with other possible “candidates” for the Master experiment, such as the powerful “My Life had stood—a/Loaded Gun.” She also provides a fold-out timeline for the contemporaneous public events she deems significant (John Brown’s execution in Virginia, for example) and for the letters and poems Dickinson composed during those same years, such as “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers” and “A wounded Deer—leaps highest.” Werner observes:

Here it is not the exact date or even date range of a given document that is most significant but rather the larger itinerary or arc the “Master” constellation traces in Dickinson’s oeuvre and in the world to which that oeuvre was directed.

Addressing those like-minded scholars who draw from the same well of academic prose, Werner, who holds the Martin J. Svaglic Chair in Textual Studies at Loyola University in Chicago, is decidedly writing for an audience that may be as transfixed by Dickinson documents as she. She collaborated in 2013 with the visual artist Jen Bervin to design The Gorgeous Nothings, a handsome coffee-table book that reproduces facsimiles of all Dickinson’s so-called envelope writings, the poems or parts of poems that appear on envelopes, some of which Dickinson disassembled and spread into different shapes. Following its publication, there was an exhibition of many of these at the Drawing Center in New York City, which astutely posed questions about the intricate relation among concept, object, sketch, and visual format.

Such grand displays of Dickinson material are not without ideological bent. The poet Susan Howe, a provocative reader of Dickinson, had declared in her influential study The Birth-mark: Unsettling the Wilderness in American Literary History (1993) that “manuscripts should be understood as visual productions.” To her, Dickinson was spurning the material constraints of paper and print when she wrote on the back of envelopes, recipe cards, or candy wrappers. This is, in essence, an answer to the perennial question of why Dickinson didn’t publish: she refused anything conventional, from the strictures of institutionalized religion to those of polite society to the requirements imposed by a conventional book. For graphocentric scholars like Werner, then, the paper stock Dickinson chose, the type of pencil, the number of crossings out or variants on a single page, the very shape of that page, and its watermarks—all are central to any meaningful engagement with her work.

Yet the Master documents, like so much of Dickinson, remain fragmentary, secretive, gnomic. Werner frankly admits that her suppositions and inferences, whether about import or about Dickinson’s intent, are conjectural and possibly presumptuous. Regardless, she says she aims to touch “mysteries that these radiant documents both make visible and keep hidden.” Even more: in transcribing the documents, she says she “was keeping time with Dickinson.” (“The physical act of copying is a mysterious sensuous expression,” Howe once observed.) This is a romantic endeavor, to be sure, the imagined pursuit of an author, as Richard Holmes eloquently explained in Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer (1985). But the process, for Holmes, includes disenchantment and letting go. Here, the process seems to be a burrowing in.

Still, Werner broadly claims that her edition “does not proceed against the grain of previous speculation but against speculation itself.” That seems not quite true though: as Werner reasonably states, the Master documents ultimately do not belong to anyone—not to Todd or to Susan Dickinson, not to Harvard or to Amherst (where Bingham deposited her trove of Dickinson material), and not to her. It might be argued that they do not belong to their creator, Emily Dickinson, either, now that they’ve been edited, reedited, fought over, dated, disputed, deciphered, explained, and canonized.

Dickinson could have predicted as much. “In a Life that stopped guessing,” she wrote her sister-in-law, “you and I should not feel at home.” Yet what remains, in spite of all the editions and interpretations, is the fact that her poetry has touched readers for more than a century, no matter the edition in which they first discover it: whether in the best-selling, highly sanitized collection of poems back in 1890 or today in Ralph Franklin’s three-volume variorum edition. Dickinson wrote poetry of such raw emotional experience that it demands ruthless gerunds—“I felt a Cleaving in my Mind”—and her first lines alone astonish: “He put the Belt around my life—”; “The Soul has Bandaged moments—”; “Renunciation is a piercing virtue”; “The Zeros taught Us—Phosphorous—”; “Nature—sometimes sears a Sapling—”; “Remorse—is Memory—awake—”; “I had been hungry, all the Years.” She fused extremes but kept them distinct—light and dark, frailty and force, silence and noise, blazing in gold.

Parts of speech, for her and then for us, unlock the world: “Breaking in bright Orthography/On my simple sleep—/Thundering it’s Prospective—/Till I stir, and weep—.” Hers is also a poetry of mood, of change and doubt and temporary but real consolations. As she knew, sometimes “Bright Knots of Apparitions/Salute us, with their wings—.” But in the end she kept what she called a “polar privacy.” Or as she said, typically coy, “The Pedigree of Honey/Does not concern the Bee.” And still we pursue.

-

*

Fully aware of the controversies surrounding The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition, edited by R.W. Franklin (Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 1998), I am nonetheless using this edition to quote the poems that Werner does not include. It should be mentioned that Werner pays homage to the scrupulousness of Ralph Franklin, specifically for “the almost luminous clarity and textual accuracy” of his edition of The Master Letters (Amherst College Press, 1986). Whatever difficulties his Reading Edition may pose for some scholars—he could only include one version of a poem, though he identifies other versions in an appendix—again, as I’ve suggested, the problem derives partly from the unfinished state of the Dickinson manuscripts themselves. ↩