Making new friends as an adult can be difficult. During a time when almost any social interaction not conducted via webcam was a potential super-spreader event, when most of us were forced to use Zoom to do minimal upkeep on all but our closest relationships, it became nearly impossible. And yet, over the past year or so, my wife and I acquired a new mutual friend: a brilliant, charming, irascible oversharer we call Helen. We spent hours in the company of Helen, laughing or nodding in admiration at the things she does and says, shaking our heads at the romantic and social messes she gets herself into, getting angry at the terrible behavior she endures. (As well as some she is party to—Helen is no saint.)

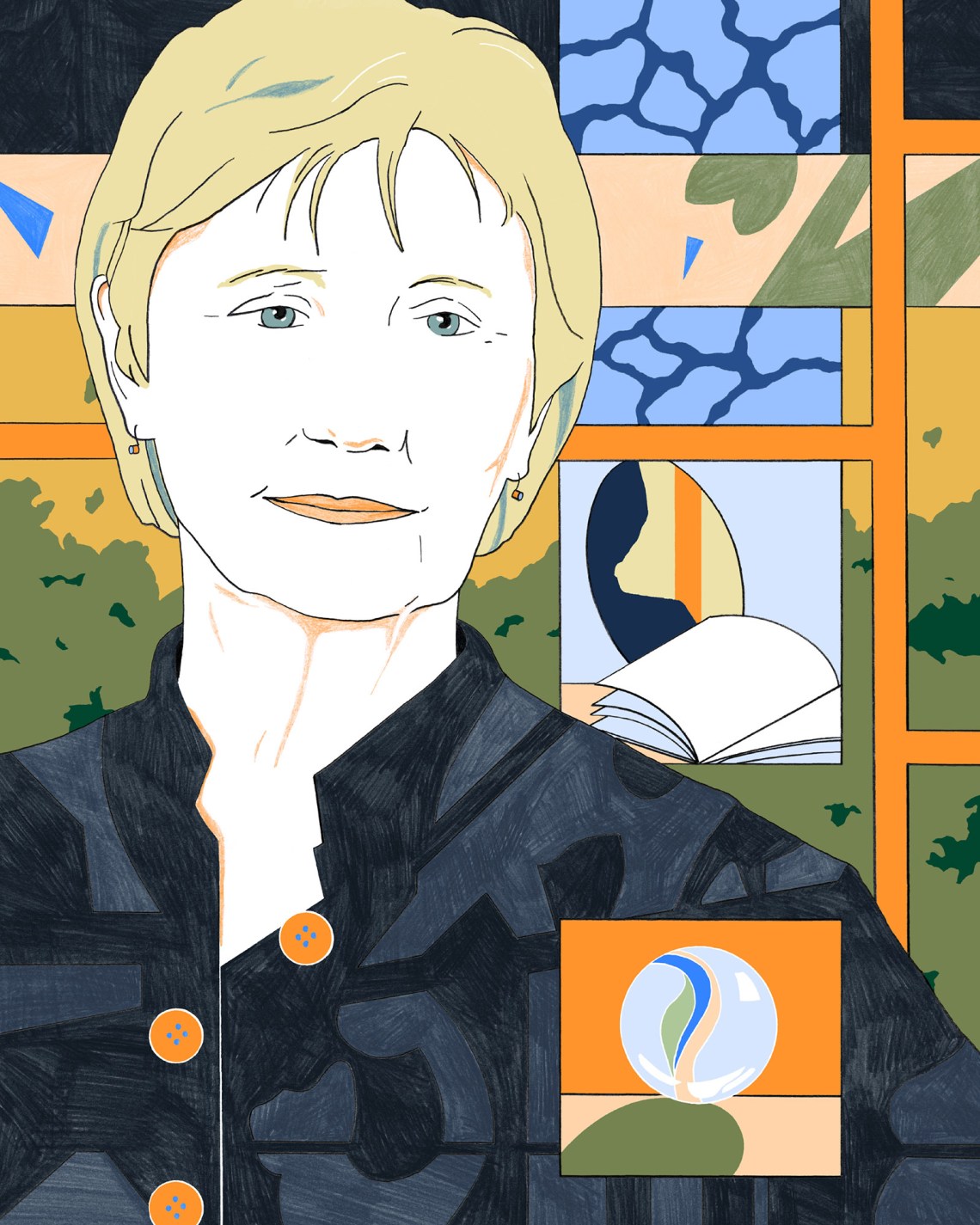

Our Helen is, and isn’t, the renowned Australian author Helen Garner, who, at seventy-nine, is something very close to a literary institution in her country—a fact I’m fairly certain she both cringes at and sees as her due. I can only guess what the real Helen Garner is like, but the one who appears in these two published volumes of her diaries, Yellow Notebook and One Day I’ll Remember This, is a person I’ve come to know intimately.

Helen is loyal and committed as a friend, though somewhat less so as a romantic partner, rarely in a swoon, and often logging evidence for why a relationship is doomed when it has only just begun: “Being in love makes me selfish and mean, puts blinkers on me,” she writes in an entry from 1987. Having spent her young adulthood living in neo-hippie communal households in Melbourne, she is politically progressive and empathetic: when a friend of hers undergoes sex reassignment surgery, she writes, matter-of-factly, that “one is already to use the word she. This is not difficult.”

She does occasionally exhibit impatience with militant identity politics: during a radio interview, the host becomes “almost manic” in her conviction that something Garner wrote has “set feminism back twenty years.” Garner decides to keep quiet and “let the girl pour out her spleen.” But she is just as willing to admit her own failings as a feminist writer: “I’ve been tagging along on men’s coat-tails, watching for their approval, and look where it’s got me.” She considers herself “old-fashioned”—her evidence: “I believe that children should be strictly brought up”—and yet, when she overhears some male academics gossiping about a famous woman who was reported to have had “sixty-four lovers,” she thinks, “You call that a lot?”

Helen is always ready to spill the beans or to judge others witheringly, but she is just as quick to admit when she has no idea what she’s doing. She says exactly what she’s thinking, no matter how bad it makes her or anyone else look. As a journalist friend tells her in 1981, “What’s attractive about you is a very charming…nastiness.”

Helen Garner is underrated outside of Australia, though she enjoys pockets of devoted fandom in the UK and North America, and certainly the publication of her edited diaries is a literary event. These two volumes—a third volume, How to End a Story, was recently published in Australia and will be available elsewhere in 2022—come from Text Publishing in Melbourne, which has been reprinting almost all of Garner’s work, including her original screenplays for the films Two Friends (1986), directed by Jane Campion, and The Last Days of Chez Nous (1992), directed by Gillian Armstrong. (In the latter publication, Garner restored elements that had been cut from the movie because of budgetary constraints, stubbornly reclaiming the script of a film that came out thirty years ago.) Text also recently published gorgeous hardcover collections of Garner’s complete short fiction and essays—Stories (2017) and True Stories (2018), respectively.

Garner’s literary reputation is hydra-headed, resting both on her nonfiction, which tends to focus on true crime and high-profile trials, and her fiction, which is far more domestic in its settings and scenes, and where the only plot-driving crimes tend to be of the interpersonal variety. This split in her oeuvre means that some of her books have devoted readers who might never bother with others. (Perhaps inevitably, her true crime books have sold more, though like most such books, they’ve had a shorter shelf life.) For those who venture on both sides of the divide, however, the differences are mostly superficial. The same curious, funny, mischievous narrative voice animates all of her work. The seeming chasm is a line drawn with chalk.

I first came to Garner through The Spare Room (2008), her masterful, brief, and highly autobiographical novel about a middle-aged woman named Helen helping an eccentric friend through her last months of stage 4 cancer. As the narrator exhausts herself acting as nurse, chauffeur, health advocate, and confidant, growing ever more frustrated with her dying friend’s unwillingness to face the truth about her condition, the novel posits that this exhaustion and frustration is a significant part of how we love others:

Advertisement

Three times that night I tackled the bed: stripped and changed, stripped and changed. This was the part I liked, straightforward tasks of love and order that I could perform with ease. We didn’t bother to put ourselves through hoops of apology and pardon.

The writer who calls out “hoops of apology and pardon” is self-evidently the same one who in This House of Grief (2014)—an award-winning account of the trial, retrial, and ultimate conviction of a man accused of killing his children—dismisses an attempt by the defense to suggest that the defendant could not have committed the heinous act because he loved his kids: “There it was again, the sentimental fantasy of love as a condition of simple benevolence, a tranquil, sunlit region in which we are safe from our own destructive urges.” The people in Garner’s books are defined by their interactions with others; life is communal, even for those who wish it were not so. Her most desolate portraits are of those who get left on their own. (In This House of Grief, she repeatedly expresses pity for the father, despite her growing conviction that he did kill his children, because he seems increasingly lonely and lost in the courtroom.)

In her fiction—a handful of novels and novellas, and few dozen short stories, all of them contemporary, most set in or around Melbourne, where she has spent most of her life—Garner writes about middle- and lower-middle-class women and men for whom the definitions of love and relationship and family are never stable, the rules never set. Mothers, like the one in her 1980 novella Honour, find themselves displaced owing to divorce and the novelty of new living arrangements. Women who never wanted children, like the main character of her 1992 novel Cosmo Cosmolino, end up as den mothers to the damaged drifters who board in their homes. Friends and family members can fall away almost overnight; strangers can swoop in out of nowhere and cause chaos.

There is ample darkness in Garner’s books, even beyond the works of true crime. People die, both literally and spiritually. People are betrayed and abandoned. Parents fail their children at critical moments. Yet the experience of reading her is much warmer and more enjoyable than that description would suggest. Even at its darkest, her world is fundamentally human and empathetic, a place where even infanticide can exist on the spectrum of parental behavior—albeit way out on the edge.

Love is never finished or whole, and neither are her people. “We’ll have to start behaving like adults,” says a character in one of her stories, about a woman having a long-distance affair with a married man. “Any idea how it’s done?” Her characters, real and imagined, are capable of the most awful acts, but are almost never judged for them. More often, she depicts social transgressions with a kind of cheerful acceptance, as in her 1984 novel The Children’s Bach:

Over the back fence, nearer the creek, lived an old couple whom Dexter and Athena had never seen but whom they referred to as Mister and Missus Fuckin’. They drank, they smashed things, they hawked and swore and vomited, they cursed each other to hell and back.

They’re terrible, Garner seems to be saying in moments like these, but at least they’re being honest about how they feel. Honesty—at its most unsparing, risky, noble, and occasionally foolish—is the core of Garner’s work. She has spent her entire career freeing herself from the hoops of apology and pardon.

Garner was born Helen Ford in 1942 in Geelong, a small port city about fifty miles southwest of Melbourne. She changed her last name when she married her first husband, Bill Garner, an actor—with whom she had a daughter, her only child—and hung onto it after their divorce in 1971, and then again through two subsequent marriages and divorces. She has said that “Ford was my child name, and then my really stupid, self-destructive youth name. Garner is my grown-up name.” She had a brief but infamous career as a high school teacher, which came to an end in 1972 after she published an essay describing a pair of impromptu sex education lessons she provided to a group of thirteen-year-old students.

The lesson culminated in a student’s asking Garner if she’d ever performed oral sex on a man. “Yes, I have,” she writes of her reply. “There’s a second of amazed silence…. To break it I say calmly, Well, I guess it is a bit hard for you to picture me with a cock in my mouth.” Though Garner published the essay anonymously, that did not prevent the inevitable. (“Of course they sacked me,” she writes in a 1996 postscript.) In A Writing Life, a 2017 biographical study of Garner’s work, Bernadette Brennan adds a delectable detail to this incident: “She met with the school principal, was shown his draft report to the Department of Education and, in typical Garner manner, corrected his spelling.”

Advertisement

The story of Garner’s firing establishes early the themes of her career: a forthright and cheerful willingness to explore seemingly untouchable subjects, as well as a habit of walking blindly into trouble, driven partly by ruthless honesty, partly by naiveté, and partly out of an unmistakable sense of mischief. (The recent decision to publish volumes of her private diaries while she—along with many of the people she writes about in them—is still very much alive and active is clearly born of the same tendencies.)

Finding herself with unexpected free time after losing the teaching job, Garner started going through the diaries she’d been keeping, with an eye to possibly drawing a book out of them. She describes this pivotal moment in a 1996 essay called “The Art of the Dumb Question”:

At first you simply transcribe. Then you cut out the boring bits and try to make leaps and leave gaps. Then you start to trim and sharpen the dialogue. Soon you find you are enjoying yourself…. What is it, though? Have you got the gall to call it a novel?

She did, as it turns out. As she puts it in the same essay, “A year later, Monkey Grip was in the shops.”

Monkey Grip, her first novel, published in 1977, is a loosely structured yet intense account of a young single mom named Nora sliding through a series of late-era hippie communal homes in Melbourne, in love with an intermittently charming heroin addict. It was a best seller and brought Garner near-instant literary fame and notoriety in Australia, where it is considered a modern classic and is a touchstone for many contemporary feminist writers. It is also the rare “counterculture novel” that still feels immediate and alive, thanks to Garner’s sharp, precise prose—she has spoken of her desire to keep the shape and speed of her prose as close to speech as possible—and her preternaturally wide empathy. We are drawn into Nora’s doomed infatuation as easily as we might that of an Austen heroine or a member of Miss Jean Brodie’s set, never having to adjust for the book’s era:

I went out all day and didn’t see him till six-thirty in the evening, when I found him in the theatre. His pupils were large. He did not seem pleased to see me, and was offhand and cold. I went home and did four loads of washing at the laundromat. I washed his shirts and jeans and socks. Why do I do it? I do it for love, or kindness. Women are nicer than men. Kinder, more open, less suspicious, more eager to love.

Some of Monkey Grip’s early reviewers trashed Garner for hewing too closely to her own life, for assuming, as one (male) critic put it, “that the reader will share the author’s absolute fascination with herself.” Garner admitted in a 2002 essay to going “round for years after that in a lather of defensiveness,” insisting that Monkey Grip is “a novel, thank you very much,” but also that she is “too old to bother with that crap any more. I might as well come clean. I did publish my diary. That’s exactly what I did.”

In the mid-1990s Garner consummated a growing obsession with trials and court proceedings by swerving away from fiction and into true crime. Her first book in the genre, The First Stone (1995), a best seller, made her a cultural and political target by seeming to take the side of a middle-aged male college official accused of being inappropriately handsy with two young female students at a party. (In an essay on the book and its attendant controversy, Garner accused her critics of “being permanently primed for battle” and “read[ing] like tanks,” which probably didn’t help.)

The feminist anger at Garner eventually cooled, but the critical perception of her as a raging literary narcissist, stuffing each book to the margins with herself, has persisted. Even The Spare Room and This House of Grief, minor masterpieces in their respective genres, were hit with the charge of containing Too Much Helen.

I’ve never fully understood the tendency of some readers and critics to view the interplay between an author’s work and the facts of her life as a matter of ethics or integrity, as if there were something morally greasy about drawing too heavily on autobiography in the creation of art. Anytime a literary writer is accused of narcissism, I have the same response as when I hear a US president called a war criminal: well, duh. It must be a question of degree. All of Garner’s work, in every genre, is open, playful, and spacious; we don’t get smothered by her authorial self in the way the British publisher Carmen Callil described the effect of reading Philip Roth: “It’s as though he’s sitting on your face and you can’t breathe.”

Also, does the truth really matter once it’s been transformed into fiction? Most writers’ biographies are only useful for literary gossip and choice anecdotes. Even the best of them are rife with confident assertions as to which parts of an author’s life correspond with which elements of their work. (An Alice Munro biography from 2005 has the irritatingly presumptuous title Writing Her Lives.) Even if you could be 100 percent certain about a particular life-to-fiction connection, what would you be left with? It’s like identifying a street corner where a scene from a famous film was shot—there may be a small thrill of recognition, but it doesn’t tell you much about the film itself. As Martin Amis once put it, the ideal reader “regards a writer’s life as just an interesting extra.”

Garner herself writes about the dissociative process of inspiration in an entry from One Day I’ll Remember This: “It’s as if I’ve extracted or borrowed from the real person the aspects of them that I needed to struggle with, and the character consists only of those aspects. I can return to the real person with no sense of overlap.”

The criticism that Garner puts too much of herself in her work also misses a large part of what makes her books so good: their unnerving sense of immediacy. In the essay “Woman in a Green Mantle,” Garner mentions Philip Larkin’s belief “that the urge to preserve is the basis of all art,” adding that she has “had it up to here with rhetoric about art; but the urge to preserve—I understand that. I’ve been a captive of it for most of my adult life.”

What matters is what she chooses to preserve, which is not, as in the work of so many other autobiographical writers, her early wounds and worries, or the sights, sounds, and smells of her childhood homes, but rather her life as it is now. She keeps her experiences alive by transforming them into living art, not by placing them under glass. “That’s why I write the way I write, so that people can go there,” Garner has said. “When you open a book, you’re throwing yourself into the arms of a writer. It should say, ‘I’m here! Come in!’” In One Day I’ll Remember This she records an exchange with her third husband about Australia’s history: “I’ve got no feeling for the past,” she tells him, to which he replies, very perceptively, “You’ve got a pretty strong sense of the present, though, haven’t you.”

A strong sense of the present is the central paradox of Garner’s published diaries. The occasional reminders of the provenance of some of the entries—when, for example, she expresses wonder over a fax machine or notes the protests in Tiananmen Square—feel almost like editorial insertions, as when characters in a period movie overhear a historically significant piece of news on the radio. Early on in Yellow Notebook, she writes that “a reviewer of a collection of women’s diaries from the late eighteenth century is surprised to find that they’re about family affairs and do not mention the French Revolution. I don’t find this at all surprising.” Garner is concerned with capturing not a moment in time but her own perception of that moment, her feelings as a person living through it—or, more accurately, stumbling through it. Which means that, as with her fiction, there is no datedness here: even the entries written forty years ago feel as though they could have been written last week.

In a sense, Garner’s diaries are the culmination of her lifelong blurring of the lines between fiction and nonfiction. “I need to devise a form that is flexible and open enough to contain all my details, all my small things,” she writes in an entry from 1989. “If only I could blow out realism while at the same time sinking deeply into what is most real.” It’s hard not to feel that Garner is giving us a knowing look here, since the volumes we are reading appear to be the solution to the very problem she is describing. As Joan Didion once wrote, “Our notebooks give us away, for however dutifully we record what we see around us, the common denominator of all we see is always, transparently, shamelessly, the implacable ‘I.’”

These diaries begin shortly after the publication of Monkey Grip, in part because Garner burned all of her earlier notebooks decades ago: she has described herself as being “so bored with my younger self and her droning sentimental concerns that there was nothing for it—this shit had to go.” (The act of burning the earlier notebooks is, of course, dutifully noted in the later diaries, in an entry from 1994.) Garner edited her diaries, selecting the entries, and though she doesn’t say how much she cut, she claims to have made only the most minor changes to what she left in. “I could trim, I could fillet, yes, but I was not to rewrite,” she has said about the process.

To select, fillet, or trim is, of course, to get a large part of the way toward creating, so it’s no surprise that the Helen of the diaries is a semi-fictional construct, a character in every sense of the word, one who exists at the nexus of art and autobiography. Helen is a sharp critic: reviewing a collection of short fiction, she notes that “the only woman in it is the naked one on the cover.” She is unsnobbishly catholic in her tastes, noting her “rave review of Wayne’s World” but also that she was “swept away” at a production of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Reading interviews from The Paris Review, she gets annoyed by authorial egotism—“Nabokov: too clever and nasty. Kerouac: vain and noisy, a show-off. Eudora Welty: a nice, dear old lady full of respect and modesty”—and disparages the idea of taking her accomplishments too seriously.

But she is honest about her petty desires, as when her second novel is shortlisted for a major award: “I don’t know who I’m up against but I want that prize.” Repeatedly, despite her success as a writer, she questions her status:

I’m worried about art, what it’s for, whether what I do is any use to anyone, whether I’ve been kidding myself all these years that I’m any good at it, that I’ve got anything at all to offer the human race, whether I should just chuck it in and look for a job.

Obviously, making an imaginary friend out of the version of herself an author presents in her own diaries is probably not the appropriate response for any critic who has been trained to respect the treacherous gulf that lies between text and creator—who has, in other words, read some Barthes. But it demonstrates how seductively Garner creates her diaristic world, allowing readers to enter her life—that “interesting extra”—in ways that make it difficult to maintain a proper critical distance. Reading the published diaries of, say, Virginia Woolf, we are constantly aware that we are in the presence of genius, of someone whose literary sensibilities and powers of perception are far beyond ours. Woolf’s diaries are full of self-doubt, pettiness, and worry, but those passages feel like the momentary lapses of a god or a parent, or at least an indisputably brilliant older sibling. We must work to be worthy receivers of her private musings.

Reading Garner’s diaries, we encounter someone much more human, quick-tempered, and messy. Over the course of the books, we get drawn into her struggles—with men, with work, with age, with burgeoning religious urges, with her critical reputation—and before we know it, we start responding, assuring her that whatever book she’s working on will be great, and not just because we, to borrow an idea from the comedian Mike Birbiglia, are in the future. We commiserate with her over professional slights (like when she is mistaken “by three separate male writers for a staff helper” while attending a literary festival in Toronto) and bite our tongues when she fills us in on her latest love affair—or affairs: Yellow Notebook ends with Helen in the midst of relationships with not one but two married men. In One Day I’ll Remember This, we watch, helpless, as she marries one of those men, who, as “V,” gradually becomes the closest thing the book has to a villain. (Most of the people who appear in the diaries are given an initial as a pseudonym, but it’s fairly easy—with the help of Bernadette Brennan’s book and Wikipedia—to work out who the central people are.)

Garner’s diaries will not be much use to future cultural historians; they exist for readers right now, at a moment when their author is alive and willing to own up to what seems, on the surface, to be an impressive act of self-indulgence, but somehow feels like a generous gift. As with the best literary diaries, there is much here that is witty and wise and quotable, but the heart of these volumes are the moments when our new friend acts out in sudden, emotional, and downright silly ways. In an entry from 1990, Garner notes that she is reading an essay in which Woolf is quoted as haughtily dismissing Robert Louis Stevenson’s use of adjectives, of all things: “Ooh I was furious! She’s a goddess, but at that moment I wanted to kick her flabby Bloomsbury arse.”