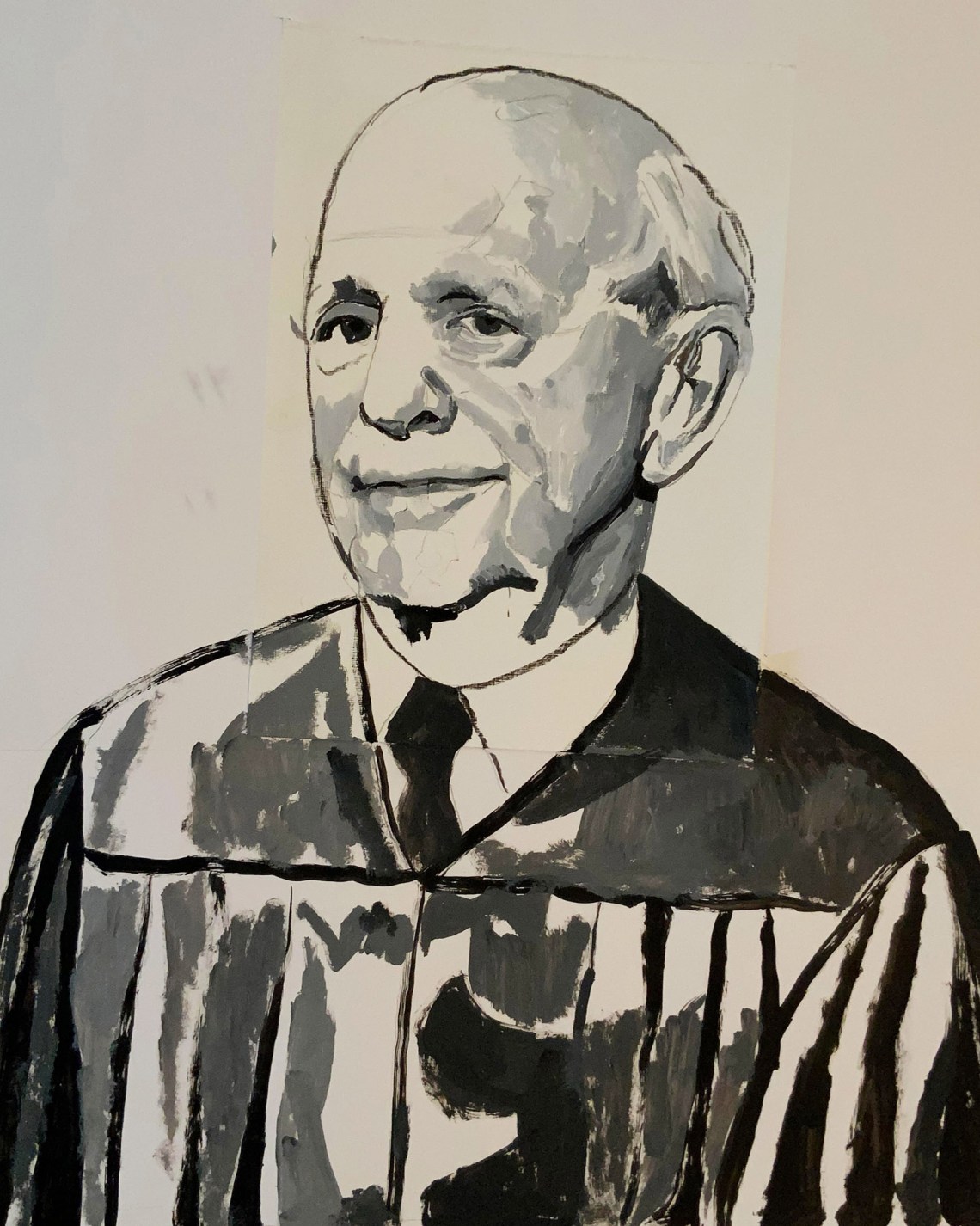

From Plato’s Republic to Ibsen’s The Wild Duck, from Pascal’s Pensées to Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, writers have pondered the Noble Lie—the morality of resorting to falsehood and delusion to conceal, usually from the masses but sometimes from oneself, truths whose revelation would wreak havoc, or at least do more harm than good. It is a question that Justice Stephen Breyer, the dean of the Supreme Court’s liberal wing and its fiercest proponent of the Enlightenment values of truth and reason, might have taken up in his latest book, The Authority of the Court and the Peril of Politics, published a few months before his recent announcement that he intends to retire from the Court.

After all, the book’s implicit theme is that the Court—and by extension our republic and the rule of law, which depend, he argues, on the Court retaining its current influence—would be threatened if fears that it has become too politicized were voiced out loud. He could have grappled with the idea that protecting the Court from a loss of public trust might require purveying the Noble Lie that its decisions are, despite all appearances, truly apolitical in character, and that all nine of its justices can be trusted to abide by the oath they take to “support and defend the Constitution of the United States” and to “administer justice without respect to persons, and do equal right to the poor and to the rich.”

Unfortunately Breyer’s book, surely the least impressive of his considerable body of extrajudicial writings,1 is not a thoughtful exploration of the virtues and vices of well-meaning deception.2 In his stubborn avowal that the Court—even with its current far-right supermajority—remains an apolitical body, he perpetuates a lie that is anything but noble. I have written much that is entirely positive about his judicial opinions,3 so it pains me to say that his book reads as though it had been written by someone oddly unaware of the implausibility of its factual claims.

Invoking Cicero, Breyer opens by noting that legal obedience, the kind a society needs if it is not to descend into chaos and what Tennyson called the law of “tooth and claw,” requires either fear of punishment, hope of reward, or belief that the law is just even when it doesn’t deliver what you hope for. The central thesis of his book is that the reason Americans have over time abided by the Supreme Court’s interpretations of the law, even when disagreeing with them—he emphasizes that he himself has written any number of dissenting opinions—is that they have accepted the view that the justices are not acting “politically.” By “politically,” he seems to mean in accord with the positions of the political party to which they or the president who appointed them belongs. But from Breyer, a former Harvard Law School professor with nearly three decades of experience on the nation’s highest court and with a well-deserved legacy as its leading pragmatist, one hoped for something more nuanced if not more genuinely original.

Instead, Breyer’s own accounts of the most famous episodes in the Court’s history appear to undercut his thesis about the source of its power. Writing about Brown v. Board of Education (1954), for instance, he recalls that that monumental ruling was met not with compliance by those who disagreed with it but with outright defiance. President Eisenhower had to deploy the 101st Airborne Division to integrate Central High School in Arkansas over the opposition of Governor Orval Faubus and the state police.

Breyer recounts a conversation he had with the late civil rights leader Vernon Jordan in which he asked whether Jordan thought “the Court had actually played a major role in ending segregation” given that, “even absent the Court…there [would] have been enormous pressure to end that system—pressure from civil rights leaders, from the rest of the country, indeed from the entire world.” Jordan “answered that of course the Court had been critically important” in “at the very least…provid[ing] a catalyst,” thereby winning “a major victory for constitutional law, for equality, and above all for justice itself.” That’s exactly the story that constitutional law teachers have been telling their students about the Supreme Court for generations. I am no exception.

Much serious scholarship, none of which Breyer calls to the reader’s attention, tells a far less idealistic tale about the power of the Court.4 But even if that rosy version were largely accurate, it leaves open the question of whether the success of Brown, such as it was, actually depended on persuading people that the Court’s decisions in that and other controversial cases were not basically expressions of political and moral views filtered through legal categories and conveyed in a legal voice. Did the public’s appreciation for what Breyer depicts as the strictly “legal” (as opposed to “political”) character of the unanimous ruling in Brown significantly help “to promote respect for the Court” and increase “its authority”? His answer is yes: “I cannot prove this assertion. But I fervently believe it.” If we are looking for something more than one seasoned judge’s hunch, we won’t find it in Breyer’s book.

Advertisement

The same must be said of every other story he tells, including most prominently that of Bush v. Gore. There were vociferous nationwide protests against the Supreme Court’s 5–4 decision to halt the Florida recount in the 2000 presidential election and effectively make Governor George W. Bush of Texas the next president, even though, at the time, he led Vice President Al Gore by only 537 votes out of nearly six million cast in Florida—in a nationwide election in which Gore was over half a million votes ahead of him.

Nor were those protests utterly without legal merit, as a mountain of academic writing in the two decades since that decision attests.5 In Breyer’s account, the reason the nation accepted the outcome without bloodshed was the accumulated respect for the Court as an impartial, apolitical arbiter of the most contentious questions, an attitude “so normal that hardly anyone notices it,” much like “the air around us, also unnoticed,” that “allows us to breathe.”

Most of us would accept the far simpler explanation that after the protracted legal wrangling and ballot recounts that took place between the election on November 7 and the Court’s decision on December 12, people had become exhausted and were prepared to accept certainty over continued vote-counting in an election in which every recount of millions of paper ballots with their infamous “hanging chads” was likely to make physical changes in some of the ballots themselves—an all but impossible situation in which the margin of error in each recount probably exceeded the margin of victory.

Nonetheless, Breyer prefers to assert, without evidence, that acceptance of that decision is another corroboration of his thesis that the Court’s capacity to secure popular obedience and preserve the rule of law is a result of belief in the apolitical character of its decisions, even in the most politically charged cases. He says nothing to explain the counterexamples, like the Court’s decisions in the 1960s banning mandated prayers in public schools, which were all but ignored in many parts of the country despite the force of the legal reasoning underlying them and the fact that President Eisenhower—a Republican—had appointed three of the six justices who made up the majority in the most important of them, Engel v. Vitale (1962).

Breyer’s dubious defense of his claim that the Court’s judgments are fundamentally apolitical and need to be perceived as such in order to be accepted by the public is flawed in other respects as well. He barely scratches the surface when considering whether the methods of legal interpretation increasingly used by different groups of justices are likely to produce conservative or liberal outcomes in particular cases. Breyer cannot deny that the insistence on interpreting constitutional provisions—about such matters as liberty, due process of law, equal protection of the laws, unreasonable searches and seizures, or the right to bear arms—in accord with their “original meaning” emerged as a major theme in Supreme Court decisions with the growing influence of conservative justices appointed by Republican presidents, such as Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, or the three appointed by President Trump, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett.

Nor can he deny that an emphasis on the evolving meaning of constitutional guarantees and a willingness to weigh the social consequences of competing constitutional interpretations are more typical of justices like himself and his two liberal colleagues on the current Court, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan. He seemingly cannot deny that the partisan splits within the Court on matters like abortion, voting rights, criminal justice, and business regulation reflect distinct political ideologies couched as methodological differences. And yet he is content to express his belief that “jurisprudential differences, not political ones, account for most, perhaps almost all, of judicial disagreements”—even while conceding that “it is sometimes difficult to separate what counts as a jurisprudential view from what counts as political philosophy, which, in turn, can shape views of policy.”

What accounts for these so-called jurisprudential differences? To what degree are they mere window dressing, attached after the fact to conclusions consciously or unconsciously reached on other grounds? And even if these differences are genuine, mustn’t we explore the extent to which they are politically and morally neutral? After all, we’re talking about different worldviews, different perspectives on the nature of legal institutions and the purpose of law in people’s lives.

Advertisement

In part, what’s at stake is the difference between believing that social and cultural change tends naturally toward deterioration and division and thus is best held at bay with rigid legal rules, and believing that such decay is the result of rules that fail to evolve. When a growing body of serious scholarship supports the view that those different beliefs are more likely today than in times past to map onto demographic and/or partisan differences,6 it’s simply not enough to note with charming, almost romantic innocence that “most judges [don’t] see themselves or the judiciary” as “unelected political officials or ‘junior varsity’ politicians themselves, rather than jurists.”

In perhaps the most revealing passages bearing on what Breyer means by “political” in connection with the work of the Court, he explains that the word brings to mind his time on the staff of the Senate Judiciary Committee chaired by Edward Kennedy. In that setting, Breyer observes, many choices were most sensibly made on the basis of who elected any particular official, to which major political party that official belonged, and which position was more popular with the voters on whom that official depended. Apart from Breyer’s failure to add the powerful factor of the official’s sources of funding and what positions those sources might be likely to support, this is a perfectly fine list.

But when he uses this same list to draw the conclusion that “politics in this elemental sense is not present at the Court,” Breyer exposes the shallowness of his definition. To be sure, politics “in this elemental sense” is unlikely to be present in a body whose members serve for life and have no pressing need to please either those who appointed them or those who might be generous to them in the future. When Breyer turns to “ideology, as apart from partisanship,” however, he acknowledges that this “is a tougher question, because we all have our predispositions.” Not to worry: if he ever catches himself “headed toward deciding a case on the basis of some general ideological commitment,” he knows he has “gone down the wrong path” and “correct[s] course,” as do his “colleagues,” all of whom “studiously try to avoid deciding cases on the basis of ideology rather than law,” something his experience tells him “is true of judges as a group, whether they serve on the Supreme Court or any other court.”

It’s hard to know where to begin deconstructing this self-serving series of what can only be called platitudes. For one thing, judges serving on lower federal courts have a different task from justices serving on the Supreme Court: if they want to avoid having their decisions reversed, as virtually all judges do, they must largely adhere to rules and precedents laid down for them from above. The skills and predispositions that enter into that task are far less dependent on what Breyer calls “ideology” than is the case for justices on our highest court, whose judgments can be reversed in matters involving constitutional interpretation only by the deliberately difficult—many think too difficult—process of amending the Constitution.

Beyond the differences between lower court judges and Supreme Court justices—whose task is more one of leading than of following and whose decisions are influenced but certainly not determined by precedent—Breyer seems oblivious to the well-known phenomenon that beliefs are shaped by what people want to think is the truth and to the commonplace understanding that people are rarely fully aware of what drives their decisions and actions.

Or maybe he isn’t all that oblivious: his recognition that “each judge must look to his or to her own conscience”—a source manifestly linked to one’s inner moral compass—to determine when to make compromises rather than insist on one’s own legal position reveals that Breyer, like most of us, understands that the exercise of judgment in difficult cases is invariably driven by currents more deep-seated than reference to any external source could explain. Indeed, his fascination with the works of Proust, whom he has called “the Shakespeare of the inner world,” is hardly consistent with the embarrassingly unrealistic suggestion that, upon noticing the influence of one’s worldview or general ideological orientation on one’s approach to a case, one need only “correct course” and return to the true path of the law.

Breyer condescendingly supposes that the reason “political groups so strongly support some persons for appointment to the Court and so strongly oppose others” is that they “typically confuse perceived personal ideology (inferred from party affiliation or that of the nominating executive) and professed judicial philosophy.” He tells us that judges who place “major interpretive weight upon the law’s literal text, for example,” might or might not “over time come to legal conclusions that we can characterize as more conservative.” But even when such judges do lean in a rightward direction,7 he insists that their “sworn duty to be impartial,” which he assures us all his colleagues “take…seriously,” should suffice to quiet doubt about whether politics, broadly defined, enters into their decision-making process.

Part of me—the part that respects Breyer as a highly sophisticated, indeed often brilliant, thinker and as the author of the most devastating and candid dissents of the modern era8—believes he may innocently hope that enough people will accept that notion to protect the Court from the loss of trust he fears it will incur once its inescapably political character is revealed for all to see. He seems so obsessed with what people think of the Court that he is willing to prioritize appearances over candor, even when it comes to the matter of individual justices explaining their views. Breyer sounds a bit like Emperor Joseph II criticizing Mozart for having “too many notes” in his musical compositions when he makes the disquieting suggestion that justices should avoid writing “too many dissenting opinions,” recommending instead that they join opinions with which they disagree, lest the public lose “confidence in Court decisions.”

In supposing that ordinary people cannot wade through what amounts to a handful of differing views, Breyer again reveals how dense he must think his readers are. This condescension becomes a regular theme in such lines as “the Constitution is a brief document” or when, in asking “where are judges and justices to find those ends, those ultimate objectives, that must guide them,” he answers, unhelpfully, “in the Constitution itself.”

To his credit, Breyer does offer some fairly sensible—if obvious—guidance to lay readers, including his insistence that students spend more time learning about civics and government, and his emphasis on the importance of civic participation to democracy. On the other hand, at a later point in his book he lays out banal nostrums to guide other judges, such as “Just do the job,” “Do not seek or expect popularity,” and “Clarity in writing is a professional necessity.”

This apparent contempt for his readers leaves me confused: For whom, exactly, is he writing this book? He tells us that his aim is to “supply background, particularly for those who are not judges or lawyers,” in part so that “those whose reflexive instincts may favor significant structural…changes, such as forms of court packing, think long and hard before embodying those changes in law.” Here, at least, Breyer is being candid: he is admitting that his book is in no small part a reaction to the mounting national call for enlarging a Court that many—including me—believe has been “packed,” by means of dubious legitimacy, with too many right-wing justices.

From comments that Breyer made on his book tour and in answer to journalists’ questions about why he wrote the book,9 we might conclude that one of his aims was to rationalize his persistent refusal to heed the lesson of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who gambled with the actuarial tables too long and thus enabled President Trump to choose a successor with a radically different judicial approach. It’s as though Breyer were telling everyone, both by remaining on the Court and by writing this book, “See, we judges aren’t influenced by politics—our own, those of the president who appointed us, or those of whoever will take our place. It’s law all the way down.”

Yet he is too savvy not to recognize that his announcement that he would retire at the end of the Court’s current term, in late June or early July, “assuming that by then [his] successor has been nominated and confirmed,” could not have looked more political. And far from being faulted for taking politics into account, Breyer has been widely praised for announcing his retirement early in President Biden’s second year in office, even though many of his ideological allies had urged him to retire earlier still. He could have made his announcement when he turned eighty-three, soon after the Court took its summer recess in 2021, a point at which President Biden and a Senate in Democratic control could have nominated his successor without the complications that the looming midterm elections might pose for a smooth confirmation. But of course there’s a world of difference between letting politics, even partisan politics, affect a judge’s personal decision when to leave the bench and letting political or ideological factors shape judicial decisions, as Breyer insists they do not.

A more plausible motive for writing this book—one Breyer revealed quite openly on his book tour—is his wish to discourage people from paying too much attention to the findings of the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States (of which I was a member), which submitted its report in December. The commission was charged by President Biden last April to assess public concerns about the Court and proposals to reform it. Yet Breyer offers no basis for evaluating his assertion that popular respect for the authority of the Court would be dangerously jeopardized by various proposed changes—such as enlarging the Court, limiting the terms of its justices, restricting its power to invalidate acts of Congress, limiting its discretion over which cases to review, altering its treatment of emergency matters on what has come to be known as its “shadow docket,” imposing a code of ethics, or requiring it to operate in a more transparent manner—whose merits he steadfastly refuses to address but whose adoption he darkly insists “could affect the rule of law itself.” Nor does his book meaningfully engage with any of these difficult questions:

(1) Does the ability of the Court to serve as a politically independent guardrail against despotism or anarchy actually depend on propagating the myth that its members are immune from influence by their cultural and political orientations and occasionally their partisan affiliations?

(2) To what degree is any such myth sustainable in the face of current experience? As Justice Sotomayor said acerbically, during the December 2021 argument in the abortion case Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the Court was earning the “stench…in the public perception that the Constitution and its reading are just political acts.” In his fine book The Case Against the Supreme Court (2014), Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the law school at the University of California at Berkeley, recalls that Sotomayor, like Chief Justice John Roberts, found it useful in her confirmation hearings to describe what justices do as “calling balls and strikes,” when in fact we know they do much more than that, including, as Chemerinsky notes, deciding the rules of the game and defining the strike zone.

(3) Finally, if a “balls and strikes” myth of apolitical adjudication is indeed sustainable, is attempting to sustain it morally justifiable? Put otherwise, is it an example of the Noble Lie we must tell ourselves in order to avoid disaster—or just another Big Lie that threatens our democracy?

As a member of the commission, I couldn’t help asking myself questions like these—or hoping that Breyer’s book would help us grapple with them. No such luck. I did sense in some of my fellow commissioners the belief that we’d best avoid being too open about our conviction that a majority of the justices had become dangerously wedded to a political perspective inherently hostile to the premises of a flourishing, inclusive democracy representing all persons equally, and that three members of that majority had been added to the Court by political processes that lacked democratic legitimacy.10 The general mood seemed to be that the Court should be spared the slashing critique I was coming to believe it deserved—a critique best put forward by Chemerinsky and in powerful testimony before the commission by the constitutional scholars Nikolas Bowie, Michael Klarman, and Samuel Moyn.11

These scholars made a persuasive case that throughout our history, and especially in its current configuration, the Supreme Court has by no means been a friend to politically underrepresented minorities, an ally to the rights of the least powerful among us, or a defender of the rights of all to full and equal participation in the project of self-government—the only reasons sufficient, in the minds of many, to warrant entrusting a power so vast to so politically unaccountable an institution. They have argued that giving the nation’s highest court not just the power of judicial review but of judicial supremacy—the final word on the meaning and application of a flawed but aspirational Constitution—has repeatedly been harmful to the cause of freedom and equality, with infamous decisions being the rule rather than the exception.12

Chemerinsky and the scholars who testified before the presidential commission have not been alone in their assessments. Justice on the Brink by the Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and now lecturer at Yale Law School Linda Greenhouse, the finest modern observer of the Supreme Court, does not take as panoramic a view of the Court’s role as these other scholars do and avoids the polemical cast of Breyer’s book. Instead, Greenhouse uses a single, pivotal year in the Court’s history as a strikingly revealing window into what it has become. Her book is a splendid account of how the Supreme Court that she covered for The New York Times for almost thirty years was on the verge in 2021 of cementing a profoundly undemocratic legacy.

It diluted voting rights in cases like Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, a 6–3 decision gutting what remained of the Voting Rights Act. It eroded the wall separating church and state in cases like Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, in which the Court accepted a Catholic social service agency’s religious liberty challenge to the city’s termination of its contract because the agency violated the contract’s antidiscrimination requirement by refusing on religious grounds even to consider same-sex married couples as foster parents.13 It undermined the autonomy of women as fully equal citizens in a series of decisions dealing with abortion. Greenhouse recognizes these decisions as foreshadowing the Court’s disingenuous approach to the recent Texas law outlawing all abortions taking place after the first six weeks of pregnancy, but deviously removing almost all state officials from the law’s enforcement in order to make it virtually impossible to challenge in federal court.

In her analysis of Brnovich, Greenhouse dissects the briefs and oral arguments with scalpel-like precision. She follows the history of both the Voting Rights Act and the case itself, laying bare the logical tricks underlying Justice Samuel Alito’s “grudging and ahistorical” majority opinion to demonstrate just how disingenuously and profoundly it ignored the purposes of the Voting Rights Act. And in a discussion that could not contrast more starkly with Breyer’s obfuscatory approach, Greenhouse says that “of course Fulton v. City of Philadelphia had almost everything to do with politics.”

Greenhouse took great care while reporting on the Court’s decisions over the decades to keep her own opinions of their merits to herself. In this masterly book, she continues that restraint, but she is far more forthright now in describing the apparent influence of the religious backgrounds and affiliations of the justices, six of whom are Catholics, one of whom is Protestant, and two of whom are Jews, and in identifying the powerful influence of the right-leaning Federalist Society and even more right-leaning individuals and groups that have financed the four-decade project of turning the federal judiciary in general, and the Supreme Court in particular, toward the hard right.

She perceptively explores the appointment of Barrett, an avowedly antiabortion and indeed anticontraception jurist. Barrett was nominated by President Trump to the seat that had been occupied by Ginsburg, a legal pioneer in the quest for gender equality, less than two months before the presidential election and only a week after Ginsburg’s death. Justice Barrett, who has greater tact than Justices Gorsuch and Alito and thus will perhaps have a longer-lasting impact on the Court’s rightward turn, is revealed by Greenhouse to be a substantial threat to democratic values.

Through most of the Court’s history, we have seen it rule in ways that undermine those values. The only significant exception was the remarkable period from the mid-1950s to the late 1970s. Today the Court appears once again set on an antidemocratic trajectory, one more deeply entrenched and less amenable to a change in course. In light of that dismal prospect, I hoped that something in Breyer’s book could enable me to join those who continue, in the face of their apprehensions, to sing the praises of the Court as an imperfect but nonetheless admirable institution rather than endorse Justice Sotomayor’s remark about the “stench” of its politicized decisions. Far from it. Unfortunately, Breyer’s failure to grapple with the Noble Lie—as part of a candid appraisal of the current Court’s threats to law and reason—comes at a moment when another lie looms.

The “Big Lie” that the 2020 election was stolen and that the administration governing the nation is illegitimate menaces the future of the Supreme Court and our republic, threatening to deceive the populace while the cynical enablers of a charismatic despot seize power, aided and abetted rather than halted by a Court whose composition he has radically altered. I wish we could take solace from the fact that even this Court has turned back several attacks on the operations of government so manifestly lacking in legal substance that any other result would have been an obvious embarrassment, but I fear we cannot.14 Such decisions reveal only that the justices are, in the end, masters of their craft and know that their power requires them to act as lawyers. But the sad truth remains that law’s constraints are no match for power’s voracious appetite.

In his book On Tyranny (2017), the historian Timothy Snyder offers this as the tenth of his “twenty lessons from the twentieth century”:

Believe in Truth: To abandon facts is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power, because there is no basis upon which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle.

At this moment, it falls to each of us to preserve truth wherever possible and to call out falsehoods however comforting. Breyer’s book has left me more persuaded than ever that we have more to lose than to gain by continuing to praise the Court even when we see the trajectory of its decisions as destructive of what we hold most dear about our constitutional order.

—February 10, 2022

This Issue

March 10, 2022

What We Owe Our Fellow Animals

Covid’s Economic Mutations

-

1

See, for example, Breaking the Vicious Circle: Toward Effective Risk Regulation (Harvard University Press, 1993); Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution (Knopf, 2005); Making Our Democracy Work: A Judge’s View (Knopf, 2010); and The Court and the World: American Law and the New Global Realities (Knopf, 2015). ↩

-

2

Sissela Bok has written perceptively about the moral philosophy of deception. See her Lying: Moral Choice in Public and Private Life (Pantheon, 1978). For a sophisticated if not altogether convincing defense of judicial self-deception, see Scott Altman, “Beyond Candor,” Michigan Law Review, Vol. 89, No. 2 (November 1990). ↩

-

3

Along with other colleagues from Harvard Law School, I published a tribute to Justice Breyer to honor his first twenty years on the Court: “Peek-A-Boo: Justice Breyer, Dissenting,” Harvard Law Review, Vol. 128, No. 1 (November 2014). ↩

-

4

The seminal work is Gerald N. Rosenberg, The Hollow Hope: Can Courts Bring About Social Change? (University of Chicago Press, 1991). ↩

-

5

My own contribution to that mountain, as someone who cannot claim to be a disinterested observer (I argued the first of the two Supreme Court cases culminating in Bush v. Gore), included “eroG.v hsuB and Its Disguises: Freeing Bush v. Gore from Its Hall of Mirrors,” Harvard Law Review, Vol. 115, No. 1 (November 2001); reprinted in Bush v. Gore: The Question of Legitimacy, edited by Bruce Ackerman (Yale University Press, 2002). ↩

-

6

The best account is Pamela Karlan, “The New Countermajoritarian Difficulty,” California Law Review, Vol. 109, No. 6 (December 2021). See also Thomas B. Edsall, “Whose America Is It?,” The New York Times, September 16, 2020. ↩

-

7

The most dramatic modern counterexample, Justice Gorsuch’s majority opinion for a 6–3 Court in Bostock v. Clayton County (2020), surprised most Court observers when it treated the Title VII ban on discriminating “on the basis of sex” as literally covering antitransgender discrimination. Chief Justice Roberts joined the majority; Justices Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Kavanaugh dissented. ↩

-

8

See, for example, his dissents in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 (2007): “To invalidate the plans under review is to threaten the promise of Brown. The plurality’s position, I fear, would break that promise. This is a decision that the Court and the Nation will come to regret…. I must dissent”; and in NFIB v. Dept. of Labor (2022), which concerned occupational safety rules regarding Covid in the workplace: “The majority…substitutes judicial diktat for reasoned policymaking…squarely at odds with the statutory scheme…. Without legal basis, the Court usurps a decision that rightfully belongs to others.” ↩

-

9

A recent example was Breyer’s interview with CNN Supreme Court reporter Joan Biskupic. ↩

-

10

The final report of the commission, which in accord with President Biden’s charge made no policy recommendations but only described the history of various reform proposals and analyzed them, summarized this perspective on pp. 74–79. Even though the arguments for Court expansion were noted, the need to generate a consensus document that all thirty-four commissioners could agree to submit to the president without any published dissents invariably led to relatively anodyne statements of those arguments. ↩

-

11

Nikolas Bowie, “The Contemporary Debate Over Supreme Court Reform: Origins and Perspectives,” June 30, 2021; Michael J. Klarman, “Court Expansion and Other Changes to the Court’s Composition,” July 20, 2021; and Samuel Moyn, “Hearing on ‘The Court’s Role in Our Constitutional System,’” June 30, 2021. ↩

-

12

For example, Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), denying citizenship and full personhood to Black slaves and their descendants; Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), upholding “separate but equal” public facilities for Blacks and whites; Korematsu v. United States (1944), affirming the wartime power of the president to round up and relocate American citizens of Japanese ancestry without proof of subversion or disloyalty; Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010), striking down virtually all legislative efforts to limit corporate spending and contributions in political campaigns; and Shelby County v. Holder (2013), striking down the provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that required state and local voting changes with obvious discriminatory potential to be submitted for approval by the Justice Department. ↩

-

13

Greenhouse explains—as only someone so steeped in the Court’s history and so adept at reading between the lines could—the way Barrett, the newest justice, opted to side with Chief Justice Roberts over Justice Alito to yield a 5–4 decision in the Catholic agency’s favor that paved the way to weakening the separation of church and state in subsequent cases without prematurely tackling precedents that stood in the way, as Alito was eager to do. ↩

-

14

A recent example is Trump v. Thompson (2022), an 8–1 unsigned opinion requiring the National Archives to turn over Trump’s presidential papers to the House special committee investigating the January 6, 2021, insurrection because “President Trump’s claims would have failed even if he were the incumbent president…and under any of the tests he advocated” in light of the committee’s urgent need for the materials sought. ↩