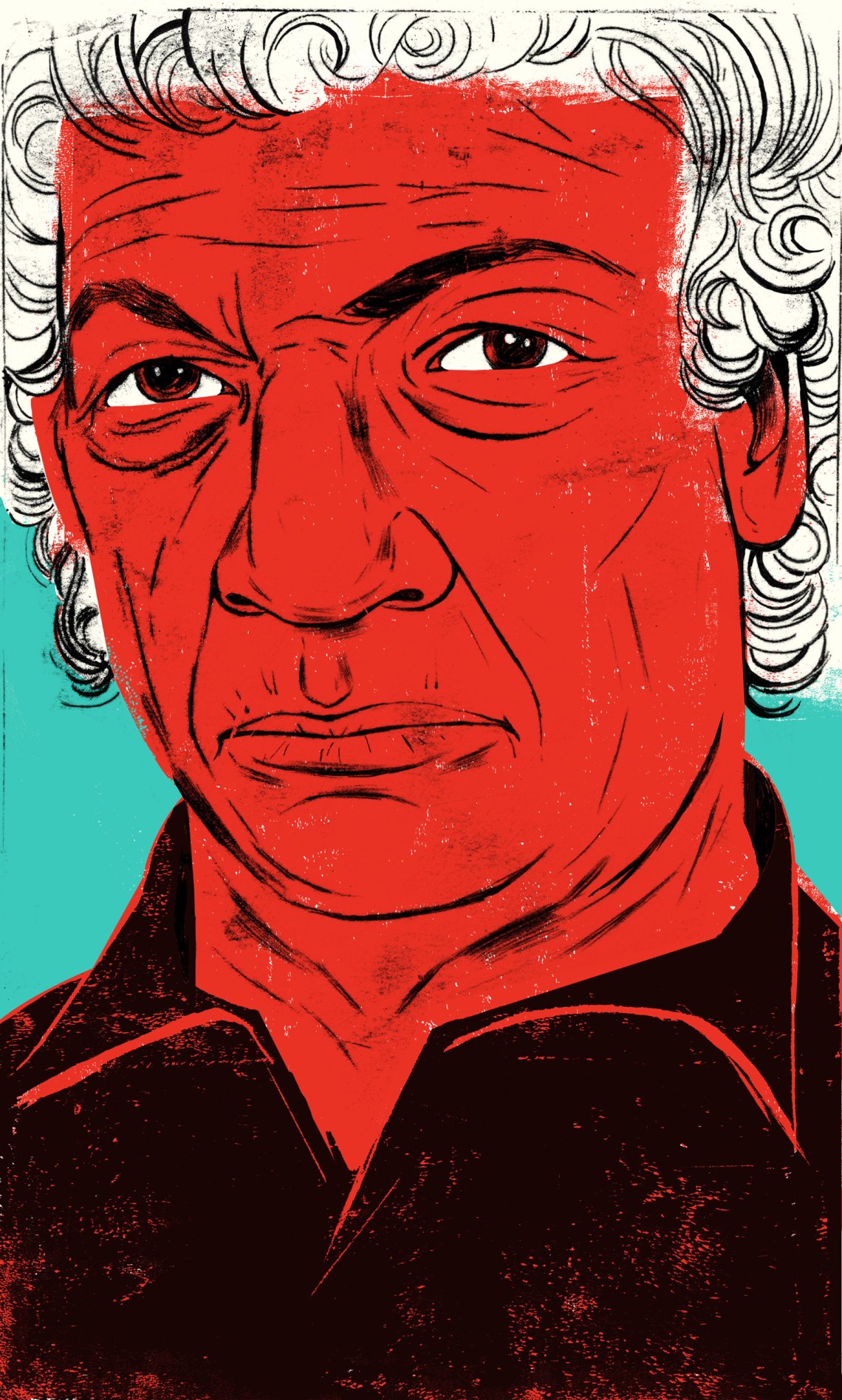

Some way through Francisco Goldman’s Monkey Boy, the novel’s narrator—an accomplished writer in middle age called Francisco Goldberg, whose name isn’t his only resemblance to the author—recalls “the day I became a journalist.” As an aspiring writer of fiction in his early twenties, he left New York for his mother’s homeland in Central America, intending to hole up in a house her family owned there and hone his craft. But the year was 1979. The country was Guatemala. And those two facts—as students of cold war history know now but most Americans were scarcely aware of then—meant that young Francisco wasn’t arriving in a bucolic backwater. He was plunging into what was fast becoming one of the era’s darkest proxy wars, a horrific conflict that was first sparked in the 1950s by the United States’ covert removal of Guatemala’s left-wing president, Jacobo Árbenz, and that over the ensuing decades claimed the lives of 200,000 people, displaced a million more, and unleashed the guns and gangs that rule the country now.

The cottage by a lake to which the young writer hoped to repair, it turns out, is off-limits: the area is rife with guerrilla activity and the military’s wanton repression. Young Francisco, stuck in Guatemala City, stuffs short stories set back home into envelopes addressed to prospective publishers and MFA programs in the US. The violence worsens. Devastating the countryside’s indigenous peoples, it also spits so many maimed victims onto the capital’s streets that on some days, a medical student with whom Francisco is friendly tells him, their corpses have “to be stacked like firewood” in the city’s morgue. One day she sneaks him in to see:

There weren’t bodies stacked like firewood that day, but there were corpses laid out on three of the concrete autopsy tables. The cement floor had a wet sheen, as if just hosed…. On the autopsy table closest to us lay the corpse of a young man with a trimly muscular body, a handsome face with Amerindian features, eyes serenely closed, skin youthfully toned and damp, a black mustache, soft-looking instead of bristly, and wisps of chin hair. His torso and arms were speckled with brownish dots…cigarette burns. What looked like a popped blister, circular and pink, was where his penis should have been.

What’s striking about Francisco’s recollection of the experience, though, is how it changed what he wanted to write. This was the day he became a journalist, he explains, not because seeing this murdered young man sent him down a rabbit hole of ready questions—who was he, who had done this to him, and why?—but for other reasons that had to do, at bottom, with himself:

Probably all of Guatemala knew who was doing that, to young men and women especially, and why. Then what difference could it make to see it for yourself? Because to witness something like that implicates you, it allows that reality to go on living inside you, growing darker, more impenetrable, unless you accept the challenge of living with it and trying to make it clearer instead of ever darker and more confusing.

These lines, appearing as they do in a book by Francisco Goldman, can’t but make one think of his work as an investigative reporter who has produced vital chronicles of some of this hemisphere’s worst atrocities (including a brave inquest into the 1998 murder of Bishop Juan Gerardi, the leading investigator of human rights abuses during the Guatemalan civil war*). But Goldman, like his alter ego in Monkey Boy, is a writer whose career began when he received the thrilling news that Esquire wanted to buy two of those stories he had submitted by airmail from Guatemala City—and when an editor there also wondered, intrigued by the talented young man with that return address, if he might like to write a reported piece about what he was seeing.

Goldman has toggled ever since between the divergent but linked demands of imaginative fiction and investigative reporting, and he has increasingly come to operate in the fruitful murk between them. Monkey Boy is a book whose narrator shares its author’s biography and whose cover has a photo of him in his awkward youth, staring out from under the title that is the nickname he was given, as a big-eared Jew with a funny name and olive skin, by the cruel kids with whom he grew up in a working-class suburb of Boston. It’s clear that we are to take the voice and memories of this book’s narrator as its author’s, and though Goldman’s experience as a journalist is vital to his backstory here, his focus in Monkey Boy predates that day in the morgue. It involves other realities, dark and confusing, that go back to the people who were closest to him in his boyhood and that have remained crucial to the mature writer, and thus the novelist, he would become.

Advertisement

Francisco Goldman was born in Boston to a Guatemalan mother and a Jewish father whose parents were from Ukraine and whose abusive treatment of his family, recounted in scary detail in Monkey Boy, goes some way to explaining why “Frankie,” as he became known in the Anglo world of his youth, fled home as soon as he could. His first reported piece for Esquire led to a decade covering Central America’s wars, which also gave him the material for his first novel, The Long Night of White Chickens (1992), whose narrator’s mother is a guatemalteca much like his own, and whose plot stretched from Massachusetts to Mesoamerica and back again. Two ensuing novels spanned similar geographies but drew less from his own life than from history and the news. The Ordinary Seaman (1998) is the tale of a Nicaraguan veteran of Central America’s wars who finds himself, with fourteen fellow marineros, trapped on a freighter off Brooklyn that’s been abandoned by its owner. The Divine Husband (2004) conjures the life and loves of José Martí, the nineteenth-century Cuban statesman, polymath, and poet whose migrations involved stints in both Guatemala and New York. Then came The Art of Political Murder and a personal tragedy that would be the subject of Goldman’s next book.

On a beach vacation in Oaxaca in 2007, Goldman and his beloved young wife, the writer Aura Estrada, were playing in the waves when she had a freak accident and broke her neck. Goldman’s grief at Estrada’s death left him, by his own account, suicidal. But he wrote a heartbreaking memoir of their love and her death that—because he felt the need to modify certain scenes and craft dialogue from Estrada’s journals in order to convey, as he put it, the “emotional truth” of what happened—he published as a novel, Say Her Name (2011). It was notable, in Goldman’s oeuvre, for the raw immediacy of its prose composed in grief. (He has since published another book of nonfiction, 2014’s The Interior Circuit: A Mexico City Chronicle, and much reporting on the unexplained deaths of young people in Mexico, where he now lives.) But Say Her Name also seems to have given him a mode of “self-writing” that he has found useful for reckoning not merely with recent traumas but with aspects of his deeper past that may explain why, for example, he wasn’t able to have a relationship of real loving depth until he met Estrada, not long before he was fifty.

“Autofiction” has in recent years become a popular term for novels whose writer-narrators share much with their authors. Books by Ben Lerner and Rachel Cusk, among others, have also prompted confusion among readers and critics who wonder what exactly this vague label describes if not authors’ melding, in ways that are as old as authorship, of real scenes from their lives with a frame they make up. The critic Christian Lorentzen has suggested that the autofiction label is best used to describe works in which “the book’s creation is inscribed in the book itself,” and Monkey Boy certainly qualifies. It’s a book about, and also by, a writer journeying across space but also back in time, at least in his mind, to the places that made him.

Francisco Goldberg’s dusky trek across New England in winter begins in the dingy men’s room at New York’s Penn Station, where, he recalls, Louis Kahn died of a heart attack. We get the sense, from the writer’s musings on the great architect’s sad end and the soppressata hero he grabs from his go-to salumeria on Eighth Avenue for his train ride to Boston, that he’s familiar with this itinerary. Goldberg is going to visit his mother in her nursing home and give an interview on public radio about a Guatemalan general who had a bishop murdered there and hates Goldberg’s guts. His memories of the sad town where he grew up “amid rocky field and cold forest” will animate this journey; he woke up in Brooklyn thinking about the sounds his father, Bert, made when he rose at dawn, in the writer’s boyhood home, before rumbling off in his Oldsmobile to his job crafting porcelain dentures for the Potashnik Tooth Company in Cambridge. Being reminded of the man whose anger defined his boyhood, “feeling like his shadow is falling across the decades,” doesn’t augur well for the trip ahead.

The train leaves the city’s sprawl and enters Connecticut. On the seat next to him, Goldberg has his sandwich and a novel by Muriel Spark. But there’s nothing like gazing from a moving train or, here, contemplating “the ruin and splendor of Bridgeport,” for turning one’s mind to where one’s been. As the train rolls from New Haven to the gray seascape of Mystic, he recounts parts of his past that will fill the encounters of his weekend with meaning: dining with a girl he adored in tenth grade, now a prosperous lawyer in Boston; sitting with his “Mamita” in her nursing home as she giggles in dementia’s face; meeting with another guatemalteca who spent years in their house as a kind of au pair, and who knows things about the sources of Mamita’s sadness and Bert’s rage their son never did. He recalls a motel where his father brought the family (“Was that motel around here, in Mystic? Falmouth? Woods Hole?”), from whose balcony he looked down “into the pool where Mamita was swimming laps in a light-blue bathing suit, her hair tucked under a bathing cap.”

Advertisement

Most of the memories, though, that ramify through this landscape and have echoed through his life are darker—the first time Bert, enraged by his ten-year-old son raiding his coin collection to buy Matchbox cars, hit him; his mother’s chirped protests during all the beatings that followed (“Bert! Not in the head!”); his uncanny ability, as a young reporter, to “flatten out” in dangerous situations, which he now attributes to the ways he trained himself, as a boy, to weather the fists of a father who was a kind mentor to several kids in their neighborhood but couldn’t stand his own.

There are also memories, from later, of women loved and lost, and hopeful thoughts of the future. At forty-nine, Goldberg may be “the sort of self-sufficient man people think must not really require or especially want anyone to be close to.” The writer has his books, after all, “and an eventful past to ruminate on, just look at him, invited on the radio to talk about his enemy General Cara de Culo.” But he’s ready to try again. Or so he imagines as he sends the cute Mexican woman he’s recently met in Brooklyn hopefully-funny text messages about pelicans and bike rides, and he checks his phone at anxious intervals throughout the weekend to see if she’s replied.

The train crosses into Massachusetts. He ponders its bygone Amerindian sachems and remembers Proust describing how “a man, during the second half of his life, might become the reverse of who he was in the first.” Finally he reaches Boston’s South Station. His feet lead him from the station’s doors, as he says they always do here, to a restored eighteenth-century brig in the harbor nearby. In high school he had a job there teaching tourists about the Boston Tea Party; the vessel holds another telling memory, too. After his first novel came out, he’d returned to the city on a book tour and was contacted by a reporter from The Boston Globe. Thinking the reporter wanted to profile him, he proposed meeting by this boat where it all began. But the reporter, when he arrived, was glum: “We received a fax at the newspaper that makes a serious allegation.” The woman who’d sent it, having read the Globe’s review of his novel, was an old classmate from high school: “Lana Gatto alleges that you are not a Hispanic, err, or a Latino. She says that in high school your name was Frank and that you’re Jewish.”

The bemused writer’s riposte to this nonsense was sharp: “I admit it. I am Jewish, and all these years I’ve been hiding my true identity behind the last name Goldberg.” The reporter skulked off. But the problem captured in his queries (which also find the writer patiently explaining why he didn’t go around Boston suburbs in the 1970s waving a Guatemalan flag and insisting on being called “Francisco”) persists. The Irish and Italian kids with whom he grew up, having embraced a white identity their forebears couldn’t, policed its edges fiercely. Young Frank’s first joyous experience of making out with a girl turned into the deep hurt of showing up at school to find everyone repeating a rumor that she’d said kissing Monkey Boy was like being chewed by an ape.

Little wonder that he was unable to try to kiss anyone for years afterward—or that his first “reunion” with anyone from high school is the dinner, on his first night in Boston, with a girl from back then with whom he’s happily able to recall shared traumas and express tender memories. As his consciousness moves backward and forward in time, he remains tied to Boston Common in March, with its frozen grass and air of “everything tired of being dead.” And he remains tied, too, to the quest that will find him, the next afternoon, bringing a tin of his mother’s favorite butter cookies to the Green Meadows retirement home out by Route 128, where she’s concluding her life a long way from where it began. He makes her laugh by asking her, as he does every time he visits, “Ay, Mamita, how did a niña bien from the tropics like you ever end up in a joint like this?”

The answer reaches back to her ambitious parents in Guatemala City, who helped run a thriving toy store and enrolled her in the city’s Colegio Inglés Americano, before sending her and her brother to college in California; to Boston, where in the 1950s she landed in a Catholic boardinghouse after her mother determined that she wouldn’t marry any of her pie-eyed suitors back home, and where she worked as a bilingual secretary for the Guatemalan consul; to her brief ensuing stint, before she found a career teaching Spanish at the Berklee School of Music, in the employ of a denture company whose technicians included an athletic Jew who told her tales of his own immigrant past at Boston’s best restaurants, while they were courting, before he moved her, after they wed, to the lonely suburb where she’d remain.

Some of this the writer learns from eighty-year-old Mamita, who’s more willing, as her memory dies, to mine its contents for her Frankie. He knows more from his sister and from his uncle. Over the weekend, he learns more still from one of the au pairs who lived in the room Bert built in their house’s basement, and who tell him over coffee about how many times “Yoli” packed her bags and tried to leave, only to be scared at the last minute into staying; about how after she had brought her young son home to “Guate” it was her devout Catholic mother, his Abuelita, who insisted she return to Boston when little Frankie came down with tuberculosis; and about how the true source of Bert’s rage, when she returned and he began abusing her, was his impotence.

To the people with whom Francisco grew up, the Latino side of his heritage toward which he would gravitate was even more confounding than his Jewishness. But he’s often wondered, he admits, why as a young author he didn’t just adopt his mother’s surname (who wants to be “another Jewish writer”?) to avoid confusing the philistines, as common in publishing as they are in life, who want us all to be “just one thing.” It was only through reading other Jewish writers who were steeped in Catholic mores, he says, that he learned to embrace what Natalia Ginzburg called her pathos ebraico—a fortifying sense of his Jewishness, alongside the other parts of himself, as feeding his outsider’s sense for always seeing how no one is “just one thing.”

He shares with his mother an old photo he got from a distant cousin in Guatemala, which attests that her own criollo clan isn’t as white as “good families” in that part of the world all pretend: it depicts her mustached grandfather and his wife from the country’s coastal lowlands, who’s plainly of African descent. Mamita giggles in her wheelchair. She giggles louder when Frankie asks her if it’s true that, back when her only escape from Bert’s house was the readings and talks she attended at the Latin American Society in Boston, she’d met a man there. She takes another cookie. “Yes, I did.” Miguel was from Mexico City and worked for Honeywell, which sent him to Boston to learn about computers. He had long hair and liked to read, and she loved him. They’d spent a few months, before he went home, meeting at the Hilltop Sheraton. “I’m proud of you, Mami,” says her son. “That you were brave enough to do that, to have your love affair.”

Frankie and his father eventually found, before Bert’s death, a kind of equilibrium, if not love, in a relationship that “was a failure in pretty much every way.” It’s to the writer’s great relief that he hasn’t become his father in the way he treats his intimates. But he also wonders at how, in certain ways, he has become his mother—an immigrant whose life has spanned two cultures and countries and who perhaps found, after years had passed, that she never felt at home in the United States but no longer fit in her homeland either. “One of the strangest things I’ve done with my own life,” he reflects, “has been to follow her path, in a sense willfully divesting in order to pour myself into that mold of divided.”

On his last night in town, after shutting down the hotel bar, he finds his weekend’s denouement on a late-night walk down darkened streets. Through the glowing window of a brownstone in Back Bay, the writer glimpses a painting that prompts him to conjure a scene that’s drawn not from memory but from his whiskey-warmed imagination. It involves his young mother having her portrait painted, in a townhouse like this one, by a war-hero friend of her new husband’s. The sequence’s dreamlike leaps, in a narrative whose revelations have up to now felt finely measured, threaten to lose the reader. It’s almost as if the creator of this narrator who’s convinced us that the events he’s recounted all occurred during one weekend rather than over several visits, as perhaps seems more likely, wants to remind us that we’re reading a work of fiction whose author’s name isn’t Goldberg but Goldman. But this is the prerogative of a novelist. And it may be the imperative of this one, who is both the son of a society “that somehow collectively realized there was a certain kind of truthfulness it was essential to do without” and a writer who, as Goldman once told an interviewer, has “never liked the memoir form because I tend to think that memory fictionalizes anyway.”

Either way, the memoir-as-novel Goldman has written about the people who made him breathes with expiation. It’s an unloading of truths that no longer feel heavy, in a life that has landed, as this book’s end suggests, in a good place: his crush texts him back.

Today Goldman has a new partner and a young daughter. He’s beloved by a generation of younger writers who have built careers based on his conception of America as composed of the essential bonds, often violent, that join the United States to the lands and peoples to our south. As a member of that generation who’s also a half Jew from New England, I share even more with Goldman than his sense of “American” as a word that connotes not one country but a hemisphere. And reading this painful, refractive, beautiful book, I couldn’t but be reminded of when I met him for the first time, a few months after his beloved Aura’s death, when he was still raw with grief. He had come to Berkeley to discuss The Art of Political Murder. When he said then through watery eyes that if the murderers he’d fingered in that book wanted him dead, he was ready to die, I believed him. He’s not ready now.

-

*

The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed the Bishop? (Grove, 2007); reviewed in these pages by Aryeh Neier, November 22, 2007. ↩