Sometime toward the end of the twentieth century I dimly recall in the culture and among the people I knew a generationally ambient feeling that marriage was no longer an important theme or plot point in storytelling—and this included the story of one’s own life. Marriage was a trap into which one should not be irrationally enticed, and from which one would want ultimately to escape, a diminished sideshow and distraction from life’s main projects of personal autonomy, meaningful work, self-actualization, political activism, and noble causes generally.

Or so went the conversation. Tinged with patriarchic taint, marriage was not the mutual journey and social necessity it had been promoted as, and for women in particular this became a feminist idea. A bride who took her husband’s surname was not forming a team or partnership but taking the “slave name,” and in so doing was acknowledging the vexed nature of the institution while still participating in it. The erosion of one’s own personality was inevitable and could lead only to bitterness. The stigma of divorce seemingly gone and its traumas under-advertised, whether marriage happened or not, succeeded or not, was not a priority for my immediate peer group. Weddings were infrequent, and if you cried while attending one, the tears were a surprise, and their meaning was unclear.

But marriage remains one of the biggest structural and emotional decisions one makes in life. It determines so much of one’s future (and precipitates a conversation with one’s past), no matter how casually one enters into it. I remind my students of this—especially when we are discussing whether the literary concerns of Jane Austen, Henry James, and Edith Wharton are outmoded—and the students from South Asian and African countries have sometimes appeared to understand this best, with respect and trepidation. Marriage has much to do with community and family, things that in this country keep collapsing and then getting rebuilt in new and often inventive ways. Being in an American marriage can feel simultaneously dangerous to the self and societally protective of the individual, in the ways that activists for gay marriage have enumerated over the years (taxes, health care, housing).

The business of couples therapy, taken up by shamans, clergy, MSWs, psychologists, and psychiatrists with both medical and analytic training, shines a spotlight on the difficulties of marital arrangements when the two people begin to awaken from initial romance, flex, and stretch apart: someone has changed who wasn’t supposed to; someone hasn’t changed who was expected to. The desire for personal growth plus affectionate companionship, sexual appreciation, and spiritual renewal are all placed within a fragile marital arrangement originally designed for the management of property and offspring. Of course, money and children are often the main issues in marital discord and are thus prominent topics in couples therapy. As is communication: one person has usually persuaded their more reluctant partner to embark on this verbal project. A third party is needed to referee and interpret. More speech, however exhausting, is required, if not necessarily desired, by everyone. Human language was invented only 70,000 years ago—it sometimes just feels longer than that.

That these therapeutic sessions are also often theatrical—that is, the marriage is performed for an audience, its problems enacted for a critic in that audience—has not gone unnoticed by the theatrical world. (Most recently, Jeremy O. Harris’s Slave Play used psychodramatic couples therapy as its structure.) And now television, in a strange but elegantly edited reality show on Showtime, a “docu-series” titled Couples Therapy, has also gotten into the business of turning our intimate lives, with their negotiations and compromises, into theater. The series offers up some real-life New York City couples who have agreed to do their therapy in front of a camera. Perhaps some of them are would-be actors: many are charismatic and unafraid, as if auditioning for agents. All are articulate and a little sad. Occasionally there is reassuring laughter, which is the sound of hope. There is no story arc, but there is growing comfort and optimism as the series proceeds to the finale of each season.

That couples seek therapy during the death throes of a collapsing relationship is something of a truism—and one not contradicted in the series, though there is also footage of the couples out and about in the city, usually looking happier than they do in the office of Orna Guralnik, the empathic and beautifully accessorized therapist. (A viewer would not be faulted for coveting her necklaces. Or her well-trained dog, a blue-eyed miniature husky.) Guralnik, through two seasons and nineteen episodes, does her best to ferret out the underlying truths of these intertwined individuals while also disrupting their unhelpful self-presentations. Mostly what the spouses are looking for is to be seen and to be heard. “Say your version, unedited” is a typical directive from Guralnik. Or, “Anger is rarely a primary emotion. Usually anger is some kind of defense against something else. People usually don’t like to feel vulnerable so they put up anger.”

Advertisement

The show’s exterior photography is often a valentine to New York City. Glimpses of two people snuggling on a bench or holding hands or sharing earbuds are part of the camera’s romantic urban panorama. Couples stroll in parks, take the subway, sit at a café, sometimes checking their phones (no valentine is perfect). Indoors it is often a different story. In Guralnik’s tiny waiting room there is some framed Abstract Expressionist art, what looks like either a Franz Kline or Willem de Kooning print. In either case, it is a Rorschach test: waiting tensely for the doctor to invite them in, the couples sometimes guess what the painting might represent—an ax, a bird, a broken sign.

Well, a bird is already a broken sign. Eventually, Guralnik switches out the waiting room print to one that is restful to the eye, abstracted shades of rose with floating mechanical elements, like the design of a whimsical, erratic contraption. Marriage yet again, perhaps. People do better with the truth than without it, believes Guralnik, and that is her underlying philosophy throughout. Without the truth, one is either sleeping or guessing and will be plagued by dreams and childhood fears.

In Jonathan Franzen’s recent novel Crossroads, set in the 1970s, the matriarch of the family, a pastor’s wife, seeks counseling from a therapist who occupies a space in a suite of dental offices, and in their waiting room she has “seen patients emerging from the clinic with expressions more distraught than dental work could account for.” That one is going to undergo a painful procedure without anesthetic is not necessarily what Showtime’s set prepares one for. Guralnik’s immaculately designed office is both austere and invitingly warm. The Architectural Digest–ing of the sets of upper-middle-class drama has been escalating for some time now; the fictional office of Bob Newhart, who played a psychologist in a 1970s TV sitcom, is not a patch on Guralnik’s, and hers is actual—or at least a replica of the actual—as is that of Virginia Goldner, her unflappable supervisor, whose space is full of light and orchids and lithe table sculptures. The visits with Goldner are helpful for expanding the interior spaces as well as adding a layer of meta-narrative as Guralnik debriefs with her (which is something she does in real life).

Within Guralnik’s office, however, there is much controlled agony. Few of the people sitting on the couch avoid the cliché of one person (a man) playing fruitlessly with a plastic puzzle while the other speaks tearfully and avails herself of a Kleenex box. In season 1, there is literally a Rubik’s cube, and no one ever solves it, an unfortunate but apt metaphor. During one session, when the cube has been placed out of reach, one of the husbands gets up to look for it, finding it on a shelf. All of the couples seem somewhat aware of themselves as performers in a reality show. But their ownership is like a time-share: the show is only partly theirs, but when it’s theirs they seize it. The cameras are not obtrusive, and no one is cripplingly shy.

Season 1 begins with four relationships. The first one, Annie and Mau—the most strikingly actorish and emotionally enigmatic of the couples—have been married for twenty-three years. They have a tendency to quibble, and he is a handsome mansplainer. “Do you see how quickly you move to devaluation?” Guralnik asks him. “I think I don’t care how quickly I move to devaluation,” says Mau.

There are apparently things Annie believes are off-limits for discussion, which keeps Guralnik feeling out of the loop. They are the only couple that cause her to glare. The word-parsing Mau, who resembles the actor Clive Owen, has come from a childhood of poverty, violence, and neglect (though he does not view it as abuse), and now wants merely to be seen in his entirety without having to indicate who he is. This is an exaggerated form of a condition common among the couples—the desire to be known and accurately acknowledged without having to spell things out for their partner.

As an example, Mau sees himself, he says, as a person who would like a “glass of water and [to] have it there before he asks.” This hunger for magic is how he has gotten through life, he claims. “I don’t have complicated needs. I’m utterly transparent,” he insists. But he sees his birthday as a test of how well his wife knows him. And she usually fails. Guralnik finds the two of them both mystifying and codependent.

Advertisement

“This marriage will keep its peace if she gives up on a certain piece of her subjectivity,” she says to Goldner. But Annie is counting the years until their fourteen-year-old son is old enough for her to leave the marriage. Children are often the off-screen factor keeping Guralnik’s couples together.

The other three couples in the show’s first season exude touching vulnerability in the sessions and, despite some flashing anger and watering eyes, bring determined self-awareness and emotional intelligence to their troubled situations. They are strong people with wounded pride, and the therapy sometimes involves isolating the wound from the pride. The tasks Guralnik sends them home with—take two hours to yourself; make him cook dinner; express affection; listen, listen, listen—are mostly accomplished as the months roll along. The balance between togetherness and solitude, attention and boundaries, trusting but verifying, needs to be figured out for everyone.

All but Annie and the stubborn, self-educated Mau appear willing to “do the work” that psychotherapy requires (most of it a conscious breaking of one’s own unhelpful habits). As for his own “incredibly warm, sweet, vain, and thoughtless” mother, Mau says insightfully, “If you ask my siblings they’d all agree that we’re all waiting for her to take us to the pool thirty-five years ago.” In marriage the past lands in the present as a time capsule; in his marriage, Mau is still waiting for his mom.

The second couple we meet in this first season are Lauren and Sarah (Lauren is trans and recovering stoically from difficult surgery). They are the most impulsive of the couples, having moved in quickly, married quickly, then sexually opened up their marriage, and then tried for children. Guralnik’s task is to slow them down. Money and the division of labor, issues common to many households, also make appearances in Lauren and Sarah’s conversation. Lauren doesn’t like dishes in the sink but admits that, because she makes more money than Sarah, she believes that maybe Sarah should do them. Plus ça change.

The couples on the show are selected to demonstrate a range and diversity of racial, sexual, ethnic, religious, and social class suffering. Those who laugh with each other give the viewer the most hope. The ones who can eventually see that immersive professional work is not the enemy of a happy family—as so many commercial Hollywood films have repeatedly told us through the decades—also seem to be on the right track. As the credits roll at the end of every half-hour episode, the music suggests a theme for each of their stories. One episode ends with the Soul Scratch song “The Road Looks Long,” and in it are flung and sung all the unreasonable hopes and dangers of the marital project. One feels precisely what the singer means when he says, “Just give me a little faith…Ain’t got much going my way.” But everyone on Guralnik’s couch manages at least one smile.

Who wouldn’t root for these couples? Though why we do touches on our own fear of aloneness as well as our belief, expressed in everything from Shakespeare to Mamma Mia!, that the preferred human narrative is one that ends in an enduring marriage—that is, one that can be endured.

The therapist is, of course, at the center of this collection of unplotted domestic tales: she is the constant and the guide in the ramble, there to help the couples deepen their understanding of their dilemmas—“nothing more,” advises Goldner. A deeper understanding of the trouble always sounds like a good idea, but is it? The therapist is not to offer an opinion as to whether the couple should break up, even if she has one. She is not to side with any desire to end things. (They can, if they choose, end things without her help.) “I feel like I was siding with the giving-up,” Guralnik says to Goldner, about Evelyn and Alan, a gentle, teary Latinx couple who exude almost unbearable unhappiness. But Guralnik does not give up, and Evelyn and Alan do as they are told. Guralnik is able to crack the case by getting Alan to reexamine his habits of checking out and living solo in the world. Soon Evelyn and Alan are meditating together at home and the marriage looks as if it’s been pulled from the ditch. “I feel I have such power over them,” Guralnik says, but she uses it well.

Although she feels “the limits of how much [any] relationship can deliver,” Guralnik is there with all of her patients, to rejoice calmly and with affirming declarations when any couple reaches a sense of unbreakability while also abandoning destructive patterns. At that point, they curtail therapy with her—perhaps because they feel they’ve achieved all they can; perhaps only because their medical insurance has run out, though the series does list a medical insurance provider in the credits—and she is left with the intensity of their situations (addiction, abuse, fatal inertia, insufficient love, job issues). Her occasional worries that her work with them might be both meager and futile seem to reveal themselves in anxious expressions on her face, but her successes also leave her bereft. She has become involved. “Suddenly the enormity of their stories is just sitting with me,” she tells Goldner. She is not as detached as she might wish. “What a bizarre profession,” she confides to Goldner in the season 1 finale. In the end, she is alone on the set, the clientele having gone home. A new cast will arrive shortly.

Season 2 introduces three new couples: two gay white men (Gianni and Matthew) and two straight couples, one interracial (Dru and Tashira), and one Orthodox Jewish (Michael and Michal). The gay men must deal with Gianni’s homesickness for his old dance troupe and for his native Italy, as well as with Matthew’s alcoholism; the devoted Dru and the reluctant Tashira must deal with unequal affection; Michael and Michal must deal with unequal ambition. The season begins just before the pandemic, and so, as it proceeds, it includes all the domestic suffering of the quarantine: unemployment, exhausting childcare, social isolation, Zoom. Sheltering in place often forces each member of a couple to give up whatever exit fantasy they may harbor, or, on the other hand, to nurture it in silence and deferment.

The counseling for a while is forced to go online, which makes everyone’s home life seem funkier and blurrier. Guralnik sits in front of a jammed bookcase with Bleak House prominent on one of the spines above her head—a witticism. We imagine that we get a glimpse of what time-tested love resembles from the inside—the pets, the kids, the chores. Goldner, however, appears to have a calming country retreat, the series’s quick nod to class disparity in the pandemic. No toddlers burst in squealing. Pastoral springtime dapples her windows.

Luckily for the clients, the virtual is only temporary, and soon the couples are returning to Guralnik’s office and her new pink print in the waiting room. Summer both heralds their return and closes out the sessions of season 2. Lessons have been learned: a couple must share anxiety, passing it back and forth between them until it is understood; a partner must smile fully or it may resemble a smirk. Guralnik has been patient and seemingly effective; the couples give her affectionate good-byes as well as gifts to say thank you and farewell.

“It’s hard to let them go,” she says to Goldner. “Are they going to mess up the work we’ve done? ‘Don’t mess it up!’” Though she may feel abandoned (“I’m left with this void,” she confesses), this is her territory—starting over with a new set of problems—and she is good at it: unknotting the discourse, excavating the past, naming emotions (most of them forms of sorrow). “That’s sabotage,” she will say, or, “If that’s the dynamic, why go there?” (The one time I was in couples therapy, the therapist turned to me and said, “And now I have a question for Lorrie: Where did you get your boots?”) Since the series began, it has been almost impossible for new couples to get an appointment with Guralnik: she is completely booked.

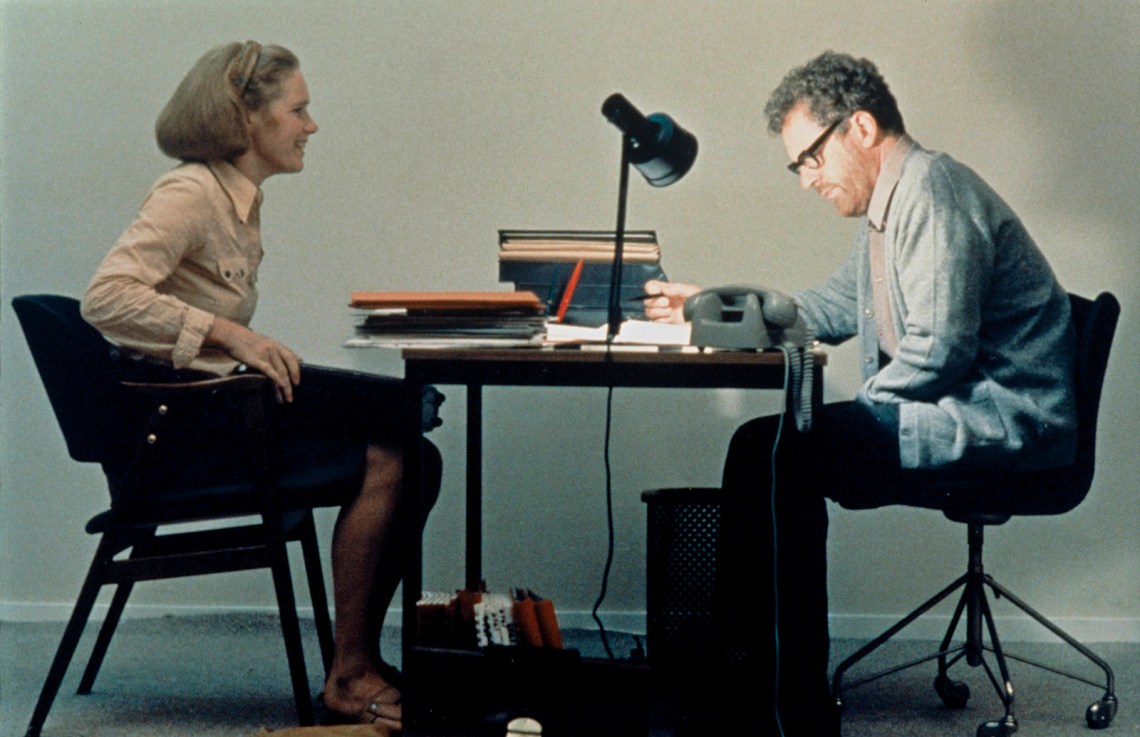

This glimpse of successful couples counseling is interesting to compare with the recent HBO drama Scenes from a Marriage, which, despite the dissolving relationship at its center, has mostly disparaging comments in its script regarding the “psychobabble” of professional therapy. Psychotherapy here is offstage, referred to but not participated in jointly. Hagai Levi, who created the original Israeli television series BeTipul (In Treatment), has put together an honoring reassembly of a modern classic, the famous 1973 Ingmar Bergman television series, a program that is said to have prompted a spike in divorce in Sweden in the mid-1970s.

Levi’s Scenes from a Marriage is slightly more alert than Bergman’s to the theater of couples talking, even if not in therapy, and the performances by Jessica Chastain and Oscar Isaac are harrowing in their concentration and intensity. Their scenes are like a postgrad theater workshop (and indeed the two actors attended Juilliard together). Perhaps Levi’s script (written with Amy Herzog) is neither graceful nor cogent, but if you want to see unchecked and destructive feelings running around a room, this is your show.

I have seen Isaac be brilliant before (Inside Llewyn Davis, Show Me a Hero), but I’ve not seen Chastain in any screen role go so deeply mad with fury, despair, and confusion. When, in the opening scene, her face is presented scrubbed clean of make-up, it possesses the girlish glimmer and fleetingly jolie-laide aspect of Liv Ullmann’s, though not as much as Michelle Williams’s would have (Williams was also considered for the part). But in several later scenes Chastain’s character quickly becomes unhinged in a way that is not of a piece with the rest of the show. Her performance is not unpersuasive, just viscerally startling in a manner that offsets the glamorous movie-star sheen she sometimes has trouble shaking loose from her screen work.

Neither series has a conventional plot: each consists of scenes enacted around events, roughly one event per episode: an abortion, an infidelity, a separation, the loss of a job. The emotional hairpin turns of Chastain and Isaac involve more whiplash than the lower-key performances of Ullmann and Erland Josephson in the Bergman original, though in this new rendition Isaac has the Ullmann part of the betrayed partner and Chastain the role of the inscrutable wayward spouse.

Sexual dysfunction is a motif of the marital conversations in the Bergman narrative, and the book the husband unsexily reads at night in bed is Albert Speer’s memoirs. The sexual drama in Levi’s series is different and involves the husband’s youthful religiousness and inexperience juxtaposed with the wife’s lifelong habit of adventure. In both versions, the characters’ garden-variety selfishness and emotional illiteracy are tricked out with weighty and expert acting.

Neither show judges its couple, since it is not the married people who are to blame but marriage itself: Bergman and Levi land on a conclusion that is the opposite of Couples Therapy’s premise that marriage is something worth managing and saving. In Scenes from a Marriage, the institution is toxic with expectations. Why should a person have to be all things to a partner? “At work I see people who collapse under the weight of unrealistic emotional demands,” says Bergman’s Marianne, a family lawyer. “I find it barbaric.” Her husband, Johan, a professor, agrees: “It’s a ridiculous convention passed down from God knows where. A five-year contract would be ideal. Or an agreement subject to renewal.” Marianne adds, “I wish we weren’t forced to play all these roles we don’t want to play.”

Levi’s series, unlike Bergman’s, breaks the fourth wall by showing us the actors arriving at and departing from the set, emphasizing that the house is not a home but a stage. Bergman broke the fourth wall in The Magic Flute and Persona—is not marriage also an opera (The Magic Flute), as well as a psychological horror show of obscure but incessant doubling (Persona)?—but he was wise not to do it in his television show. In Levi’s Scenes the broken fourth wall is often uselessly spell-breaking and mildly ostentatious. Marriage is a performance of an internalized script! Levi’s choice announces, but the show’s ideas are often more complicated than that. (The very different backgrounds of the spouses, for instance—one religious and orthodox, one not—shadow them quite powerfully.) The crashed fourth wall, however, does offset the claustrophobia of the couple’s house and of the limited number of locations employed in the filming, due no doubt not just to Bergman’s similarly confining spaces in the original but to filming in the pandemic.

Both versions of Scenes from a Marriage begin with the couple’s being interviewed for someone else’s research project on married couples. Levi tracks Bergman’s series in small and large ways throughout. His husband and wife are named Mira and Jonathan, after Bergman’s Marianne and Johan. In both series, the couples sit on green velveteen sofas to answer the researcher’s questions; both wanly mime their doomed self-satisfaction for the interviewer. Both later have dinner with another couple whose marriage is disintegrating, and the viewer is asked to consider whether marital unhappiness is perhaps contagious. Later, both women pull a white sheet up over their faces to hide their weeping after an abortion. In both series, the marital homes become characters and exert their crushing, haunted airlessness, as well as their eventual sentimental ability to renew. The attic and storage spaces, oddly though symbolically, constitute the sites for a rendezvous.

Both series leap months and years in a forward rush through time that neglects to age the characters. In the final episode of each, one spouse has a nightmare of reaching for family members and having no hands, only stumps. Marriage cannot succeed, say both of these shows, because it begins in blindness. It is not the right human arrangement. And in both narratives, only after the couple is divorced can they resume their relationship with true friendship and affection—though even then it necessitates lies, for they are each being unfaithful to another in rekindling their old love. Adultery, not marriage, is the true relationship, because it’s the free condition, the unburdened, private, assertive, unobliged, and unobliging thing, both series rather pessimistically insist.

The vision Levi serves (in both senses of the word) is Bergman’s—one of radical and free detachment from institutions. One could get into the weeds and say it is a masculine vision, or certainly a male artist’s. But it is interesting to see Levi give this idea (a tad unconvincingly) primarily to Mira, the wife character, who remains unpredictable and obscure. Mira rejects so much—including therapy—that it is difficult to know what she would like. A glass of water, perhaps, without having to ask. Mind-reading, once more, would be useful for everyone.

Which is why it is nice to have Orna Guralnik around. The optimistic arc of Couples Therapy is a tonic. Couples have to speak the same language, says Ullmann’s Marianne, early in Bergman’s series. There can be “majestic silences,” she says, but “sometimes all you get is the vast silence of outer space.”