Before Hitler and Stalin (and Putin), there was Maximilien Robespierre, the leader of the French Revolution during the period in 1793–1794 known as the Terror. If Napoleon Bonaparte had not come to power and made war on much of Europe between 1799 and 1815, Robespierre would have been the most controversial figure of his time. Yet he did not rule for long, did not govern alone, and began his political career as a staunch proponent of liberal democracy: he argued against slavery, the death penalty, and poll taxes; favored freedom of religion and the press; and opposed France’s rush to declare war on Austria in 1792. Known to his followers as “the Incorruptible” because he disdained those who profited from the circumstances of revolution and war, he nonetheless became the face of all that was most repugnant in the French Revolution.

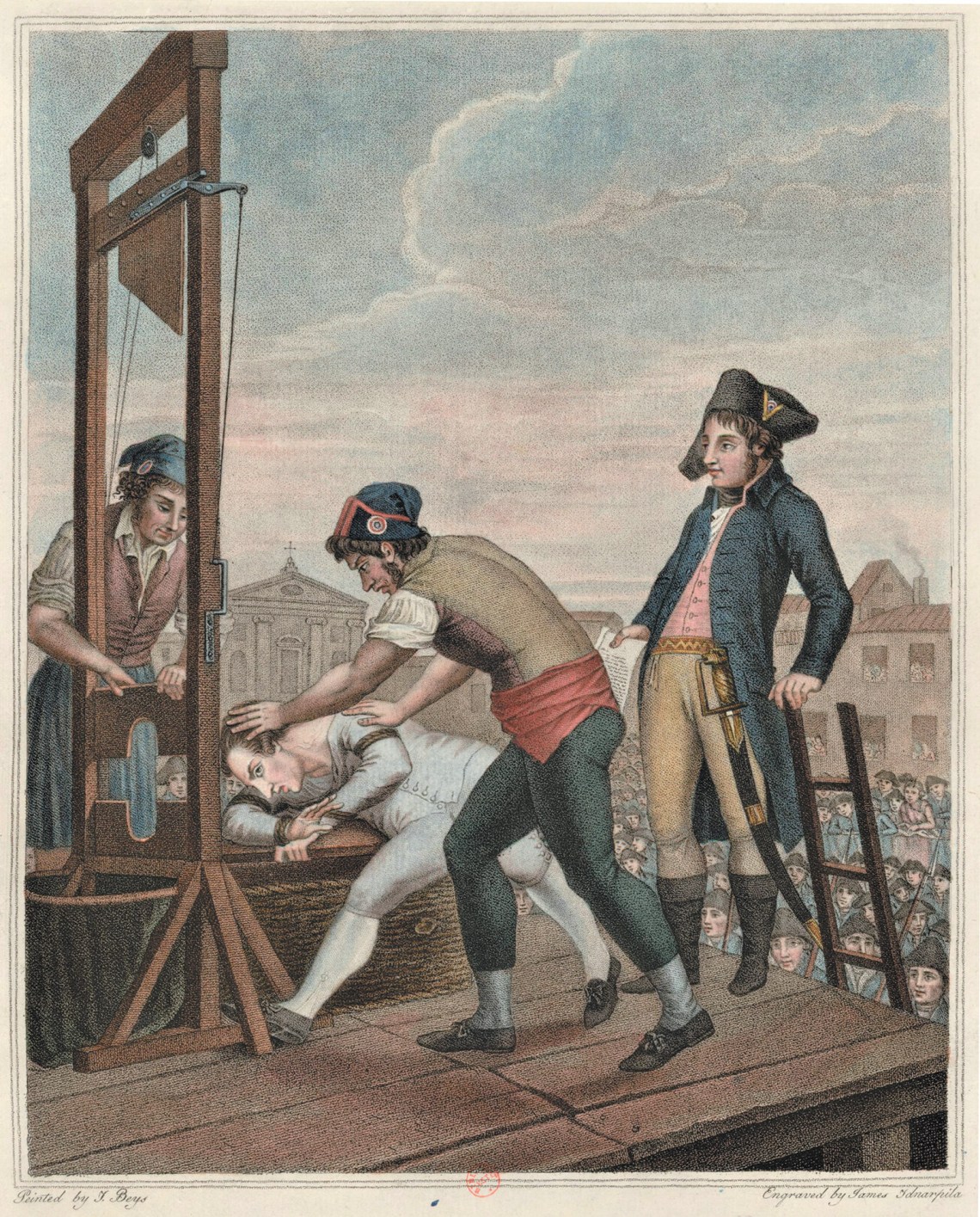

Was he just a scapegoat, the sacrificial victim who could be blamed in retrospect for the Terror—for the many thousands who were executed and the hundreds of thousands imprisoned as suspects, for the muzzling of the press and the repression of all dissent? Robespierre fell from power on July 27, 1794, when his fellow deputies in the National Convention, the legislature that governed France from 1792 to 1795, ordered his arrest. Declared an outlaw after his supporters got him released from custody, he was recaptured and guillotined the next day. His fall set in motion a startling change of direction, much to the surprise of those who had brought him down. They had intended only to rid themselves of a political enemy who seemed poised to act against them. Their leaders included some who had undertaken brutal purges of their own in the provinces, rivals further to Robespierre’s left on the Committee of Public Safety, which ran the government, and deputies who feared for one reason or another that they would be next on the list of those declared traitors.

The deed once done, they tried at first to portray it as a victory for the people of Paris and the deputies over a determined tyrant and his small band of followers. But the repercussions could not be contained, and almost immediately the most objectionable policies were dismantled. The draconian law of June 10, 1794, limiting the rights of defendants and broadening the definition of “suspects” was repealed; in addition to the usual “enemies of the people,” it had included those who “sought to inspire discouragement,” those who “disseminated false news,” and those who sought “to undermine the energy and the purity of revolutionary and republican principles.”

The chief prosecutor of the revolutionary court was tried and executed. Some of those who had conspired to remove Robespierre faced detention in their turn, while suspects in Parisian prisons found themselves free again. The Convention curbed the powers of the Committee of Public Safety, and when the cascade of changes further emboldened those who opposed the repressive policies, the deputies closed the Jacobin Club, which had been the political base for so many of them during five tumultuous years.

As part of the effort to move forward, the deputies needed to construct a convincing narrative about the events of the previous year. Since it was impossible to blame Robespierre for everything—his only claim to institutional power was membership on the twelve-man Committee of Public Safety—they had to dig deep in order to portray him as the chief architect of the regime of terror. The official report on him and his “accomplices” claimed that though Robespierre was “timid and fearful,” “he wanted to drive men to tyranny” by pushing for social leveling; denouncing merchants, property owners, and the rich in general; undermining discipline in the armies through the dissemination of radical newspapers to soldiers; setting up an elaborate network of domestic spies to report on any possible dissent; and accusing of “moderationism” anyone who opposed the mass indiscriminate executions. Perfidy followed from Robespierre’s character, according to the report: his desire for domination, corrosive envy of his rivals, personal lack of talent and hatred therefore of those with any merit, vindictive pride, and dislike of any celebrity other than his own.

In order to make sense of Robespierre’s supposed ascendancy, the report also had to lay out the litany of praises found in the letters sent by individuals and popular clubs to their “idol,” “their new god, Maximilien.” The report’s author laments having seen “everywhere, the same prostitution of incense, best wishes, and homages” in encomiums such as “the contribution of his rare talents,” “the incorruptible,” “the virtuous” Robespierre “who covers the cradle of the Republic with the aegis of his eloquence,” and “the firm support and unshakeable pillar of the Republic.”

Although insincere glorification of tyrants is certainly not unknown, Robespierre’s opponents were effectively acknowledging the deep division of opinion that would haunt debates for more than two hundred years. Was he just what the fledgling republic required in order to survive civil conflict and unrelenting war with virtually all of France’s neighbors, as his adherents believed? Was he a temporary aberration whose removal would set the republic back on course, as his gravediggers hoped? Or was he proof that violent revolution in the name of rights and social justice could only result in terror, violence, and ultimately authoritarianism, as some later commentators argued?

Advertisement

These questions are, as might be expected, especially troubling in France, which is why Marcel Gauchet subtitles his book “The Man Who Divides Us the Most,” “us” being the French. Yet the French are not the only ones concerned, since Gauchet’s preoccupation with Robespierre follows from his decades-long study of the philosophical underpinnings of modern democracy more generally. His work is not well known in the Anglophone world, though the controversies provoked by some of his opinions about current issues do echo more widely.

Although he began his career on the antitotalitarian left and still claims to be a socialist, Gauchet has been denounced in some French circles as reactionary, misogynistic, and homophobic. His 2004 essay on the potential negative consequences of increasing human control over procreation, rather than making do with what happens, prompted especially heated responses. Titled “The Child of Desire” and published in the journal he edited, Le Débat, known for its hard-line centrism, the essay seemed to bemoan the end of patriarchy, with its subjugation of women, by advancing the claim that “many children of desire will never know clearly who they are nor what they want,” because “they will remain forever dependent on this desire that brought them to life.”1

The accusations against Gauchet came to a head when he was asked to open the annual “rendezvous with history” in 2014. It is not easy for Americans to comprehend the popularity and influence of this festival, which is held in the Loire Valley town of Blois every October and draws some 40,000 avid participants to lectures, interviews, films, and panel discussions focused on recently published history books. An op-ed by a group of scholars in Le Monde in October 2014 insisted that Gauchet could hardly speak credibly about that year’s theme of “rebels,” since he encouraged conformism to “hierarchy, moral order, [and] tradition,” values brandished by the far right.2

Such characterizations of Gauchet’s positions are mistaken, I believe, but hardly surprising, given the stakes of the arguments he wants to make about modern democracy and the way that he often goes about making them. Modern democracies, he maintains, emerged as the religious foundations of collective existence crumbled; religion did not disappear, of course, but it no longer provided the crucial legitimation for the political and social order. Modern democracies therefore face the challenge of explaining to the citizenry what holds society together in the absence of any transcendental justification.

Gauchet is not convinced that human rights can fill the void, and his one overriding concern is that the modern emphasis on the individual and his or her rights will wear away the necessary foundations for a functioning social order. The fuzzy abstraction of his prose has left open the possibility, despite his disavowals in interviews, that he supports those who oppose the rights of women, gays, or minorities. The language in “The Child of Desire” is a case in point. He seems to criticize the right to choose whether or not to have a child, but at the end of the piece he makes clear that he has no wish to return to an authoritarian past; he does, however, want to consider what the costs of emancipation might be, both for society and for the individual.

Similarly, he wants to consider the difficulties faced by democracies, whose very existence depends on emancipation from traditional sources of authority. Democracy is inherently fragile because of the difficulty of explaining what holds people together in a secular world, and as a consequence, Gauchet maintains, it has a predisposition toward authoritarianism and even totalitarianism. Robespierre is therefore a perfect foil for Gauchet, because “he embodied the attempt to give liberty and equality their most complete expression” while personifying “the failure to make a viable system of government from these principles.” At a time when democracies face external and internal threats around the world, Robespierre is more relevant than ever.

Both the virtues and the defects of Gauchet’s approach are on view in Robespierre: The Man Who Divides Us Most, which is mercifully short in comparison with many of his other books. The defects are easily recounted: he largely ignores what has been written by others about his subject (whether democracy in general or Robespierre in particular) and glides past the nitty-gritty of everyday politics and social tensions in order to concentrate on the ways in which Robespierre fits into his larger arguments about democracy. This is not an unknown strategy in French writing about history and politics; the more polemical the essay, the less attention is paid to competing accounts or supporting documentation. (Gauchet provides virtually no footnotes.) In this spirit, he leaves aside any examination of Robespierre’s biography and considers only his writings and speeches.

Advertisement

Given the steady stream of biographies of Robespierre, many of them excellent, such an approach can be warranted only if it provides a fresh perspective. The virtue of Gauchet’s book is his laser-like focus on the one belief that shaped Robespierre’s constantly evolving opinions and actions: that government should reflect the will of the people, but particular interests, often involving conspiracies, stand in the way of the triumph of that general will. Viewing this prissy lawyer from northern France as a political philosopher would be a stretch, since the exigencies of the situation left him little time for writing essays, much less books or memoirs. Gauchet therefore aims at a middle ground where ideas meet events: “The innermost impulses that gave rise to Robespierre’s conduct are inseparable from a body of ideas that coalesced with them to form a system.”

Robespierre’s peculiar hold on his fellow deputies has long been one of the greatest mysteries of the entire French Revolution: How could this unprepossessing, previously unknown lawyer come to incarnate the Revolution in its most intense period? Gauchet is right to argue that Robespierre’s “manner of expression communicated the promise of the moment with a clearness and a precision that gradually elevated him to a preeminent place among his peers.” But he downplays the paradox involved, which was best captured by one of Robespierre’s erstwhile friends turned enemies, Marie-Jeanne Roland, who wrote while awaiting her execution in 1793:

His talent as an orator was worse than mediocre; his commonplace voice, his bad turns of phrase, his defective manner of speaking made his delivery extremely boring. But he defended principles with warmth and tenacity; he had the courage then [the king’s attempted flight in June 1791] to continue [to defend those principles] at a time when the defenders of the people were tremendously reduced in number.

In other words, though Robespierre’s views evolved over time, he never stopped portraying himself as the mouthpiece for the will of the people. He was not being inconsistent, therefore, when he held back at first from supporting the creation of a republic; he could imagine kings as “delegates” or “agents” of the people, even if Louis XVI could not. He proposed few laws yet soon gained a reputation for constantly reminding the deputies of the gap between “what the Revolution promised and what it had so far achieved.” Before long, however, as Gauchet shows, Robespierre’s “craving for popularity” deepened his identification with the general will. “The interest, the desire of the people is that of nature, of humanity; it is the general interest,” he argued in a speech in December 1790. He believed he knew the meaning and direction of that interest and that those who opposed the people (or him) represented only their own “ambition, pride, cupidity.”

Robespierre combined this unshakable confidence in the will of the people and his ability to interpret it with an obsessive dread of conspiracy, which he proclaimed from the first days of the Revolution. He did not invent the fear of treachery, but he certainly contributed to its credence. Alarm about secret plotting, sometimes delusional, sometimes not, would eventually justify ever more drastic measures of repression. It also fueled what Gauchet calls Robespierre’s “sacrificial narcissism,” his ostentatious self-abnegation combined with repeated references to himself as a martyr. These reached their zenith right before his fall, when he replied to those who accused him of seeking dictatorial powers, “Who am I, I who am accused? A slave of liberty, a living martyr of the Republic, as much the victim as the enemy of crime.”

Gauchet takes the dictator charge seriously but in the end argues that “his language was dictatorial, not his person.” Robespierre resembled a dictator in his ability to intimidate, but the intimidation did not include actual dictatorial powers. Gauchet’s way of putting this is characteristically abstract:

History provides us with no other example of someone who succeeded in objectively exercising a kind of dictatorship without subjectively putting himself in the position of a dictator, which is to say, as a practical matter, without providing himself with the means of actually exercising dictatorial power.

Because the deputies had been brought up reading Roman history and had the example of Oliver Cromwell even closer to hand, they worried incessantly about a dictator emerging from their midst. One was coming, but not until Robespierre had lain in his grave for more than five years.

Given Gauchet’s interest in the moral foundations of modern democracy, it is perhaps not surprising that he attributes Robespierre’s eventual downfall to his differences with other members of the Committee of Public Safety over religion. Robespierre viewed the campaign for de-Christianization in late 1793 with growing alarm and eventually denounced it. He then tried to inaugurate a Rousseau-style deistic alternative known as the Cult of the Supreme Being, whose festival he presided over in early June 1794.

Robespierre had in effect anticipated Gauchet’s own line of argument. Gauchet argues that Robespierre “ran up against the vicious circle to which any attempt to found a new regime on the basis of revolutionary principles is bound to lead.” In late 1792 Robespierre had concluded, “In order to form our political institutions, we would need to have the morals that one day they ought to give to us.” Gauchet calls this statement prophetic, but it comes right out of Rousseau’s Social Contract (1762). In his section on the need for a supreme legislator, Rousseau argued:

For a young people to be able to relish sound principles of political theory and follow the fundamental rules of statecraft, the effect would have to become the cause; the social spirit, which should be created by these institutions, would have to preside over their very foundation; and men would have to be before law what they should become by means of law.

Rousseau then concluded that this paradox explains why the fathers of nations “have recourse to divine intervention and credit the gods with their own wisdom.”

Although Gauchet emphasizes the differences between Robespierre and his enemies on the subject of religion, he cannot ignore the many other factors that contributed to Robespierre’s fall: the shock that followed the arrest, trial, and execution of Georges Danton and his followers, all of them staunch republicans, as traitors in April 1794; the spectacle of Robespierre as president of the National Convention presiding over his cherished Cult of the Supreme Being just two days before the infamous Law of Suspects deepened the dread among the deputies; and then, in a politically suicidal move, his withdrawal from public view for six weeks, only to reappear with vague threats against unnamed deputies. His enemies needed no further encouragement.

Gauchet’s Robespierre is a tragic figure because he brought an “ancient ideal of religious unity” to what would become modern problems. But he was not the only one who failed to establish a lasting republic in France in the 1790s; his successors failed, too. The only sustainable one on view, in the new United States of America, was very precarious, and it had the advantage of no aristocracy, no heritage of feudalism, supposedly unlimited land and resources, and, above all, distance from Europe. The American republicans barely managed to learn the lesson that is crucial to any democracy’s life expectancy: the alternation of power through an electoral process. Robespierre could not conceive it because he could not imagine that a political party was anything other than a particular interest, and therefore it was incompatible with the general will of the people. It is a lesson that is very hard to learn.