“You cannot destroy the forest without spilling blood,” observes a baobab tree near the start of Véronique Tadjo’s In the Company of Men. For centuries this baobab—“the first tree, the everlasting tree, the totem tree”—has lived in the heart of a sacred forest, protected and venerated by generations of nearby villagers. But human greed changes everything. When gold is discovered in the region there is a rush to mine it, and the trees of the sacred forest come under the ax.

Tadjo is an Ivorian writer of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and children’s books who has used both real and imagined testimonies from recent events, in works like The Shadow of Imana: Travels in the Heart of Rwanda,1 to explore the ways neighbors and loved ones define themselves through and then against one another. Born in Paris in 1955 to a French mother and an Ivorian father, Tadjo was raised in Abidjan. Among her best-known books is Queen Pokou: Concerto for a Sacrifice,2 which won the Grand Prix Littéraire d’Afrique Noire in 2005.Divided into several parts and interspersed with poetry, the book contains reworkings of the foundation myth of the Baoulé people, who make up nearly a quarter of the Ivory Coast’s present-day population. Queen Pokou, who was born in what is now Ghana in 1730 to a royal family of the Ashanti Empire, led the migration of the Baoulé to the Ivory Coast. According to legend, she was forced to sacrifice her only son in order to save her people from death at the hands of their enemies and allow them to cross the Comoé River.

Tadjo offers five different versions of the origin story. The first, “The Time of Legend,” stays close to the commonly told, “official” version: Pokou, knowing what must be done to appease the River God, throws her son into the water with little hesitation. The second, “Abraha Pokou: Fallen Queen,” underscores the danger of the journey and the suffering of the people, Pokou most of all. “Where were Africa’s forgiving Gods?” Tadjo writes. This version ends with Pokou diving in after her own child and later transforming into the vengeful Mamy Wata (a West African water spirit who is the subject of one of Tadjo’s children’s books). In the third, “The Atlantic Passage,” Pokou refuses to give up her child, and a pursuing army captures her and her followers. She is then sold into slavery. She raises her sons to be leaders, they urge their fellow slaves into rebellion, but this uprising is quashed. Her sons are “captured and hanged, their bodies dragged through the dust.” In the fourth version, “The Queen Pulled from the Waters,” Pokou falls into a deep depression at the loss of her son. The fifth, “In the Claws of Power,” casts Pokou as an avaricious schemer hardened early on by a life of palace intrigue.

By changing important elements in each version, Tadjo invites readers to reconsider the implications of the stories we grow up hearing. In all of them, however, Pokou, the people, and most of all the innocent child suffer at the hands of power-hungry politicians. The final scenes of Tadjo’s book incorporate poetry and offer a glimpse of hope. The child, resurrected as a bird, vanquishes evil in the form of a black snake that is threatening the people and soars into the sky.

Queen Pokou was published while the Ivory Coast was consumed by a civil war that began in 2002, nearly a decade after the death of longtime president Félix Houphouët-Boigny, who was a member of the Baoulé nobility. Tadjo had earlier written, more reportorially, on a civil war when in 1998 the Chadian poet Nocky Djedanoum, under the auspices of FesťAfrica, brought together ten writers from across Africa to visit Rwanda and reflect on, then respond to, the 1994 genocide. Tadjo’s contribution, The Shadow of Imana, is what the French might call a récit de voyage. It is a slim volume—just over a hundred pages—written in spare prose, in which she describes her encounters with Rwandans whose lives had been affected by the violence. The figures are mostly generic: the Journalist, the Lawyer, the Project Manager, the Writer, the Man with Masks, the Man Whose Life Was Turned Upside-Down. If a name is given at all, it is a first name only: Consolate, Anastasie, Isaro, Romain.

Tadjo interviewed, at length, the people whose stories she tells. Many were brutalized during the genocide. Others were accused of taking part. One man confessed to becoming a killer. She also attended Gacaca courts (a system of community-based courts that purported to try the foot soldiers of the genocide while promoting forgiveness and thereby reconciliation) and visited overcrowded prisons.

Advertisement

Amid apparently factual accounts, Tadjo inserts the imagined narrative of a murdered man who, angry that he is not being listened to by the living, refuses to leave this realm for the next. A diviner, brought in to commune with him, warns the people: “The dead will be reborn in every fragment of life, however small, every word, every action, however simple it may be.” Tadjo insists on revisiting Rwanda’s history. “It is important,” she said of the work she and her fellow writers produced during their residency, “for a writer to continue to prod.”3

Tadjo continues this excavation in In the Company of Men. Published in France in 2017 and recently translated into English, it is set during the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, which killed more than 11,000 people and devastated whole communities and economies. Though Tadjo does not situate the book in a specific place, the start of the epidemic has been traced to the Kissi Triangle, where the borders of those three countries meet.

The novel begins with two adventurous young brothers who catch and cook a bat that was roosting in the trees beyond their village. They soon fall ill and die, as does their mother. Their father sends away his remaining child, a daughter, instructing her to tell no one of the sickness in the village. From those first deaths, Tadjo’s novel follows the Ebola virus on its dreadful journey.

Ebola is a zoonotic disease thought to have been transmitted to humans via bats, possibly in the form of “bushmeat” but also in bats’ urine and feces, which can contaminate fruit or drop into buildings when bats roost in the rafters. With the desecration of the forests by mining companies seeking to extract gold from the soil, Tadjo writes,

bats can no longer find food, can no longer find the wild fruit they like so much. Then they migrate to the villages, where there are mango, guava, papaya, and avocado trees, with their soft, sweet fruits. The bats seek the company of Men.

Once Ebola enters the human population, the highly contagious disease spreads rapidly. “It could cross borders, travel on boats,” writes Tadjo, in the voice of the baobab tree. “It might hide in the tears of a child, in a lover’s kiss, or in a mother’s embrace.” Initially, and before specialized facilities could be built, patients were cared for at home by relatives who inevitably succumbed to the disease as well. The virus, which lives on in the bodies of the deceased, was passed to those, frequently women, tasked with preparing corpses for burial. Funerals in particular became super-spreader events.

In 2014 I was planning to fly home with my family from London to Sierra Leone, the country of my father. Our tickets had been booked for months. From the first reports in May that the virus had crossed the border from Guinea, striking the southeastern city of Kenema, I watched with growing alarm as it swiftly traveled some 120 miles northwest to Makeni, close to my family’s ancestral village of Rogbonko, where my husband and I run a primary school for two hundred children. It was simple enough to figure out what was happening: the virus was following the trade routes. From Makeni it was just another 120 miles west in a direct line to Freetown. We decided to cancel our trip.

My father was a medical doctor in the 1970s. Back then Sierra Leone’s health services were very elementary, consisting of a small number of government-run hospitals in Freetown and an inadequate network of clinics in the provinces. Most of these services were destroyed during the 1991–2002 civil war, in which an estimated 70,000 people were killed and 2.6 million (more than half the population) were displaced. Today Sierra Leone is what is called a health care desert, with most people living more than an hour from a hospital. Even if you live next door to one, the hospitals are so lacking in basic supplies that it won’t do you much good. During the Ebola crisis, most of us who knew the country realized it was completely unequipped to respond to an outbreak of any size. The World Health Organization, though, was slow to react, leaving it to NGOs like Médecins Sans Frontières to support locals. Within weeks the disease was outstripping efforts to contain it.

Though Tadjo’s fictional nation is nameless, she explains in the acknowledgments to In the Company of Men that she drew parallels with Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia. Sierra Leone’s totem tree is the cotton tree, not the baobab, but the novel’s descriptions feel utterly familiar to me: villages of extended families built in clearings in the forest; NGO workers, missionaries, and locals caught up in the same emergency but with different outcomes; poverty, desperation, a constant proximity to death. All three countries share a history of people living in small-scale chieftaincies for centuries, protected to the north from the successive empires of Mali, Ghana, and Songhai by a belt of rainforest that grew along the line of the equator. Each was then decimated by the slave trade, whose ships came by sea from the south in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Advertisement

Each chapter of the novel has a different protagonist. After the suffering boys and the account of the baobab comes a “doctor in a spacesuit,” a reference to the full-body protective gear that medics caring for Ebola patients are obliged to wear. “I feel like an astronaut floating in space, a thousand miles from earth,” he says. “The slightest tear in his spacesuit and he’s lost. The slightest tear in mine, and, just like him, I’m lost too.” With few resources at his disposal, the doctor is losing patients so quickly that he makes efforts to detach himself emotionally. Even so, he laments the death of a baby girl who dies without her mother, fed only by a syringe because the no-touch rule that applies to contagious adults applies to children, too. In the equatorial heat the suits soon become unbearable. Meanwhile, Ebola sufferers are both fighting and yielding to death, sometimes choosing eternity over another day of suffering. A patient is found with a knife under his pillow, planning to kill himself. A woman who has lost her husband and child refuses medication.

The doctor’s story is followed by the soliloquies of other characters caught up in the epidemic: a nurse, a gravedigger, a survivor, a health worker for an outreach unit, an NGO worker who had been infected during a previous epidemic in another country (possibly the Democratic Republic of Congo or Uganda, both of which saw outbreaks in the decade before), the adoptive parent of a child orphaned by Ebola, a man whose fiancée succumbs to the illness, and the Congolese researcher who first identified the virus. The dead have no voice here, as they occasionally do in Tadjo’s The Shadow of Imana. At first this seems like an omission, but perhaps she feels that the Ebola dead, in contrast to those murdered in Rwanda, are not in search of vengeance. They are the victims of a tragedy, but they were not killed by their fellow man.

Many of the testimonies in Tadjo’s new novel are delivered in the first person yet stylistically similar—the unnamed voices of everyman and everywoman. One doctor speaks for all doctors, one scientist for all scientists, and one survivor for all those who made it through alive. “We, survivors of the epidemic, suffer in silence,” Tadjo writes. “We carry invisible, painful scars. We want to lead normal lives, but the stigma of the virus keeps us apart from other people.” I would have liked to hear a greater distinctness between the voices of, say, a child raised in a rural village and a doctor or researcher, but the impact grows as voice after voice is added to the chorus, the whole becoming more than the sum of its parts.

Tadjo’s language is simple yet elegiac: “A mother is dying. Her body is giving up on her, and the end is near. Her spirit is dispersing. It collides with the walls of her house and tries to dissolve into space.” Her work has been referred to variously as prose poetry and a form of nouveau roman, both terms she rejects, insisting that she takes her inspiration from West African oral traditions. In an interview with Kwame Anthony Appiah at the Center for Fiction this past February, Tadjo talked about the influence of the griots of the northern Ivory Coast, who blend factual and political language with song and poetry.

She told Appiah she does not like linear stories. “Nothing is linear in our lives. It is a fiction,” she said. “If you want to look at a sculpture you have to look at it from all around.” She explained that the English translation of In the Company of Men, on which she collaborated (she is fluent in English), rendered the text less lyrical than the original French but added to its directness: “The characters really feel as if they are talking to you.”

The loss of the continent’s centuries-old nature-revering religions—about which the baobab has the first and the last word—brackets the book. Meanwhile, a mother who is dying after witnessing the deaths of her own children thinks that the Christian God views humanity as a failed experiment. This God loses interest in humankind: “Sometimes He goes to sleep at the back of the sun and forgets who we are. His sleep is infinite. God is bored, and His boredom is frightening.” The mother prays to the Virgin Mary, a woman who also outlived her son, and recalls this description of Mary Magdalene from the Gospel of John: “As she wept, she bent over to look into the tomb and saw two angels in white, seated where Jesus’s body had been, one at the head and the other at the foot.” It’s an echo of those people, also dressed in white, who became known as the “Ebola angels”: the medics, body collectors, and gravediggers, as well as the ambulance workers who come to take her body away in the chapter’s final scene.

The young girl who flees the Ebola-stricken village at the start of the book after the loss of her mother, her brothers, and presumably her father sees not angels or an uninterested God but a baobab tree in the courtyard of the city hospital where she is recovering. The tree’s presence gives her strength. Following her discharge from the hospital, the girl finds herself ostracized by her aunt, who fears contagion, as well as the wider community. She also suffers survivor’s guilt: she has recovered, but a doctor—the country’s only hemorrhagic-fever specialist—has died of Ebola. This is undoubtedly a reference to the Sierra Leonean doctor Sheik Umarr Khan, whose death in July 2014 was met with local and international outrage after MSF doctors at the Ebola treatment center in Kailahun decided not to give him the experimental drug ZMapp despite three days of calls between MSF, the WHO, and the health authorities of the US, Canada, and Sierra Leone.4 A short time later, the same MSF center flew its small supply of ZMapp to Liberia to treat two American missionaries who had contracted Ebola there. The missionaries ultimately survived.

Much of The Shadow of Imana reads as verbatim accounts from the people Tadjo interviewed in Rwanda. The “I” in that book is Tadjo herself; thus, when she relays first-person chronicles from survivors of the genocide, she uses quotation marks. The section in which the dead man rattles the doors and windows of the living, on the other hand, is clearly imagined. Her approach in In the Company of Men is similar but subtly altered, with a greater emphasis on the imaginary. The reader has access to the thoughts and feelings of the victims of Ebola without an intermediary. Both techniques convey the emotional weight of the grief and loss carried by survivors, but in the novel I missed Tadjo’s narrative frame. Without her guiding presence, the various sections in In the Company of Men feel less smoothly interwoven.

In 2014 Tadjo moved from South Africa to the US with a stop in Abidjan. At that time people in the Ivory Coast were already practicing what we now call social distancing, and the government was taking steps to prepare for the potential arrival of Ebola by constructing dedicated treatment centers. But in the US, as Tadjo recently told Madeleine Dobie in a conversation organized by Columbia University’s Maison Française, she was “shocked by the fact that Ebola had been given…a national identity. It was like Ebola belonged to Africa…. Suddenly Africa had become, again, the heart of darkness.”

Later in the same year, in the Sierra Leonean village of Rochain, just three miles from my family’s ancestral home of Rogbonko village, people began to fall ill and die. With no help in sight, Rogbonko decided to self-quarantine. On September 7, 2014, my cousin Morlai sent me the following texts:

EBOLA is spreading like wild fire in the harmattan. People are dying like rats. We are in trouble. Families are wiped out. Life is uncertain. Economic stagnation. Anything can happen.

People are abandoned in isolation centre to die without care. No food. Medics are dying.

Ebola has not in any way reached its peak. What the govt. is saying is quite different to what is on the ground.

Rogbonko lies at the end of a single road, in the oxbow of a river, and is almost entirely surrounded by water and forest, parts of which are sacred. This location served the residents well during the civil war—lookouts posted along the road were able to give warning of rebel approach—and during the epidemic the village was well positioned to quarantine. At the time my cousin texted me, though, harvest was only two months away. Typically, each November the rice crop is brought in by teams of young men who move from village to village clearing fields. But gatherings of more than a few people were now banned, so families collected what little of their own crops they could. The remainder rotted in the fields. With money sent by my husband and me from the charity we run to support the school and fund health care and sanitation projects in Rogbonko, Morlai organized trucks of rice and sanitation equipment—buckets, brushes, and gallons of chlorine for seven hundred people.

As Rogbonko hunkered down, other villages militarized, organizing patrols and threatening to shoot anyone who approached. Still other places, such as the Freetown slums, were under a police-enforced quarantine. Tadjo’s book gives voice to the growing skepticism and mistrust among locals as they begin to realize that the response from outside their communities—from both the government and international NGOs—will focus on containment rather than care. An NGO worker who contracted Ebola and has already been evacuated to his unnamed home country observes:

People were angry. Groups of young men armed with stones and sticks tried to rip out the barbed wire that had been put up during the night and was blocking their passage. They wanted to run away. The soldiers took aim and fired into the crowd, which started to back away. A teenaged boy cringed with pain and grasped his injured leg. A bullet had pierced his flesh and shattered the bone. Help me! In the chaos and fury that engulfed the place, no one came to his aid.

The disease that had spread so far and so fast through the compassion of carers was now making kindness dangerous. In the following chapter, an older woman is found by tracing services and asked to care for the seven-year-old son of relatives who died of Ebola. Shunned by neighbors, the boy has been living on the streets with other “Ebola orphans.” “Fear prevailed over compassion,” the woman thinks. “I’m convinced that before, he would have been immediately taken in by the neighbors until relatives came to fetch him.”

In a telephone conversation earlier in the epidemic, Morlai and I had discussed our greatest fear: that someone’s sick relative would arrive, in need of help. This was how the virus had reached the neighboring village, carried in the body of a woman who had come home from visiting relatives and was hidden and cared for by her sons. “They’ll take her or him in,” I said. “Won’t they?” And Morlai answered, simply, “Yes.” Fortunately, that eventuality did not come to pass. Though hundreds died in surrounding villages, all seven hundred residents of Rogbonko survived the epidemic.

The final episodes in the book take the form of an exchange between the virus and a bat. The virus is unrepentant because he did not ask to be disturbed from the place he had lived for centuries. Disgusted by humans and their inability to rein in their most destructive tendencies, he cares little for their fate. “Rulers, tyrants of this planet, that’s what they are, and their power is absolute,” the virus says. “Their arrogance has made them forget every limit.”

The bat tells the reader that she is sorry that Ebola escaped her belly but that it’s not her fault, either. She is a hybrid—half bird, half mammal—and she’s capable of adaptation, something humans seem to have lost in their desire for control. “Humans, alas, are still dreaming of a purity that doesn’t exist, of a unity that has never been achieved,” she says. “That’s why some of them can’t stop searching for a higher power through science.”

Tadjo concludes the novel on a note of optimism and, much as West African griots do, with a word of caution and advice for the reader. This is delivered by the baobab, who celebrates the end of Ebola and urges humankind to find a renewed respect for the natural world, because “the wheel of fortune and disaster never ceases to turn.” This ending echoes calls within the scientific community for research that places a greater emphasis on interactions between the natural world and human society.

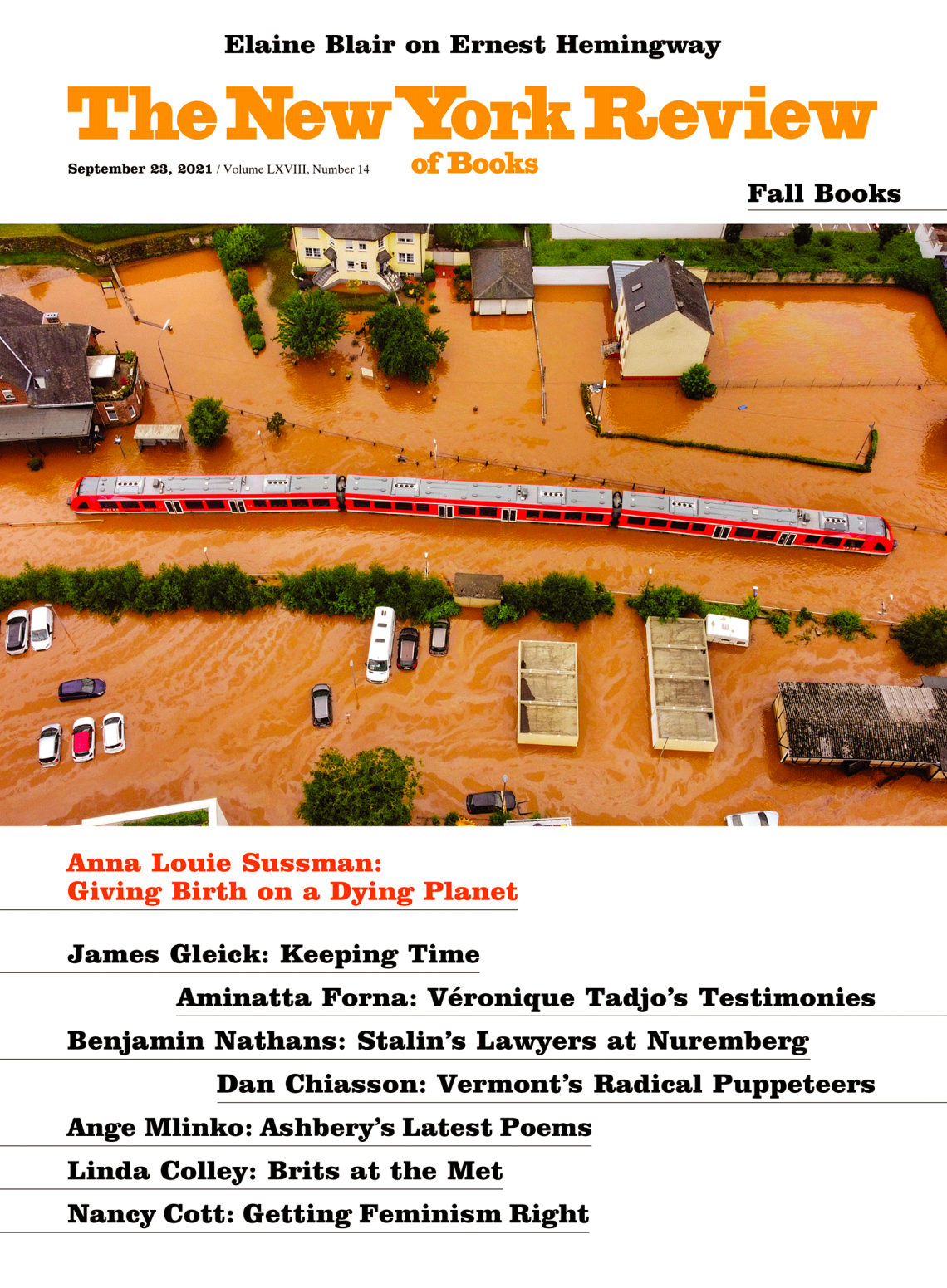

Tadjo’s chronicle of the West African Ebola outbreak illuminates the link between disease and environmental destruction. With the global spread of Covid-19, three years after Tadjo’s novel was first published, governments around the world have been forced to recognize that we are likely entering a new era of pandemics of zoonotic origin. Indeed, this year marks the start of the UN’s Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, in which indigenous knowledge of the preservation and future survival of natural environments is front and center. It is likely we will see another pandemic before that decade is through.

This Issue

September 23, 2021

Conceiving the Future

The Well-Blown Mind

Hemingway’s Consolations

-

1

Published in French in 2000 and translated into English by Véronique Wakerley (Heinemann, 2002). ↩

-

2

Translated by Amy Baram Reid and issued in 2009 by Ayebia Clarke, a small, influential UK-based publisher of African and diaspora books. ↩

-

3

See “Véronique Tadjo Speaks with Stephen Gray,” Research in African Literatures, Vol. 34, No. 3 (Fall 2003). ↩

-

4

For more on this see Paul Farmer, Fevers, Feuds, and Diamonds: Ebola and the Ravages of History (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020). ↩