Fascination with actors shows no sign of abating. The public still, it seems, longs to know, as a journalist put it to Alec Guinness on his first visit to America, what makes them tick. (“I wasn’t aware that I was ticking,” Guinness replied.) What do actors wear, what do they eat, how often and in which positions do they have sex, what do they think? This insatiable curiosity perhaps betrays a residual sense of the uncanniness of these shape-shifters, these emblematic embodiers of what it is to be human. Of acting itself, though, there is less mention.

One of the challenges of writing about acting is that it constantly reinvents itself, always believing that its latest recension at last tells the truth about the human condition. After all, as the writer-director Hamlet tells his actors, “The purpose of playing, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold as ’twere the mirror up to nature, to show…the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.” The notion that there is some sort of immutable gold standard for truthful acting is deeply unreliable: cometh the hour, cometh the actor. When David Garrick, nimble and quick-witted, first leaped onto the scene with his dazzling realism and lightning changes of mood, the portly and impressively slow-moving James Quin, hitherto the darling of the pit, was heard to remark, “If the young fellow was right, he, and the rest of the players, had all been wrong.”

Garrick’s quicksilver transformations, so expressive of the Age of Enlightenment, were in turn supplanted by Edmund Kean’s dark and dangerous Romantic intensity. Each was initially admired for being more real than his predecessors; actors are never admired for being unnatural. In 1935 Laurence Olivier’s performances in Romeo and Juliet (he alternated the parts of Romeo and Mercutio) were regarded as ultrarealist; ten years later, in his Shakespeare films, it is clear that he was a somewhat stylized actor; on stage twenty years after that he was dismissed by many as monstrously mannered. His acting had not changed; the temper and taste of the times had. The shock of the new has a built-in decay, and it is in the nature of pioneers to believe that they have finally reached the promised land, the end of the rainbow.

One of the most notable instances of a shift in the vernacular of acting occurred in the early 1950s with the development of the Method, named and propagated by Lee Strasberg; it was held, rightly or wrongly, to have produced an entire generation of actors—among them Marlon Brando, James Dean, Paul Newman, and Marilyn Monroe—who, specializing in extreme emotional states, seemed to embody the alienation and rebellion of the 1950s and 1960s. The term “method acting” passed into the language, its terminology—“motivation,” “living the part”—partly mocked, partly viewed with awe.

A few decades earlier, informed theatergoers had become fascinated by something new stirring in the Russian theater, the mysterious so-called System of Konstantin Stanislavski; both the System and the Method were, in their day, intensely controversial with actors and audiences alike, as was the very idea of approaching acting systematically or methodically. Was acting not simply a gift, something you either had or didn’t have? Or else a craft, a matter of technique, a set of skills, vocal or physical, to be mastered? Noël Coward was much quoted: “You ask my advice about acting? Speak clearly, don’t bump into the furniture and if you must have motivation, think of your pay packet on Friday.”

The controversy, such as it was, has long since died away. The supposed influence of the Method came to a climax in the 1980s in the work of Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman, and Robert De Niro, and then, as it always will, acting started to change again: the form and pressure of the times required new heroes, new villains, new representative human beings. In The Method Isaac Butler traces the technique’s career: he is, he says, its biographer. The book arose out of his alarming experience as a drama student. Eager to truly live the part he was playing, he became so connected to his own dark emotions that he gave up acting altogether:

I hated the person I became during rehearsal as the nastiness of the character bled into my own personality, and I was not tough enough to manage the emotions my performance dug into. Since this was what I thought “real acting” demanded of me, I quit, and took up directing.

He was not, he says,

the first person for whom Stanislavski’s techniques had proved dangerous, nor would I be the last. That experience left me with many questions and few answers. Questions like: What did Stanislavski really believe and teach? Did the Method destroy American acting, or usher in its golden age? How does cultural change this massive even happen in the first place?

These questions themselves beg a number of other questions: Was the work Butler was doing in that studio a Stanislavskian technique? What is the connection between Stanislavski and the Method? And was the cultural change quite as momentous as he suggests? The Method is now a chapter in the history of acting, its status somewhat uncertain. “By the dawn of our current century,” writes Butler, “good acting could take any number of forms, and no one could claim a true way to attain it…. It can seem that the Method is dead, or perhaps a permanent invalid, wasting away.” In an age when people are disinclined to take up cudgels on behalf of one approach over another, it is rather bracing to read a book that traces the evolution of an acting theory whose partisans were so passionate, and that was as ferociously denounced as it was fanatically embraced.

Advertisement

Butler certainly takes it seriously, as we know by his subtitle: “How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act.” The idea that Lee Strasberg taught them how to act would certainly have come as a surprise to Greta Garbo, Charles Laughton, Mickey Rooney, Agnes Moorehead, Pierre Brasseur, Nikolai Cherkasov, Edith Evans, Laurence Olivier, or Anna Magnani, to select a tiny handful of twentieth-century acting titans, though one does see that the more factually precise “One of the Dominant Approaches to Acting in the United States of America for About Twenty-Five Years” is less likely to sell copies. On the whole, the book is much more sober than the subtitle threatens, though as he proceeds Butler seems increasingly impelled to justify it; toward the end, for example, we’re told that when Sanford Meisner died, “America entered a new era, one in which none of the original Method teachers remained.” I suspect that America took the news pretty calmly.

What Butler calls his biographical approach leads us gently by the hand:

To see what the Method is, we have to go back to that beginning. We have to go to a study in the Ekaterinoslav steppes where a playwright and teacher named Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, having reached a turning point in his career, decided to write a letter, one that would divert the stream of culture in a new direction, changing the course of art in the Western world.

It’s hard to think of anything that single-handedly changed the course of art in the Western world, though many developments opened up new possibilities; the Method was undoubtedly one of them. And it did all begin with a famous eighteen-hour meeting between Nemirovich-Danchenko and Konstantin Stanislavski, an encounter between two brilliant men with only one thing in common: a desire to transform the Russian theater of the late nineteenth century.

The severely stagestruck young Konstantin Alekseiev, the son of a wealthy textile merchant, spent far more time on the family estate in its private theater than in nearby Moscow. In 1877, at the age of fourteen, he was a founding member of the family’s amateur troupe, the Alekseiev Circle, whose standards—inspired by the great foreign actors and companies that had visited Moscow during the Lenten holidays—began to outstrip those of the commercial and state theaters. In 1888, only twenty-five, he created the Society of Art and Literature to bring together artists from every discipline.

Nemirovich, meanwhile, from a less wealthy background, wrote plays and taught acting at the state-run Moscow Maly Theater, where he struggled unavailingly against the muddle and mediocrity generated by the bureaucrats in charge of it. When he and Stanislavski (as Alekseiev had rechristened himself to avoid embarrassing his family) resolved to create a company, drawing up a radical set of rules for its conduct, they can scarcely have imagined the impact they would have.

The story of the Moscow Art Theatre, founded in 1898, and its profound influence on the American theater has often been told before, not least in Foster Hirsch’s A Method to Their Madness (1984), which covers the same territory as Butler’s book but less probingly. Butler offers copious (if not always entirely relevant) detail, sketching in the characters of the witty, feline, impatient Nemirovich and the courteous, emotional, often inarticulate Stanislavski and their long, tempestuous journey together, Nemirovich privileging plays over production, fidelity to the text over emotion, form—as they defined it—over content, while Stanislavski strove to access the actors’ creativity.

Despite the success of Stanislavski’s early productions and his own performances at the Moscow Art Theatre, he was frustrated by his and his fellow actors’ failure to rise above the merely proficient. After a decade he took a sabbatical in Finland, pondering the work of the great actors he admired—the Italians Eleanora Duse and Tommaso Salvini, for example—in order to tease out the conditions for truly creative acting. His answers came slowly, over some years, only ceasing with his death in 1938, and from the beginning they proved divisive.

Advertisement

Butler manfully strides into the whirlpool of misapprehension in which Stanislavski studies exist, due partly to Stanislavski’s unmethodical approach—his work was essentially exploratory and in constant evolution—and to the vagaries of translation. For instance, he divided up levels of acting, starting with the lowest form, to which he attached the word ремесло—remeslo, which Butler renders as “hackwork.” But the Russian word has no pejorative connotation, being more properly translated as solid, craftsmanlike work—not exalted, but not contemptible either. Stanislavski was trying to identify the steps involved in achieving the sustained inspiration he discerned in great actors (among whose number he did not count himself). When he presented his initial findings to his colleagues, they were unimpressed, as was Nemirovich, with whom his relationship was growing ever more acrimonious.

To a large extent it can be said that Stanislavski devised his System, as he called it, to counter his own perceived weaknesses: self-consciousness, anxiety (he spoke of “the black and terrible hole of the proscenium arch”—not a feeling most actors share), lack of spontaneity. His obsession with the inner lives of characters is demonstrably a by-product of his very erratic relationship to language, in life and onstage. Nemirovich noted that he had great difficulty remembering text, which he habitually paraphrased; in ordinary conversation he frequently got words in a tangle. His System unsurprisingly focused on physical action and on the character’s subconscious. Constantly confronting his own limitations, groping his way forward, reading widely in fields where he had no expertise—psychology, philosophy, neurology, religion—he probed ever deeper into the heart of acting. As Jean Benedetti remarks at the beginning of his invaluable Stanislavski: An Introduction (1982), “Had Stanislavski been a ‘natural,’ an actor of instinctive genius, there would be no System.”

He took the company’s rejection of his findings very badly. After 1911, though he continued to act in the repertory he had built up over the Moscow Art Theatre’s first decade—he was its star actor—he ceased to initiate new productions for the main company, founding (and personally paying for) a studio where he could experiment with the younger actors and demanding “the freedom to fail.” He never stopped evolving his System, forming strong relationships with successive generations of actors, many of whom, like Vsevolod Meyerhold, Yevgeny Vakhtangov, and Alexander Taïrov, became deeply influential in their own right. Remarkably, news of these explorations, and especially of the System, spread to Europe and then to America. By the early 1920s the company, having endured a world war and two revolutions, was forced to tour if it was to survive. This it did, with a reluctant Stanislavski at its head, mounting seasons in Europe and eventually the United States, where its impact was immense.

The repertory Stanislavski and his colleagues were performing consisted entirely of the company’s early work, and the troupe was made up of actors who had rejected the System. But it galvanized a politically conscious generation of American actors and directors with a vision of the theater as challenging and many-layered, to which they scornfully compared what they held to be the formulaic offerings available on Broadway and in regional theaters. While the company was still playing in New York, Richard Boleslavsky, a Polish actor and director, once a member of the Moscow Art Theatre and a protégé of Stanislavski’s, gave lectures on his System, after which he was offered the directorship of a new school, the American Laboratory Theatre. Among its earliest students were three intense young Americans: the would-be director Lee Strasberg, the critic Harold Clurman, and the actress Stella Adler, all of whom had been transfixed by the Russians’ visit; Clurman had already seen and been overwhelmed by the work in Paris.

The trio, determined to form a company of their own, recruited a passionately idealistic group of actors, writers, and teachers they called the Group Theatre. Butler vividly recounts the challenge for the disparate company of evolving a common vision of plays, of staging, and above all of acting. From the beginning Strasberg, abrasive, autocratic, and deficient in normal social skills, created tension with his uncompromising insistence on emotion as the essential element of acting. This was his contribution to the theory. Stanislavski (and Boleslavsky following him) believed that the actor must have ready access to his or her emotions in order to understand those of the character, but Strasberg claimed that the actor’s personal emotional experience, accessed by means of intensive engagement with his or her memories, was the sole route to truthful acting, and that this personal emotion should be superimposed on the character’s—should be substituted for it. He devised exercises to enable the actors to engage with their unexplored inner emotional lives.

A fault line immediately opened up within the Group Theatre. “What is this hocus-pocus?” demanded the distinguished Broadway veteran Morris Carnovsky. But Strasberg would not be gainsaid, and as Butler recounts, he was “prone to rages, screaming at actors when they didn’t do what he wanted.” His old friend Clurman described his “almost sadistic fury when he was balked.” On a trip to Moscow he revisited the work of the Art Theatre and was appalled by it, claiming that the Group Theatre was now a better company. It “went beyond Stanislavski’s verisimilitude,” he said, and boasted that the Group’s productions “had more intensity than the Moscow Art Theatre’s at any time.”

Meanwhile, in the summer of 1934, Adler, who had been bridling under Strasberg’s autocratic yoke, sought out Stanislavski, then touring in Paris, and told him that his System, as parlayed by Strasberg, was destroying her pleasure in acting. To her intense relief, Stanislavski told her that the Group—under Strasberg’s tutelage—had gotten his System wrong. What was crucial to him was not emotion, it was what he then called “the problem,” and later redefined as the objective—the character’s need or want. “He did not use, and did not think people should use, emotional memory exercises,” writes Butler.

Problems, action, the given circumstances, and imagination were the keys to the system. You got to emotion through them, not the other way around. “If your director…says, please feel [first] and then you will be able to play, tell him ‘when I know how to swim then I will go into the water.’ Can one swim without going into the water? One cannot feel and then do the problem—first act the problem for the physical action and then you will be able to feel.”

When Adler relayed this to the actors of the Group Theatre, there was rejoicing. Strasberg angrily denied that he was overemphasizing emotion. Anyway, he declared that he did not teach the Stanislavski System, he taught the Strasberg Method. Disgusted, Adler became a teacher herself, focusing on action rather than emotion, insisting on the autonomy of the character as separate from the actor. “Where Strasberg used the self as the raw material for a performance,” writes Butler, “Stella wanted to transform and transcend the self. Your job as an actor was to enlarge your own soul to meet—or become worthy of—the character you were to play.” Strasberg, by contrast, was concerned with digging ever deeper into the actor’s self, as poor Butler discovered as a drama student.

Adler, a superb actress, was the scion of actors in the Yiddish Theater: her father was the great Jacob Adler, renowned as the Yiddish King Lear, her brother Luther a star in his own right; she had made her first appearance onstage at the age of three. Strasberg’s early career as an actor was brief and undistinguished, though he was immersed in theater history; his hero was the English director and theorist Edward Gordon Craig. In his memoir, A Dream of Passion (1987), Strasberg defends Craig’s provocative essay “The Actor and the Übermarionette,” insisting that it did not undervalue actors but simply argued that the actor “must possess the precision and skill that the marionette is capable of.” Elsewhere, as quoted in the distinguished theater scholar Helen Krich Chinoy’s posthumously published The Group Theatre (2013), he stated that an actor’s primary duty is to become “an IDEAL machine for transmission of emotion”; character interpretation, he said, is best left to the director. Strasberg, notes Chinoy, discovered in Craig’s pages “not only the art of theater but also the artist of the theater—the director,” an interesting paradox, given the divergence between Strasberg’s dream of obedient actors and the wayward behavior of practitioners of the Method.

Strasberg does not emerge attractively from Butler’s pages. Within the Group Theatre he was known, not affectionately, as General Lee, drilling and regimenting his actors. When the actress Beany Barker, directed by him to behave in a rigidly prescriptive way, momentarily forgot a move he had given her, Strasberg harangued her unrelentingly until she broke down in tears, at which point her fellow actor, the usually demure Ruth Nelson, said, “Now I’m going to kill him.” As she hurled herself at him, Strasberg fled the theater and the production.

Butler reports that Clifford Odets, later the Group Theatre’s star playwright but then an actor, wrote in his diary that Strasberg’s obsessive “emphasis on emotion grew out of the lack of affection in his upbringing.” Odets might have written less sympathetically had he known that after a run-through of his first play, Waiting for Lefty, which established the reputation of the Group and opened the way for a generation of politically conscious playwrights, Strasberg, who had sat in on it “like a remote father observing the games of his recalcitrant children,” said to Clurman, “Let ’em fall and break their necks.”

The play did the opposite: it made the Group Theatre. Before Lefty had even opened, the directors of the company—Clurman, Strasberg, and business manager Cheryl Crawford—determined to close the season early. The actors rebelled, saying that Odets was writing another play, Awake and Sing!, with excellent parts for many of them, but the directors refused to approve it for performance. When Odets protested that the play was almost completed, Strasberg said, “You don’t understand, Clifford. We don’t like your play.” Elia Kazan, a stage manager on the production, claimed that this remark destroyed Strasberg’s standing in the Group forever; its members went ahead in defiance of the directors and programmed the play immediately after Lefty, ushering in a new chapter in the American theater—without Strasberg.

Clurman stepped into the breach and took over the play’s direction. When he faltered in organizing the traffic onstage, Kazan, the watchful young apprentice from Constantinople who seemed to have an instinctive grasp of the craft, stepped in. In a very short time, he would prove himself to be preternaturally gifted at harnessing the positive elements of the Method while quietly discarding what was not useful. Butler is inclined to attribute Kazan’s directorial approach to Stanislavskian-Strasbergian theory, but in reality it consisted of simple instinct, the sort of thing any competent director would do. “The first thing you should do with an actor,” wrote Kazan, “is take him to dinner…. When you know what an actor has, you can reach in and arouse it, right?” Directing the child actress Peggy Ann Garner in his debut as a film director, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), he asked her about her own father, who was at the front, subtly hinting that he might not return from the war. She wept all day. “Her outburst of pain and fear was essential to her performance,” Kazan said. “It was the real thing. I was proud of that scene, of its absolute truth.” This is textbook directorial psychology, albeit of a somewhat brutal variety, especially considering the age of the performer.

Within a few years, Kazan had established himself as the hottest director on Broadway. He publicly identified himself with the work of the Group Theatre and the Method that had evolved there, while pointedly refraining from associating himself with Strasberg. In 1947, alongside Cheryl Crawford and the acting teacher Robert Lewis, he founded the Actors Studio in New York. It had no plan to produce plays: no one who worked there would be paid, and admission would be free. The membership would be dedicated to “continuous improvement and experimentation.”

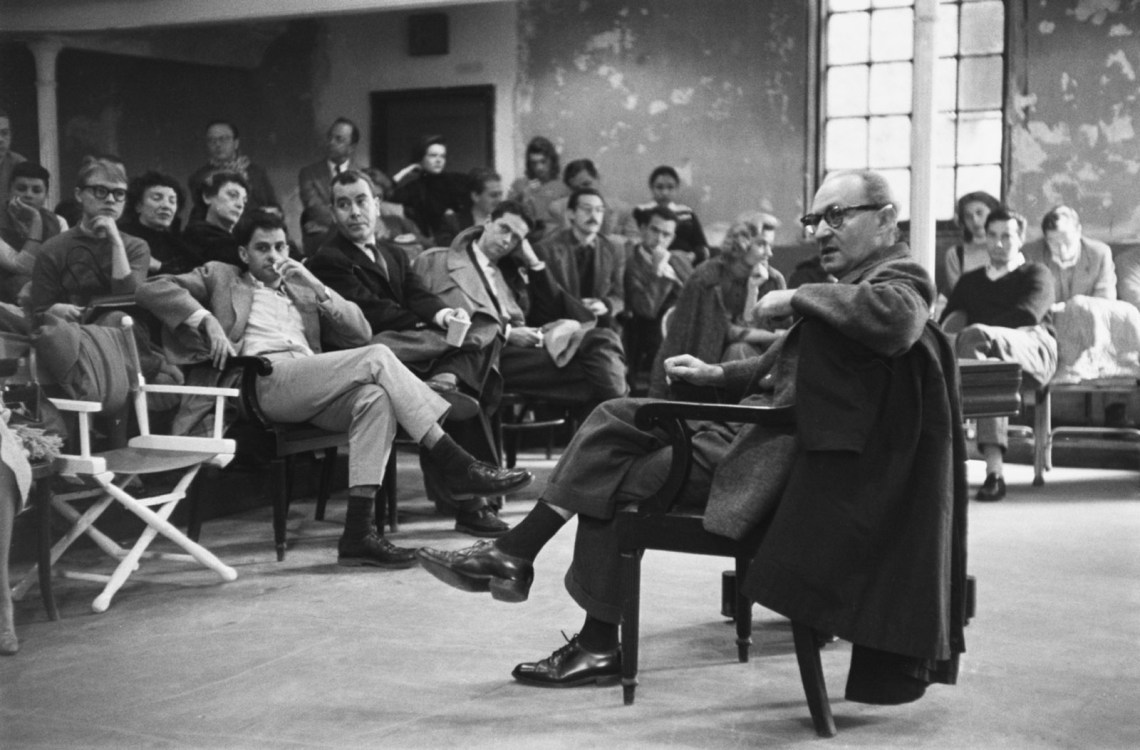

What was on offer was not a formal training but simply classes—just two a week—in which all the other essential skills of an actor, vocal and physical, were assumed to have already been acquired. At the Actors Studio, a couple of students per session offered up exercises, performed in front of other students, and were assessed by the teacher. It was essentially a form of instruction in how to perform the exercises, how to derive the most from them; its inherent limitation was that it was particular to those exercises and to the students’ engagement with them. From the beginning it was very popular, not least because of Kazan’s fame; The New York Times reported that “a fledgling organization called the Actors Studio is quietly nurturing the most luxuriant crop of young performers Broadway has reaped in many seasons.”

Among the remarkable productions Kazan mounted in the 1940s was Tennessee Williams’s masterpiece, A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), its antihero Stanley Kowalski brought to alarming, unforgettable life by the twenty-three-year-old Marlon Brando. Butler devotes many pages to the production and to a detailed account of Brando’s career and life, noting, among other interesting information, whom he was dating and when. It is here that the book begins to become somewhat unclear of purpose. Brando studied at the Dramatic Workshop of the New School, whose principal was Erwin Piscator, Brecht’s collaborator and a pioneer of epic theater—as far from the Method as can be conceived. Among his teachers was Adler, who had publicly declared herself the sworn enemy of Strasberg’s Method. Throughout his career, Brando pointedly dissociated himself from Strasberg, stressing his indebtedness to Adler. He wrote in his autobiography:

After I had some success, Lee Strasberg tried to take credit for teaching me how to act. He never taught me anything. He would have claimed credit for the sun and the moon if he believed he could get away with it. He was an ambitious, selfish man who exploited the people who attended the Actors Studio and tried to project himself as an acting oracle and guru. Some people worshipped him, but I never knew why. I sometimes went to the Actors Studio on Saturday mornings because Elia Kazan was teaching, and there were usually a lot of good-looking girls, but Strasberg never taught me acting. Stella [Adler] did—and later Kazan.

Regardless, near the end of his book Butler writes that as Don Corleone in The Godfather (1972) Brando passed “the Method torch to a new generation.” Increasingly, almost every actor of any merit mentioned in the book becomes de facto a Method actor; he even recruits the president of the United States:

There was something of the Method style to John F. Kennedy, and as the Method had spent the prior decade establishing its dominance on America’s stages and screens, this was key to his appeal.

One might have thought that Kennedy owed rather more to the Alan Ladd school of acting, and no one ever accused him of being a Method actor.

The hyperbolic grandiosity of the book’s subtitle comes home to roost in ever wilder and more absurd statements. Perfectly straightforward approaches to acting are claimed as somehow indebted to the Method: Butler quotes Faye Dunaway as confiding to The New York Times in 1974 that “you draw on personal experiences. You use parts of yourself,” as if every actor who ever lived hadn’t done that. The director Arthur Penn is quoted as saying that Warren Beatty—who studied with Adler and Robert Lewis, both hostile to Strasberg and the Method—was helped in his performance in Bonnie and Clyde (1967) by adopting a limp. Every actor’s desperate last resort has now been absorbed into the Method. Al Pacino, publicly a great fan of Strasberg, used none of his exercises. Instead, says Butler, “he became known in the industry for his ability to ‘absorb’ people, watching them intensely and then somehow, mysteriously, taking on their essence and embodying it”—i.e., he was an example of what actors have alarmingly been from the dawn of time: shape-shifters stealing people’s souls. That too, it appears from Butler’s pages, is somehow the domain of the Method.

The last quarter of the book traces Strasberg and his Method’s erratic if ultimately triumphant trajectory, from his surprising assumption of the directorship of the Actors Studio in 1951, after Kazan’s departure when he and Lewis fell out, to his failed attempt to create an American national theater and the humiliating debacle of the visit of his production of The Three Sisters to London for the World Theatre Season in 1965. It also unflinchingly covers the unsavory episode of his relationship with Marilyn Monroe: the actress, in frail mental health, submitted to Strasberg’s probing of her distress, which can only have exacerbated it. She became emotionally dependent on him, leaving him and his family all her personal belongings as well as 75 percent of her residuary estate, including control of the use of her image. They made millions of dollars from it; the Studio, meanwhile, largely thanks to the Monroe association, became the most famous acting workshop in the world.

Strasberg’s occasional writing, including A Dream of Passion and his measured introduction to Diderot’s Paradox of the Actor, reveals a scholarly and temperate alter ego, but his primary persona, on display at the Actors Studio, was as a bully and a scourge. He “was a damn near despotic and frightening figure,” Penn reported. “There was a gory ten years where Lee ruled with a capricious iron fist.” Butler goes on:

But all of this also meant that, as Martin Balsam, put it, “he was impossible to please.” If you focused on emotion, he’d say you were neglecting action; if you were focused on action, he’d zero in on your feelings.

It could be argued that Strasberg was trying to push his students to surrender their rational minds to their instinctive selves, which is a legitimate part of any training. But at the Studio this was all there was. “We were all eager to please and our egos were so fragile,” Balsam said. “It was murder.”

In the summer of 1962 the foxlike Kazan, loyal only to himself and his talent, and about to initiate the new Repertory Theater of Lincoln Center, took to The New York Times to denounce the limitations of Strasberg’s teaching:

Too much of the “Method” talk about actors today is a defense against new artistic challenges, rationalizations for their own ineptitudes. We have a swarm of actors who are ideologues and theorists. There have been days when I felt I would swap them all for a gang of wandering players, who could dance and sing, and who were, above all else, entertainers….

We will need…an actor who has gone beyond the training of his psychological instrument and has really set about training his theatrical instrument.

It was, however, Kazan who crashed and burned, walking away from Lincoln Center in 1965, while the Studio, on television and in films, if not notably on stage, produced actors who were, it seemed, uniquely in tune with the times. By the late 1970s, however, there was a sense that things were moving on. The Times sent a reporter to talk to the two rival self-appointed inheritors of Stanislavski’s work:

“Lee Strasberg?” Stella Adler says. “I think what he does is sick. Too many of his students have come to me ready for an institution.”

“Stella Adler?” Lee Strasberg says. “What about her? There’s no comparison between the people who have come out of my school and the people who have come out of her school.”

On hearing of Strasberg’s death in 1982, Adler said, “Good riddance. He will finally stop destroying actors.” Then, at the first acting class she taught after the news broke, she called for a moment of silence. When it ended, she said, “It will take the theater decades to recover from the damage that Lee Strasberg inflicted on actors.” A decade later she too was dead, by which time the Method, and indeed Stanislavski’s work, had been subsumed into a more general approach to teaching acting. Butler gamely tries to suggest that the legacy of the Method is still to be found: “The Method—still taught, and misunderstood, and championed, and maligned—is both here and not, hovering over us, ever present and invisible all at once.” But he is compelled to acknowledge that what he calls the greatest film of the 1980s, Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, left both Stanislavski and Strasberg far behind.

Butler is good-hearted, passionate even, in his desire to celebrate what he rightly takes to be a significant chapter in the history of twentieth-century acting. He stumbles, however, when he attempts to elucidate Stanislavski’s theories, writing incomprehensibly, for example, about the core idea of objectives:

When Hamlet says “To be or not to be,” he must have an object. Perhaps it is himself, perhaps it is God, or the mind, or the entire state of Denmark. Any of these could be the object of an action.

No actor could make head or tail of this.

But these flaws are as nothing by comparison with an enormous act of omission: Butler implies that the Method was the only game in town, that before the Stanislavskian-Strasbergian revolution, American acting was stuck in a torpid, conventional, complacent, incurious rut. “Kazan,” he writes, “wanted actors who had ‘the ability to understand not only the lines but the reasons for those lines.’” What on earth makes Butler think that every actor worth his or her salt was not concerned with exactly that issue—that actors had not, indeed, from time immemorial, been concerned with it? From the mid-nineteenth century, with the great nationwide expansion of theater made possible by the railroad, there had arisen within the profession a huge demand for a proper and rigorous training, a demand answered by the rise of drama academies and individual teachers, among them such luminaries as Minnie Maddern Fiske and Eva Le Gallienne. The American Academy of Dramatic Arts was founded in 1884—fully twenty years before the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts in London—by Franklin Sargent; from 1923 until his death in 1952, it was run by the remarkable pedagogue Charles Jehlinger. Among its distinguished graduates were Spencer Tracy, Agnes Moorehead, Kirk Douglas, Edward G. Robinson, Grace Kelly, Lauren Bacall, Anne Bancroft, John Cassavetes, Gena Rowlands, Robert Redford, and M. Emmet Walsh.

The American Academy’s training was (and is) systematic, rigorous, and dedicated above all to stimulating the actor’s creative response to character, based on deep immersion in the play and what it contains. “Yield to the character” was Jehlinger’s watchword, “and let it take control of affairs.” This element, strikingly absent from the work of Strasberg, is and has ever been, from the fourth century BCE, the actor’s special sphere. Most of us become actors precisely in order to create character—to escape from ourselves, to some extent, but principally because we have been fascinated by people, their quirks, their qualities, their mysterious workings. We are artists in character—portrait painters in three living dimensions.

In her illuminating Modern Acting (2016), Cynthia Baron describes the immensely effective and widely followed approach to acting from which her book takes its name, which strives to facilitate the actor’s creative involvement; its teachers, many of whom taught in conservatories, were, after the coming of sound, indispensable to the Hollywood studios, whose directors were not always equipped to help the actors with creating character. Sophie Rosenstein’s Modern Acting: A Manual (1936) insists:

Acting a role does not mean learning lines, cues, stage business, and set responses. It means creating the inner life of the character delineated by the playwright. This includes thoughts, sensations, perceptions, and emotions in fluid state, in constant fluctuation.

A talented actor is one who can express in terms of himself the inner life of another individual.

This is no prescription for hackwork, no formulaic, generalized approach, but it does presuppose a degree of autonomy in the actor, far from Strasberg’s insistence that an actor’s primary duty is to become “an IDEAL machine for transmission of emotion,” with character interpretation left to the director.

These are now old battles. The world of actor training is again under fire—in Britain at any rate—from all quarters. Until two or three years ago, young people from all parts of the globe flocked to submit to the rigorous regimens of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, the Guildhall School, the Royal Central School, or the London Academy of Music and Drama. Then the principal of this last-named institution was succeeded by a well-known theater director who immediately announced fundamental changes. More than half the staff left or were made redundant; the very basis of the teaching was challenged, the plays on which the students worked were to undergo severe reappraisal, they would be closely consulted on what it was that they’d like to learn, and the work of Stanislavski—dead, white, and male, as he inarguably was—would forthwith be banished from the curriculum. After a year, this new principal resigned amid deep student dissatisfaction, but the turmoil continues, there and in all the other London academies. No doubt acting is about to reinvent itself again.

It is hard not to believe that at some point the new dispensation will turn a blind eye to Stanislavski’s whiteness, maleness, and deadness and find a place for his unrivaled exploration of the possibilities of this most expressive art. The American director Joshua Logan visited Moscow in 1931 and was astonished at the variety of Stanislavski’s work. The first production he saw was of The Marriage of Figaro:

It was done with a racy, intense, farcical spirit which we had not associated with Stanislavski. It was as broad comedy playing and directing as anything we had ever seen….

It was our first shock at the realization…that he was first and foremost the interpreter of the author’s play.

Each of the subsequent productions they saw was in an entirely different mode. When Logan left, he asked Stanislavski about his system. “Create your own method,” was the reply. “Don’t depend slavishly on mine. Make up something that will work for you! But keep breaking traditions, I beg you.” His legacy, properly understood, is endlessly rich and stimulating. Whether in the future anyone will wish to pay attention to the Method of the single-issue fanatic Lee Strasberg is, however, to be doubted.