If what you want is on the other side, a closed door might become an image of your desire. In ancient Greek poetry, this motif had a name: paraclausithyron, “a lament beside a door.” In Latin poetry it was called exclusus amator, “excluded lover.” “Closed doors are useful,” complained Ovid in the Amores, “as a defense for besieged cities, but why, in times of peace, do you fear arms?” “Unscrew the locks from the doors!” Whitman demanded in “Song of Myself.” “Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!” In moments like these, the closed door is not merely a barrier; it becomes a screen onto which longing is projected—and thereby made plain for all to see.

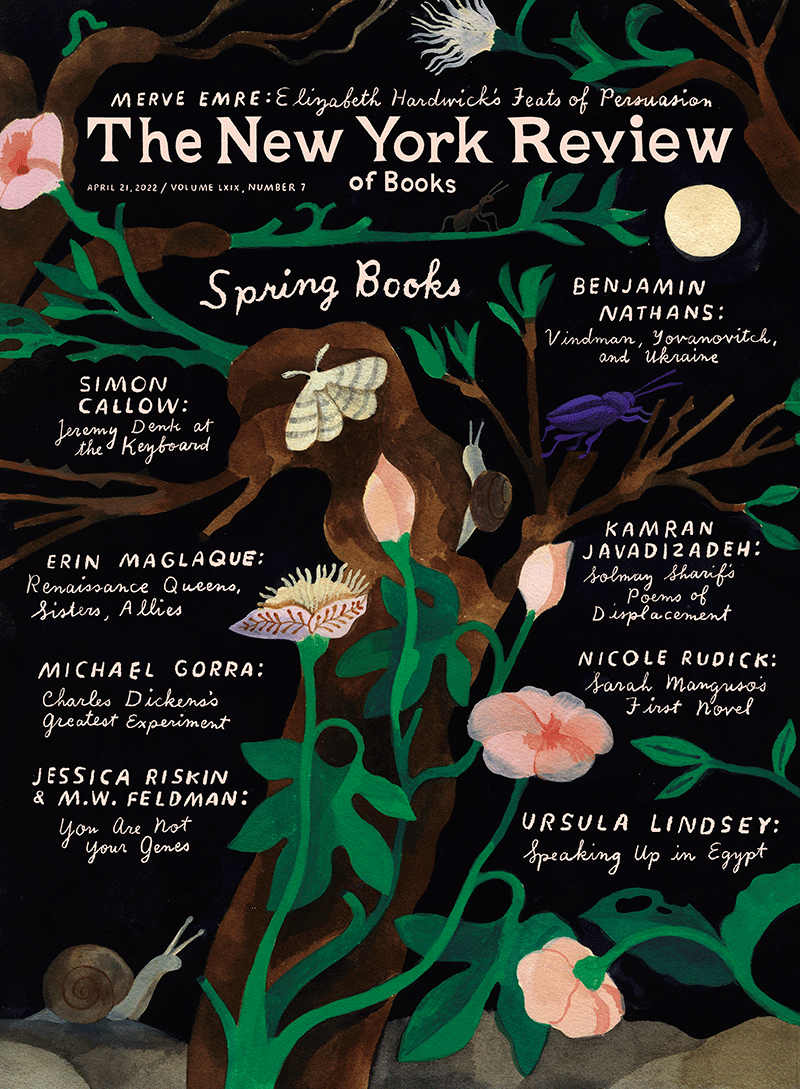

Closed doors are everywhere in Solmaz Sharif’s second collection of poems, Customs. What can they tell us about what this poet wants? Sometimes, as in the examples above, the doors prevent the consummation of erotic desire: “One against whose door//I knocked, still knock/to be let in, beloved.” But elsewhere that desire “to be let in” moves beyond the merely erotic and suggests a wish (however frustrated or ambivalent) for other kinds of inclusion, reunion, and affiliation.

Ancient though the motif may be, Sharif’s closed doors point to new possibilities for the lyric. For at least the last two centuries, it has been customary to imagine the lyric poet as solitary, as a voice speaking to itself, whose words readers can only rehearse in their own solitude. This is how John Stuart Mill distinguished between poetry and mere eloquence: “Eloquence is heard; poetry is overheard.” Citing a Burns lyric (“My Heart’s in the Highlands”) that seemed to him to epitomize poetry’s fundamental nature, Mill concluded, “That song has always seemed to us like the lament of a prisoner in a solitary cell, ourselves listening, unseen, in the next.” Sharif’s poet, like Mill’s singer, is aware of her solitude. But she’s also aware of the conditions that have produced it.

Asked recently to comment on one of her new poems, Sharif wrote, “Every once in a while, I try to consider the original thorn that begets my writing. It shifts, this thorn, but this is one: the hours spent waiting at international terminals.” An airport might seem an unlikely place to find the muse. But what waiting in those terminals has revealed, according to Sharif, is the tight weave of biography and history, the way the forking paths of particular lives have had to bend to the cold demands of the nation-state: “And how this wait reminds you of the threat your being together poses on a national level. How it is to recognize then the ‘might have otherwise been’ of your imagined life.” Precisely because international terminals are such highly regulated spaces, they make visible the fantasies of freedom held by the exhausted travelers passing through their checkpoints, the anxious desires of those waiting, on the other side, for a glimpse of the arrivals. The airport, in this sense, can feel like another closed door.

What is behind that door? How might life otherwise have been? Sharif was born in 1983 to Iranian parents in Turkey and grew up, from her infancy, in the United States. Those basic facts—and the inevitably varied and complex life that has unfolded from them—have had to accommodate others: in 1953, MI6 and the CIA, seeking to secure Anglo-American claims to Iranian oil, orchestrated a coup in Iran, laying the groundwork for decades of autocratic rule by the Shah;1 in 1979 that same Shah was overthrown in the Islamic Revolution; between 1980 and 1988, Iran and Iraq fought a bloody war in which the US provided financial support and military hardware to Iraq; since 1979, the US has imposed a series of nearly constant, interlocking sanctions on Iran; in 2017 Donald Trump issued first one and then another executive order banning travel from Iran to the United States. “According to most/definitions, I have never/been at war,” Sharif once wrote. “According to mine,/most of my life/spent there.”

Sharif’s first book, Look (2016), in which those defiant lines appeared, diagnosed the abuses of language that had helped to make that war invisible, or in any case palatable, to most of the Americans in whose names it was waged. She plumbed the United States Department of Defense’s Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms for a lexicon of ordinary English words that had been redefined as military jargon. These are in small caps throughout Look: seemingly benign words like scan, distance, draft; portentous phrases like continuous strip imagery, permanent echo, catastrophic event. Often they crop up in domestic scenes, far from any obvious battlefield, as in this description of the poet’s father: “his eyes//SENSITIVE when he passes advice to me, like I’m his//SEQUEL, like we’re all a//SERIAL caught on Iranian satellite TV.” The implication is that American imperialism has underwritten even the domestic life of an Iranian family living in the United States.

Advertisement

At its farthest reaches, Look gestures toward another life, dimly perceived in an imagined space and on an alternate timeline. In “Personal Effects,” the collection’s longest poem (its title alludes to a soldier’s possessions, the local consequences of global conflict, and the literary production of private feeling), that space is again found in the liminal zone of an airport:

As if a film projection caught

in theater dust, I play itout: I approach you

in the new Imam Khomeini Airport,

fluorescent-lit linoleum, you walk up

to meet me, both palms

behind your back

like a haji. You stoop, extend a handHello. Do you know who I am?

The “you” whom the poet approaches in this passage is a ghostly version of Sharif’s paternal uncle (in Farsi, her amoo), a draftee who died in the Iran–Iraq War shortly before the poet was born—and decades before the Imam Khomeini Airport opened. The poem is, among other things, a fantasy of recognition, the restoration of a bond that never had a chance to form. Sharif’s metaphor for this kind of fantasy is cinema, which allows for provisional immersion in collectively held fiction, but here what makes possible that fictional world—the uncle who returns from death as though from pilgrimage, the niece (at her desk, in the airport) who answers him, “Yes, Amoo”—is not film but the double life, the “as if,” of poetry.

Sometimes that double life can feel like no life at all. That feeling is a recurrent preoccupation of Sharif’s enthralling new collection; this is, Customs seems to say, what it has been like to exist on both sides of a closed door. The volume’s first poem is also printed on its back cover. Called simply “America,” its thin strip of lines testifies to the price of having passed through that narrow door into this country, without ever having resolved the desire for what lay on its other side:

I had

to. I

learned it.

It was

if. If

was nice.

I said

sure. One

more thing.

One more

thing. Eat

it said.

It felt

good. I

was dead.

I learned

it. I

had to.

Enjambments betray the ambivalence of these declarations. The poem’s simple first sentence—“I had/to.”—might at first, because of the line break, imply that this “I” is making a statement about what, at some undefined point in the past, she possessed: I had a home, I had a family. But the second line, which completes the sentence, transforms that possibility into a statement of compulsion. The rest of the poem unfolds the implications of that dispossession: the speaker’s learned acquiescence (“I said/sure”), the recursive nature of the nation’s demands (“One/more thing./One more/thing.”), the narcotic allure of being taken in (“It felt/good. I/was dead.”). “America” ends with a chiastic reversal of its first two lines, just as the poem itself is printed first and last in the book. These are first words that are also last words; a poem of entry and a poem of exit—the speech of someone who has been reduced almost to nothing.

What is it like, that almost? What “I” is possible under such conditions? These are questions, for Sharif, about the power of poetry, its limits and affordances. In the poem “He, Too,” the questions are dramatized in another airport scene, a conversation between the poet “upon [her] return to the US” (a pun that suggests the contingency of her inclusion in the American first-person plural) and the US Customs and Border Protection officer who interrogates her:

What do you teach?

Poetry.

I hate poetry, the officer says,

I only like writing

where you can make an argument.Anything he asks, I must answer.

This, too, he likes.

The traveler looks powerless as she faces this agent of the state. He is a brutish avatar of Marianne Moore’s ironic position in “Poetry,” which famously begins, “I, too, dislike it”—one source, perhaps, for Sharif’s title (he, too, dislikes poetry). The officer compels her speech even as he devalues its form. But the poet holds her own kind of power in abeyance. What she doesn’t tell him, she shows us:

I don’t tell him

he will be in a poem

where the argument will beanti-American.

Poetry gives Sharif the power to turn the words of the state back onto itself; it is, despite the distinction the officer wants to draw, what Emerson once called “a metre-making argument,” a way of casting thought into being.

But if Moore is one source for the poem’s title, then Langston Hughes is another: “I, too, sing America.” As Hughes’s biographer Arnold Rampersad explains, Hughes wrote that poem in 1924 after his passport had been stolen, leaving him stranded in Genoa, unable for a period of weeks to secure passage on racially segregated ships back to the US. For Hughes as for Sharif, in other words, admission into the American body politic is contingent on the accommodations one can make to the claims of whiteness—or else on poetry’s capacity to imagine a different kind of belonging.2

Advertisement

At the airport, the officer can hold the traveler at his discretion, but, in her poem, the poet can do the same to the officer:

I place him here, puffy,

pink, ringed in plexi, pleasedwith his own wit

and spittle.

This is a version of what J.L. Austin called “performative” language—its utterance constitutes the action that it names. The racism that had structured the encounter is transformed into poetic justice; the whiteness of the officer, which had formerly signified his smug power, now, in a series of alliterative plosives (puffy, pink, plexi, pleased), marks his denuded state, makes him exhibit A in the poem’s demystifying argument. That grants Sharif, in her poem’s last lines, a measure of freedom: “Saving the argument/I am let in//I am let in until.” “He, Too,” which Sharif has said was “written in between immigration bans,” was first published on the website of the Academy of American Poets; the traveler at the airport and the poem she goes on to write have both gained entry, in other words, into respectable, national institutions. But the poem ends without any final punctuation, which suggests that both forms of inclusion have been provisional.

Sharif faces a paradox: the language in which she writes her poems has also been the site of her dispossession. A poem titled “The Master’s House” is a relentless litany of accommodations, large and small: “To let go of the grudge,” “To revel in face serums,” “To disrobe when the agent asks you to.” In its final lines, that paradox becomes a crisis for life and for poetry:

To recall the Texan that held a shotgun to your father’s chest, sending him falling backward, pleading, and the words came to him in Farsi

To be jealous of this, his most desperate language

To lament the fact of your lamentations in English, English being your first defeat

To finally admit out loud then, I want to go home

To stand outside your grandmother’s house

To know, for example, that in Farsi the present perfect is called the relational past, and is used at times to describe a historic event whose effect is still relevant today, transcending the past

To say, for example, Shah dictator bude-ast translates to The Shah was a dictator, but more literally to The Shah is-was a dictator

To have a tense of is-was, the residue of it over the clear bulb of your eyes

To walk cemetery after cemetery in these States and nary a gravestone reading Solmaz

To know no nation will be home until one does

To do this in order to do the other thing, the wild thing, though you’ve forgotten what it was

The grammatical example is telling: English wants to relegate the Shah’s dictatorship to the past, whereas Farsi carries a different view of history, in which Iran’s postrevolutionary reality cannot be described except in light of the autocratic rule that preceded it and that was sponsored by the world’s two most powerful anglophone countries. Such grammars structure our lives. To read the tombstones in a nation’s cemeteries is to contemplate the boundedness of life within its borders.

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”: Audre Lorde’s dictum about the inability of white feminist theory to intervene meaningfully in the lives of Black women provides Sharif with her poem’s title and with a description of something like the bind she is in. Poetry—or rather the poetry she can write, which is to say poetry in English—seems, at the end of this poem, no more than a diversionary tactic. And the danger inherent in such tactics is that they become our lives.

How can a poet escape this bind? One answer might be to go home. But the poems in Sharif’s new book acknowledge the impossibility of satisfying diasporic nostalgia. There is a poem in Customs called “Learning Persian” whose every line is simply a phonetic transliteration of a Farsi word that is borrowed from a European language (“deek-tah-tor,” “fahn-te-zi”): the point, I take it, is that those who look to a mother tongue or a nation of origin with a longing for “home” are likely to find that empire has gotten there first, has always preceded one’s own fantasy.

“No crueler word than return,” writes Sharif in “Without Which,” one of the extraordinary long poems that conclude the book. “No greater lie.//The gates may open but to return./More gates were built inside.” Here is how that poem begins:

]]

I have long loved what one can carry.

I have long left all that can be left

behind in the burning cities and losteven loss—not cared much

or learned to. I turned and looked

and not even salt did I become.

]]

Those right square brackets recur three times per page throughout the poem’s twenty pages, sometimes separating one group of stanzas from another, as though to indicate a section break, sometimes marking an otherwise blank page. The effect is striking and disorienting: the brackets suggest the kind of editorial intervention that one sees in modern editions of ancient texts, to indicate gaps in the record, places where something now irrecoverable once stood. That they are only right brackets suggests a cordoning off of the past, a paring away of the historical self. They show us, in other words, what it looks like to have “lost//even loss.”

“Without Which” is a poem about living a life organized around the awareness of such loss. “Some days,” Sharif writes, near poem’s end, “I am almost happy having never/lived there.” Other days bring other feelings:

Would you have knocked for me?

I ask the neighbor.I have been, he said.

Then I felt his knocking

]]

inside my chest.

This is followed by a page and a half of blank space, with four instances of the doubled brackets, a replication of the knocking pulse just described, the echo of eros unfulfilled and retrospectively imagined, the sound in your head after you suddenly stop running. Desire remains, in the poem, unmet; the life that might otherwise have been recedes from view.

The book’s final poem, “An Otherwise,” weaves together lyric interiority and political demystification in a way that feels altogether new. The bones of narrative—a story of return and disappointment—are still here:

When I went

I found nothing.

It died there: desire.

All fantasy

of return.

Before arriving at that story, though, the poem begins in prose with an older history and a different figure at its center:

Downwind from a British Petroleum refinery, my mother is removing the books she was ordered to remove from the school library. Russians, mostly. Gorky’s Mother among them. The Shah is coming to tour the school. It is winter.

Here is the “relational past,” at a scale both global and familial: the Western claims to Iranian oil, the royalist anxiety about anti-capitalist influence, the persistence of the maternal figure, even in the face of attempts to expunge that figure from the record. The poet’s mother and her classmates await the Shah’s arrival and do what their teacher tells them to do: “Wave, girls, the teacher says.//My mother, waving.”

How, though, to read the mother’s wave, how to respond to its recurring gesture? On the one hand, a wave is a gesture of accommodation, not altogether unlike the noxious accommodations cataloged in “The Master’s House.” But, on the other hand, Sharif sees behind her mother’s wave a revolutionary future: in the minds of those waving girls, she writes, the Shah might have seen, had he cared to look, “rifles pointed at him.”

Early in the poem, Sharif recounts a memory of riding in her parents’ car and hearing a tape recording of “an ancient poem sung and filled/with cypresses, their upright/windscreen for what must be grown.” In Persian poetry, the cypress frequently signifies the height and grace of the beloved, but it is also associated with death and mourning. Both senses are present here. The mother and daughter who have lived these last decades in the United States share a set of memories and a longing for their source:

What did you leave behind?

We answered:A pool

linedwith evergreens,

needles fallinginto water,

its floorpainted milky

jade. . ..We wanted

to be asked

of these things.To tell of them

was to liveagain.

Here is neither the articulation of a naive desire to return home nor a self-effacing attempt to shed one’s attachment to the past. The old home is no longer there, but in its place grief—intimate knowledge of an irrecoverably lost world—survives. The ancient poem that was played during childhood car rides intertwines with a shared memory and marks, much later, a path to follow:

I began to write of cypresses.

And of small and sharp stone.

And I, on this path, a wooden handle in my palm, and a blade at the end of it.

And beyond, their windscreen, the unseen.I knew not the poem, only the weather.

I knew not the listening, only this landscape, its one clear channel.The metal in my teeth caught its frequency.

The iron shavings of my blood pulled toward this otherwise.

This is a poet discovering a new kind of power. Without knowing what it means—or where or when or even whether it exists—Sharif writes the scene she has in mind. That faith in lyric will not open the door to a lost world, but neither does it condemn the poet to Mill’s “solitary cell.” The poem becomes a place where the teenage girl whose school the Shah once visited and the daughter of that girl, the poet we now read, can meet. A place from which the world to come might be found.

An untitled poem precedes “An Otherwise.” It takes the form of a dialogue, perhaps between mother and daughter, though that isn’t specified:

Does yours have a landscape?

—Yes.

Because mine has a landscape.

—It is a path of small and sharp stone and it is lined with cypresses.

And are there other paths that you are aware of?

—One for each of us.

And are you waving?

—We will never see each other.

And are you aware of the waving?

I haven’t been able to stop thinking of this page since I first read it. Are these two voices each describing the life they might otherwise have lived? Memory puts us on solitary paths. We feel those paths pull apart in the last three lines, in which the voices don’t quite address each other. But Sharif has shown that memory isn’t merely personal, and that imagination isn’t merely fantasy. To read this book is to be made aware of the waving.

-

1

For an account that argues that oil—rather than cold war–era concern about the spread of communism—was what prompted the coup, see Ervand Abrahamian, The Coup: 1953, the CIA, and the Roots of Modern US-Iranian Relations (New Press, 2013). ↩

-

2

For a sociological account of Iranian Americans’ fraught relation to the category of whiteness, see Neda Maghbouleh, The Limits of Whiteness: Iranian Americans and the Everyday Politics of Race (Stanford University Press, 2017). Maghbouleh devotes a chapter to a discussion of how travel between the US and Iran draws out the racialized ambiguities that Iranian Americans frequently navigate. For more on the maritime context of Hughes’s poetry, see Harris Feinsod, “Vehicular Networks and the Modernist Seaways: Crane, Lorca, Novo, Hughes,” American Literary History, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Winter 2015). ↩