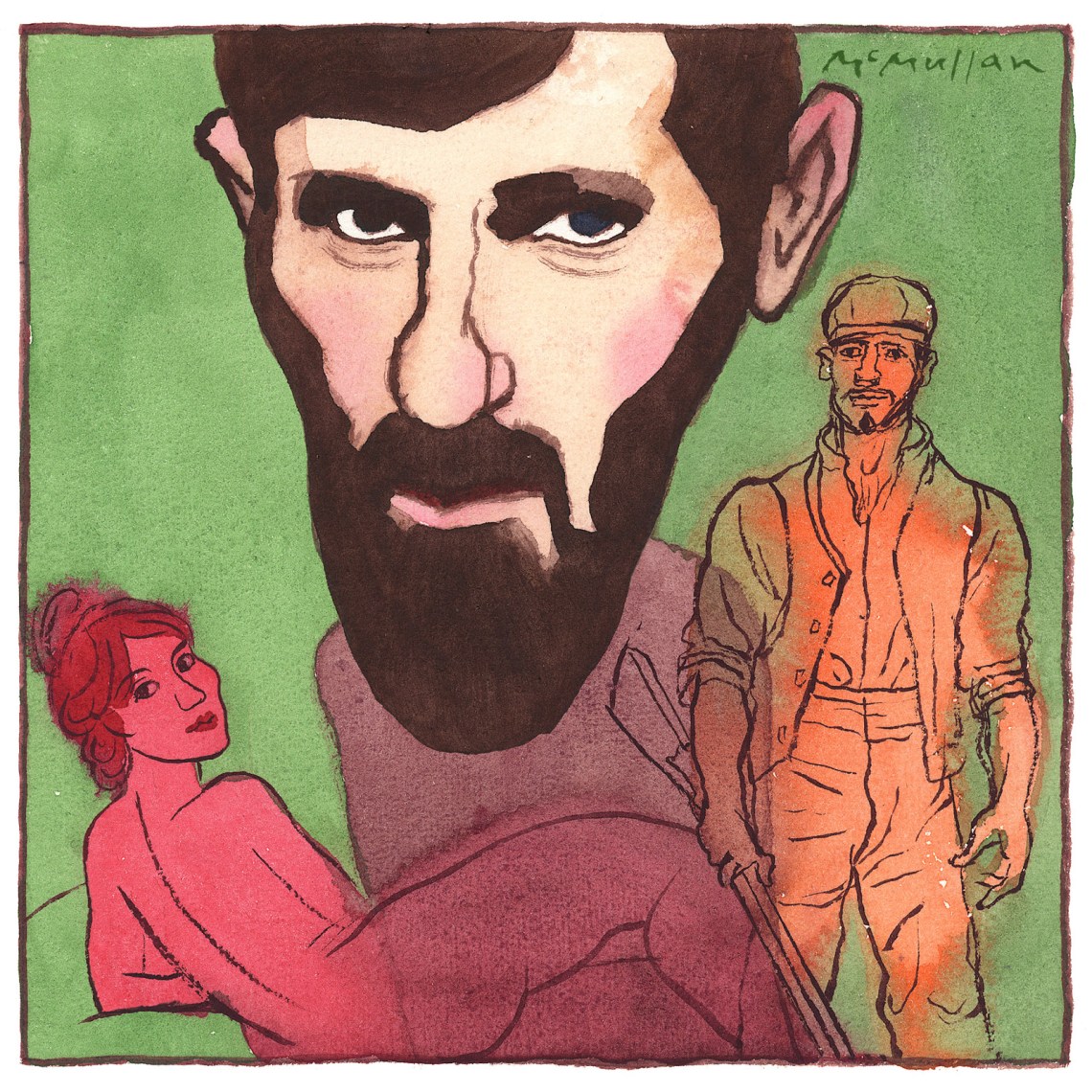

When Frances Wilson was a teenager her mother forbade D.H. Lawrence’s books in the house and her college English professor refused to teach him. It was the early 1980s and, thanks to Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics (1969), every good feminist now knew that Lawrence’s “Priest of Love” persona, based on his once-banned novels The Rainbow (1915) and Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928), concealed an ugly misogyny. Millett’s coruscating commentary had revealed how all those self-actualizing Lawrentian women—the schoolmistresses, artists, and suffragists—inevitably yield to the bullying power of the phallus in the end. Worse still, they seem to positively relish their subjection to a series of two-dimensional, noisy, and frankly fascistic men. Lawrence, so recently enshrined as a mascot of the swinging Sixties, had been unmasked by second-wave feminism as a sadistic pornographer who merely pretended to care about women.

All the same, Wilson read Lawrence on the sly, reveling in his “fierce certainties,” his indomitable belief that he was right and everyone else was not merely wrong but wrongheaded. (He lambasted his publisher, Heinemann, for rejecting an early version of Sons and Lovers (1913) as “blasted, jelly-boned swines, the slimy, the belly-wriggling invertebrates, the miserable sodding rotters, the flaming sods.”) Now, in middle age, Wilson has returned to Lawrence to find that it is his quieter “mysteries” that draw her in. This Lawrence is a modernist who aches with nostalgia, a sensualist who flinches when touched, an intellectual who devalues the intellect, and a worshiper of the body whose own waxy frame is fading away: at the time of his death in 1930, the man who had written so lushly about naked male flesh in Women in Love (1920) weighed just eighty-five pounds. In a brilliant bit of phrasemaking, Wilson calls Lawrence a “self-wrestling human document.”

Wilson has made a distinguished career out of testing literary biography’s limits and permissions. Her previous book, on Thomas De Quincey, matched structure and style to subject, so that reading it was at times like being lost in an opium haze.* She does something similar here with Lawrence, fashioning a text that feels as if it had tumbled out in the white heat of conviction. There is nothing balanced in Burning Man, nothing judicious, careful, or patient, which is exactly how Lawrence would have wanted it. Above all, Wilson resists any expectation that it is the biographer’s duty to resolve the dips, bumps, and tangles of her subject’s life. Instead, she makes a point of leaning into Lawrence’s contradictions, convinced that this is where the engine of his genius lies.

Despite The Rainbow and Women in Love being elevated to the literary canon by the Cambridge critic F.R. Leavis in the 1950s, Wilson follows Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage: Wrestling with D.H. Lawrence (1997) in maintaining that Lawrence’s novels do not represent his best work. Instead, Wilson and Dyer feel, we would do better attending to his short stories, poems, essays, reviews, sermons, and travel writing. These “minor” pieces have long been hard to find, but in 2019 Dyer brought a selection back into print in The Bad Side of Books: Selected Essays of D.H. Lawrence, which makes an indispensable companion volume to Wilson’s fine biography. In The Bad Side of Books, you will find such piercingly revealing texts as “Christs in the Tirol,” in which Lawrence sees part of himself in each of the crucifixes that he passes with his married lover, Frieda Weekley, on a walking tour from Germany into Italy:

So many Christs there seem to be: one in rebellion against his cross, to which he was nailed; one bitter with the agony of knowing he must die, his heart-beatings all futile; one who felt sentimental, one who gave in to his misery.

Matching her methodology to her man, Wilson comes at Lawrence’s work with a thrilling indifference to the old categories:

His letters are stories, his stories are poems, his poems are dramas, his dramas are memoirs, his memoirs are travel books, his travel books are novels, his novels are sermons, his sermons are manifestos for the novel.

And all of them are best understood as one continuous exercise in what today we call autofiction. “No writer before Lawrence had made so permeable the border between life and literature,” observes Wilson, “or held so fast to his native right to put everything he was into a book.”

The focus of Burning Man is the middle years, that “decade of superhuman energy and productivity” between 1915, when Lawrence, at the age of thirty, was prosecuted for obscenity after the publication of The Rainbow, and 1925, when he was diagnosed with the tuberculosis that eventually killed him. To impose shape on a life that moved erratically from Britain and Europe to Australia, Asia, and the Americas, Wilson proposes a biographical triptych based on the bold assertion that Lawrence “structured his life” according to the three parts of Dante’s Divine Comedy. By Wilson’s reckoning, Lawrence’s Inferno takes place between 1915 and 1919, when he publishes The Rainbow and comes to the realization that England will not hold him. His Purgatory occurs in Italy, from 1919 to 1922, a phase of flux and recuperation during which he extends his range through the “minor” writing that Wilson urges us to reconsider. Paradise comes in the form of New Mexico, where Lawrence is summoned by the wealthy American theosophist and patron Mabel Dodge with the promise of healthy air and the chance to save Western civilization.

Advertisement

So convinced is Wilson of Lawrence’s engagement with this medieval schema that she even maintains that each house he lived in “was positioned at a higher spot than the last,” in imitation of the upward thrust of The Divine Comedy. This is difficult to square with Lawrence’s evident love of contingency: Wilson herself tells us that he relished plotlessness, delighting in last-minute changes to social arrangements or travel plans. Like Birkin in Women in Love, he thought life should be “a series of accidents,” a picaresque novel rather than a stately piece of epic poetry.

Even with this unconvincing and cumbersome apparatus, Burning Man is an exhilarating ride. It opens during World War I with the banning of The Rainbow, Lawrence’s account of the sexual awakening of three generations of Midlands women. Sir Herbert Muskett had successfully argued for the prosecution that the book was a “mass of obscenity of thought, idea, and action,” with the result that the 1,011 remaining copies were removed from the publisher’s office and burned publicly by the hangman.

The Rainbow is actually prim compared with Lawrence’s later novels, and Wilson believes that the trial was more about the teller than the tale, to use one of Lawrence’s favorite distinctions. Not only was the young author noisily opposed to the war with Germany, but the previous year he had married Frieda, whose maiden name was von Richthofen; she was a cousin of the famous Prussian flying ace Manfred von Richthofen, known as the Red Baron. Particularly disreputable was the fact that Baroness Frieda had abandoned her British professor husband and three children to elope with Lawrence, a coal miner’s son. Disqualified from military service on account of being a poor physical specimen, Lawrence was a perfect bogeyman for these jittery times.

Relocating with Frieda to the very edge of Britain was not enough to dodge the suspicious chatter. On the Cornish coast the Lawrences were suspected of being spies: their candle at an upstairs window was said to be sending messages to German submarines; there was talk of secret supplies of gasoline hidden in the cliffs. Wilson describes the Anglo-German couple being run out of the county in 1917 “by a pitchfork-wielding mob,” which is what it must have felt like when they were, in fact, given official notice to leave by four officials who burst into their cottage with a formal expulsion order.

Returning to London, Lawrence became close to Hilda Doolittle, the first of the three companions whom Wilson has picked to accompany him on his Dantean quest. An American imagist poet and protégée of Ezra Pound, Doolittle had married the British writer Richard Aldington and was now living in Bloomsbury. In Wilson’s telling it is H.D., as she preferred to be known, who gives Lawrence a perch in a literary establishment that had never warmed to him. The dominant Bloomsbury group found Lawrence exotically, which is to say contemptibly, working class. To Virginia Woolf he became a “cheap little bounder,” while for the novelist David Garnett he was reminiscent of “the type of plumber’s mate who goes back to fetch the tools.” Meanwhile, Ford Maddox Ford, editor of The English Review, which published Lawrence’s first poems in 1909, had been anxious about meeting this working-class lad, in case the boy should call him “Sir.” Ford need not have worried: the jaunty young poet strolled into the Review’s office like “a fox going to make a raid on the hen-roost.”

As a native Pennsylvanian H.D. was less concerned with Lawrence’s provincial vowels and “plebeian” hair than she was with constructing a fantasy in which together they would undertake great, if unspecified, work. According to Bid Me to Live, the roman à clef she published at the end of her life, Lawrence had told her early on that “Frieda was there forever on his right hand, I was there for ever—on his left.” Yet no matter how deliberately H.D. contrived the sleeping arrangements at her Bloomsbury flat, where the Lawrences had taken temporary refuge, this “perfect triangle” never cohered. Not least because Frieda, sensing her hostess’s predatory geometry, confided to H.D. that her husband was homosexual. From here it was only a matter of time before Lawrence was writing to H.D., “I hope never to see you again,” which is how his friendships always ended.

Advertisement

In truth, the role that H.D. plays in Burning Man is less cicerone than counterweight to the unshiftable Frieda Lawrence. Wilson is careful not to join Lawrence’s friends in scapegoating the brash, blousy woman who truly believed that her husband (younger by six years) could not write a word without her. So there Frieda sits, legs apart, with a cigarette hanging out of the corner of her crooked mouth, sharing her “happy flesh” with anyone who takes her fancy. (Wilson makes a great deal of her sexual confidence.) She sees Frieda as a figure from an Otto Dix painting, but Punch and Judy also comes to mind. When in company Frieda and Lawrence would fly at each other with their fists, requiring an ever-changing audience to keep the drama of their marriage going. He instructed her to dress like his late sainted mother, she told everyone that she played a big part in the writing of his novels, he yelled that she was a ghastly Prussian. Only in private, when no one was looking, would they consent to be tender.

“One must retire out of the herd and then fire bombs into it,” declared Lawrence in 1916. As his guide for this part of the journey Wilson appoints Maurice Magnus, a minor man of letters whom Lawrence first met in Florence through the writer Norman Douglas. She devotes many pages to this American mongrel who had grown up in Europe learning “to speak several languages badly, to produce indifferent prose, to mismanage money, to appreciate good food and keep up appearances.” These “appearances” rested precariously on Magnus’s cherished belief that his late mother was the illegitimate daughter of Kaiser Wilhelm I, a connection he felt entitled him to live like a prince at other people’s expense.

Wilson rifles Lawrence’s own glorious phrasemaking to give us a vivid sense of “the impossible little pigeon.” Before long, Magnus is sponging off Lawrence. At first it is just a drink or dinner, but soon he is expecting Lawrence to settle his hotel bills (he always picks the fanciest). Normally this would be the cue for some spluttering invective from Lawrence, who remained frugal all his life, as befits a boy who had grown up in a row house with an outside communal toilet. Yet he retained a curious soft spot for this preposterous companion, even arranging to stay at the Benedictine monastery on Monte Cassino where Magnus hoped to one day enter the order.

In 1920, about to be arrested for debt in Malta, Magnus swallowed prussic acid. Lawrence insisted that he felt no guilt about the fact that “I could, by giving half my money, have saved his life” but chose not to. By way of reparation, he set about finding a publisher for the memoir that his “friend”—Magnus’s code for a homosexual lover—had left behind, with all the profits going to pay off outstanding debts. This manuscript went by the delightful title Dregs and dwelled with lavish obscenity on the author’s time in the French Foreign Legion. To have any hope of publication, though, the sado-masochistic sex would have to go, and the title changed to the altogether less enticing Memoirs of the Foreign Legion by M.M., with an introduction by D.H. Lawrence.

Lawrence believed that his eighty-six-page introduction to the memoir was the “best single piece of writing, as writing” that he had ever done, an assessment with which Wilson emphatically agrees. It is also, however, a cruel, cruel thing. Lawrence skewers his friend as an effeminate stooge, twirling around in a blue silk kimono that made him resemble a “little pontiff,” his rear end permanently stuck out like a small bird’s. It was as if, having once got too close to Magnus for comfort, Lawrence now felt the need to kick him away and then stomp on his head. After its publication in 1924 Lawrence sent a copy of the memoir, complete with his character assassination, to the monks on Monte Cassino. It was the one place he knew that Magnus really cared what people thought of him.

It sounds small, petty, and mean, the sort of thing writers might do when their real work has stalled and they feel a need to punish someone. Yet Lawrence’s creative life was richer than it had been in years. It was during this time that he produced much of the verse that appeared eventually in Birds, Beasts and Flowers (1923), including the incomparable “Snake,” which describes a hot noon encounter at a water trough with a venomous reptile, transformed by the poet’s venerating gaze into “a king in exile.” This was also when Lawrence produced “the finest opening line of any travel book,” according to Wilson, whose declarative certainty begins to match Lawrence’s. To be sure, the first line of Sea and Sardinia (1921) is sublime: “Comes over one an absolute necessity to move,” and from here Lawrence embarks on a propulsive narrative in which he and Frieda are cast as comic travelers who spend nine days touring the Mediterranean island. She is the Queen Bee, or q-b; he is the hapless factotum, in charge of the all-important “kitchenino” out of which, always the homey one, he magics picnics of tea, sandwiches, apples, butter, sugar, and salt.

Sea and Sardinia blurs the boundary between interior and exterior movement, a kind of travel writing that had not quite been seen before. Approaching the island by ferry, Lawrence describes how “suddenly” there is Cagliari, “a naked town rising steep, steep, golden-looking, piled naked to the sky…like a town in a monkish illuminated missal.” Perhaps it is the reference to monks and hilltop communities or even all that nakedness, but soon Lawrence’s thoughts skitter back to his favorite plaint, the corruption of masculinity in modern times. Once onshore he is disturbed by the way that the local Sardinian men are dressed as women (it is fiesta time), vexed too about the way that he himself buzzes around the q-b like an abject courtier: “One realises, with horror, that the race of men is almost extinct in Europe.”

It turned out to be under siege in America, too. The Lawrences traveled to New Mexico in 1922 at the behest of Mabel Dodge, who several years earlier had arrived from the East Coast on a divinely appointed mission to “save the Indians.” Once this had been accomplished, she planned to move on to the whole of white America, which she would teach to give up capitalism and revert to the mysticism and communal life of the pueblo.

As a first step in this ambitious project, Dodge had taken as her fourth husband Tony Lujan, a Taos Pueblo man. Now she summoned Lawrence from the other side of the world using what she claimed was one of her two wombs. This invitation also involved the more workaday method of writing him a letter. Dodge had become obsessed with Lawrence after reading his Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious (1921), and her idea was that he would interview her and “take my experience, my material, my Taos” and “formulate it into a magnificent creation.” Unfortunately for Dodge, the books that Lawrence proceeded to write out of their encounter were some of the maddest and meanest of his entire career.

“The Woman Who Rode Away” (1925) is the piece of work that most disturbed Kate Millett in Sexual Politics. In this dreamlike fable a wealthy white woman—a barely disguised Dodge—travels to Mexico to discover the secrets of the Chilchui people. The Indians explain to her that she, or rather what she represents, has “stayed too long on the earth” and her death will be an offering to the gods and a means of saving the tribe. The story ends with her naked on a sacrificial slab, waiting for the tribal elder to plunge his knife deep into her entrails. The story, thundered Millett, was not only “monstrous,” “demented,” “sadistic pornography,” but Lawrence’s “most impassioned statement of the doctrine of male supremacy and the penis as deity.” It was also a vicious personal attack on Dodge—“too damn mean,” she confided to Leo Stein later.

Wilson offers no defense, conceding at once that Lawrence was by this point “a semi-sane bore.” What she does ask us, though, is to consider that only recently Lawrence had published Studies in Classic American Literature (1923), which she describes as “the greatest work of literary criticism of the age.” In the first of these essays, “The Spirit of Place,” Lawrence argued that America was not the innocent fresh-faced child of Europe, but its untranslatable “other.” (He was the first to use the word “other” in the sense of radical alterity, Wilson observes.) There is, he suggests, an undercurrent in American literature that is bent on destruction, on smashing through its suave self-presentation. Wilson urges us, then, to read “The Woman Who Rode Away” symbolically, as an allegory in which capitalist America must die in order to ensure that the life of the tribe continues.

The story was wildly unpersuasive and, in any case, within months Lawrence was no longer convinced that the Pueblo Indians were the people who could save modern America. Disappointed with them, as he always became with those he had once idealized, he decided that they were “without any substance of reality…. No deeper consciousness at all.” Dodge, not unnaturally, was tired of being told she was lazy and should wear an old-fashioned apron like Lawrence’s mother and scrub her own floor. How pleasing to note that, this time, it was she who wrote to end their connection, telling Lawrence that he “was incapable of friendship or loyalty—and that his core was treacherous.” She went public too, publishing Lorenzo in Taos two years after Lawrence’s death; in the book, shades of Bloomsbury, she made a point of mentioning that his nose was particularly vulgar.

Frances Wilson ends her narrative in 1925, glossing over the final five years of Lawrence’s life, which include the writing of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. She maintains that Lawrence is still “on trial,” but there are signs that the jury may be tipping in his favor. Earlier this year Rachel Cusk published Second Place, a novel that reworked Lorenzo in Taos and made the Booker longlist. Alison MacLeod, meanwhile, has just published Tenderness, a novel that fictionalizes a brief affair that Lawrence had with Rosalind Baynes in 1920. The cultural historian Lara Feigel is working on a critical reassessment of Lawrence.

He remains one of the most frequently biographized subjects in literary history. “He’s had more books written about him than any writer since Byron!” exclaimed his friend Aldous Huxley in 1960, and there have been plenty more since then. But what interests these writers and scholars are acts of revision and recuperation. For all Lawrence’s hateful misogyny, racism, and plain bad temper, they believe that there remains something in his work that is urgent and alive. He never states an opinion without almost immediately countering it, such that to read him is to catch him in the very act of creation. Most importantly, perhaps, Lawrence grants readers permission to give up fretting about elegance, concision, likability, and all those other qualities we know we shouldn’t set such store by but do.

This Issue

November 18, 2021

Bringing the Supply Chain Back Home

Trains to Nowhere

-

*

Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas De Quincey (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016); reviewed in these pages by Richard Holmes, November 24, 2016. ↩