“Jacques Louis David: Radical Draftsman,” a superb survey of ninety drawings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, invites us to “pull back the curtain” on David’s paintings and follow the artist’s creative process through close scrutiny of his works on paper. “In a sketch the true connoisseur is able to discern the mind of a great master at work,” noted the collector and art historian Antoine Joseph Dézallier d’Argenville in 1762. “And his imagination, kindled by the beautiful flame that illuminates such a drawing, also enables him to see what is not yet given form.”

Nevertheless, by far the most spectacular David discovery—and an unexpected opportunity to witness “the mind of a great master at work”—was made recently at the Met, not through the examination of his drawings but during conservation and technical analysis of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743–1794) and Marie Anne Lavoisier (Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze, 1758–1836), a painting commissioned and executed in 1788 for which not a single preparatory drawing is known. (It is not in the current exhibition but remains on view in the Met’s galleries of European painting.) Through examination by infrared reflectography and macro X-ray fluorescence mapping, a team of curators, conservators, and conservation scientists was able to reconstitute David’s original composition, in which Marie Anne Paulze is shown wearing a large, cumbersome feather hat decorated with flowers and ribbons, while her husband is portrayed with his legs splayed out from underneath a gilt-bronze writing desk and with a red mantle draped over his shoulders. The couple was initially placed in front of shelves teeming with books and boxes, but without any scientific instruments in sight. In the finished painting, David transformed this flamboyant and cluttered composition into an elegant portrayal of the wealthy tax collector and chemist at work, assisted by his devoted spouse.1 Such distillation and paring back are consistent with David’s manner of working generally, as we learn from the three densely hung galleries in the Met exhibition.

The ambition and achievement of “Jacques Louis David: Radical Draftsman,” which is accompanied by a first-rate catalog, rests also in its serving as a concise David retrospective—albeit in black, white, brown, and gray—with dossiers devoted to almost all his major compositions (notably the great history paintings of the 1780s) and sections on his political activity during the Revolution, imprisonment after Robespierre’s downfall, rehabilitation as first painter to Emperor Napoleon, and exile in Brussels after the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. Unlike the paintings of Watteau, Chardin, Boucher, or Fragonard—all of whom have had major surveys in American museums—it is simply not possible to see those of David in any concentration outside Paris. His royal and imperial commissions—les grands formats—and his greatest portraits are of such a scale that transporting them from the Louvre is unthinkable. When in 1989 the Réunion des musées nationaux mounted a retrospective of David’s work to celebrate the bicentennial of the French Revolution, two entire floors of the Louvre’s Mollien wing were temporarily transformed into the setting for an exhibition of some 250 works (155 drawings among them).2 Even to move David’s paintings to the nearby Grand Palais, where such surveys are normally held, was not an option.

Drawing played a fundamental, if utilitarian, part in David’s creative process: it was the means by which he developed and refined the ideas given expression in his history paintings and his paintings of history in the making. As he noted in a letter of 1812, “Invention is the essential part of painting…and must be long meditated in advance…[It] involves a great many studies, drawings, and sketches.” An inveterate draftsman since childhood, David had been lucky in his tutor at the Collège de Beauvais, who had encouraged him (as he had Hubert Robert a generation earlier) to pursue his passion as an artist in spite of his family’s desire for him to enter one of the liberal professions. He initially struggled as a pupil at the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, finally winning the Prix de Rome in 1774 on his fourth attempt.

The five years between 1775 and 1780 that David spent as a pensionnaire of the French Academy in Rome proved transformative in many ways, not least because of the opportunity to immerse himself in classical antiquity. During this first residency, David copied everything he saw in sketchbooks, whose pages he reworked in pen and ink and wash and then cut and pasted onto larger sheets that he assembled in two volumes, classified by subject matter. Of the two thousand or so drawings by David that are recorded today, over half are sketches from these Roman albums. And of those thousand or more, two thirds were made after antique statuary, bas-reliefs, sarcophagi, and classical artifacts, providing a bank of images, references, and ideas upon which David relied in the arduous elaboration of his history paintings. He would continue to refer to these albums until late in his career, but they did not accompany him in exile to Brussels.3

Advertisement

In March 1826, three months after his death, the two Roman albums were taken apart by his heirs and rebound in twelve smaller volumes, considered more attractive for purchasers at David’s posthumous sale. (Not a single one sold at the time.) Of the ten albums that are known today, three are included in the first gallery of the exhibition, with pages open to show landscapes, copies after old master paintings, and copies of antique sculpture. To get a sense of how these studies migrated from album to composition, look at the reclining female figures in Roman Album No. 11, then walk over to the two preliminary sheets for The Death of Camilla, a royal commission given to David in 1781 but never completed. The supine poses of the murdered Camilla—killed by her brother, Horatius, for having grieved the death of her fiancé in public—were inspired by these copies.

Despite the centrality of drawing to his practice and his abiding dependence on the Roman albums, Philippe Bordes writes in the current catalog that David “chose to present himself only as a painter, and he no doubt had low esteem for those who adopted drawing as their principal medium of visual expression.” He did not produce autonomous drawings for collectors, drawings to be engraved, or drawings for the market generally, despite the well-established demand for compositional drawings by living artists. He rarely sold his finished drawings, preferring to make gifts of some of them to students, friends, and associates. Yet David’s most enthusiastic historian, Pierre Rosenberg, has written that of all French artists, he is almost the only one “to have imbued his drawings with an extraordinary tension, an implacable human presence, a powerful and distinct strangeness.”4

One of the great merits of the Met’s exhibition is to propose—on the walls and in the catalog—a process and sequence for the various types of David’s drawings that remained in place throughout his career, regardless of stylistic developments in the paintings themselves. For his large paintings of classical history or contemporary events—for which many preparatory drawings were made—he started with small, quickly sketched figures in black chalk. He then made groupings in a generalized architectural setting. Next he experimented with the placement and poses of the figures, at times bringing individual motifs to a considerable finish while leaving other parts of the sheet undeveloped. His nude figure studies invariably preceded the draped and clothed ones.

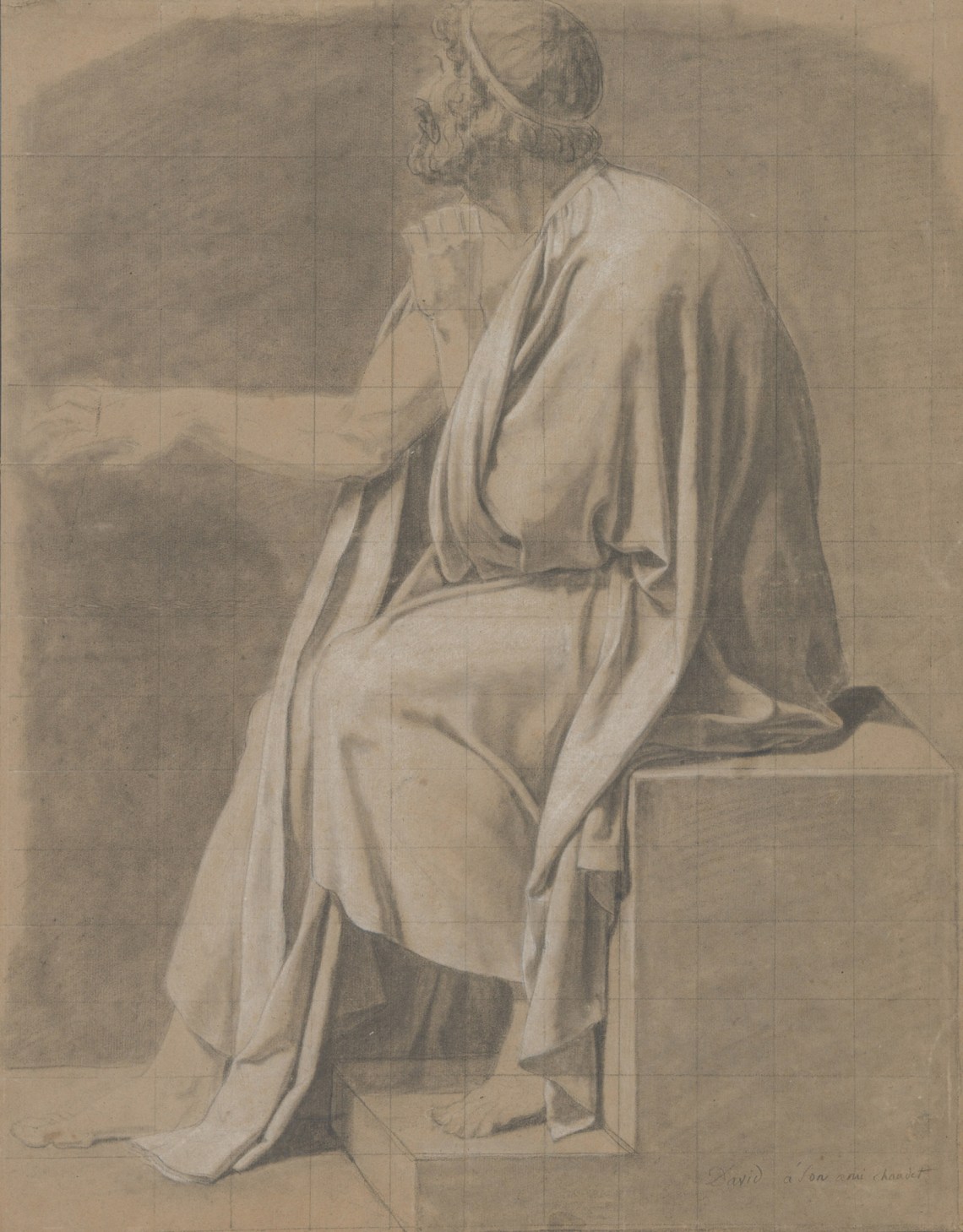

Only then did David make detailed, “finished” compositional drawings in pen and ink and wash, which were often signed and dated. These were followed by an oil sketch of modest dimensions, painted over a pen-and-ink drawing or directly onto the canvas (or panel). At this point David posed his models in the studio to make relatively large drapery studies of great refinement—there are six examples in the exhibition—which he squared for transfer to use in the final painting, the execution of which might be by more than one hand.5 He continued to work from the model as he completed his painting, on which further (significant) changes were made in the final stages. The entire process was a largely monochromatic one, with color introduced late in the sequence. Yet as his pupil Étienne Delécluze recalled David saying, with regard to the deficiencies of the French school before his appearance on the scene: “Color is the most essential quality of art, which immediately takes possession of our senses.”

Although David despised the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture and was responsible for its demise in August 1793, as a history painter he was a product of its pedagogy and a beneficiary of its patronage. His earliest drawings of the male nude, known as académies, and introduced in the first gallery at the Met under the slightly misleading rubric “A Rising Star,” are unexceptional, but once in Rome David quickly mastered the prevailing neo-Baroque manner, notably in The Combat of Diomedes, a bombastic and oversize drawing nearly seven feet in length.

Breakthrough came in Naples in 1779 with a neo-Poussinesque drawing, Belisarius Begging for Alms, and upon returning to Paris in September 1780, David was immediately identified as one of the most promising history painters of the new “youth movement” nurtured by the first painter to the king, Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre, and the superintendent of buildings, Charles Claude de Flahaut, comte d’Angiviller. David was provided with a commodious studio and lodgings in the Louvre, and despite regulations to the contrary, was permitted to apply for associate membership in the Academy on August 24, 1781, so that he could exhibit at the biennial Salon that opened the following day. He was included in the civil list for 1782 to paint a heroic subject from Roman history and given considerable latitude in both the subject and the deadline for its completion. And in May 1782 he made an advantageous marriage to Marguerite Charlotte Pécoul—sixteen years his junior—from a family of wealthy builders and architects, who brought a dowry of 50,000 livres. The signing of their marriage contract was witnessed by several dignitaries from the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, including David’s teacher Joseph Marie Vien and the first painter, Pierre.

Advertisement

As required by the Académie royale, the first painter assigned David the subject of his reception piece, which conferred full membership. Eighteen months later, on March 29, 1783, he presented an oil sketch, Andromache Mourning the Death of Hector, for the Académie royale’s approval. The finished painting was delivered just under five months later, on August 23, 1783. I belabor this procedure a little because it reminds us that, however independent, ambitious, and self-assured David was in the 1780s—as he wrote to a patron in August 1785, “No one can ever make me do anything that is to the detriment of my glory”—it was fully in his interest as a history painter to ascend the ranks of the Académie royale and benefit from the crown’s patronage.

Thus it is incorrect to state, as the catalog does, that in the early 1780s David was “casting about for subjects for his morceau de réception.” He had no choice in the matter. Of great interest, however, are several highly worked compositional drawings of heroic (and violent) ancient Roman themes that David was producing around this time, anticipating the commissions he would receive later in the decade. We know from a recently discovered list of subjects jotted down on the pages of a sketchbook around 1782–1783 that he was reading Homer, Plutarch, Racine, and other authors to find appropriate episodes from Roman history. (With Hubert Robert and Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, he was among the most learned artists of the ancien régime.) Not only did he cite passages relating to the work in progress Andromache Mourning the Death of Hector, but he also noted references to the lives of the Horatii, Septimius Severus, Caracalla, Geta, and Pompey. Between 1781 and 1783, all but the last were subjects of David’s compositional drawings.6

Although Plato’s Phaedo was not on David’s reading list at this time, in 1782 he made his first compositional drawing in black chalk, pen and ink, and gray wash for The Death of Socrates, four years before a painting of this subject was commissioned by the twenty-two-year-old Charles Louis Trudaine de Montigny. With his younger brother, Charles Michel Trudaine de La Sablière, Trudaine de Montigny was guillotined on 8 Thermidor Year II (July 26, 1794), the day before Robespierre’s removal from office. As one of the fourteen members of the Committee of General Security that oversaw the Terror, David had refused to intercede on their behalf.

The dossier around The Death of Socrates—owned since 1931 by the Met, and as such the only work whose execution can be traced in the exhibition from preliminary studies to completed painting—is among the most satisfying on view. Two patches of paper with David’s revisions affixed to the earliest compositional drawing—on the wall above the cupbearer, and for the seated figure of Crito—remind us of the unforgiving medium of pen and ink and wash, which makes the slightest alteration difficult. There was a long gestation for this composition, with David returning to it in the spring of 1786, after receiving the commission and having been encouraged to consult a scholar attached to the Oratorian Congregation on the rue Saint-Honoré regarding the appropriate treatment of the subject. (After their meeting, David made no significant changes to his composition.)

The Met’s drawing from 1786 in pen and ink, full of pentimenti and new ideas, communicates David’s excitement at being able to start work on the project again. Beautiful drapery studies for the seated Crito and the sorrowing acolyte behind the seated Plato, squared for transfer, show the rigor of his working method. In these sheets he concentrates exclusively on the folds of the men’s togas and pays scant attention to their facial expression, anatomy, or coiffure. In the absence of the painted oil sketch for The Death of Socrates—which we know that David made—we can only imagine the final refinements in accessories, color harmonies, and hues before he arrived at the finished painting.7

That these refinements were significant is demonstrated in the sequences devoted to David’s other prerevolutionary masterpieces, The Oath of the Horatii, Paris and Helen, and The Lictors Bringing Brutus the Bodies of His Sons, for which the Met was able to borrow all three painted sketches. Comparing the oil sketch to the finished work, we note that the patch of sky at the upper right will be banished from The Oath of the Horatii, all of whose protagonists will be robed in garments of different colors. In Paris and Helen muscular Paris will be relieved of most of his drapery and provided with a lyre of a different design, and the lovers’ nuptial bed will be arrayed in voluminous silks of many hues. The position of the weeping nurse at right in the oil sketch for Brutus is revised yet again in the superb drapery study from the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Tours. She now covers her face with her robes, revealing her bare neck and right arm exactly as she will be portrayed in the final painting. David’s embodiment in paint of his “taut, astricted vision” is the result of ongoing revision and distillation.8 It is achieved, as Perrin Stein notes in the catalog, “not by epiphany but by perseverance and experimentation.”

With the onset of the French Revolution, David—who attended meetings of the radical Jacobin club as early as the summer of 1790—became the “pageant master” of the new Republic. In addition to paintings and drawings commemorating the momentous early days of the Revolution and honoring its martyrs, between April 1791 and July 1794 he was responsible for organizing public festivals, planning monuments in Paris and the provinces, designing new uniforms for the holders of political office, and even producing caricatures of enemy British forces as propaganda. Although he failed to win a seat in the Legislative Assembly in September 1791, with Jean-Paul Marat’s support David was elected to the National Convention as a deputy from Paris in September of the following year. Having voted in favor of Louis XVI’s execution in January 1793, he was invited to sit on various Republican committees—including the all-powerful Committee of General Security, of which he attended over 130 meetings between September 1793 and July 1794. In June 1793 he was elected president of the Jacobins; the following month he was named secretary of the National Convention; in October 1793 he attended the interrogation of the dauphin, Louis Charles, whom he had portrayed two year earlier being instructed by his father in the lessons of the new Constitution. (The king’s commission for this double portrait, which never progressed beyond a series of preparatory drawings, caused David acute embarrassment.) Between January 5 and January 21, 1794, David held the highest political office in the land as president of the National Convention.

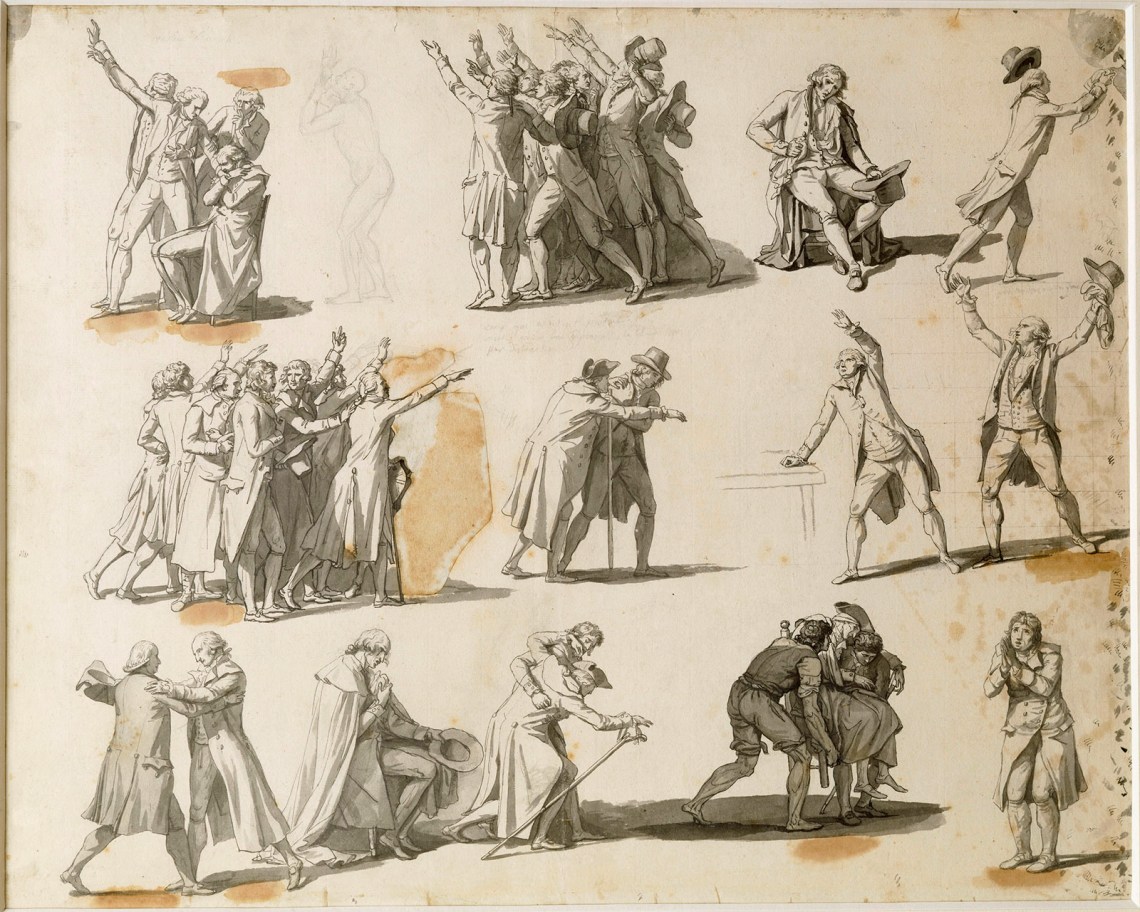

A group of superb drawings and studies in the second gallery of the exhibition bears witness to David’s frenetic activity as artist, orator, and administrator during these years. The grandest is the large drawing The Oath of the Tennis Court, completed by May 1791, and on which he may have been ruminating as early as March 1790, several months before being awarded the commission. Preparatory for a canvas intended to be twenty-two feet high by thirty-two wide (and abandoned early on), David’s drawing commemorated the event on June 20, 1789, when 630 representatives of the Third Estate, newly reconstituted as deputies of the National Assembly, found themselves locked out of their meeting place at the hôtel des Menus-Plaisirs in Versailles and repaired to the nearby indoor royal tennis court, where they swore “not to separate” and to reassemble “wherever necessary until the Constitution of the kingdom is established.”

To treat an episode of recent political history with the grandeur of history painting—and without recourse to allegory—was unprecedented in eighteenth-century France. David shows Jean Sylvain Bailly, the astronomer and mayor of Paris, standing on a makeshift table as he proclaims the oath to the assembled deputies. Hundreds of men—some fifty of whom are identifiable—raise their arms in fraternal exaltation. Edmond Louis Alexis Dubois-Crancé, who had proposed David to the Jacobins for this commission, is shown standing on a chair in the foreground at right. Robespierre, in front of him, raises his head in rapture and clutches at his chest. Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac, seated cross-legged to Bailly’s left, writes an eyewitness account of the oath-taking for his journal, Le Point du Jour. Joseph Martin d’Auch, at the far right, refusing to swear allegiance, is protected by the deputy next to him, who urges calm by raising a finger to his lips. At the far left, the infirm Michel-René Maupetit de La Mayenne is brought in on a chair supported by a muscular Parisian wearing a Phrygian bonnet.9 Placed prominently in the foreground, three ecclesiastics come together in an ecumenical embrace: the abbé Henri-Baptiste Grégoire—one of the first members of the clergy to join the Third Estate—places his hands on the shoulders of the white-robed Carthusian Dom Christophe-Antoine Gerle and the Calvinist pastor Jean Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne.

David had not, of course, been present at the royal tennis court at Versailles in June 1789, although he witnessed the civic oath taken by the deputies at the National Assembly in February 1790 and made studies in Versailles in preparation for this commission. At the lower left of the drawing he includes a racket, a basket, and some stray tennis balls, although he gives no indication that the walls of the indoor court were painted black so that players could see the ball more easily. When David exhibited The Oath of the Tennis Court at the Salon in August 1791, he noted, in a disclaimer, “The author has not intended to portray the members of the Assembly accurately.” Yet the supreme accomplishment of this drawing, as well as the related sheet of fourteen preparatory studies from the Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles—in the center of which David writes, in a note to self, “Some of those arriving may have kept their hats on inadvertently”—is not verisimilitude but conviction and authenticity. At the right edge of the Sheet of Fourteen Studies where the artist has tested his pen and brush before embarking on these prodigiously animated groups, his excitement and expectation are palpable (see illustration on page 55). These are virtuoso performances that convey nobility, affection, and optimism. It is not known whether the twenty-one-year-old William Wordsworth, who arrived in Paris at the end of November 1791, visited the Salon, which closed early the following month. (He was introduced to the Jacobins and went to the National Assembly.) But the lines in book 11 of his Prelude echo the joy and hope in David’s drawing: “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive/But to be young was very heaven!”

Unlike many of the principal figures memorialized in The Oath of the Tennis Court, David survived the Revolution’s rapidly changing political fortunes, but only just. Too ill to attend the National Convention on Sunday, 9 Thermidor Year II (July 27, 1794)—on the advice of his doctor, he absented himself for the day in order to administer an emetic—he likely avoided arrest (and death) when the deputies, in a preemptive action led by Jean-Lambert Tallien, denounced Robespierre as a tyrant and demanded his immediate execution. (With four deputies and several other officials, Robespierre was guillotined the next day.)10 In the following year, David was imprisoned twice, between September and December 1794 in the former Luxembourg Palace, and from late May to early August 1795 at the Collège de Quatre-Nations, his old school.

The third gallery of the Met’s exhibition opens, unforgettably, with six of the nine known medallion portraits in pen and ink and wash that David made during his second period of incarceration. These are terse, unsentimental, unflinching portrayals of his fellow prisoners, ex-Jacobins whose futures (like his own) are uncertain. The first in the sequence, Portrait of a Revolutionary—whose subject is still unidentified—appears unfinished. Its somewhat sketchy state is explained by an annotation on the back of the frame, which explains that it was “drawn by David, in less than twenty minutes, [with the sheet placed] on his knees.”

In the survey that follows in this room, the last thirty years of David’s career are laid out with admirable, if abbreviated, comprehensiveness. In now familiar categories, we see drawings for two monumental classical compositions, The Intervention of the Sabine Women (1799) and its companion Leonidas at Thermopylae, completed fifteen years later, which attest to David’s overarching ambitions as a history painter working on the grandest scale. Neither of these multifigured paintings was a commission. Between December 1799 and May 1805 David showed The Intervention of the Sabine Women (with a small number of other works) in a large room in the Louvre, formerly used by the Académie d’architecture. This paying exhibition, for which he charged an entrance fee of one franc, eighty centimes, may have attracted as many as 50,000 visitors.

In the meantime, David had also ingratiated himself with First Consul Bonaparte, later Emperor Napoleon. He was appointed first painter to the emperor in December 1804 after receiving a commission for a series of four enormous canvases commemorating events surrounding the coronation of Napoleon and Josephine at the cathedral of Notre-Dame (only two were completed). While David welcomed such a return to pageantry and ceremony, he was less successful than his most gifted students in satisfying the emperor’s demand for action paintings glorifying the regime’s military victories in Europe and Egypt. (Fine examples of such proto-Romantic subjects, alien to David’s sensibilities, by Anne Louis Girodet, François Gérard, and Antoine Jean Gros are on view in the Met’s companion exhibition of eighty works, “In the Orbit of Jacques Louis David: Selections from the Department of Drawings and Prints.”)

David’s late paintings of highly charged mythological subjects pared to their essentials, whose protagonists dominate the picture plane with hieratic authority, were long dismissed as the work of an artist in decline and have been rehabilitated only recently.11 It is a style burnished in exile, whose origins can be dated to the last years of his imperial service in Paris. David’s retreat from public life fostered a concentration, renewal, and refinement in his art. He wrote from Brussels in May 1817 to Baron Gros, the most loyal of his former students: “I am painting as if I were only thirty years old: I love my art the way I did when I was sixteen, and will die, my friend, with a brush in my hand.”12

These paintings still depended on the well-established (and lengthy) gestation through preliminary studies and fully resolved preparatory drawings. The knowing, carnal representation in Cupid and Psyche, on which David was at work in May 1817, had been determined four years earlier in the almost brutal compositional drawing, signed and dated 1813. Like other such sheets in David’s corpus, on first sight it might appear to have served as a modello for approval by a prospective patron or client. Cupid and Psyche was indeed a commission, from the demanding Milanese count Giovanni Battista Sommariva, a former barber’s assistant turned lawyer and politician, who had amassed a fortune in Napoleon’s service, had settled in Paris, and was forming a collection of works by the most prominent living artists. However, as was consistently the case in David’s practice, such elaborate compositional drawings functioned as a matrix for the artist himself, enabling him to proceed to the finished painting without regard for the approval of the person (or institution) for whom the work was intended.

The most intriguing section of the last gallery of the Met’s show brings together a handful of small sheets drawn in oily black chalk during the artist’s exile in Brussels. These are but a sample of the eighty or so surviving autonomous drawings of this kind, unrelated to paintings in progress, which David called “the mad things”—les folies—“that go through my mind.” Self-referential and transgressive, haunted by a primitive vision of Greek culture, with anguished warriors, veiled vestals, and sorrowing heroes, these are his “capriccios”—his croquis des caprices—Goyaesque in their strangeness, morbidity, and intensity. Despite the cornucopia of masterworks assembled in this exhibition, one left the final room regretting that so little of David’s late work could be displayed, and wanting more.

-

1

See David Pullins, Dorothy Mahon, and Silvia A. Centeno, “The Lavoisiers by David: Technical Findings on Portraiture at the Brink of Revolution,” The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 163, No. 1,422 (September 2021). ↩

-

2

See the magisterial catalog by Antoine Schnapper and Arlette Serullaz, Jacques Louis David: 1748–1825 (Paris: Editions de la Réunion des Musées nationaux, 1989). ↩

-

3

This vast repertory, a visual archaeological encyclopedia, was distinct from the sketchbooks in which David, over the course of his career, made black chalk studies for individual projects. Twenty-five were recorded in his inventory, fourteen are known today, and two are on view in the exhibition. ↩

-

4

Pierre Rosenberg and Louis Antoine Prat, Jacques-Louis David 1748–1825, Catalogue raisonné des dessins, (Milan: Leonardo Arte, 2002), Volume 1, p. 20. This two-volume catalogue raisonné has transformed Davidian studies. The year after the corpus was published, Roman Album No. 5, containing 100 drawings, reappeared. See Pierre Rosenberg and Benjamin Perronet, “Un album inédit de David,” Revue de l’Art, No. 142 (2003). ↩

-

5

Squaring preparatory drawings for transfer to a larger canvas was a well-established technique—dating at least to the Renaissance—that allowed the painter to replicate (and enlarge) an image from a drawing to the final painting. The use of a grid ensured the accurate placement of the image in the finished composition. ↩

-

6

See, in the current exhibition, The Death of Camilla, The Oath of the Horatii, Caracalla Killing His Brother Geta in the Arms of His Mother, and The Ghost of Septimius Severus Appearing to Caracalla After the Murder of His Brother Geta. ↩

-

7

In addition to the discussion in Jacques Louis David: Radical Draftsman, pp. 140–149, see the exemplary study of The Death of Socrates in Katharine Baetjer, French Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art from the Early Eighteenth Century Through the Revolution (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019), pp. 306–315. ↩

-

8

Robert L. Hebert, David, Voltaire, “Brutus,” and the French Revolution: An Essay in Art and Politics (London: Allen Lane, 1972), p. 38. ↩

-

9

This figure, un homme du peuple, has been erroneously identified as a sansculotte, a member of the group of Parisian workers who supported the Republic but had not existed as a political force in June 1789. See Richard Wrigley, “Le Serment du Jeu de Paume de Jacques-Louis David et la représentation de l’homme du peuple en 1791,” Revue de l’Art, No. 141 (2002). ↩

-

10

See David A. Bell, “The End of the Terror,” The New York Review, March 10, 2022. ↩

-

11

See Philippe Bordes, Jacques-Louis David: Empire to Exile (J. Paul Getty Museum/Clark Art Institute, 2005). ↩

-

12

Bordes, Jacques-Louis David, p. 237. ↩