There is the war, and then there is the war about the war. Vladimir Putin’s assault on Ukraine is being fought in fields and cities, in the air and at sea. It is also, however, being contested through language. Is it a war or a “special military operation”? Is it an unprovoked invasion or a human rights intervention to prevent the genocide of Russian speakers by Ukrainian Nazis? Putin’s great weakness in this linguistic struggle is the unsubtle absurdity of his claims—if he wanted his lies to be believed, he should have established some baseline of credibility. But the weakness of the West, and especially of the United States, lies in what ought to be the biggest strength of its case against Putin: the idea of war crimes. It is this concept that gives legal and moral shape to instinctive revulsion. For the sake both of basic justice and of mobilizing world opinion, it has to be sustained with absolute moral clarity.

The appalling evidence of extrajudicial executions, torture, and indiscriminate shelling of homes, apartment buildings, hospitals, and shelters that has emerged from the Kyiv suburb of Bucha and from the outskirts of Chernihiv, Kharkiv, and Sumy gives weight and urgency to the accusation that Putin is a war criminal.* By late April, the UN human rights office had received reports of more than three hundred executions of civilians. There have also been credible reports of sexual violence by Russian troops and of abductions and deportations of civilians. According to Iryna Venediktova, Ukraine’s prosecutor general, by April 21 Russia had committed more than 7,600 recorded war crimes.

Yet the US has been, for far too long, fatally ambivalent about war crimes. Its own history of moral evasiveness threatens to make the accusation that Putin and his forces have committed them systematically in Ukraine seem more like a useful weapon against an enemy than an assertion of universal principle. It also undermines the very institution that might eventually bring Putin and his subordinates to justice: the International Criminal Court (ICC).

There have long been two ways of thinking about the prosecution of war crimes. One is that it is a universal duty. Since human beings have equal rights, violations of those rights must be prosecuted regardless of the nationality or political persuasion of the perpetrators. The other is that the right to identify individuals as war criminals and punish them for their deeds is really just one of the spoils of victory. It is the winner’s prerogative—a political choice rather than a moral imperative.

Even during World War II, and in the midst of a learned discussion about what to do with the Nazi leadership after the war, the American Society of International Law heard from Charles Warren, a former US assistant attorney general and a Pulitzer Prize–winning historian of the Supreme Court, that “the right to punish [war criminals] is not a right conferred upon victorious belligerents by international law, but it flows from the fact of victory.” Warren quoted with approval another eminent American authority, James Wilford Garner, who had written that “it is simply a question of policy and expediency, to be exercised by the victorious belligerent or not.” “In other words,” Warren added, “the question is purely political and military; it should not be treated as a judicial one or as arising from international law.” As the Polish lawyer Manfred Lachs, whose Jewish family had been murdered by the Nazis, wrote in 1945, this idea that the prosecution of war crimes is “a matter of political expediency” would make international law “the servant of politics” and “a flexible instrument in the hands of politicians.”

It is hard to overstate how important it is that the war crimes that have undoubtedly been committed already in Ukraine—and the ones that are grimly certain to be inflicted on innocent people in the coming weeks and months—not be understood as “a flexible instrument in the hands of politicians.” They must not be either shaped around or held hostage by “policy and expediency.” This is a question of justice. Those who have been murdered, tortured, and raped matter as individuals, not as mere exemplars of Putin’s barbarity. The desire to prosecute their killers and abusers stems from the imperative to honor that individuality, to restore insofar as is possible the dignity that was stolen by violence.

But it is also, as it happens, a question of effectiveness. If accusations of Russian war crimes are seen to be instrumental rather than principled, they will dissolve into “whataboutism”: Yes, Putin is terrible, but what about… Instead of seeing a clean distinction between the Western democracies and Russia, much of the world will take refuge in a comfortable relativism. If war crimes are not universal violations, they are merely fingers that can point only in one direction—at whomever we happen to be in conflict with right now. And never, of course, at ourselves.

Advertisement

Even before Putin launched his invasion on February 24, the Biden administration seems to have had a plan to use Russian atrocities as a rallying cry for the democratic world. That day, The New York Times reported that “administration officials are considering how to continue the information war with Russia, highlight potential war crimes and push back on Moscow’s propaganda.” This was not necessarily cynical—Putin’s appalling record of violence against civilians in Chechnya and Syria and plain contempt for international law made it all too likely that his forces would commit such crimes in Ukraine.

But this anticipation of atrocities, and deliberation about how to make use of them, underlines the administration’s perception of the accusation of war crimes as a promising front in the ideological counterattack against Putin. As early as March 10, well before the uncovering of the atrocities at Bucha, the US ambassador to the United Nations, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, told the BBC that Russian actions in Ukraine “constitute war crimes; there are attacks on civilians that cannot be justified…in any way whatsoever.”

A week later, and still a fortnight before the first reports from Bucha, Biden was calling Putin, in unscripted remarks, a “war criminal.” At that point, he in fact seemed a little unsure about the wisdom of making the charge—initially, when asked if he would use the term, he replied “no,” before asking reporters to repeat the question and then replying in the affirmative. Significantly, Biden was responding not to ground-level assaults by Russian troops on civilians but to the shelling of Ukrainian cities. This may perhaps explain his hesitancy: civilian casualties from aerial assaults by drones, rockets, and bombs are a sore subject in recent US military history.

Having crossed the line and made this charge directly, Biden had little choice but to raise the stakes when the terrible images from Bucha were circulated. First, on April 4 he went beyond deeming Putin a criminal by calling specifically for him to face a “war crime trial.” Then on April 12 he pressed the nuclear button of atrocity accusations: genocide. “We’ll let the lawyers decide, internationally, whether or not it qualifies [as genocide], but it sure seems that way to me.” He also referred to an unfolding “genocide half a world away,” clearly meaning in Ukraine.

Biden did so even though his national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, had told a press briefing on April 4:

Based on what we have seen so far, we have seen atrocities, we have seen war crimes. We have not yet seen a level of systematic deprivation of life of the Ukrainian people to rise to the level of genocide.

Sullivan stressed that the determination that genocide had been committed required a long process of evidence-gathering. He cited the recently announced ruling by the State Department that assaults on the Rohingyas by the military in Myanmar/Burma constituted genocide. That conclusion was reached in March 2022; the atrocities were committed in 2016 and 2017. The State Department emphasized in its announcement that it followed “a rigorous factual and legal analysis.”

It is obvious that no such analysis preceded Biden’s decision to accuse Putin of genocide. When asked about genocide on April 22, a spokesperson for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights said, “No, we have not documented patterns that could amount to that.” Biden’s careless use of the term is all the more damaging because, however inadvertently, it echoes Putin’s grotesque claim that Ukraine has been committing genocide against Russian speakers in Donbas.

The problem with all of this is not that Biden is wrong but that it distracts from the ways in which he is right. This overstatement makes it far too easy for those who wish to ignore or justify what the Russians are doing to dismiss the mounting evidence of terrible crimes in Ukraine as exaggerated or as just another battleground in the information war. In appearing overanxious to inject “war criminal” into the international discourse about Putin and making it seem like a predetermined narrative, the US risked undermining the very stark evidence for that conclusion. By inflating that charge into genocide, it substituted rhetoric for rigor and effectively made it impossible for the US to endorse any negotiated settlement for Ukraine that leaves Putin in power: How can you make peace with a perpetrator of genocide? Paradoxically, it also risked the minimization of the actual atrocities: If they do not rise to the level of the ultimate evil, are they “merely” war crimes?

What makes these mistakes by Biden truly detrimental, however, is that the moral standing of the US on war crimes is already so profoundly compromised. The test for anyone insisting on the application of a set of rules is whether they apply those rules to themselves. It matters deeply to the struggle against Putin that the US face its record of having consistently failed to do this.

Advertisement

On November 19, 2005, in the Iraqi town of Haditha, members of the First Division of the US Marines massacred twenty-four Iraqi civilians, including women, children, and elderly people. After a roadside bomb killed one US soldier and badly injured two others, marines took five men from a taxi and executed them in the street. One marine sergeant, Sanick Dela Cruz, later testified that he urinated on one of the bodies. The marines then entered nearby houses and killed the occupants—nine men, three women, and seven children. Most of the victims were murdered by well-aimed shots fired at close range.

The official US press release then falsely claimed that fifteen of the civilians had been killed by the roadside bomb and that the marines and their Iraqi allies had also shot eight “insurgents” who opened fire on them. These claims were shown to be lies four months later, when Tim McGirk published an investigation in Time magazine. When McGirk initially put the evidence—both video and eyewitness testimony—to the marines, he was told, “Well, we think this is all al-Qaeda propaganda.”

This was consistent with what seems to have been a coordinated cover-up. No one in the marines’ chain of command subsequently testified that there was any reason to suspect that a war crime had occurred. Lieutenant Colonel Jeffrey Chessani, the battalion commander, was later charged with dereliction of duty for failing to properly report and investigate the incident. Those charges were dismissed. Charges against six other marines were dropped, and a seventh was acquitted. Staff Sergeant Frank Wuterich, who led the squad that perpetrated the killings, was demoted in rank to private and lost pay, but served no time in prison.

In his memoir Call Sign Chaos (2019) the former general James Mattis, who took over as commander of the First Marine Division shortly after this massacre and later served as Donald Trump’s secretary of defense, calls what happened at Haditha a “tragic incident.” It’s clear that Mattis believed that at least some of the marines had run amok:

In the chaos, they developed mental tunnel vision, and some were unable to distinguish genuine threats amid the chaos of the fight…. In the moments they had to react, several Marines had failed, or had tried but were unable, to distinguish who was a threat and who was an innocent. I concluded that several had made tragic mistakes, but others had lost their discipline…. The lack of discipline extended to higher ranks. Specifically, it was a gross oversight not to notice and critically examine a tragic event so far out of the norm. I recommended letters of censure for the division commander—a major general—and two senior colonels.

Mattis nowhere uses phrases or words like “war crime,” “massacre,” “atrocity,” or “cover-up.” He was determined, too, to exonerate the lower-ranking soldiers who participated in the violence at Haditha that day. “You did your best,” he reassured them, “to live up to the standards followed by US fighting men throughout our many wars.”

How does the “tragic incident” at Haditha differ from the murders of civilians by Russian forces in Ukraine? There are some important distinctions. Unlike in Russia now, the US had media organizations sufficiently free and independent to be able to challenge the military’s account of what happened. It had elected politicians who were willing to condemn the atrocity—in 2006, for example, Joe Biden suggested that then defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld should resign because of Haditha. Senior military commanders, including Mattis, were obviously repelled by the atrocity. Putin ostentatiously decorated the Sixty-Fourth Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade for its “mass heroism and courage” after that unit had been accused by Ukraine of committing war crimes in Bucha. There was no such official endorsement of the First Marine Division. These differences matter—false equivalence must be avoided.

Yet uncomfortable truths remain. One of the most prestigious arms of the US military carried out an atrocity in a country invaded by the US in a war of choice. No one in a position of authority did anything about it until Time reported on it. No one at any level of the chain of command, from senior leaders down to the soldiers who did the killings, was held accountable. And such minor punishments as were imposed seem to have had no deterrent effect. In March 2007 marines killed nineteen unarmed civilians and wounded fifty near Jalalabad, in Afghanistan, in an incident that, as The New York Times reported at the time, “bore some striking similarities to the Haditha killings.” Again, none of the marines involved or their commanders received any serious punishment.

Perhaps most importantly, nothing that happened in these or other atrocities in Iraq or Afghanistan changed the way that deliberate acts of violence against foreign civilians are presented in official American discourse. The enemy commits war crimes and lies about them. We have “tragic incidents,” “tragic mistakes,” and, at the very worst, a loss of discipline. When bad things are done by American armed forces, they are entirely untypical and momentary responses to the terrible stresses of war. The conditioning that helps make them possible, the deep-seated instinct to cover them up, and the repeated failure to bring perpetrators to justice are not to be understood as systemic problems. Nowhere is American exceptionalism more evident or more troubling than in this compartmentalizing of military atrocities.

The only way to end this kind of double standard is to have a single, supranational criminal court to bring to justice those who violate the laws of war—whoever they are and whatever their alleged motives. This idea has been around since 1872, when it was proposed by Gustave Moynier, one of the founders of the International Committee of the Red Cross. It seemed finally to be taking shape in the aftermath of World War II and the Holocaust, when a statute for an international criminal court was drafted by a committee of the General Assembly of the UN. This effort was, however, stymied by the USSR and its allies. In the 1990s the combination of the end of the cold war and the hideous atrocities committed during the breakup of Yugoslavia and in Rwanda gave the proposal a renewed impetus. This led to the conference in Rome in June and July 1998, attended by 160 states and dozens of nongovernmental organizations, that finally adopted the charter for the ICC. This statute entered into force in July 2002, and the ICC began to function the following year.

Of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, one (China) opposed the adoption of the ICC’s statute. Two (the United Kingdom and France) supported it and fully accepted its jurisdiction. That leaves two countries that ended up in precisely the same contradictory position: Russia and the US. Both signed the Rome statute—Russia in September 2000, the US three months later. And both then failed to ratify it. Putin, presumably because of international condemnation of war crimes being committed under his leadership in Chechnya, declined to submit it to the Duma in Moscow. George W. Bush effectively withdrew from the ICC in May 2002, following the US-led invasion of Afghanistan and his declaration that “our war against terror is only beginning.”

The US then began what Yves Beigbeder, an international lawyer who had served at the Nuremberg Trial in 1946, called “a virulent, worldwide campaign aimed at destroying the legitimacy of the Court, on the grounds of protecting US sovereignty and US nationals.” Against the backdrop of the “war on terror,” Congress approved the American Service-Members’ Protection Act (ASPA) of 2002, designed to insulate US military personnel (including private contractors) from ICC jurisdiction. The ASPA placed numerous restrictions on US interaction with the ICC, including the prohibition of military assistance to countries cooperating with the court. Also in 2002, the US sought (unsuccessfully) a UN Security Council resolution to permanently insulate all US troops and officials involved in UN missions from ICC jurisdiction. In late 2004 Congress approved the Nethercutt Amendment, prohibiting assistance funds, with limited exceptions, to any country that is a party to the Rome statute.

These attacks on the ICC culminated on September 2, 2020, when the Trump administration imposed sweeping sanctions on Fatou Bensouda, a former minister of justice in Gambia, who was then the ICC’s chief prosecutor, and Phakiso Mochochoko, a lawyer and diplomat from Lesotho, who heads a division of the court. The US acted under an executive order that declared their activities a “national emergency.” The emergency was “the ICC’s efforts to investigate US personnel.” Trump’s secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, denounced the ICC as “a thoroughly broken and corrupted institution.”

A year ago, the Biden administration lifted these sanctions against Bensouda and Mochochoko, saying they were “inappropriate and ineffective.” But the US did not soften its underlying stance, which is that, as Biden’s secretary of state, Antony Blinken, put it,

we continue to disagree strongly with the ICC’s actions relating to the Afghanistan and Palestinian situations. We maintain our longstanding objection to the Court’s efforts to assert jurisdiction over personnel of non-States Parties such as the United States and Israel.

In principle, this hostility to the ICC is rooted in the objection that the court is engaged in an intolerable effort to bind the US to a treaty it has not ratified—in effect, to subject the US to laws to which it has not consented. If this were true, it would indeed be an unacceptable and arbitrary state of affairs. But this alleged concern is groundless. The ICC does not claim any jurisdiction over states—it seeks to prosecute individuals.

This distinction was vital to the Nuremberg Tribunal, which stressed that “crimes against international law are committed by men, not by abstract entities, and only by punishing individuals who commit such crimes can the provisions of international law be enforced.” Moreover, the US is already a party to the treaties that define the crimes the ICC is empowered to prosecute. The ICC follows the precedents and practices of international criminal tribunals that the US enthusiastically supported and participated in: the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials after World War II, and the courts established in the 1990s to prosecute those responsible for atrocities in Yugoslavia and Rwanda. If the ICC is illegitimate, so were those courts.

The brutal truth is that the US abandoned its commitment to the ICC not for reasons of legal principle but from the same motive that animated Putin. It was engaged in aggressive wars and did not want to risk the possibility that any of its military or political leaders would be prosecuted for crimes that might be committed in the course of fighting them. That expediency rather than principle was guiding US attitudes became completely clear in 2005. The US decided not to block a Security Council resolution referring atrocities in the Darfur region of Sudan to the ICC prosecutor. (It abstained on the motion.) It subsequently supported the prosecution at the ICC of Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir and the use by the Special Court of Sierra Leone of the ICC facilities in The Hague to try former Liberian president Charles Taylor for crimes committed in Sierra Leone.

This American support was welcome, but it has been almost as damaging to the ICC as the outright hostility of the US had been. It suggested that in the eyes of the US, the only real war crimes were those committed by Africans. To date, the thirty or so cases taken before the ICC all involve individuals from Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Libya, Mali, or Uganda. This selectivity led the African Union to label the ICC a “neo-colonial court” and urged its members to withdraw their cooperation from its prosecutions. However false the charge, it is easy to see how credible it might seem when the US has alternately endorsed the legitimacy of the ICC in prosecuting Africans and called the same court corrupt and out of control when it explores the possibility of investigating war crimes committed by Americans.

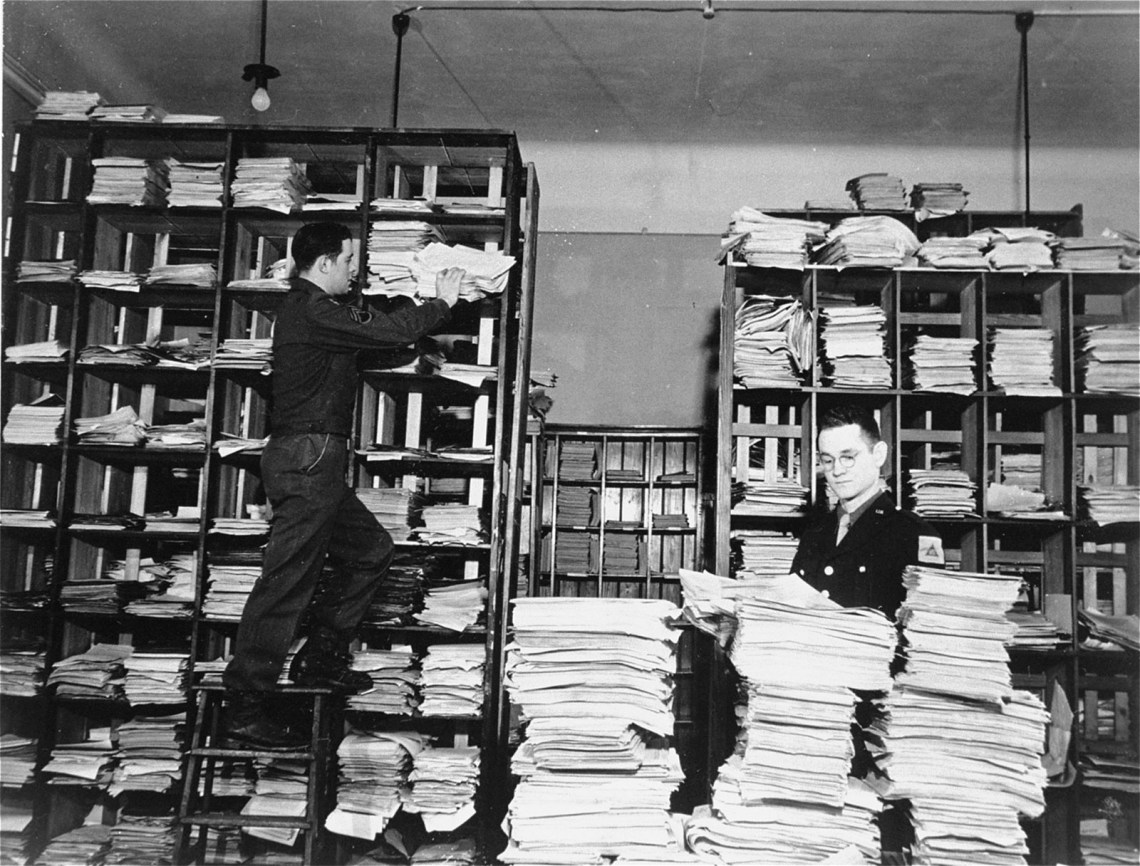

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, more than forty member states of the ICC, most of them European but also including Japan, Chile, Colombia, and Costa Rica, formally asked the court “to investigate any acts of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide alleged to have occurred on the territory of Ukraine from 21 November 2013 onwards.” The ICC prosecutor Karim Khan has begun to do this. Crucially, though Ukraine is not itself a party to the ICC, it had already accepted the court’s jurisdiction in relation to war crimes on its territory, first in 2014 and again in 2015, the second time “for an indefinite duration.”

It is Ukraine’s choice that the ICC be the body that investigates and prosecutes Russian atrocities against its people. This means that if there is to be any prospect of bringing Putin and his accomplices to justice for murder, rape, and torture, it must lie with the ICC. The “war crime trial” that Biden called for on April 4, if it were ever to be possible, could be conducted only at The Hague.

The Biden administration knows this very well. On April 11 Charlie Savage reported in The New York Times that officials are “vigorously debating how much the United States can or should assist an investigation into Russian atrocities in Ukraine by the International Criminal Court.” But the administration is simultaneously spreading a fog of vagueness over this very question. In his April 4 press briefing Jake Sullivan, the national security adviser, said, “Obviously, the ICC is one venue where war crimes have been tried in the past, but there have been other examples in other conflicts of other mechanisms being set up.” He promised that “the appropriate venue for accountability” would be decided “in consultation with allies and with partners around the world.” Yet all of those significant allies are members of the ICC, and the most important of them, Ukraine, has specifically given the court the job of trying to bring the perpetrators to justice.

Why continue to avoid this obvious truth? A yawning gap has opened between Biden’s grandiloquent rhetoric about Putin’s criminality on the one side and the deep reluctance of the US to lend its weight to the institution created by the international community to prosecute such transgressions of moral and legal order. It is a chasm in which all kinds of relativism and equivocation can lodge and grow. The longer the US practices evasion and prevarication, the easier it is for Putin to dismiss Western outrage as theatrical and hypocritical, and the more inclined other countries will be to cynicism.

It has been said repeatedly since February 24 that if the democracies are to defeat Putin, they must be prepared to sacrifice some of their comforts. Germany, for example, has to give up Russian natural gas. What the US must give up is the comfort of its exceptionalism on the question of war crimes. It cannot differentiate itself sufficiently from Putin’s tyranny until it accepts without reservation that the standards it applies to him also apply to itself. The way to do that is to join the ICC.

—April 28, 2022

This Issue

May 26, 2022

The Russian Terror

Beyond the Betrayal

-

*

For more on the atrocities in Ukraine, see Tim Judah’s “The Russian Terror” in this issue. ↩