Who were America’s worst presidents? In a 2021 survey of historians, C–SPAN found that Andrew Johnson ranked next to last, just above James Buchanan and below Franklin Pierce, who was tied with Donald Trump. A 2021 ranking of “the 10 worst US presidents” by US News and World Report put Johnson third from the bottom, ahead of Trump and the perennial loser, Buchanan.

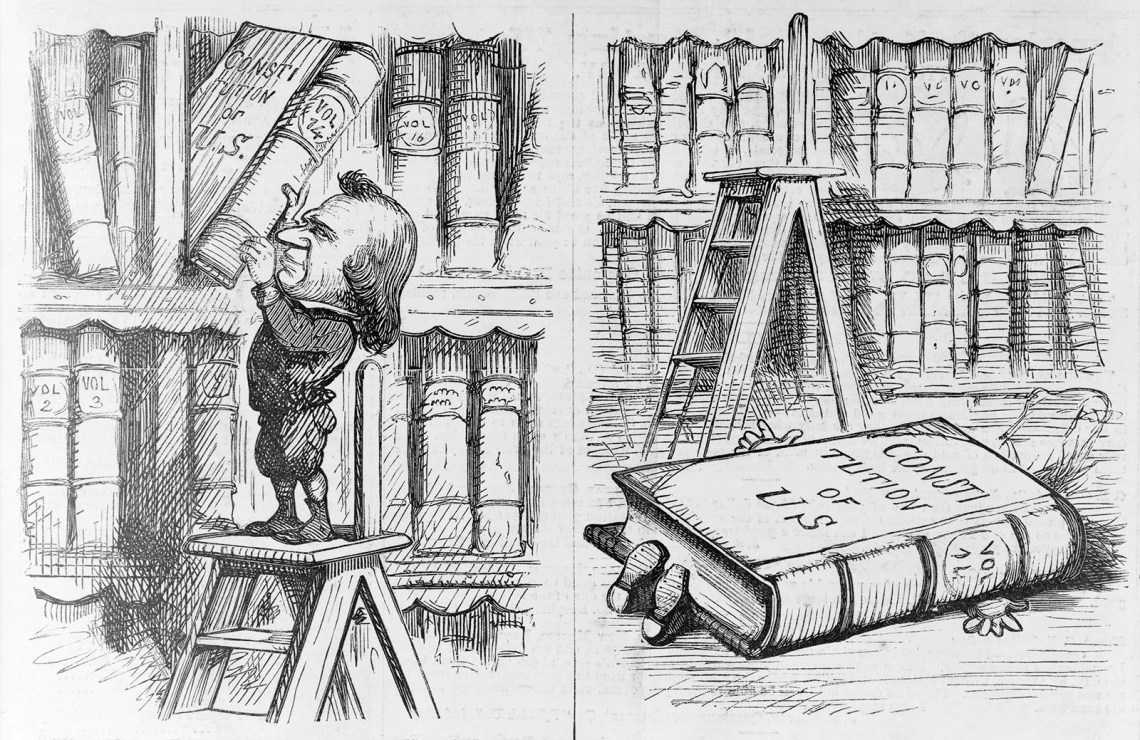

Johnson wasn’t always viewed this negatively. The so-called revisionist historians and biographers of the Jim Crow era saw him as a man of conviction who, despite some flaws, adhered to the Constitution in a time of crisis and boldly defied the Radical Republicans in Congress who led the effort to impeach him.1 From this perspective, Johnson’s Republican opponents were fanatics who after the Civil War were overly intent on punishing former Confederates and pursuing rights for Black people. Johnson, so the story went, was a champion of constitutional order, while his foes were deluded power seekers. The pro-Johnson view was so influential that John F. Kennedy, in his book Profiles in Courage (1956), sang the praises of Edmund G. Ross, the Kansas senator who at Johnson’s impeachment trial cast the decisive vote against his removal from office.

The civil rights movement in the 1960s precipitated Johnson’s fall from grace. He is now widely seen as an intransigent racist who vetoed civil rights legislation and did what he could to block the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, which among other things guaranteed birthright citizenship and the equal protection of the laws.

Could Johnson’s reputation be restored? In the opening section of The Failed Promise, Robert S. Levine takes on the formidable challenge of rehabilitating Johnson’s early career, arguing that at the start of his presidency he actually seemed to have great potential. Levine describes Johnson as a self-made man in the pattern of Andrew Jackson or Abraham Lincoln. Born into poverty in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1808, he moved at seventeen to Tennessee. An autodidact, he had no formal schooling yet learned to love reading. He worked his way up through humble jobs to become a forceful orator and a prominent Democratic politician who won favor among Tennessee voters by presenting himself as the champion of the common man, serving as a congressman, as governor, and, beginning in 1857, as a US senator.

During the Civil War, Johnson was the only senator from a Southern state to remain loyal to the Union. He denounced the Southerners who formed the Confederate States of America. A slaveholder, he liberated his bondspeople in 1863 and made a fervent appeal for immediate emancipation. In recognition of his loyalty to the Union, Lincoln appointed him the military governor of Tennessee and approved of him as his running mate in 1864. Levine emphasizes positive aspects of his early development:

Johnson was a wide reader with a special interest in the writings of the nation’s Founders…. He always supported his political positions through sustained and informed analysis…. When he made the bold decision as a southerner to reject southern secession, he offered precedents to explain himself. When he championed antislavery as a southerner—at the risk of his life—he developed his critique using contemporary and historical examples in the fashion of a northern abolitionist.

A highlight of Johnson’s Civil War experience, Levine tells us, was a speech he gave in October 1864 in Nashville before a largely Black audience, in which he presented himself as an enlightened champion of the enslaved. Allegedly outraged that Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had not set free bondspeople in the border states, he announced, “I, Andrew Johnson, do hereby proclaim freedom, full, broad and unconditional, to every man in Tennessee!” He called for some Black person to rise up and be a Moses to the enslaved, leading them to freedom and happiness. When members of his audience shouted, “You are our Moses…. We want no Moses but you,” he replied, “Well, then…humble and unworthy as I am, if no other better shall be found, I will indeed be your Moses, and lead you through the Red Sea of war and bondage, to a fairer future of liberty and peace.” Johnson repeated the Moses metaphor time and again, right through his presidency.

Johnson’s gestures of sympathy to Black people, Levine shows, initially won over a number of antislavery radicals. William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator ran an article called “Andrew Johnson’s Great Speech to the Colored People.” Garrison’s fellow activist Wendell Phillips called him the “natural leader” of the abolitionists. The Republican senator Charles Sumner wrote a friend, “I am satisfied that he is the sincere friend of the negro, & ready to act for him decisively.”

Advertisement

After becoming the “Accidental President” upon Lincoln’s assassination, Johnson seemed promising to those who wanted to follow up the North’s victory in the Civil War by taking stiff measures against former Confederates. Having declared during the war that secessionists should be “tried for treason” and, if convicted, “suffer the penalty of law at the hands of the executioner,” he gave signals early in his presidency that he would treat the South with righteous sternness. Johnson’s apparent resolve, however, proved illusory. Within weeks of assuming office, he extended pardons to most ex-Confederates. He justified his embrace of the Southern states by insisting that they had never actually left the Union, because the Constitution did not allow secession.

Antislavery Republicans now fought him tooth and nail. They insisted on excluding former secessionists from Congress until the South was reconstructed, by dividing it into Northern-controlled military districts where the rights of African Americans could be protected. Johnson, in contrast, called for the immediate admission of ex-Confederates to Congress and the restoration of the Union rather than the reconstruction of the South.

It was now clear that Johnson’s seeming progressiveness was a thin cover for his actual indifference about people of color. He opposed every piece of progressive legislation Congress approved. He vetoed the Freedmen’s Bureau Act, which provided schools, food, clothing, and land for previously enslaved people. He also vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which awarded citizenship to anyone born in the United States “without distinction of race or color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.” (Native Americans were excepted.) Johnson declared that the civil rights bill was “fraught with evil” because it gave too much power to the federal government. He argued that states should decide on racial matters, even if they passed laws that enforced discrimination. Congress responded by overriding his vetoes and passing a series of acts that resulted in real advances for Southern Blacks during the early years of Reconstruction.

When Johnson fired his war secretary, Edwin Stanton, who was increasingly resistant to the president’s hidebound attitudes, the Republican-led House started impeachment proceedings on the grounds that he had callously ignored the decisions of Congress and had violated the Tenure of Office Act, which called for Senate approval of political firings. After a two-month trial in the Senate, Johnson was acquitted by one vote.

A remarkable section of The Failed Promise is an account of a meeting between Johnson and Frederick Douglass and other Black leaders who visited the White House in January 1866. In the meeting, which was scrupulously recorded by a stenographer, Johnson barely listened to the pleas of Douglass and the others for recognition of Blacks’ civil rights. He cluelessly asked Douglass if he had ever lived on a plantation, evidently unaware of his memorable description of enslavement in his 1845 autobiography. In similarly ham-handed fashion, Johnson commented that enslaved people actually respected slaveholders more than they did working-class whites, and boasted that although he had once owned slaves, he had never sold any of them. When Douglass raised the issue of giving Black people the vote, Johnson said that doing so would cause a war between the races that would lead to the extermination of African Americans. Perhaps the best option for Blacks, he suggested, would be for them to leave the country.

The discomfort of his guests was palpable. Levine quotes a reliable source who reported that Johnson said after the meeting, “Those d—d sons of b—s thought they had me in a trap! I know that d—d Douglass; he’s just like any nigger, & he would sooner cut a white man’s throat than not.”

Such racism, Levine reminds us, was pervasive in that era and even tinged the attitudes of Johnson’s Radical Republican critics. Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio vigorously promoted Black rights in the South but not in the North, evidently because of racial prejudice among their constituents. Despite Stevens’s reputation as a racial egalitarian, he resisted inviting Douglass to a political convention because, in his words, “the old prejudice, now revived will lose us some votes.” Wade, during a trip to the South in 1854, had complained about “the Nigger smell” and said he hated eating food “cooked by Niggers until I can smell and taste the Nigger.” Even after fighting against Johnson’s policies in 1866, Wade wrote his wife, “I am sick and tired of niggers.”

In the process of delineating the complexity of both Johnson and his opponents, Levine shortchanges Lincoln. The early chapters of The Failed Promise give the impression that during the Civil War Johnson was at least as forward-looking on racial matters as Lincoln, sometimes more so. For instance, Levine writes that the “extraordinary,” “startling,” “stunning” Moses speech saw Johnson “positioning himself as a radical in relation to the moderate Lincoln.” Levine mentions Lincoln’s occasional displays of conservatism without explaining that as president, he at times had to lean publicly to the right in order to keep the border states in the Union and to counter opponents’ charges that his policies would bring about a nightmarish racial upheaval in America.2 By the same token, Levine portrays Douglass as predominantly anti-Lincoln during the war years. Actually, he moved from early wariness to the view that Lincoln was “emphatically the black man’s president,” one whose “entire freedom” from racial bias struck Douglass on his visits to the White House.

Advertisement

Levine notes Douglass’s perception that Lincoln evolved, to the point of approaching civil rights activism toward the end of his presidency. Another interpretation might be that events peeled away the moderate veneer that had made Lincoln appear an effective unifier to those seeking stability in a deeply divided nation. After Lee’s surrender to Grant, he shed almost all of his outward restraint, so that his inwardly radical self stood forth. In his last public speech, delivered impromptu from a White House window, he became the first president to call openly for limited suffrage for Blacks.

Events also stripped away Johnson’s veneer, but they revealed an unsightly bigot. He declared, “Everyone would and must admit that the white race is superior to the black.” Sounding much like Senator Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln’s Democratic nemesis in the 1850s, Johnson was heard to say, “This is a country for white men and, by G—d, as long as I am president it shall be a government for white men.”

While the significant contribution of Levine’s The Failed Promise is its illumination of Johnson’s perspective on African Americans, Brenda Wineapple’s The Impeachers stands out for its thoroughness in describing the social and political background behind his impeachment. Wineapple describes Johnson-like attitudes playing out across the US. Especially moving is her account of race riots in Memphis in May 1866 and in New Orleans two months later.

The Memphis affair began when a group of African Americans who were toasting Lincoln and celebrating their discharge from the army were spotted by whites, one of whom yelled, “Your old father, Abe Lincoln, is dead and damned.” A fight broke out that led to an all-out assault on Blacks by whites, including a judge on horseback who urged his fellows “to go ahead and kill the last damned one of the nigger race…. They are very free indeed, but, God damn them, we will kill and drive the last one out of the city.” Cheers went up for “Andy Johnson” and a “white man’s government.” By the time the violence ended, forty-six Blacks were dead, at least five Black women had been raped, and scores of Black homes, churches, and schools had been torched. The New Orleans riot flared in a similar way. A political meeting of Blacks in the Mechanics Institute was interrupted by insult-spouting whites who went on a rampage that left more than one hundred dead and at least three hundred wounded.

Johnson’s response revealed his moral bankruptcy. A month after the violence in New Orleans, during the nineteen-day speaking tour known as the Swing Around the Circle, he blamed the riots on his political opponents, who, he said, promoted the empowerment of Blacks and resisted his pro-Southern policies. On the tour, he was confronted by hecklers who jeered, “Three cheers for Congress” and “Why don’t you hang Jeff Davis?” He shouted back, “Why don’t you hang Thad Stevens and Wendell Phillips?” His speeches were called by one journalist “the ravings of a besotted and debauched demagogue” and prompted another to ask, “Was there ever such a madman in so high a place as Johnson?”

Several times in her book, Wineapple zooms out and gives a picture of the politicians, reformers, and authors on the postwar scene. She demonstrates that there was a widespread softening of radicalism in the interest of reconciliation and leaving the Civil War behind. The Thirteenth Amendment’s abolition of slavery was sufficient for Garrison, who thought that Black citizenship could wait, and for the antislavery clergyman Henry Ward Beecher, who declared that Blacks should be left to seek social and political advancement on their own. Herman Melville sounded much like Johnson when he said that former slaves needed “paternal guardianship” and that the activism of Radical Republicans might arouse the “exterminating hatred of race toward race.” Walt Whitman, who called for compromise, saw both Johnson and his opponents as dangerously divisive.

Wineapple also brings attention to a number of those close to Johnson who retreated on civil rights. Two holdovers from the Lincoln administration, Salmon Chase and William Henry Seward, are especially surprising. Earlier in his career, as an Ohio lawyer, Chase had been known as the “attorney general of fugitive slaves” because of his fearless courtroom defenses of Blacks. He served as secretary of the treasury under Lincoln, who in 1864 appointed him chief justice of the Supreme Court. The formerly firm-principled Chase changed after Johnson took office. He “drifted away from his earlier radicalism,” Wineapple writes, supporting voting privileges for former prominent Confederates and opposing the military occupation of the South.

Even more remarkable in this regard is Seward, Lincoln’s and Johnson’s secretary of state. Before the Civil War, he had established himself as one of the nation’s most outspoken antislavery politicians. His declaration that there was a higher law than the Constitution—the moral law that demanded justice for enslaved people—inspired abolitionists while infuriating conservatives. The same was true of his controversial announcement of an “irrepressible conflict” over slavery. In light of this record, it is astonishing to read Wineapple’s account of him as a lackey of the reactionary Johnson. Seward, she tells us, was an “unapologetic Johnson booster” who called the president “a true firm honest affectionate man—perhaps the truest man he has almost ever known.”

Wineapple provides an especially full explanation of the impeachment, trial, and acquittal of Johnson. Eleven articles of impeachment were submitted to the Senate, eight of them related to his firing of Stanton and one to his

intemperate, inflammatory, and scandalous harangues…against Congress [and] the laws of the United States duly enacted thereby, amid the cries, jeers and laughter of the multitudes then assembled and within hearing.

Johnson’s trial in the Senate, presided over by Chief Justice Chase, began on March 5, 1868, a year before his presidential term was to end. Wineapple does an excellent job of probing the judicial and political maneuverings behind the trial. What amounted to a dream team of attorneys defended Johnson. They argued that the Tenure of Office Act did not apply to the firing of Stanton, who had been appointed by Lincoln, not Johnson. As for Johnson’s hostile responses to Congress, they were protected as free speech under the Constitution.

It wasn’t just lawyerly shrewdness that prevented Johnson’s conviction; it was also wishy-washiness on the part of some of his opponents in the Senate. Several Republicans who had spoken out against him ended up voting for his acquittal. Wineapple indicates that corruption shadowed the trial. “There must have been payoffs, bribes, and bullying,” she writes. In particular, Edmund G. Ross, the senator whose vote saved Johnson, appears to have been bribed or promised favors. Nonetheless, Wineapple notes, the trial “proceeded in an orderly, even elegant fashion.” At first the Senate gallery was packed with spectators, but the crowd dwindled as mind-numbing legal arguments were laid out over seven weeks, with the acquittal coming in late May.

Although Johnson remained in office, he became a shadow president. His exoneration led Thaddeus Stevens to grumble, “The country is going to the devil.” Stevens had reason for pessimism. The white supremacy exhibited by Johnson and others of his era persisted; it reached a nadir during Jim Crow and, of course, remains a fraught political issue today.

However, Johnson’s opponents gained major victories. Justifiably, the Radical Republicans are the heroes of Levine’s and Wineapple’s books. Although the Radicals did not shed completely the racial attitudes of their time, they never lost sight of their goal of reconstructing the Southern states on the basis of rights for African Americans. The landmark laws and constitutional amendments they passed laid the groundwork for civil rights and opened up political participation for people of color. Despite the racist legacy of Andrew Johnson and his supporters, the Radical Republicans managed to forge an egalitarian ideal to which later generations could aspire.

-

1

For succinct summaries of historians’ shifting views of Johnson, see Edgar Toppin’s review of Eric L. McKitrick’s Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction in The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 45, No. 4 (October 1960); and Carmen Anthony Notaro, “History of the Biographic Treatment of Andrew Johnson in the Twentieth Century,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Summer 1965). ↩

-

2

See my Abe: Abraham Lincoln in His Times (Penguin Press, 2020), chapters 15 and 20. ↩