How do we respond to barbarians at the gates? On February 25, 2022, as Russian troops invaded her country, the young Ukrainian congresswoman Kira Rudik tweeted, “I learn to use #Kalashnikov and prepare to bear arms.” When the Nazis invaded France in 1940, the physicist and Nobel laureate Frédéric Joliot-Curie smuggled his working papers out of Paris but stayed behind to help lead the Resistance, turning his scientific talents to the manufacture of Molotov cocktails. The ancient historian Livy tells us that in 390 BCE, as a troop of Gauls bore down on Rome, the most distinguished senators among those too old to fight and too proud to flee dressed in their most elaborate togas. Each one sat in silence in the atrium of his own house, on the ivory throne that symbolized his high office, his hands holding the insignia of imperium—high command. At first the old men’s surreal tranquility cowed the invaders, but when a Gaul stroked the beard of a senator and was smacked in return by an ivory mace, the raiders realized that these men, too, were human and massacred every one. In Hans von Trotha’s haunting novel Pollak’s Arm, published in Germany in 2021 and now beautifully translated into English by Elisabeth Lauffer, the setting is Nazi-occupied Rome on October 16, 1943, the Saturday when the Gestapo rounded up the city’s Jews—the day when the barbarians came knocking door to door.

German troops had seized the city only a month earlier, on September 10. The Italian prime minister, Marshal Pietro Badoglio, and King Victor Emmanuel III had fled on the ninth—one day after the truce Italy had signed with the Allies on September 3 became public knowledge—and taken refuge behind Allied lines in southern Italy. The Nazis wasted no time in going about their brutal business in Rome because they had no time: Germany had been defeated at Stalingrad in February and faced a slow but inexorable Allied advance up the Italian peninsula. A Nazi commando unit sprang Mussolini from his Italian prison on September 12 and set him up with a puppet regime, the Italian Social Republic, at Salò on the shores of Lake Garda, far enough north to buy them both time.

In Rome, however, SS officer Herbert Kappler worked swiftly to impose a reign of terror as the Eternal City’s new chief of security police, his attention fixed on Communists, anarchists, Roma, and, above all, Jews. On September 26, he summoned two heads of the Jewish community to his office on Via Tasso and informed them that “we will not deprive you of your lives if you do what you are asked. With your gold we want to equip new armies for the Fatherland. Within 36 hours you must provide 50 kilograms of gold.” Otherwise, he threatened, he would deport two hundred Jews to the Russian front. The community delivered eighty kilograms to Via Tasso on September 28, convinced that the tribute would guarantee their safety.

In early October, however, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler entrusted Italy to Theodor Dannecker, who had coordinated the deportation of Jews from France, Macedonia, and northern Greece and would move on to Hungary. At 5:30 on the morning of October 16, 365 Gestapo men sealed off the former Roman Ghetto and delivered a mimeographed sheet of paper to its Jewish families, giving them twenty minutes to pack “for eight days” and assemble in front of the ancient Portico of Octavia. Other detachments sought out the more affluent Jews scattered elsewhere in the city. By 2 PM, more than 1,200 people had been loaded on trucks and taken to the Collegio Militare in Trastevere. Some two hundred were released as non-Jews on closer examination of their papers, but on October 18 those remaining—more than a thousand people—were crammed into cattle cars at the Tiburtina railroad station and dispatched to Auschwitz by way of Padua and Vienna. (In Padua, bystanders reported their appalling condition and forced the SS guards to let the prisoners get water.) Of those deported, fifteen men and one woman returned to Rome after the war. None of the children survived.

The narrator of Pollak’s Arm, known only as K., is “a secondary school teacher from Berlin stranded in occupied Rome and harbored in the Vatican.” It is October 17, 1943, and he has just arrived at the office of Monsignor F. in “a building near the German cemetery Campo Santo Teutonico,” a sufficient clue to identify it as the German College (Collegio Teutonico) within Vatican City. Here, during World War II, a courageous Irish priest, Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty, used his office as papal chamberlain to set up a rescue network, the Rome Escape Line, that saved some 6,500 people from certain death. Monsignor F., “a retired prelate and ecclesiastical diplomat whose German is flawless, virtually accentless except for a trace of Italian inflection,” is a member of O’Flaherty’s operation, and K. has come to report what occurred the day before, when he had been charged with bringing the Jewish archaeologist Ludwig Pollak and his family to safety in the Vatican.

Advertisement

The people of von Trotha’s novel are real. Pollak was one of the most colorful characters among the many expatriates who found themselves in early-twentieth-century Rome. Prague-born, educated in Vienna at its famous Archaeological-Epigraphic Seminar, he reached the Eternal City in 1893 and set up shop as an art dealer of wide interests and exquisite taste. His work as a consultant for the wealthy collector Senator Giovanni Barracco eventually led to his appointment as the director of Barracco’s Museum of Comparative Ancient Sculpture (featuring some two hundred Greek, Roman, Etruscan, Assyrian, Egyptian, and Cypriot objects, as well as some choice medieval works).

Barracco donated this distinctive collection to the city of Rome in 1902 in exchange for the rights to a plot of land at the end of the new Corso Vittorio Emanuele II. The Museo Barracco opened in 1905 but fell victim to Mussolini’s schemes for urban renewal in 1938, just one of the demolitions that heralded the successive incarnations of New Rome in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Pollak, when K. comes to fetch him, has seen too many of them:

His presence is as awe-inspiring as ever, the way he holds your gaze with those piercing eyes. However, he seems weakened by pain, I myself was pained to see. How old do I reckon he is? Mid-seventies, I’d say. Yes, he must be in his mid-seventies.

Quick, we must leave for the Vatican this instant—you, your wife, your daughter and son. Everything’s been taken care of; we just have to go downstairs. The car is waiting.

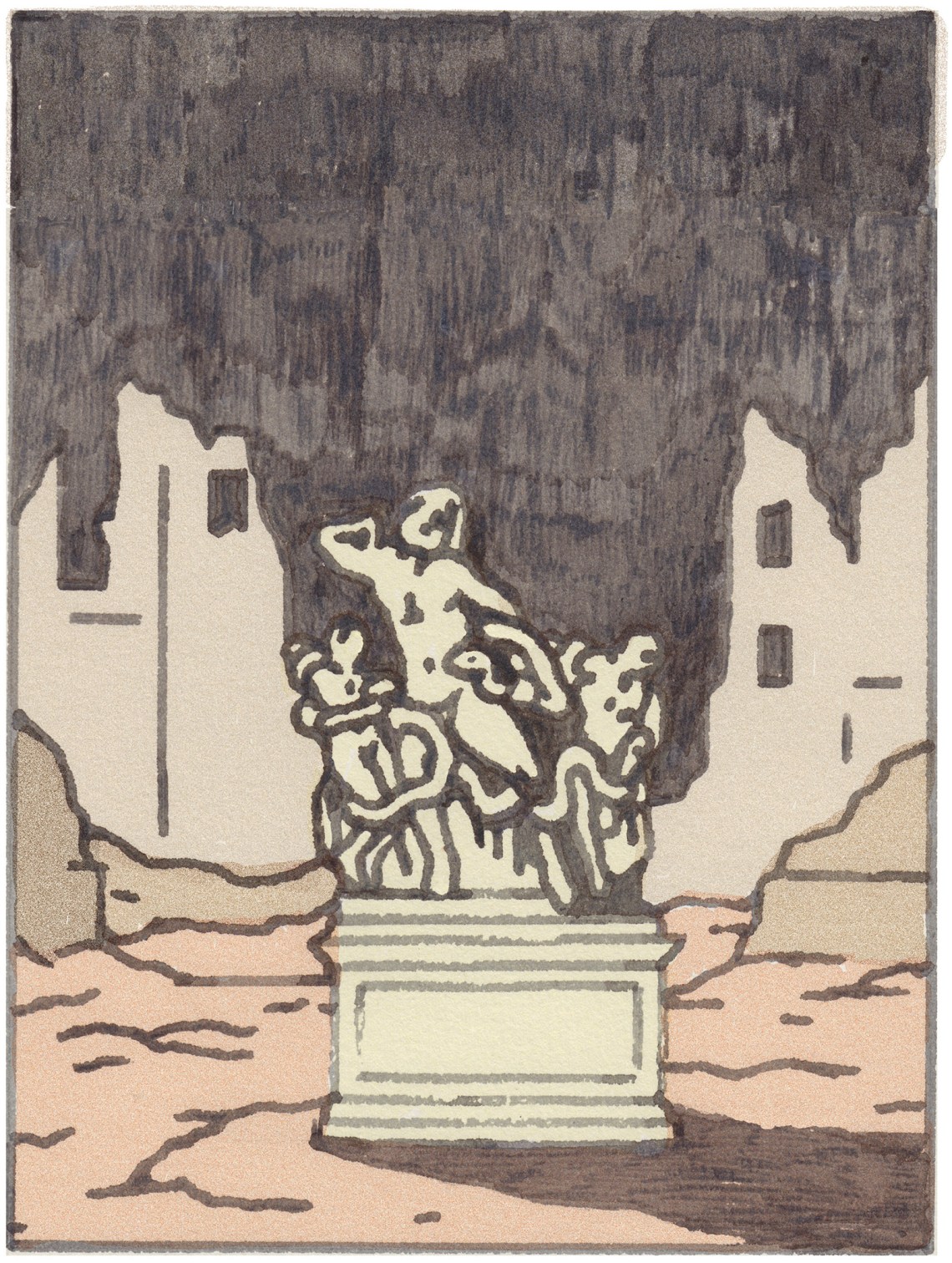

But Pollak, as calm as those ancient Roman senators before the invading Gauls, chooses instead to talk, to take K. on a long tour through his memories. We hear spellbinding tales of Rome as it was in the first flush of the Kingdom of Italy; of Pollak’s long-demolished studio on the Via del Tritone with its frescoes by the eighteenth-century painter Giovanni Paolo Pannini, the sanctum where he played host to so many works of art and so many distinguished collectors; and of the great discovery that marked the triumph of his career. In 1906 Pollak recognized the battered marble carving of a bent elbow in a stonecutter’s shop as the missing arm of one of the world’s most famous ancient sculptures: a statue of the Trojan priest Laocoön and his two sons being throttled by snakes. It had been unearthed in the ruins of the Golden House of Nero in 1506, requisitioned for the Vatican’s collections by the papa terribile Pope Julius II, and restored by Jacopo Sansovino—who added an arm outstretched rather than bent back, replaced in 1532 by Giovanni Antonio Montorsoli’s still-straighter version.

K. listens, half-enthralled and half-impatient, petrified as time and opportunity tick away and the danger increases by the second. Pollak’s sole concern is to testify—to his vanished world and his vanished life, to the enduring beauties that will survive even this cruelty, this ugliness, like the Colosseum as it is now, bleached clean of the suffering of the animals and people sacrificed to ancient Rome’s unspeakable public spectacles:

He gets caught up in pathos sometimes, K. says, and he’ll start using dated language or unbridled gestures. I think his emotions get the better of him. He also wants to share, and thereby preserve, whatever is unleashing these feelings, including the force with which it does so. Pollak erects monuments with such phrases, and in Pollak’s world, monuments serve as milestones, whether of cultural progress or an individual life. They are what counts.

The Laocoön group provides von Trotha’s Pollak with a monument freighted with as many layers of significance as Rome itself. In Vergil’s Aeneid, Laocoön, in his authority as priest of Neptune, warns his fellow Trojans not to accept the gigantic wooden horse that their Greek adversaries have mysteriously left on the beach. “I’m afraid of Greeks even when they’re bringing gifts,” he declares (timeo Danaos et dona ferentes). Swiftly, troublemaking Minerva sends a pair of supernatural snakes to rid Troy of this turbulent priest, with results that Vergil describes in lurid detail (here in John Dryden’s translation):

And first around the tender boys they wind,

Then with their sharpen’d fangs their limbs and bodies grind.

The wretched father, running to their aid

With pious haste, but vain, they next invade;

Twice round his waist their winding volumes roll’d;

And twice about his gasping throat they fold.

The priest thus doubly chok’d, their crests divide,

And tow’ring o’er his head in triumph ride.

With both his hands he labours at the knots;

His holy fillets the blue venom blots;

His roaring fills the flitting air around.

Thus, when an ox receives a glancing wound,

He breaks his bands, the fatal altar flies,

And with loud bellowings breaks the yielding skies.

The marble sculpture depicting the “doubly chok’d” seer and his “tender boys” may date from the same time as Vergil: the age of Augustus, who reigned from 31 BCE to 14 CE. It is probably the same work praised two generations later by the Roman writer Pliny as the creation of three sculptors from Rhodes—Agesander, Athenodorus, and Polydorus—but Pliny gives no indication of its date or the patron who commissioned it. Scholars continue to debate when it was created (possible dates range over some three hundred years, from 200 BCE to the 70s CE) and whether it is a precise copy of a lost bronze original or an elaborated version.

Advertisement

To Michelangelo, who rushed to see the statue as soon as it was discovered, the priest’s exaggerated muscles and anguished expression revealed heroic new ways to portray human endurance. Laocoön in his agony embodies everything that separated “bread-eating mortals” from the gods of antiquity. He has stood in the Vatican since 1506 next to one of those marble divinities, the lithe, elegant Apollo Belvedere, as graceful as Laocoön is contorted, as youthful as Laocoön is aged, as blithe in his arrogance as Laocoön is racked by suffering. Renaissance sculptors often claimed that the Laocoön group had been carved from a single block of marble, but Michelangelo certainly knew better, and so, probably, did everyone else who took a close look and saw the carefully crafted joins. But the challenge of producing a three-in-one statue appealed irresistibly, and around 1512 another Tuscan sculptor based in Rome, Andrea Sansovino, carved just such a marvel: a Virgin, Child, and Saint Anne, still on view in the church of Sant’Agostino.

Laocoön, who saw so clearly, provides a powerful image of impending doom, but Pollak, the first modern person to imagine the sculpted Laocoön in its original form, seems to resist acknowledging his own dire situation. K. urges the elderly archaeologist to act:

We know how this journey ends, though, I responded. That’s why I’m here.

With all due respect, Pollak countered, even the highest authority among those who sent you does not know what the future truly holds. The here and now is not his concern; it is the hereafter, which in my case does not apply. Although—

He didn’t finish the sentence.

But, he added, please convey my sincerest thanks to everyone in the Vatican. Yes, he said, I am touched that they sent you.

In 1766 Gotthold Ephraim Lessing used the Laocoön group, which he had seen only in engravings, to engage in philosophical battle with Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who had seen the real statue, albeit outfitted with its Renaissance arm rather than the original. Winckelmann’s Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (1755) had asserted that Laocoön, befitting his own idea of Greek art as a triumph of “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur,” exhibited the “anxious and subdued sigh described by [the Renaissance poet Jacopo] Sadoleto” rather than Vergil’s “loud bellowings.” To Lessing, comparing a work of sculpture to a poem was an exercise in nonsense. In Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry, he insisted that each art retains its own distinctive character; hence Vergil’s poetry and the ancient sculpture set for themselves, and achieve, entirely different expressive aims. Neither illustrates the other, nor can it, for each is an entirely independent creation. Laocoön’s pain, moreover, is anything but subdued: it is explicit.

Von Trotha’s Pollak, in turn, believes that his discovery of Laocoön’s bent arm has entirely changed the meaning of the statue. The outstretched arm, reaching upward through the chaos, expressed the priest’s extremities of suffering as an epic struggle toward immortality. The bent arm, the real arm, has brought Laocoön and his agony crashing back down to earth, bound by the incurable pain of being human:

He’s no hero, and neither nobility nor grandeur is on display. Simplicity, maybe. And a bloodcurdling scream ringing in the silence….

The extended arm is monumental, sublime, and wrong. The arm that will never reach out again. My arm—the arm of a doomed man—that is the real arm.

K. fidgets, and still Pollak spins out his siren song as the light of day begins to fade (von Trotha has taken that small liberty with the facts—the Gestapo may have wrapped up operations just before a late lunch, but his version of Pollak’s story requires the light of a setting sun):

He turned and looked me straight in the eye. One must give a personal account, he said. Particularly when the end is imminent. One must tell stories. One must write them down. One must ensure that memory remains, so that others might remember when you no longer can.

Pollak’s memories are indissolubly linked to the glorious, weighty heritage of Judaism, and hence to anti-Semitism, the serpent that has confined him in its coils since his birth, a monster unleashed by an angry God for some unfathomable reason—or perhaps the same reason that drove Minerva to throw snakes at Laocoön: to stifle a seer’s second sight. From an earlier encounter with Alfred Dreyfus to his gradual exclusion from every aspect of contemporary Roman life amid Germany’s, and then Italy’s, growing compliance with Adolf Hitler’s racial doctrines, Pollak’s devotion to beauty has been wrung at the price of a constant battle against ugliness and evil. One of the unkindest cuts occurred in 1935, when he was denied entry to the great art-historical library founded in Rome by the Jewish benefactress Henriette Hertz as a place where women could read alongside men. “I was the first and most faithful visitor the Hertziana ever had,” Pollak tells K. “And then—”

Yet Pollak’s long soliloquy ends with apparent denial. He tells K., “They will not come for me tomorrow.” And they didn’t. They came that same day.

The Gestapo arrested Pollak and his entire family, corralled them in the Collegio Militare with more than a thousand other prisoners for two hellish nights, and then sent them off to the ultimate hell of Auschwitz. Like the senators of Rome in 390 BCE, von Trotha’s Pollak discovers that his noble stand could hold off the barbarians only to a certain point, but the story of that stand, that refusal to bend to barbarism, would outlive them all.

The Gestapo’s roundup, or rastrellamento, of October 16, 1943, lives in infamy. But as a military operation it failed in its objectives, which were to deport eight thousand people, not one thousand, and to terrorize the Romans, who instead resisted the Nazis more stubbornly than ever. Before the trucks arrived, Roman Jews had been warned to take refuge in the countryside, and many did. Others escaped the Gestapo’s net by climbing over rooftops or knocking on their neighbors’ doors. Hundreds hid in out-of-the-way corners of churches and convents, in private homes, or within the walls of the Vatican with the help of Monsignor O’Flaherty and his associates. One man simply got into a Roman cab; the driver spent the rest of the day chauffeuring him around the city and saved his life.