The annual congress of the Latin American Studies Association (LASA) is usually a staid affair, but this year’s was rocked by controversy. In early May, two weeks beforehand, Guillermina De Ferrari, a professor of Caribbean studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, posted a petition online calling on LASA’s leadership to publicly condemn human rights violations in Cuba, specifically the escalating repression of dissident artists and intellectuals. LASA, the most important organization of Latin American studies in the hemisphere, does occasionally comment on political affairs in the region: as I write this its website includes a statement criticizing violence against protesters in Colombia. But instead of siding with the petitioners, LASA’s subcommittee on human rights and academic freedom issued a statement denouncing US sanctions against Cuba, characterizing them as undermining a sovereign nation—a position in lockstep with that of the Cuban government.

LASA’s refusal to condemn Cuba’s human rights violations provoked outrage. Several petitioners declared that they would resign from the organization, which is crucial for securing academic positions, publishing contracts, and professional advancement for junior scholars. Three research centers at Harvard that lead a consortium of universities engaging in academic exchanges with Cuba published a joint statement against the Cuban government’s repression of artists and activists. The confrontation was just the latest indication of the extent to which long-standing US–Cuba tensions affect the study of the country’s history.

Scholars from the US who want to do research on the island about the revolution often find themselves in a bind: gaining access to archives is subject to approval by Cuban state security, and one’s work is constantly subject to scrutiny by authorities who wield the power to prevent anyone from seeing records and people. Scholars and journalists who cross the line by meeting with dissidents or criticizing state policies face expulsion. This often leads to self-censoring caution and euphemistic language, rather than candor about the Cuban state’s authoritarian practices.

The Mexico-based Cuban political scientist Armando Chaguaceda notes that the Cuban government uses the same “sharp power” tactics as Russia and China, exploiting institutions and the press in democratic nations to soften its image abroad. This enables Cuba to benefit from the sympathy of foreign correspondents and academics; their research in turn bestows political legitimacy on a government whose record on human rights and press freedoms ranks very low globally. Cuban studies scholars also face pressures in the US, in that LASA’s stated goals—which include “strengthening scholarly relations between the US and Cuba” and “facilitating the integration of Cuban scholars…in LASA Congress programming”—make critical analysis of Cuba’s governance unwelcome.

It is in these charged circumstances that two new books about the Cuban revolution’s early years have appeared: Michael J. Bustamante’s Cuban Memory Wars and Elizabeth B. Schwall’s Dancing with the Revolution. Both propose to tell stories about the revolution “from within,” which is to say about how Cuban citizens enacted the social, political, and economic transformation of their country. Both strive to present the actions—especially the creative work—of Cubans as evidence of their unhindered choices. This approach is meant to offset histories that focus on statesmen, and to counter anti-Communist views of Cuba as a place where ordinary people have no political voice.

Bustamante, a professor of Cuban and Cuban-American studies at the University of Miami, focuses his research on disputes over the history and legitimacy of the Cuban revolution. In Cuban Memory Wars, he examines news stories, political speeches, cartoons, films, and television shows spanning three decades to demonstrate that the lines dividing revolutionaries from their adversaries have not been as fixed as one might assume from a cursory review of official histories of the revolution. Making good use of old clippings in the Cuban Heritage Collection at the University of Miami, he highlights how political loyalties shifted constantly in the first years after the triumph of the 1959 revolution.

Bustamante also draws on island-based collections relating to political trials in the 1960s and TV shows from the 1970s designed to heroize the country’s counterintelligence operations and persuade Cubans that they lived under constant threat of an American invasion. Yet despite the great range of materials he draws on, he leaves out the full diversity of Cubans: Bustamante admits that his study does not take into account the concerns of Cuban women, gays and lesbians, or people of color, though they make up half the population. So we are essentially drawn into a debate among educated white men about how Cuba should be run, who should do it, and why.

The opening chapter of Cuban Memory Wars focuses on the scramble among various political factions to define the meaning of the new revolution in the three years before Castro declared it socialist in 1962. In 1952 the former president, Fulgencio Batista, had staged a coup, ushering in a military dictatorship and escalating violence against opponents. Castro led an unsuccessful attack against Batista in 1953 and spent a year in prison, after which he went to Mexico to form a rebel group and returned in 1956. His guerrilla army, based in the Sierra Maestra mountains of southeastern Cuba, together with urban movements of various political persuasions, fought to topple Batista, who fled at the end of 1958 after the United States withdrew military support. Bustamante provides ample evidence that—contrary to the prevailing assumption that Castro and his bearded rebels single-handedly transformed Cuba—the ousting of Batista was a group effort involving anti-Communist nationalists, student organizations, and vast swaths of the island population incensed by the violence of Batista’s police forces.

Advertisement

Avowed Communists, with ties both to organized labor and to Batista, joined the revolutionary effort quite late, in 1958. By 1962, however, Fidel had secured military aid from the Soviet Union and shut down all the publications that had once aired a range of critical views. Many Cubans who had imagined themselves to be part of a new order left the country as the Communists assumed central positions in government. In Miami, the exile community became increasingly fractured as anti-Communist nationalists, devout Catholics, and disenchanted former rebels were forced to mingle with the Batista supporters who had been their enemies.

Bustamante’s account of the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion (referred to in Cuba as Girón) focuses on how it enabled Castro to consolidate power as the country rallied to defend itself, to justify the militarization of daily life on the island as well as the new alliance with the Soviet Union, and to solidify the view that the Cuban revolution was the culmination of an anti-imperialist struggle against the malevolent giant to the north. Interested in how the state presented the invasion to Cubans, Bustamante looks closely at transcripts of the televised trials of the captured invaders, the 1,400 CIA-backed Cuban exiles who were eventually traded for the equivalent of $53 million in medicine and canned food. Several of the captured insurgents who testified had participated in the fight against Batista alongside those who jailed them in 1961. The trial, televised over five days in late April, just after the attempted invasion, gave them the opportunity to share versions of history that diverged from official accounts—while islanders watched.

Bustamante suggests that this fleeting exposure to the anti-Communist point of view constituted a breaking of taboos. “In real time,” he writes, “the exile prisoners’ interjections into their interrogators’ lines of questioning disrupted rather than reinforced any easy partition between Cuba’s prerevolutionary elites and its deserving socialist citizenry.” It seems improbable that islanders would have been much affected by hearing discordant views about Girón: they had just been obliged to take up arms to defend their country, and they knew of the arrests of thousands of suspected counterinsurgents and the expulsion of Catholic priests. That a variety of positions may have existed for a brief moment does not represent pluralistic debate or guarantee the right to hold opposing views.

In the 1970s, Bustamante argues, the majority of Cuban exiles gave up hope of returning to Cuba and began to adapt to life in the United States. He treats the PBS sitcom ¿Qué Pasa, USA? (1977–1980), the first bilingual sitcom in the US, as an accurate reflection of this assimilationist turn in Cuban exile family life, writing that “the show treated the ‘Cuban Americanization’ of the quintessential Cuban immigrant household not as a liability but as nature’s course.” But given how many exiles retained the Spanish language, married inside the community, and considered US policy toward Cuba central to their American voting preferences, I am skeptical of his claims that most of the community assimilated quickly—exiles made Miami more like Cuba rather than making themselves more like Americans. An important film that counters his assumption about Cuban exile assimilation is El Super (1979), the first independent feature made by exiles Leon Ichaso and Orlando Jiménez Leal. It offers a far bleaker view, telling the story of a homesick, uprooted Cuban living in a Manhattan basement, toiling as a superintendent, getting trapped in repeated conversations about the Bay of Pigs invasion, and struggling to understand his Americanized daughter.

Bustamante contrasts what he sees as the assimilation of Cuban exiles with the political activities of two small Cuban-American student groups, Abdala and Areíto. These groups diverged from the dominant political stance of Cuban exiles in advocating for direct involvement with the Cuban government. He notes that these groups were made up of young people who arrived in the US as children, some on the CIA-backed Peter Pan flights of the early 1960s, though all of them felt the decision to leave Cuba had not been their own. The short-lived Abdala group was primarily active in New York City and New Jersey, and is most famous for its 1971 act of civil disobedience, in which sixteen members chained themselves to chairs in the UN Security Council chambers and demanded a meeting with officials to discuss political prisoners in Cuba. Areíto published a magazine about Cuban society and the revolution’s accomplishments. The groups’ acceptance of Cuban socialism and their pro-rapprochement stance contributed to the opening of visits to the island for thousands of exiles in 1979, which had significant consequences for both Cuba and Miami.

Advertisement

Bustamante’s account of these family reunification visits is the only part of the book that relies heavily on interviews, and as a result this section is the most rich in telling detail, most of it contradictory. Between 1979 and 1982, for the first time since the revolution, about 150,000 exiles were allowed to return to the island to visit relatives for up to two weeks. Those who visited were charged exorbitant fees for Cuban passport renewals, hotels, and airfare, but this did not stop them. The Cuban government found itself compelled to change its tune about the people it had once called “scum” because it needed an influx of hard currency.

Bustamante quotes a contemporary interview with an eighteen-year-old named Ernesto Hernández—“I would not go as long as Fidel Castro is over there”—as “typical of the majority, young and old, who equated travel to the island with lending support to the Cuban government.” The islanders who had refrained from communicating with exiled family members out of fear of reprisal were suddenly interested in them, and the gifts they brought, despite years of indoctrination against capitalist materialism.

The profoundly emotional nature of family visits, as well as the political maneuvering they involved, make it hard for me to understand how Bustamante can argue that the reunification flights did not yield any visible response in Cuba: “Whether in relation to family reunions joyous and fraught, or the jealousies engendered among friends who did not receive gifts from Miami guests, the island’s public sphere (to the extent that one existed) was mute.” Yet stores in hotels became stocked with consumer goods that no tourist was likely to buy for themselves; to this day many locals linger outside shops and dream up shopping lists. The Cuban writer Jesús Díaz made a movie about this national drama called Lejanía (The Parting of the Ways)—not mentioned by Bustamante—that was named the most important film of 1985 by Cuban film critics.

While Bustamante uses many types of cultural artifacts to illustrate political attitudes, Elizabeth B. Schwall’s new book, Dancing with the Revolution, focuses on dance and its relationship to the Cuban state, from the 1940s through the first three decades of the revolution. A visiting lecturer in Latin America and Caribbean history at Berkeley, Schwall concentrates on ballet, modern, and folkloric dance, charting how a handful of highly influential proponents of each form created world-renowned ensembles, cultivated audiences at home and abroad, and allied their endeavors with the political agendas of the Cuban state. She notes how a Eurocentric attitude that still prevailed on the island after the revolution meant that ballet received more funding, better facilities, more access to international tours and dedicated television programming than modern or folkloric dance.

Schwall writes somewhat reverentially about the ballet star Alicia Alonso, who used her international fame to forge alliances with Batista and then switched over to the revolutionary cause in the late 1950s, securing exceptionally high funding from both sides. A Communist Party member since the 1940s, she was a shrewd dance promoter: in 1948 she founded Cuba’s first ballet company and named it after herself, though she later changed its name to the Ballet de Cuba and, in 1961, to the Ballet Nacional de Cuba. Ultimately Alonso ensconced herself within the upper echelons of the revolutionary power structure in a way that only a handful of cultural arbiters—such as Cuban Film Institute founder Alfredo Guevara and Casa de las Americas founder Haydée Santamaría—ever managed.

Schwall cannot ignore the extraordinary political influence that Alonso enjoyed, and acknowledges that the American expatriate Lorna Burdsall, a leading proponent of modern dance in Cuba, was married to Manuel Piñeiro, the first director of Cuban Intelligence and mastermind of Cuba’s secret operations in Latin America. (Burdsall also befriended Mariela Castro, the daughter of Raúl Castro and niece of Fidel Castro.) These connections afforded ballet and modern dance obvious political advantages, yet Schwall insists that ordinary dancers were the central force propelling their art form to its privileged relation with the state.

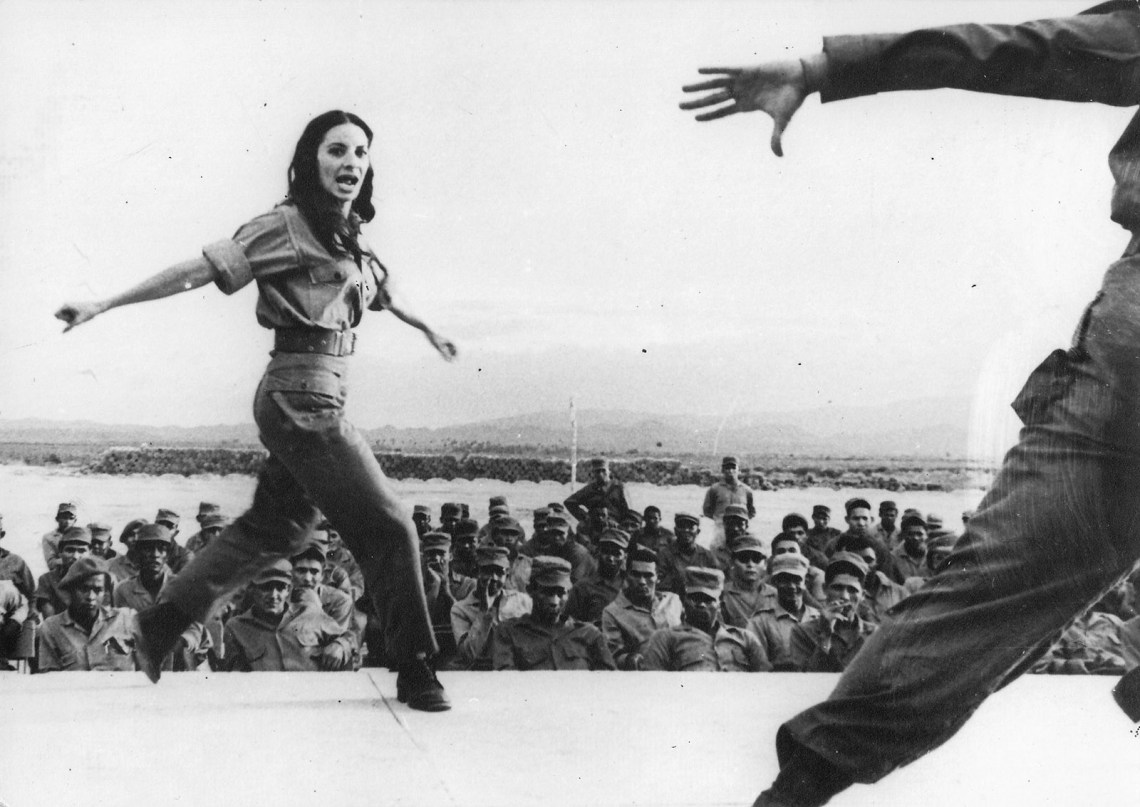

When Schwall discusses the post-1959 era, her account is skewed by her desire to present the revolution as a democratizing force and dancers as both loyal soldiers and forceful advocates for themselves. She goes into great detail about the establishment of dance companies in the early 1960s devoted to folkloric and modern dance, the rapid expansion of dance education, and the strategic recruitment of people of color, which led to notable ethnic and economic diversity in the country’s dance ensembles, even in ballet. Schwall finds evidence of dancers’ militancy at every turn, writing that they “characterized their art as embodiments of revolutionary politics.”

She describes the work of the choreographer Eduardo Rivero, for example, as a “labor of love…filled with liberating movement and expectation.” She reads political purpose into the work of Black dancers who “took action by performing to distinguish themselves on national and international stages,” which resulted in Afro-Cuban performance remaking “the contours of revolutionary culture.” She argues that Cuban dancers “reaffirmed their significance to revolutionary politics” by touring. But since folkloric and social dance were widely practiced outside the realm of concert dance before 1959, the argument that the revolution somehow made Cubans more aware of their dance culture seems questionable.

The most impressive parts of Schwall’s book appear in her investigation of Afro-Cuban dance forms, the cross-cultural exchange between Cuba and the US, and the challenges that dancers of color faced in the prerevolutionary era. She explains how the island-based ethnologist Fernando Ortiz, the poet Nicolás Guillén, and many musicians and dancers cultivated serious interest in Afro-Cuban culture by celebrating vernacular speech and rhythms and borrowing images and myths from syncretic religions. They laid the groundwork for a range of explorations of folkloric traditions after the revolution, which resulted in the incorporation of rumba steps in certain ballets, modern dances inspired by African sculptures, and dances set in working-class neighborhoods.

Afro-Cuban poetry, music, and dance also caught the attention of the pioneering African American dancer, choreographer, and anthropologist Katherine Dunham, who worked with Cuban performers in New York. Schwall notes that Dunham accepted Cuban dancers of color into her company when they had nowhere else to study modern dance and “influenced Cuban modern dance…before modern dance formally existed on the island.” Schwall’s attention to the collaborations between Dunham, Langston Hughes, Guillén, and famed declaimer of poems Eusebia Cosme sheds light on important African diasporic dialogues that crossed national borders in the early twentieth century. Yet in general, before 1959, African-derived religious dance was made more palatable by featuring light-skinned female performers, and although Black dancers assisted in the creation of ballet steps and scenes drawn from Cuban contemporary urban life, they were erased from the historical record.

Although Schwall notes that performances were censored, dancers’ morality strictly policed, and defections not infrequent, she does not question whether expressions of revolutionary devotion were required to maintain one’s career. When her account gets to the 1980s, she notes that a younger generation had begun to incorporate critiques of the system into their work, yet she never doubts the sincerity of dancers’ “revolutionary fervor” during the earlier period. She seems reluctant to acknowledge that most of those who were critical of the system ended up in exile, preferring to attribute departures to financial need or professional advancement.

Schwall’s attempts to position dancers as revolutionaries and makers of their own destiny grow increasingly strained in her discussion of gender and sexuality. She examines the Cuban state’s campaigns against homosexuals in the 1960s and 1970s and provides details about the three-part strategy that was used to enforce heteronormativity in dance: training boys separately to avoid exposure to feminine gestures, censoring perceived homosexual content, and punishing dancers and choreographers thought to be gay. After several male ballet dancers defected in 1966, “dancers were divided by rank, gender, evaluation of either ‘positive’ or ‘negative,’ and labeled as homosexual…. Ultimately, nine company members, including soloists and technical staff, were not allowed to travel.”

Yet this doesn’t deter Schwall from arguing for the political significance of the modest and often thwarted efforts of targeted dancers. She claims that the declarations of ballet dancers against the persecution of nonconformists who defected in 1966 constitute “evidence of their unique power to take action,” even though their statements were made once they were outside Cuba. She argues that a sexual satire with allegedly queer content “left an imprint” on Cuban culture even though it was censored. Schwall also understates the severity of the sanctions on persecuted homosexual members of the dance community. To suggest that the choreographer and folklorist Rogelio Martinez Furé, accused in the 1960s both of having gay sex abroad and of Black sectarianism, was able to insulate himself from harsher punishment because he remained employed during the 1970s overlooks the political significance of his demotion. Being “reassigned” put him in the same category with “counterrevolutionary” literary figures of the era who were also banned from public life and turned into pariahs.

Throughout the book, Schwall exhibits great concern for how racism affected Cuban dancers’ career advancement. Yet she doesn’t mention that the first film to be censored by the revolutionary government in 1961—PM by Orlando Jiménez Leal and Sabá Cabrera Infante—featured working-class Black Cubans dancing in a portside bar, which was interpreted as a sign of indolence and political disaffection by the leaders of the national film institute.

Schwall does note that Black dancers and religious practitioners received no credit when their knowledge was appropriated by white choreographers, but she pays little attention to the political tensions between the socially marginalized Blacks who worked as advisers for dance companies and state-sanctioned choreographers and administrators. Some of these men, hired for their knowledge of Afro-Cuban spiritual practices, were later interviewed by the ethnomusicologist Katherine Hagedorn, who conducted research in Cuba between 1989 and 2000. They told her that in the 1960s the leadership of the Cuban Folkloric Ensemble cooperated with policing efforts aimed at infiltrating Afro-Cuban religious sects and ferreting out Black men who were not considered “productive” enough—which at the time meant that they were probably not cooperating with volunteer political activities and were thus suspect.

Concert dance had a dual function in Cuba—as a symbol of revolutionary benevolence and as a form of social control—and this becomes most apparent in the contrast between the state’s support of concert dance and its policing of street dance. Schwall describes elitist Cubans dismissing popular dancing—practiced by almost everyone, not only poor Blacks, in bars, in people’s homes, and on the streets—as a vulgar activity of the lower rungs of society. Alicia Alonso disdained it and wanted to prove to the world that Cubans could rise above it. But such denigration of popular dance styles like danzón, rumba, and salsa also provided a seemingly apolitical, aesthetic cover for the policing and repression of undesirables, and Schwall does not address that. She celebrates the revolutionary government’s efforts to bring dance to the masses but fails to mention that popular dances associated with Cuban nightlife and American rock and roll were interpreted as signs of imperialist decadence by the regime during the 1960s and 1970s.

In her epilogue, written in 2019, Schwall makes a brief reference to Decree 349—a law that was passed the previous year—as a rejection of “vulgar” content in artwork, which is the government’s dismissive term for culture produced outside state venues. In fact, Decree 349 empowers the state to penalize artists who share their work with the public without prior authorization—it strengthens the state’s ability to decide who can be considered an artist at all, and has been condemned by international human rights organizations and the European Parliament. The state’s defense of the law recycled its long-standing attacks on self-taught and largely Black rappers and reggaetoneros whose confrontational lyrics appeal to disaffected youth. Socially conscious Cuban cultural workers quickly pointed out the racist implications of the government’s argument and since then have established two independent groups that are challenging the law.

Those groups include artists from several fields, but no dancers. So far, the official position of the Ballet Nacional de Cuba has been to defend the government, not fellow artists. Instead of considering why dancers stand apart from the rising tide of disaffection among Cuban artists, Schwall offers platitudes about the persistence of dance in Cuban life despite hardship. Her exclusive reliance on the Cuban state’s point of view hints at regrettable self-censorship, which is similarly evident in Bustamante’s euphemistic blaming of “archival silence” for preventing us from seeing Cuban society in all “its plurality and depth.” The greatest challenge to understanding Cuban culture lies in grasping the dual function of the state, which supports the same people it represses, and in whose name the revolution came about.