The great Rosa Luxemburg, radical extraordinaire, possessed a rich appreciation of life in all its glorious variety. While the potential for socialist revolution was her passion, she was sensually engaged by love and literature, flowers and music, sunlight and philosophy. She had, as well, an ardent interest in replacing the theory-driven jargon that dominated the speech and writing of her fellow socialists with the lucid plain-speak that could stir the hearts as well as the minds of the rank and file. She wanted working men and women to feel the beauty of Marxism as she felt it.

Luxemburg also loved a man who was her polar opposite: Leo Jogiches, a rigid Marxist whose temperament was as angry, brooding, and remote as Rosa’s was warm, open, and immediate. Jogiches subscribed wholly to the credo of the Russian radical Mikhail Bakunin, which famously declared:

The revolutionary is a lost man; he has no interests of his own, no cause of his own, no feelings, no habits, no belongings; he does not even have a name. Everything in him is absorbed by a single, exclusive interest, a single passion—the revolution.

This made Rosa crazy. As she and Leo hardly ever lived in the same town at the same time, their correspondence was vast, and on Rosa’s end often despairing. She once wrote him, “When I open your letters and see six sheets covered with debates about the Polish Socialist party and not a single word about…ordinary life, I feel faint.”

Tess Slesinger is the prodigiously talented, left-leaning writer of the 1930s whose fiction was often grounded in social realism but also in a modernist irony that Luxemburg might well have envied, as the situation that Slesinger repeatedly nailed would have been most gratifying to her: a marriage wherein the wife tries to convince the husband that personal happiness and the struggle for social justice need not, indeed must not, be mutually exclusive. Implicit in this view is the belief that if people give up sex and art while making the revolution, they will produce a world more heartless than the one they are setting out to replace.

Tess Slesinger was born in 1905 in New York City into a well-to-do Jewish family of European extraction. She was educated at the Ethical Culture School in Manhattan, then Swarthmore College and the Columbia School of Journalism. In 1928 she married Herbert Solow, an intellectually rigorous man on the left associated with the Menorah Journal, a leading Jewish-American magazine of the 1920s and 1930s, among whose editors and contributors could be counted Elliot Cohen, who, years later, became the first editor of Commentary, and Lionel Trilling, who, years later, became, well, Lionel Trilling.

Around these people swirled a group of marvelously neurotic literary and political intellectuals devoted to the idea if not the reality of socialist revolution. It was among them that Slesinger experienced the kind of sensory deprivation that encouraged her gift for criticizing intellectualism bereft of emotional intelligence.

In 1932 Slesinger divorced Solow and made her way to Hollywood, where she embarked on a remarkably successful career as a screenwriter. Here, on a movie set, she met a producer and screenwriter named Frank Davis who, in 1936, became her second husband. With Davis she had two children and teamed up to write the screenplay for a number of films, among them A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. In 1945 her life was cut short by cancer. She was just thirty-nine years old but she’d lived long enough to leave behind a small, memorable body of work—the 1934 novel The Unpossessed, in which the left-wing intellectuals Slesinger had known were gathered and skewered, and a collection of stories, Time: The Present, published in 1935.

In 1971 the book of stories was republished under the title On Being Told That Her Second Husband Has Taken His First Lover. Now it is again being reprinted, this time under its original title, and the collection is composed of tales taken from the first book with some new ones added, all I believe published in her lifetime, all distinctively Tess Slesinger. There is the parody of clockwork efficiency practiced in a shabby department store during the Depression (“Jobs in the Sky”). There is the socialite in “After the Party” who’s had a nervous breakdown because her wealthy husband had gone out of his mind and left a sizable portion of his fortune to…the Communist Party! There is the fragmented confusion that overtakes a man in a highly secure position when he is unexpectedly fired (“Ben Grader Makes a Call”). And there is the daring fragment called “The Lonelier Eve,” an evocative vision of the mental extremities to which those anomic times had led.

Slesinger’s work has almost always been written about by men on the left who think it belongs on their library shelves. This, I believe, has done Slesinger a grave disservice, as the social and political background of her work is just that: background. The central meaning of Time: The Present resides in the stories that illustrate the shocking strangeness of sexual intimacy, especially among people for whom marriage has been a rude awakening. It is here, with this subject, and mainly through her repeated use of the internal monologue—often brilliantly original—that Slesinger’s mind shines and her talent reaches far.

Advertisement

In the story “On Being Told That Her Second Husband Has Taken His First Lover,” we have a woman talking to herself as she lies in bed in the arms of her husband, who has just confessed to an infidelity and is anxious to know that he will be forgiven. He obviously thinks this is the first she will have even imagined his cheating on her, but she has in fact long suspected it. “So it’s nice my dear,” she is saying to herself,

that you are always so clever; and sad my dear that you always need to be. Time was when a thing like this was a shock that fell heavily in the pit of your stomach and gave you indigestion all at once. But you can only feel a thing like this in its entirety the first time.

The narrator sees the fear in her husband’s face and she despises him for it, while being gripped by her own fear that he might leave her. Then the ineluctability of the situation hits her full force: “For you see it all suddenly, you see it there in his face, reluctant as he is to hurt you”—he is not going to end the affair. In fact:

He will be lost to you the minute he walks out of your sight; he will be back, of course, but this time and forever after you will know that he has been away, clean away, on his own. You see it in his face, and your heart, which had sunk to the lowest bottom, suddenly sinks lower.

To this day these lines cast a chill.

Of course not a word of these thoughts is ever spoken out loud. In the course of this monologue we come to feel viscerally the treacherous undertow that pulls at a marriage in which the burden of disastrously mixed feelings conspires with what is said and what is not said to make each partner ultimately feel trapped in an alliance with a stranger posing as an intimate.

In one version or another, this same wife and husband appear in the stories “Mother to Dinner,” “For Better, for Worse,” and “Missis Flinders.” In all of them a woman, young or initiated, puzzles over the inescapable feeling that, essentially, the man she calls her husband is “other.” He is the man to whom she is married, yes. The man with whom she lies down every night, yes. The man whose disapproval makes her heart shrivel, yes. But what does all that mean? Who, after all, is he? She will never have the answers to these questions, but marriage is the school she attends in order to learn who she is.

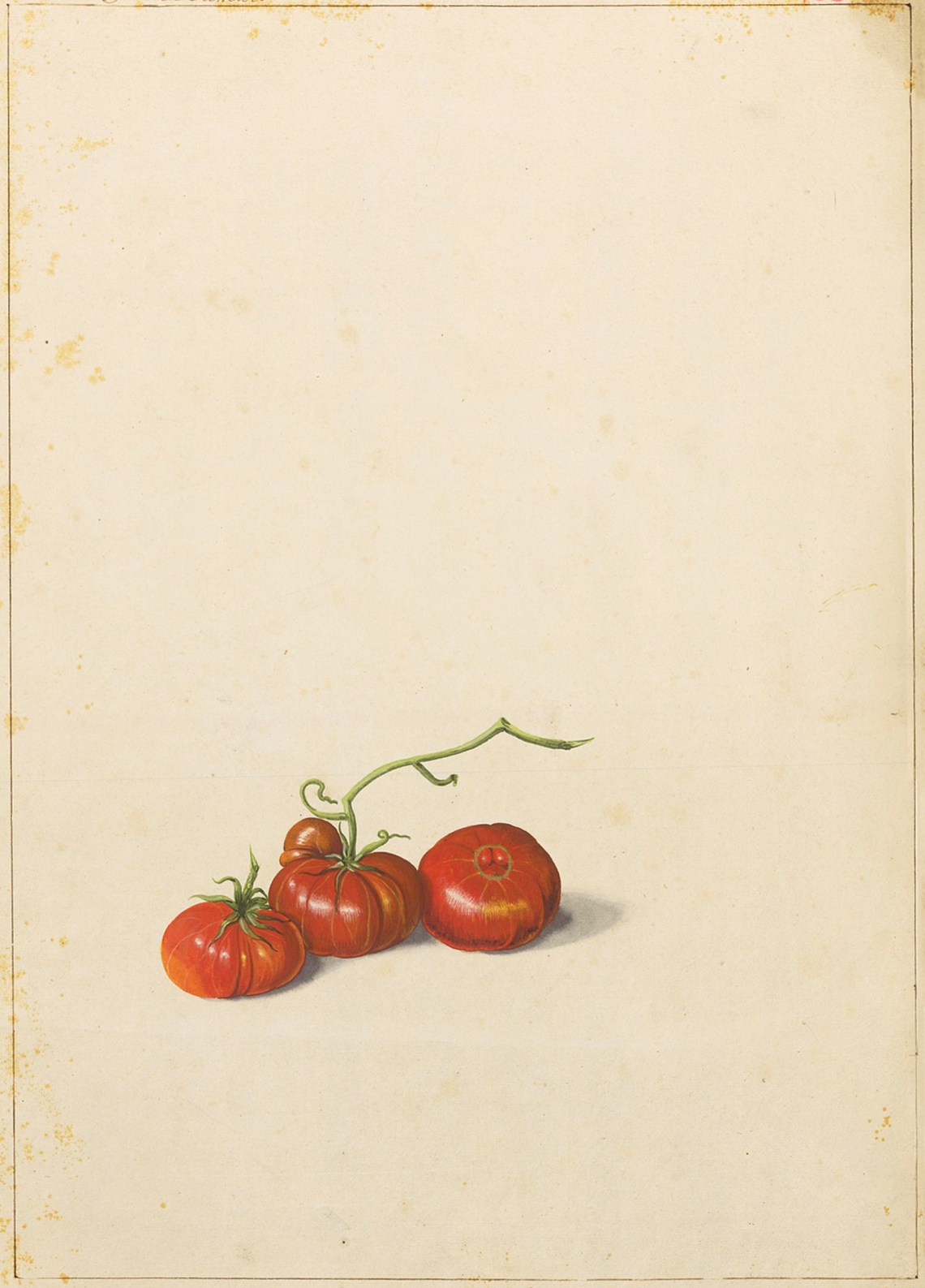

In “Mother to Dinner” we are invited into the mind of Katherine, a twenty-two-year-old bride of eleven months who has been out shopping for a dinner she plans to make that evening for her husband and her parents. While shopping, Katherine has been delighted to watch herself imitating her mother’s life—the pleasure she’s taken in choosing this cut of meat, that firm tomato. However, the scorn of Katherine’s husband, Gerald, a man of severe intellectual standards who holds her bourgeois mother in contempt, keeps breaking into her daydream. She recalls his often having taunted her with the prediction that because she had no serious work, and thinks so much of little things (like shopping for dinner), it would not be long before she became her mother. Would that really be so bad? Katherine thinks resentfully. As she walks home, she feels herself already frowning across the table at her keenly intelligent husband “politely insulting” her clueless mother.

More than frowning—agonizing over his anticipated behavior. She thinks of all the women she’d seen shopping and wonders if they’re aware of “the uprooting, the transplanting, the bleeding, involved in their calmly leaving their homes to go to live with strangers.” Suddenly, she is attacked by loneliness and feels a strong desire to call her husband, but she knows she’ll only get his firm, businesslike voice asking, “What do you want, dear?” And that stops her cold: “Probably Gerald was right, she thought wearily—for he was so often ‘right’ in a logical, meaningless way”—when he said that thinking, as she did, about every small thing was “an imbecilic waste of time,” an irrelevance. Yet she can’t help also thinking, “Between two people who lived together, why should anything be irrelevant?”

Advertisement

On the other hand—and she has no reason to not want there to be another hand—she’s been shocked to realize that she herself has something to answer for. If she’s honest with herself, she must admit that as much as she loves and admires Gerald, she had expected to regard him as her mother regarded her father—“with a maternal tolerance touched by affectionate irony”—and this had put him on his guard. He was right when he said to her, “You resent me because you have a preconceived idea of the rôle to which all husbands are relegated by their wives; you’d like to laugh me out of any important existence.”

This last sentence is the key to many Slesinger stories in which we have a husband bent on devoting himself to large, world-making concerns while his wife wishes to “trap” him in the insignificance of domestic happiness. Interestingly, when Slesinger allows the husband to speak for himself, his position is not without merit. While the dominating point of view belongs to the woman, it often seems that Slesinger wishes to mete out some measure of sympathy to the man as well; laying blame on him is not really what she’s up to. Even in “Missis Flinders,” the most savage and the most woman-centered of the internal monologues, a ragged vein of pity for both the wife and the husband runs just beneath the story line.

“Missis Flinders” was first published in 1932 in Story magazine and made a tremendous stir because it openly used abortion as the issue at stake in a marriage that is failing for the reason most marriages fail: emotional goodwill, if it ever existed between this husband and this wife, is now draining slowly away.

Margaret Flinders, one half of a radically left couple, stands on the steps of a maternity hospital watching her husband, Miles, running about in the street, trying frantically to hail a taxi so they can get home to face the alienating consequences of the decision they’d taken to abort the child she had been carrying. Margaret had wanted this baby badly but Miles persuaded her that nothing was more important than ensuring their economic (and therefore intellectual) freedom. “We’d go soft,” he had said, if they started having children. “We’d go bourgeois.”

Yes, she repeats to herself, with the taste of iron in her mouth, they’d go soft, “they might slump and start liking people, they might weaken and forgive stupidity, they might yawn and forget to hate.” Having a baby meant

the end of independent thought and the turning of everything into a scheme for making money;…why in a time like this…to have a baby would be suicide—goodbye to our plans, goodbye to our working out schemes for each other and the world—our courage would die, our hopes concentrate on the sordid business of keeping three people alive, one of whom would be a burden and an expense for twenty years….

She had begun to see Miles as “a dried-up intellectual husk; he was sterile; empty and hollow,” as she herself now feels, driven to mask his personal anxieties behind the political rhetoric of their times. And then comes an implicating thought. Perhaps it was really that one needed to believe in oneself in order to welcome parenthood—and neither she nor Miles did. Perhaps, after all, parenthood meant having the courage to risk seeing oneself replicated in another human being—and neither of them did. After which comes an even greater suspicion: “Afraid to perpetuate themselves, were they? Afraid of anything that might loom so large in their personal lives? Afraid, maybe, of a personal life?”

Within two years of its original publication “Missis Flinders” became the final chapter of Slesinger’s novel, The Unpossessed, which featured Margaret and Miles as leading figures in a small cast of characters modeled on a number of people in the circle around her first husband. Besides the Flinders themselves there is Jeffrey Blake, a compulsively womanizing novelist; Jeffrey’s blindly adoring wife, Norah; Bruno Leonard, an intellectually brilliant but emotionally compromised drunk (“He longed like a dead man for sensation, envying in Jeffrey a purity of desire that he knew could never be his own”); and Bruno’s despairingly promiscuous cousin, Elizabeth. These people are left-wing intellectuals one and all who, in the course of the novel, gather together on various occasions for the sake of creating a magazine that will shock its readers into experiencing viscerally the rapacity of the capitalist world. Ultimately, their myriad insecurities lead them into a quarrelsome inertness that prevents the magazine from ever getting off the ground. At novel’s end, the reader is left with an overpowering sense of the inescapability of human self-defeat.

Many on the left have deplored The Unpossessed for what was said to be Slesinger’s unknowing presentation of the politics undergirding its story. When the book was published the political philosopher Sidney Hook supposedly said that Slesinger never understood a word of the arguments swirling all about her at the Menorah Journal. Then, in 1966, Lionel Trilling, who had liked it quite a bit, wrote in his essay “Young in the Thirties” that the book would have been much better had there been more political analysis in it. And in 2006 the late literary critic Morris Dickstein wrote an admonishing review, also on the basis of the novel’s political shallowness. Dickstein’s review especially surprised me, as it was hard to see how at this late date the book could still be criticized on those old grounds when, for this reviewer at least, it seems perfectly clear that the real meaning in The Unpossessed resides in the relationship between Miles and Margaret Flinders, while the politics is the metaphorical context within which it unravels. The opening scenes of the novel set the stage for all that is to come.

Margaret is shopping for dinner—a circumstance Slesinger made use of more than once—and we are privy to her thoughts as she gathers her bundles of food together and starts walking home, musing on where her life is going. Is there any forward motion to be reported on? Well, there’s her job as secretary to the boss at a technical magazine called Business Manager. Last year, she mocks herself, the boss had signed his own letters, this year she signed them, and that was progress, wasn’t it? Then, since she considers herself a person of the left she must have a worried thought about the world situation (“Last year it seemed that the Scottsboro boys must hang without much ado”) and, after that, one about the inner mood of her seriously leftist husband (“Last year Miles’ soul was worn about the edges but displayed no gentle fraying in the seams”). Then, almost as an afterthought, “Twenty-nine! what was the deadline for babies? for clearing out and starting somewhere else?”

What comes next provides a shock but not a surprise. Back at her building, Margaret sees that her windows are lit up, knows that Miles is home, and suddenly she seizes up: “O drop the bundles on the nearest stoop; turn round and run, run back, run the wrong way…run and chase the world that hides around the corner!” Almost immediately, after these subversive thoughts, comes a frightened turnabout:

She raced up the stairs in terror, in doubt.

She burst the door open—and in the pit of her being peace vanquished regret…for he sat there with his feet on a chair and with all that she loved and all that she hated him for written plainly on his face; he had come home, like a child, for his supper. He took off his glasses and his eyes opened and closed several times patiently like a baby’s growing used to her light. And she herself was taking off her hat to stay (enormously bored, enormously relieved) at the same moment that she advanced to kiss him….

She would pierce his wavering smoke-screen and purge him with her comfort.

Thus ends chapter 1. And thus begins chapter 2:

But comfort was salt to his wounds…. All of his life women (his aunts, his frightened mother, now Margaret) had come to him stupidly offering comfort, offering love; handing him sticks of candy when his soul demanded God; and all of his life he had staved them off, put them off, despising their credulity, their single-mindedness, their unreasoning belief that on their bosoms lay peace. For if he were once to give in, to let their softness stop his ears, still the voices that plagued him this way and that, they would be giving him not peace, but death; the living death of the man who has consented to live the woman’s life and turned for oblivion to love as he might have turned to drink.

So there we have it: social realism laced through with the psychological insights of modern times. Locked as Miles and Margaret are into a set of clichéd fears that equate women with the sentimental fantasy of personal fulfillment and men with the equally sentimental fantasy of saving the world, the politics that grounds The Unpossessed becomes a skeleton upon which is hung the flesh of this consequential divide. For him she is the end of all hope of transcendence, for her he is the repression that stops emotional maturity in its tracks. Ah, Rosa! Ah, Leo!

Slesinger was often compared to Mary McCarthy, a writer who was also given to lavish bouts of irony and irreverence. But McCarthy’s irony always carried the sting of one who takes no prisoners, whereas Slesinger, no matter how taunting, leaves her readers feeling that courage and cowardice in her characters are dealt out indiscriminately. The deeper story in Slesinger is always that of people trapped together in levels of anxiety that approach dread. For this reason her mockery stops short of character assassination, and her feeling for life’s unavoidable sorrow remains haunting. Together, Time: The Present and The Unpossessed strike a chord of human watchfulness that more often than not gives up the satiric for the tragic.

This Issue

February 10, 2022

Our Lady of Deadpan

Picasso’s Obsessions

In the Beforemath