The French philosopher Simone Weil’s two visits to Italy in 1937 and 1938 were among the happiest experiences of her life. “For some years,” she wrote to the young medical student Jean Posternak on her return to Paris in 1938, “I have held the theory that joy is an indispensable ingredient in human life, for the health of the mind.” Absence of joy, she suggested, is the “equivalent of madness.” Shortly before her trip, which began at Lake Maggiore and took in the cultural treasures of Milan, Florence, and Rome, she had been admitted to the hospital for headaches that sometimes struck with such intensity that she wanted to die. “Joy” is perhaps not a word most readily associated with Weil. On the other hand, the epithet of “madness” has constantly trailed her, mostly coming from those who could not fathom her, including Charles de Gaulle, who came to know of her through the papers on resistance that she wrote in London in the last year of her life.

And yet it is central to Weil’s unique form of genius that she knew how to identify the threat of incipient madness for the citizens of a world turning insane. A straight line runs through her writing from the insufferable cruelty of modern social arrangements—worker misery, swaths of the world colonized and uprooted by “white races,” force as the violent driver of political will—to the innermost tribulations of the human heart. What would it mean, under the threat of victorious fascism, not to feel that you might go crazy?

During the course of her Italian visits, Weil encountered several Fascists, one of whom stated, in response to her outspoken antifascism, that her “legitimate and normal” place in society would be down a salt-mine. Weil reacted to the suggestion with something akin to glee. Surely, she wrote, that would be less suffocating than the political atmosphere aboveground: “The nationalist obsession, the adoration of power in its most brutal form, the collectivity (Plato’s ‘great beast’), the camouflaged deification of death.” Likewise, France on the eve of World War II was living in an “unbreathable moral atmosphere” as it fought against the ignominy of demotion to a second-class power, while still “intoxicated” by Louis XIV and Napoleon, who believed himself to be an object “both of terror and love to the whole universe.”

“An incredible amount of lying, false information, demagogy, mixed boastfulness and panic” were the consequence of the deluded public mood. She could be describing the UK in the throes of Brexit, or the US faced with the ascendancy of China, as they each struggle to stave off a similar fate. For Weil, such laments are misplaced. “Freedom, justice, art, thought, and similar kinds of greatness” are not the monopoly of the dominant nations. Far from it. Think small—one of her favorite words was “infinitesimal”—if you want to create a more equal and peaceable world. “French sanity,” she concluded, “is becoming endangered. To say nothing of the rest of Europe.”

Weil is best known as a political philosopher, a revolutionary trade-union activist, a mystic who devoted her last years to the search for sacred truth, and a Jew who turned to Catholicism, rejecting her heritage. She was also a classicist, a poet, an occasional sculptor, and the author of an unfinished play. “Why,” she proclaimed, “have I not the infinite number of existences I need?” She was haunted, she wrote, by the idea of a statue of Justice—a naked woman standing, knees bent from fatigue, hands chained behind her back, leaning toward scales holding two equal weights in its unequal arms, so that it inclined to one side. Despite the weight and weariness, the woman’s face would be serene. As so often in Weil’s writing, it is almost impossible not to read this image as a reference to herself, although her political and moral vision always looked beyond her own earthly sphere of existence, which she held more or less in steady contempt. She may have been sculpting herself in her dreams, but her template was universal. Justice was for all or for none.

The fact that Justice was a woman was not incidental. According to Simone Petrément, her biographer and one of her closest friends, Weil’s mother told her that killing to prevent a rape was the one exception she made to the commandment against murder. Much later, she took the image of a young girl refusing—with an “upsurge” of her whole being—to be forced into prostitution as the model of a true politics. Antigone and Electra were Weil’s heroines, both belonging to the Greek lineage in which she sourced the cultural values she most cherished in the modern Western world. (She translated central passages from Sophocles’ plays.) Antigone in particular she returned to at the end of her life, for her appeal to an unwritten law that transcends natural rights—which, as she saw it, always sink to the individual claim. The Greeks, she insisted, had no notion of rights: “They contented themselves with the name of justice.”

Advertisement

As Robert Zaretsky recounts in his recent life study, The Subversive Simone Weil, Albert Camus was one of the earliest devotees of her writing. In a special issue of the Nouvelle revue française dedicated to Weil in 1949, he described justice as the principle to which the whole of her work was “consecrated.” (He recognized that for her, this had been a spiritual calling.) Justice, then, should “surely guarantee her a place in the first rank,” a prize that she had so “stubbornly refused” when alive. Camus did all he could to fulfill his own prediction. As editor of the series Espoir at Gallimard, he published seven of her works, tracing the arc of her writing from La condition ouvrière, her acclaimed account of the human degradation of factory work, which she experienced firsthand in 1934–1935, to her final extended essay, The Need for Roots, a meditation on the evil of displacement precipitated by her own exile from France during the war.

Her output was prodigious, and she never stopped writing even though, apart from a scattering of essays, not one of her works appeared during her lifetime. She was convinced that she would be forgotten, a prospect that did not appear to dismay her. In one of her last letters to her parents in July 1943, she wrote of her inner certainty that she contained within her a deposit of pure gold that should be passed on but most likely wouldn’t be: “This does not distress me at all.” Weil was a refugee—she described herself as an exile wherever she found herself. Together with her parents, she had fled the imminent Nazi occupation of France to New York, having first traveled to Marseilles on the last train to leave Paris on June 13, 1940.

She felt she had deserted her people, and almost on arrival in America insisted on going to London in the face of her parents’ objections, in the sole hope of joining the forces of resistance across the Channel. Her final letters, brimming with optimism, kept her parents completely in the dark about her rapid physical decline. In April 1943 she had been admitted to Middlesex Hospital with tuberculosis, from which she had no chance of recovering since she refused to eat any more than the rations her compatriots were receiving in France. “Hope,” she instructed them in one of her final letters, “but in moderation.” She was thirty-four years old when she died.

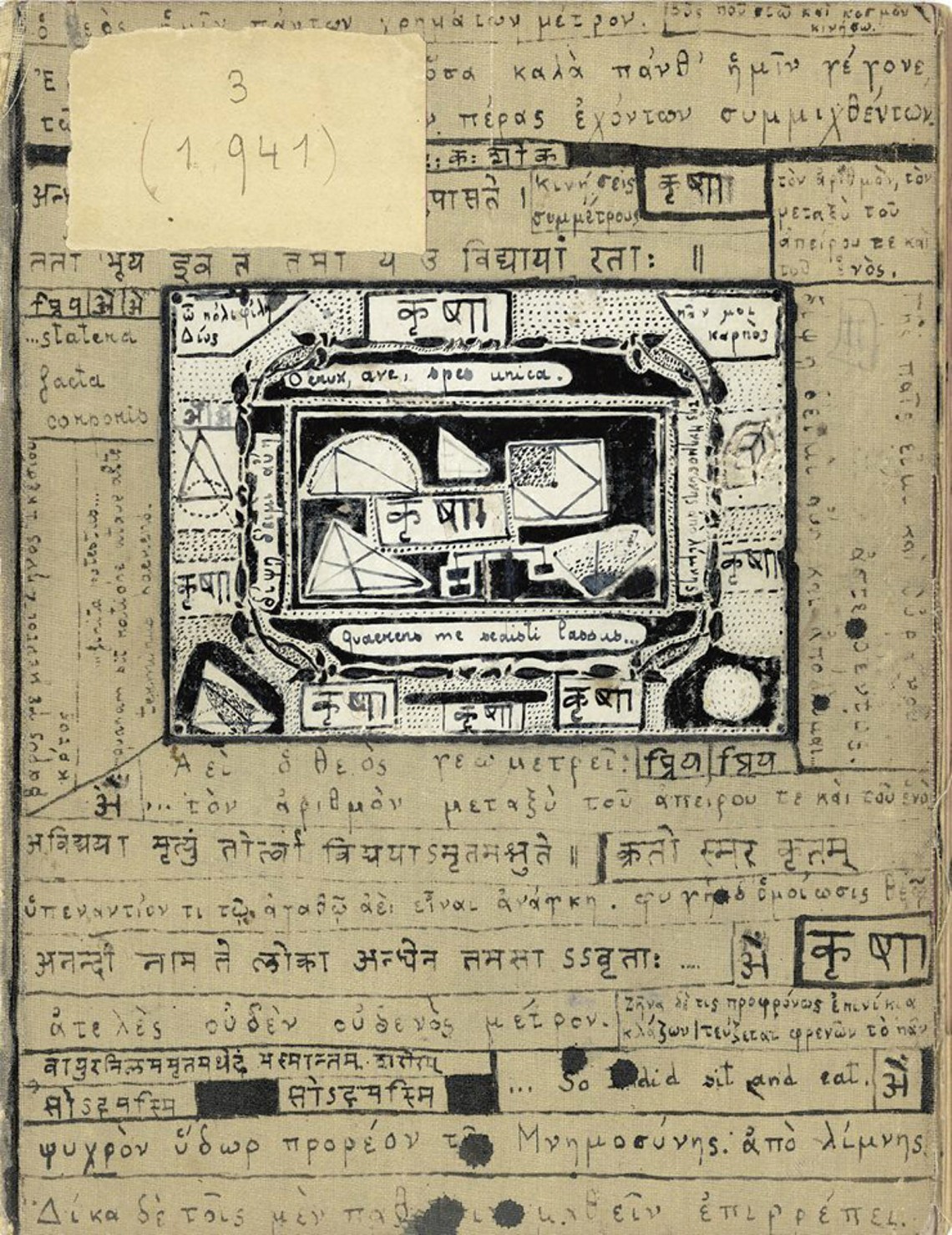

After her death, her parents devoted themselves to a painstaking transcription of her work, including every word of the outpourings of her final months, which contained some of her most important writing. According to her niece Sylvie Weil, born in the last year of Simone’s life, the question of ownership—where the reams of paper should be housed, how they should be published—effectively tore her surviving family to pieces. (Sylvie was the daughter of Simone’s only brother, the distinguished mathematician André Weil.) “You have,” she reproaches Simone in her memoir, At Home with André and Simone Weil (2010), “bequeathed these ruined faces to me.”

As Zaretsky points out, there is no one thread running through her writings, a difficulty he responds to by picking out the five themes he considers most representative of her thought: affliction, attention, resistance, roots, and “the good, the bad, and the godly” (the last referring to her version of mysticism, in which spiritual apprehension was the one true source of a viable ethical life). This has the advantage of focus but, as he is aware, compartmentalizes her ideas, creating distinctions and separations whereas, more often than not, her concepts slide into and out of one another in a sometimes creative, sometimes tortured amalgam or blur. Weil’s writing is like an intricate tapestry with multiple strands—pull on one and it can feel as if the whole thing will fall apart in your hands.

Nonetheless, the absence of “justice” from the list strikes me as a strange omission in what I read for the most part as an informative and attentive book. Weil’s heart was set on justice. It was her refrain. A recurring principle in pretty much every stage of her writing from start to finish, the concept of justice renders futile any attempt—though many have tried—to separate Weil the mystic from Weil the activist, or Weil the lover of God from Weil the factory worker, who felt that the only way to understand the wrongs of the modern world was to share the brute indignities of manual labor, which reduced women and men to cogs in the machines they slaved for.

Advertisement

Weil changed her mind a number of times, most significantly when she repudiated her earlier pacifism after Hitler invaded Prague in March 1939. By then she had also lost her faith in Marxism and in any version of politics grounded in parties and trade unions, or in what she increasingly came to see, from the Hebrews and Romans to Hitler, as the inevitably totalitarian powers of state; her unqualified inclusion of the Hebrews in that list is seen by many as the most compromised and treacherous component of her writing. But on certain matters she never falters. Right to the end, she grappled with the question of how to conduct oneself in the service of a more equitable world. “The Christian (by instinct if not by baptism) who, in 1943, died in a London hospital because she would not eat ‘more than her ration,’” wrote her former pupil Anne Reynaud-Guérithault in her preface to Weil’s Lectures in Philosophy, “was the same person I had known, sharing her salary in 1933 with the factory-workers of Roanne.”

Measuring her food portions served no one, but in both cases Weil was offering up a piece of herself. She was weighing her actions on the scale of justice. Far from being a narcissistic act, as these endeavors are characterized by her critics (serving her own conscience or slumming it), Weil’s work in the factory and on the farm is better understood as her way of anticipating the proposition advanced in 1971 by the legal theorist John Rawls that justice will be done only when humans are willing to envisage themselves—or, in her case, to put herself—in the place of the disadvantaged and oppressed. “Only if you believe your place is on the lowest rung of the ladder,” she wrote in her Marseille notebook of 1941–1942, “will you be led to regard others as your equal rather than giving preference to yourself.” She was not martyring herself. She was demonstrating, in her person, a form of universal accountability. “I envied her,” Simone de Beauvoir stated, “for having a heart that could beat right across the world.”

Weil wanted to be in the thick of it. As a ten-year-old in Paris she had joined a demonstration of workers demanding shorter hours and higher wages; a year later, she was back on the streets on behalf of the unemployed. In the 1930s, while teaching philosophy at the lycée in Le Puy in the Haute-Loire, she organized and led a demonstration on behalf of unemployed workers who had been given the thankless task of breaking stones in the city square. She was charged with incitement and threatened with dismissal from her teaching post. When the committee asked her to explain why she had been seen in a café with a worker, she replied, “I refuse to answer questions about my private life.”

Le Charivari, a Parisian weekly, described her as “the Jewess, Mme Weil,” a “militant of Moscow.” (The episode came to be known as “the Simone Weil Affair.”) According to other reports, the Anti-Christ had arrived in Le Puy wearing silk stockings and dressed as a man. Only the second was true. Weil wouldn’t have been seen dead in silk stockings. She cross-dressed all her life. On one occasion she agreed to accompany her parents to the opera on condition of being allowed to wear a specially made tuxedo. Her mother did her utmost to encourage in her the “forthrightness” of a boy rather than the “simpering graces” of a girl. As a young woman, she signed her letters to her mother, “Your son, Simon.”

Much later, in a letter from New York in 1942, Weil explained to an old school friend, Maurice Schumann, that she sought hardship and danger only because the oppression of others pierced her to the core, “annihilating” her faculties. Action alone would allow her to avoid “being wasted by sterile chagrin.” Today we can only be struck by how far her final plan—to parachute nurses into occupied France, where they would risk their lives in the service of care—mirrors what we have witnessed in hospitals everywhere in response to Covid-19, a new form of global solidarity that has been one of the few positive outcomes of a pandemic that has also laid bare and exacerbated the world’s inequalities. It was this plan, which she held on to passionately till the very end, that led de Gaulle, when he was presented with it by one of her keenest advocates, to dismiss Weil as a madwoman. Struck low by repeated rejection, she felt that she risked dying of grief (a good reason not to rush to classify her death as suicide, as many have done, including the coroner). According to Simone Petrément, no one in London responsible for her care believed that she wanted to die.

A central question that has vexed so much political thought becomes why justice is always so elusive. Weil’s struggle with this question makes her a psychologist of human power. “Everyone,” wrote the Athenian historian and army general Thucydides in lines that she quoted more than once, “commands wherever he has the power to do so.” No one can resist mastery over others, because the alternative—to be dominated—is so wretched. “We know only too well,” the quotation continues, “that you too, like all the rest, as soon as you reach a certain level of power, will do likewise.” (That “you” is generic and aimed at everyone.) Justice requires, before anything else, a laying down of arms, in both senses of the term. It demands a “supernatural virtue,” Weil comments, because, however advantaged you might be, it involves behaving as if the world were equal; “supernatural” therefore suggests both inspired by divine grace and requiring superhuman effort, as if it were almost too much to ask of anyone.

These reflections on power come in the midst of her 1942 text Attente de Dieu, her deepest meditation on God: “The true God is God conceived as all-powerful, but as not commanding everywhere he has the power to do so.” (This makes God the one exception to Thucydides’ rule.) In fact, “God causes this universe to exist, but he consents not to command it.” Through Creation, God renounced being “everything.” To revolt against God because of human misery is to misrepresent God as a “sovereign” or tyrant who rules the world, as opposed to a deity who has laid down his power. It falls on humans to create a better world—a form of freedom, or divine abandonment, or both.

Most often translated as Waiting for God, Attente de Dieu might also be rendered as God’s Expectation; it is God who is waiting for man to fulfill this promise. To do so, he must relinquish the misguided conviction, cherished by the strong, that the justice of their cause outweighs that of the weak. Nothing, we might say, perpetuates injustice as much as the belief of the privileged that their privilege is just. Or, as Weil observes in her Marseille notebook, “the rich are invincibly led to believe they are someone.”

In an unstable world, Weil observes in one of her finest essays, “Personhood and the Sacred,” written during her last months in London, the privileged seek to allay their bad conscience either by defiance (“It is perfectly fine that you lack the privileges I possess”) or through bad faith (“I claim for each and every one of you an equal share in the privileges I myself enjoy”). The second, she comments, is condescending and empty; the first is simply odious. If US conservatism seems unapologetic in affirming the former, British conservatism has historically oscillated between the two. Today the idea of “checking your privilege” has entered the public lexicon, to be met with a barrage of criticism—as if keeping an eye on your privilege somehow made it all OK (hardly what Weil had in mind).

Weil’s concept of “decreation” is undoubtedly her most difficult. In the moment of creation, God shed bits and pieces of himself; this made human beings the debris of a gesture that leaves neither God nor humans complete. In one of the strongest, earliest commentaries on Weil, Susan Taubes, best known for her 1969 novel Divorcing, unravels Weil’s proposition that human existence is “our greatest crime against God.” Man must “decreate” himself in order to restore to God what he has lost. For Taubes, Weil has created a negative theodicy: “The dark night of God’s absence is itself the soul’s contact with God.” Suffering must be intolerable for the “cords that attach us to the world to break.” As Taubes sees it, Weil is finally offering as grave an insult to those who suffer as those who promise they will be rewarded in heaven or that their suffering serves God’s final purpose.

Weil herself knew she had presented the world with a spiritual conundrum that she had failed to solve. “I feel an ever-increasing sense of devastation,” she wrote to Schumann sometime between her arrival in London in December 1942 and her admission to Middlesex Hospital in April 1943, “both in my intellect and in the centre of my heart, at my inability to think with truth at the same time about the affliction of men, the perfection of God and the link between the two.” She was mortified.

In the libretto to the opera Decreation, Anne Carson gives the kinder, poetic rendering of Weil’s dilemma. For her, Weil is better understood as making an erotic triangle between God, herself, and the whole of creation. As Carson cites Weil, “I am not the maiden who awaits her betrothed but the unwelcome third.” In her New York notebook of 1942, Weil compared God to an importunate woman clinging to her lover and whispering endlessly in his ear: “I love you. I love you. I love you.” (Like all mystics, her faith never detracts from the sensuousness of her writing.) For Carson, Weil, along with Sappho and Marguerite Porete, the fourteenth-century French mystic who was burned at the stake, “had the nerve to enter a zone of absolute spiritual daring” in which the self or ego dissolves.

This is just one moment in Weil’s thinking that resonates with psychoanalysis. Weil had taught Freud’s concepts of repression and the unconscious in her philosophy classes at the girls’ lycée in Roanne in 1933–1934. What was “dangerous” (her word) about Freud’s work, she wrote, was the idea that purity and impurity can coexist in the mind: “Thoughts we do not think, wishes we do not wish in our soul” (like “wooden horses in which…there are warriors leading an independent life”). “Are there really in our souls,” she objected, “thoughts which escape us?” It would take some time before she herself would embrace such a radical disorientation of the ego as the only possible spiritual and psychic path to take. “What we believe to be our self [moi],” she wrote, is as “fugitive” as “the shape of a wave on the sea.”

None of this detracts one iota from Weil’s passionate presence in her own life. “If we are to perish,” she wrote in her 1934 essay “Oppression and Liberty,” “let us see to it that we do not perish without having existed.” How, Carson asks, can we square her “dark ideas” with the “brilliant self-assertiveness of [her] writerly project?” “The answer is we can’t.” Carson considers Weil’s thinking, writing, and being as the best riposte to her own afflicted vision. This seems to me to be more consistent with, and certainly fairer to, Weil as I read her than Taubes’s finally uncompromising critique. However bleak the terrain, nothing, she repeatedly insists, must “be allowed, far from it, to reduce by one jot our energy for the struggle.”

At the heart of that struggle was the most fundamental and cherished form of mental freedom, which was currently under threat: “It is often said that force is powerless to overcome thought,” she wrote as early as 1934, before the extent of the danger was fully clear, “but for this to be true there must be thought.” It was the reason why, despite her conversion, she would not enter the Catholic Church, whose concept of heresy she found suffocating. The well-spring of a crushing totalitarianism, she argued, resides in the use of these two little words: anathema sit. She refused to be baptized.

In her “Draft for a Statement of Obligations Toward Human Beings,” which appears to have been one of the last texts she wrote, Weil makes even clearer the indissoluble link between love of God and human obligation. A truer reality beyond and above this world escapes every human faculty except attention and love, but it can be recognized only by those who bear equal respect to all human beings, and “by them alone.” It enjoins on mankind the “unique and perpetual obligation” to rectify “all privations of the soul and of the body likely to destroy or mutilate the earthly life of any human being whoever they may be.” Any state whose doctrine provokes failure toward this obligation in its citizens is subsisting in crime.

This turns love of God into something like a civic task, or at the very least the sole mode of being through which the evils of the world can begin to be understood, let alone redressed. Remember, she is now writing in 1942–1943, in the midst of World War II. Hitler’s Germany is the criminal state she is talking about. But even though the full extent of the Nazi genocide was not yet known, and she does allude at moments to anti-Jewish persecution, her failure at this point fully to acknowledge the extent of that persecution is, by general consent, unforgivable. Weil insisted that she did not qualify as Jewish under Vichy rule, as she had neither been raised or ever identified with the Jewish faith. In response to the Vichy government’s 1940 “Statut des Juifs,” which she derided, she suggested that the best response for Jews would be to assimilate or even disappear. In perhaps her worst moment, she implied that the uprooted Jewish people were the origin of uprootedness in the world, which comes perilously close to making them the cause of their own persecution.

Why, Sylvie Weil asks in her memoir, could her aunt not see how her political fervor echoed the ancient prophets’ zeal? Why was she blind to the glaring affinity between her own politically charged generosity and the core Jewish principle tzedakah, or charity, “a form of justice, a way of restoring balance”? Her paternal grandmother, Eugénie Weil, who had lived by that very principle, was a devout Jew. Sylvie Weil thus corrects the view—more or less the orthodoxy since Petrément’s 1976 biography—that Simone was born into a family of purely secular Jews. In fact, the hostility of Simone’s mother, Selma, toward her mother-in-law was a constant strain in the family, filtering down through the generations. As a young woman, Sylvie smuggled herself into the library on her father’s membership card to devour Talmud treatises, Ginzberg’s legends, and Graetz’s history of the Jews. “You are doing what my sister would have done,” André responds when he finds out, “because she was honest, by and large.”

Despite this dark shadow, Weil’s spiritual journey was far from being an exit from political life and thought. Her encounters with God—in her correspondence and notebooks she talks of three divine visitations—intensify her earthly commitments, for all the ruthlessness with which she detaches them from her Jewish antecedents. If there was a turning point in her thinking, a far better candidate than her mysticism would be her experience at the front during the Spanish Civil War, which is too often dismissed as a bit of a joke because she had to be rescued by her parents when she tripped and immersed her leg in a drum of burning oil, or because, to her credit as I see it, she was useless at aiming a gun.

In fact, she had every intention of returning to the front as soon as her wound had healed, on condition that her solidarity would not require her to be complicit with spilled blood. For Zaretsky this experience hastens her move away from political engagement. Instead, I suggest, it initiates a new level of political understanding. She had already learned from George Bernanos and others of the atrocities being carried out on Franco’s veterans by the insurgents, including the killing of a fifteen-year-old boy who had been offered the choice between death and joining the anti-fascists, which he refused to do, and of a young baker, who was murdered in front of his father, who promptly went mad. All of which led her to recognize fully for the first time the potential for violence, regardless of political affiliation, in everyone: “As soon as any category of humans is placed outside the pale of those whose life has value, nothing is more natural than to kill them.”

According to Camus, the experience inflicted on Weil a “serious wound” that never ceased to bleed. Out of this moment emerges a sustained commitment to confronting human violence in order not to fall prey to it. There is an analogy, Weil insists, between Germany’s treatment of Europe and France’s conduct toward its colonies, which would make victory in World War II hollow unless decolonization—to use today’s term—was the result. “I must confess,” she had written in 1938 to Gaston Bergery, the editor of the weekly newspaper La Flèche, when she was still opposed to war against Hitler, “that to my way of feeling, there would be less shame for France even to lose part of its independence than to continue trampling the Arabs, Indochinese and others underfoot.”

France, like every other nation, had been thinking only of “carving out for herself her share of black or yellow human flesh.” In her 1938 essay on the colonial problem in the French Empire, she suggested that it would not be hard to find a colony ruled by a democratic nation imposing harsher constraints than those exerted by the worst totalitarian state in Europe. This, as she knew, was a scandalous observation when preserving democracy was generally accepted as a central aim of the approaching war. But she was right that a democracy made up of opposing parties had been powerless to prevent the formation of a party whose aim was the overthrow of democracy itself.

For Weil, colonialism was the exertion of force in its purest form, uprooting or eradicating the traditions it meets in its path, destroying all traces of indigenous histories, wiping out communities’ own memories, and then, as the final insult, denying the violence it has wrought. (“Simone Weil anti-colonialist” is the title given by her editors to this section of her collected works.) What follows, in the colonizing nations, is a regime of “ignorance and forgetting,” a whitewash of their own past. The problem, Weil concludes, “is that, as a general rule, a people’s generosity rarely extends to making the effort to uncover the injustices committed in their name.”

Weil is treading on dangerous ground, and not just because of the analogy she makes between Nazism and colonization. (Today, though the connection can be traced back to Hannah Arendt and Frantz Fanon, any such link is routinely met with outrage.) She is describing what psychoanalysis subsequently theorized as the process of projection, a way of ridding oneself of anguish that makes it more or less impossible for people, regardless of what they may have done or what might have been enacted in their name, to shoulder the burden of guilt, whether historical or personal. These lines from her 1942 essay “Forms of the Implicit Love of God,” written on the eve of leaving France, read almost as if they were lifted from the famous Austrian-British psychoanalyst Melanie Klein:

In so far as we register the evil and ugliness within us, it horrifies us and we reject it like vomit. Through the operation of transference, we transport this discomfort into the things that surround us. But these same things, which turn ugly and sullied in turn, send back to us, increased, the ill we have lodged inside them. In this process of exchange, the evil within us expands and we start to feel that the very milieu in which we are living is a prison.

Weil knew the process of projection at first hand. Her headaches made her want to hit others on the head and to besmirch the whole world with her own pain. In a strange and most likely unintended echo of Freud on the death drive, Weil argues that death is the “norm and aim of life.” Only if one recognizes “with all one’s soul” the frailty of human life and the mortality of the flesh, and admits that we are a “mere fragment of living matter,” will we stop killing.

The resonances are as political as they are personal and intimate, not least for nations on the cusp of victory. In her 1940 essay “On the Origins of Hitlerism,” she wrote that “the victory of those defending by means of arms a just cause, is not necessarily, a just victory.” She was pleading with the Allies, when the moment arrived, not to disarm Germany by force. The only way to avoid doing so would be for the victors—“allowing that this is our destiny”—to “accept for themselves the transformation they would have imposed on the vanquished.” (Not, we might say, the customary path taken by nations that win wars.) Weil is proposing a radical identification across enemy lines, which requires each of us to be willing to see ourselves in the least likely or hoped-for place. This is a version of Rawls once more, but now with a psychodynamic gloss and international, military, colonial reach. To mention Beauvoir again, it is Weil’s heart beating right across the globe. Why has this psychodynamic aspect of her politics received so little attention?

In these moments Weil is proposing a new ethic, one that goes far beyond the idea of attention, or being seized by the other, which Zaretsky rightly picks out as one key to her thought. It is more like magical thinking, because, by giving over one’s very being to the wretched of the earth (“pauper, refugee, black, the sick, the re-offender”), you are flipping the natural revulsion humans feel toward misery—natural, that is, for those who have been even minimally spared. You are turning disgust into a willing and tender embrace. “It is as easy,” Weil suggested, “to direct the mind willingly towards affliction as it is for a dog, with no prior training, to walk straight into a fire and allow itself to be burnt to death.” An “upsurge” of energy “transports” you into the other. You lose yourself in allowing the other to be (contrary to power-grabbing, which expands to fill all the available space). In the final analysis, with the odds piled against it, only such a move makes it possible to recognize the fundamental equality and identity of all people, which means it is also the only chance for justice. It is, then, all the more ironic that the one leap of identification she herself seemed incapable of making, the one form of historic empathy she refused, was with herself as a Jew.

Weil was going against the grain of what she believed, at the deepest level, humankind to be. She was also going against the grain of her own experience, her feeling of eternal exile, of being radically unloved and incapable of loving herself. In May 1942 she wrote a long letter to the radical Dominican priest Father Perrin. It was her “spiritual autobiography,” written from the Aïn-Sebaa refugee camp in Casablanca, where she was waiting for her transit to New York. It was an outpouring. Whenever anyone speaks to her without brutality, she explained, she thinks there must be some mistake. He was the first person in her life who she felt had not humiliated her. “You do not have the same reasons as I have,” she wrote, “to feel hatred and revulsion towards me.” “I am the colour of a dead leaf,” she wrote to him, “like certain insects.” Weil’s inspiration is sourced in revulsion, regardless of the love of those who surrounded her, perhaps above all that of her mother, whose love Selma herself acknowledged had been too much for her daughter to tolerate.

Such revealing moments are often read as indicating a level of despair or mental torment that disfigures her judgment. I lost count of the epithets that circulate freely in relation to Weil in Zaretsky’s book, even though he is at pains to temper and on occasion even retract them: “morbidity,” “fetishizing,” “insufferable,” “inhuman,” “exasperating,” “the ravings of a lunatic,” or “cursed by the inability to stop thinking”—that’s just a selection. (How many of these would pass with reference to any male thinker?) Instead, I would argue that it is her abjection, and above all her willingness to know and to accept it as her own, that propel her to the heights of her ambition for spiritual grace, mental freedom, and a fairer world. I, for one, can only marvel at the hill she had to climb.

A final clue as to how she managed it is to be found in Weil’s way with words. I always come away from her work with a sense of her dexterity or even playfulness, as if writing were the one place where she could be most at ease and loving toward herself. By her own account, she is a creature of analogy, starting with perhaps the most vexed of them all—between Hitler and ancient Jerusalem, or Nazism and colonialism. Analogies are deceptive (trompeuses), she wrote in 1939, but they are her “sole guide.” Once you start looking for them, they are everywhere in her work—remember dogs walking into fires, unconscious thoughts like warriors concealed in wooden horses, and God as a clinging female lover. To which we could add a dog barking beside the prostrate body of his master lying dead in the snow, to convey how futile calling out dishonesty and injustice can feel. Or skin peeled from a burning object it has stuck to, in order to evoke the Frenchman forced to tear his soul from his country after the 1940 fall of France. Or freedom of thought with no real thinking, compared to “a child without meat asking for salt.” Nothing exists, Weil states, without its analogy in numbers (her bond with her brother was profound).

Visceral and unworldly, Weil’s analogies push at the limits, giving voice to something painful or something that eludes understanding. God loves not as I love, but as an emerald “is” green. The fools in Shakespeare (notably the one in King Lear), she writes to her parents in one of her last letters, “are the only characters to speak the truth”: “Can’t you see the affinity, the essential analogy between these fools and me?” Analogy is a spiritual principle, since it is only by means of “analogy and transference” that our attachment to particular human beings can be raised to the level of universal love. Weil has often been criticized for the unyielding tenacity of her judgments, but this wrongly tips the scales, ignoring the risks she takes. At her best, Weil contains multitudes; it is a miracle, she insists, that thoughts are expressible given the myriad combinations that they make. In the end, spiritual, ethical, and political generosity require you to reach, without limits, beyond yourself. I can think of no other writer in the Western canon who pushes us so far off the edge of the world while keeping us so firmly, and resolutely, attached to the ground beneath our feet.